As part of our ongoing investigation into contemporary practices, we visited Noldor, Accra’s first independent artist residency. Located in what was formerly a pharmaceutical factory in Labadi, the residency provides resources — including but not limited to working space, materials, exhibition opportunities, and a network — to emerging and mid-career artists from Africa and the African diaspora, with a particular focus on Ghanaian artists through a uniquely tailored yearlong fellowship. Flash Art dispatched Blaykyi Kenyah, an artist and writer, to have a conversation with Noldor’s founder, Joseph Awuah Darko, himself an artist and art dealer, as well as Kenza Hamdi, managing director, on the goals of the residency and the general state and future of the Ghanaian art scene.

Blaykyi Kenyah: Let’s start, perhaps, with the personal, Joseph. I know you have lived many lives, and in a recent iteration you created abstract art. Can you share a bit about that, and how it ties to the founding of the residency?

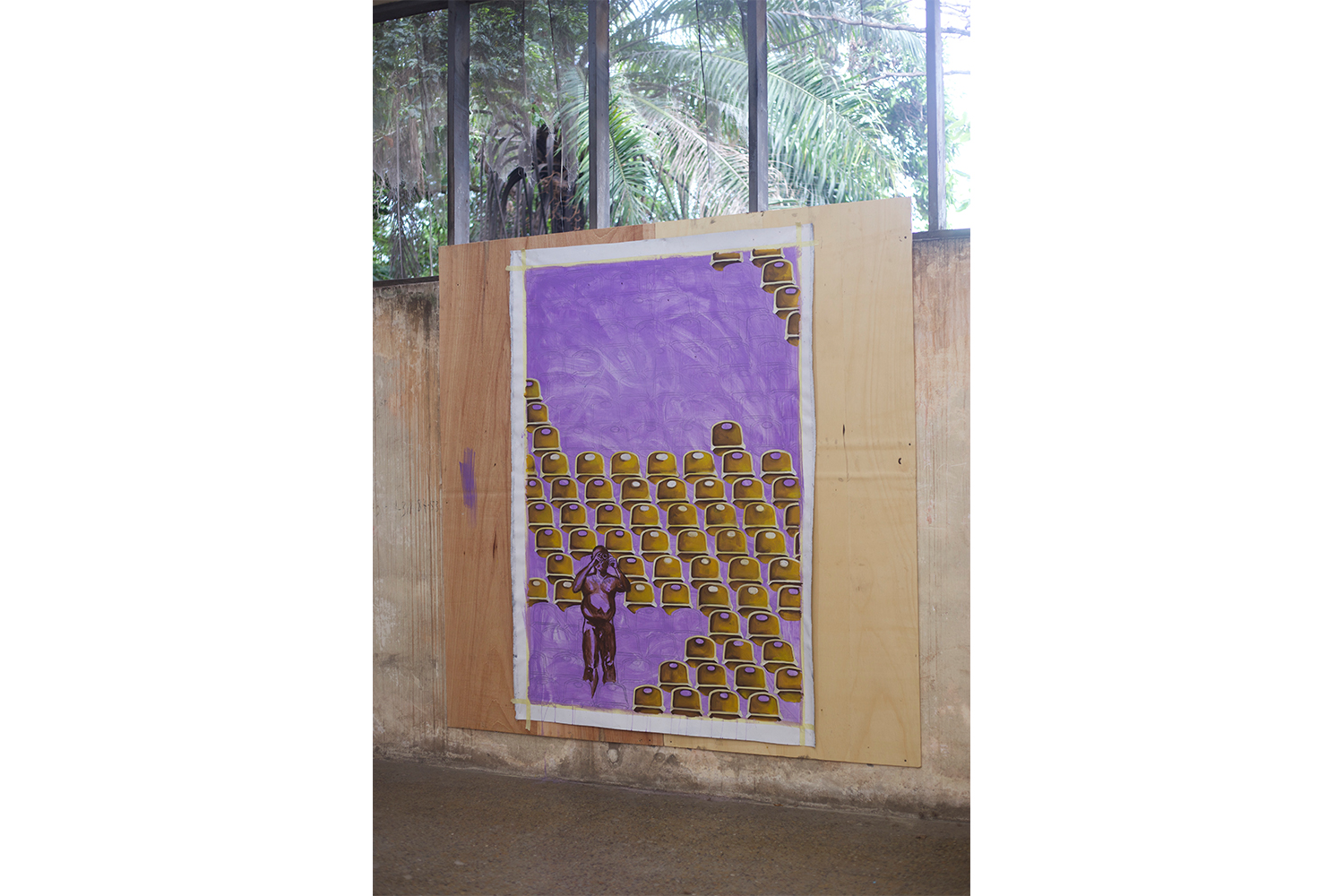

Joseph Awuah Darko: Yes, my practice — and this was three, four years ago — was centered around a Duchampian upcycling of “refuse” from what has been dubbed the world’s largest e-waste dumpsite, Agbogbloshie, right here in Accra. In 2019, some of the aesthetic products of this exploration were solo-exhibited at Gallery 1957 in Accra. I currently identify as a creative multi-hyphenate: I have made music, made art, put together shows, worked with other artists in many capacities. This helps me with empathizing with artists, although I would not call myself one right now.

BK: Empathizing with artists?

JAD: Understanding the dynamics of artistic processes, and how varied and straining they can be. I think one major effect of my practice on this residency is the priority given to nurturing per se, on creating the best environment that allows for creative proliferation, as opposed to focusing singularly on products as a final destination. And so I work with amazing people like Kenza Hamdi, and the other seven people on our staff, to achieve a healthy balance, especially since we work so often with emerging artists who also feel pressured to put themselves out there. As Kenza will attest, it is not easy work.

