The balancing act between Apollonian thought and Dionysian urges has a long lineage in art and literature, not least in the writings of Nietzsche, who theorized that the internal tension between reason and chaos lay behind most artistic creation. It has certainly provided fertile ground for the work of artist Jill Mulleady, whose striking oil paintings filled with contorted figures conjure up troubling mental imagery in a bid to exorcise deep inner drives.

Born in Montevideo, Uruguay, in 1980, Mulleady studied drama and formed an independent theater troupe in Paris before turning her hand to art. After graduating with an MFA from Chelsea College of Arts in London in 2009, she relocated to Los Angeles, where she has lived and worked since 2013. Aside from a period between 2011 and 2014, when she created abstract painted environments, her oeuvre since 2004 has almost uniformly consisted of expressive and unsettling figurative oil paintings.