Kenza Hamdi: Care, as a praxis, has been really important to us. Care, not only in recognizing that art needs to be tended to, like a plant does — it needs a balance of space and attention — but also care in the sense of intentionality. This is a first in so many domains for us. For Joseph, this is the first time steering a ship this large and complex; for our artists, many have never been artists-in-residence in Accra, mostly because this is the first of its kind, an unaffiliated residency, which is itself growing and so needs much care at this crucial stage. For me, this is the first time I’ve actively engaged with this side of the behemoth that is the art ecosystem.

BK: Can you speak some more to how this collaboration came to be?

KH: We had worked together on earlier enterprises when I was a model in Joseph’s video projects. We both ended up in Ghana during the earlier stages of the pandemic, and Joseph invited me to work, actually invited me to interview. It is quite gratifying to know that though there is a lot of trust between us, that trust is also built on a fair assessment of our competence.

BK: I am interested in framing this residency as an intervention in Ghana’s cultural milieu, an experiment of sorts. There is a glaring lack of art institutions in this city that are not tied in some form to art-as-commerce, and this is not at all a takedown of these spaces. The Nubuke Foundation on the public front, and commercial spaces like Marwan Zakhem’s Gallery 1957, Adora Mba’s ADA\Contemporary, and many others, are expanding and reframing the ways citizens of Accra interact with art. All of this is to say, while the scene here is nascent in a formal sense, it has a decades-long rich history. What, in your estimation, is the critical intervention of Noldor at this particular point in space-time?

JAD: One of the many lives I have lived is as a collector, and I have been fortunate to befriend many of the artists whose practices I have been keen to support: Gideon Appah, Serge Attukwei Clottey, Ablade Glover. You realize very quickly that there is, even at this point, a certain predisposition to value product over process, which stems, of course, from a colonial legacy of professionalism as a means to enter the middle class: think doctors, lawyers, teachers… certainly not artists! So this returns again to nurture. Noldor is coming in to tend the plants that give us the fruits we are all very grateful for.

BK: I’m sure the name Noldor is in reference to a cultural touchpoint I’m missing.

KH: Lord of the Rings! Joseph here is quite a fan of Tolkien’s world, and so the name, which refers to a kindred that made seeing-stones, was bouncing in his head. We started work and the name stuck as a nod both to worldbuilding — a primary call of artists anywhere — as well as to play and constructive experimentation.

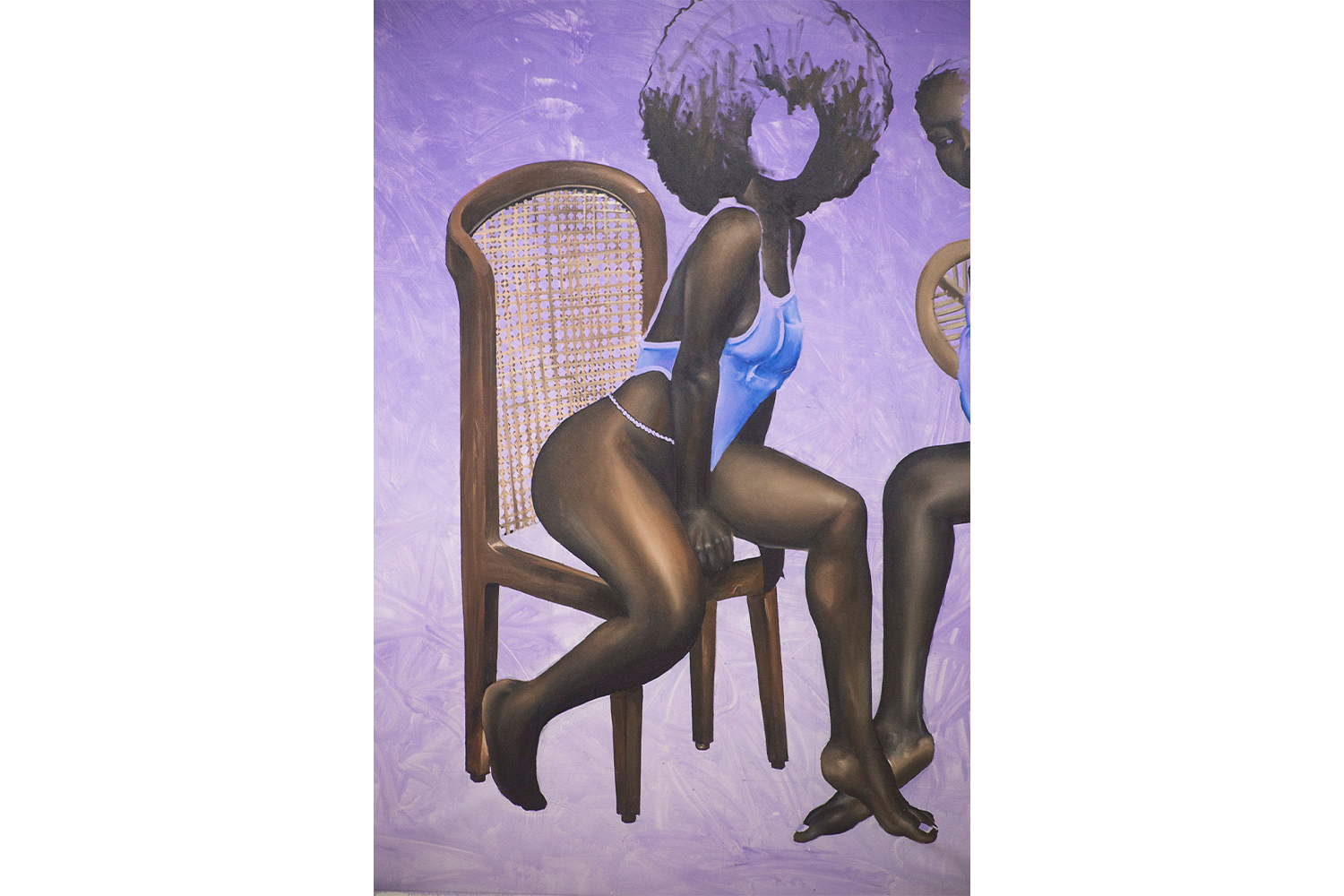

BK: A quick history of Noldor, the residency, not the Tolkienism: you had your first resident last year in October, Emmanuel Taku, whose stay formally ended with a very interesting show on your premises in December. You quickly followed by expanding the residency to include two fellowship programs: a senior fellowship for more established artists, this year hosting Gideon Appah, and junior fellowship with two fellows this year, Joshua Oheneba-Takyi, and Abigail Aba Otoo. You are also planning on hosting an artist-in-residence later this year. Fervor, urgency, I do not know what you may call it, but this rate of expansion requires some learning to cycle while you’re peddling. As crafters of this new program, how have you responded to the cultural ecology within which this residency finds itself?

KH: Flexibility is the name of the game. Ghanaian culture is quite polychronic, and so we have had to engage with it, with all its pluses and minuses. The residency provides its residents and fellows with access to huge studio spaces, all materials requested, and a generous monthly stipend. We also try to incorporate rest as an essential part of care, with getaways, including a built-in week long retreat where a therapist comes in to work with residents. Recognizing that artists have lives outside of their practice is a part of enabling them to have sustainable practices. In that sense, this residency is not an escape from the “real world”; it disrupts it only to find a new stable equilibrium, immediately for the artists and hopefully for the art scene writ large.

JAD: It is definitely not a one-size-fits-all model, across different dimensions, be it time or the artists’ needs. Abigail, for example, is getting her doctorate in pharmacy, and so we’ve had to accommodate that. We do like the structure we have built out, and we think we will always have residents and fellows. When we started out, Emmanuel [Taku] was a sort of proof-of-concept, that this could work within, as you put it, this cultural ecology. We were, frankly and humbly, incredibly surprised at the success of this pilot, and so it made a lot sense to expand it. On a related note, part of creating sustainable practices is being a commercially aware residency. Artists invest a lot of time and money into their practices, and so we try to facilitate opportunities for artists to benefit off their investments, as we did with Emmanuel’s sold-out April show in Knokke, Belgium, with MARUANI MERCER. As an art dealer, this is within my forte, so I’m glad to leverage that skill here — giving them contract support, legal support, and just building a network, which, mind you, is an important aspect of this residency. We are really fortunate to find ourselves in Labadi, which happens to be uniquely vibrant within Accra as a hub for artistic production: Serge Attukwei Clottey’s studio is here, so is Omanye Aba, the Artist Alliance studio and exhibition space. We are fortunate to have artists coming in and interacting with the residents and fellows.

BK: Thank you for bringing up the issue of art and commerce. How does Noldor balance this emphasis you have repeatedly hammered on, on the need for nurture, with a white-hot market for contemporary African artists, a market that is ready to consume whatever these artists produce? Is there a tension there at all to begin with? Does the residency engage with it in any sense?

JAD: This need for a healthy balance exists for any artist, resident or not, between sustaining yourself economically and deepening your practice. It is easy to slip into a self-righteous puritanism. Being commercially aware is being a realist, and recognizing that whatever the artists produce will be entering what you called a white-hot, booming, heavy quotes “art market.” Ours is to provide support: legal, emotional care. Even here too, nurture reveals its necessity. I would make the distinction then between awareness and a focus. The residency is a space to think about art, to make art, without worrying about what comes after.

BK: Why did you place “art market” in heavy quotation marks?

JAD: I think addressing the overcommodification of art sometimes does tend to drain me. I try to dissociate my love of art from the art market, because although they exist in tandem, they are very far apart. It’s so speculative, and you do get this frenzied booming obsession. I’m much more interested in the artists’ practices, and in supporting them, and that’s where Noldor is focused,

KH: There is this awareness that we are, to extend the metaphor, watering a plant whose fruits will be enjoyed by many, and collected and sold, quite literally, to many. This is something that I know Joseph has grappled with, because the metaphorical image reveals the prima facie oddity of this. However, when one considers the goals of the residency, and the importance of artists to any society, even beyond their artistic products per se, one appreciates the value of residencies such as Noldor.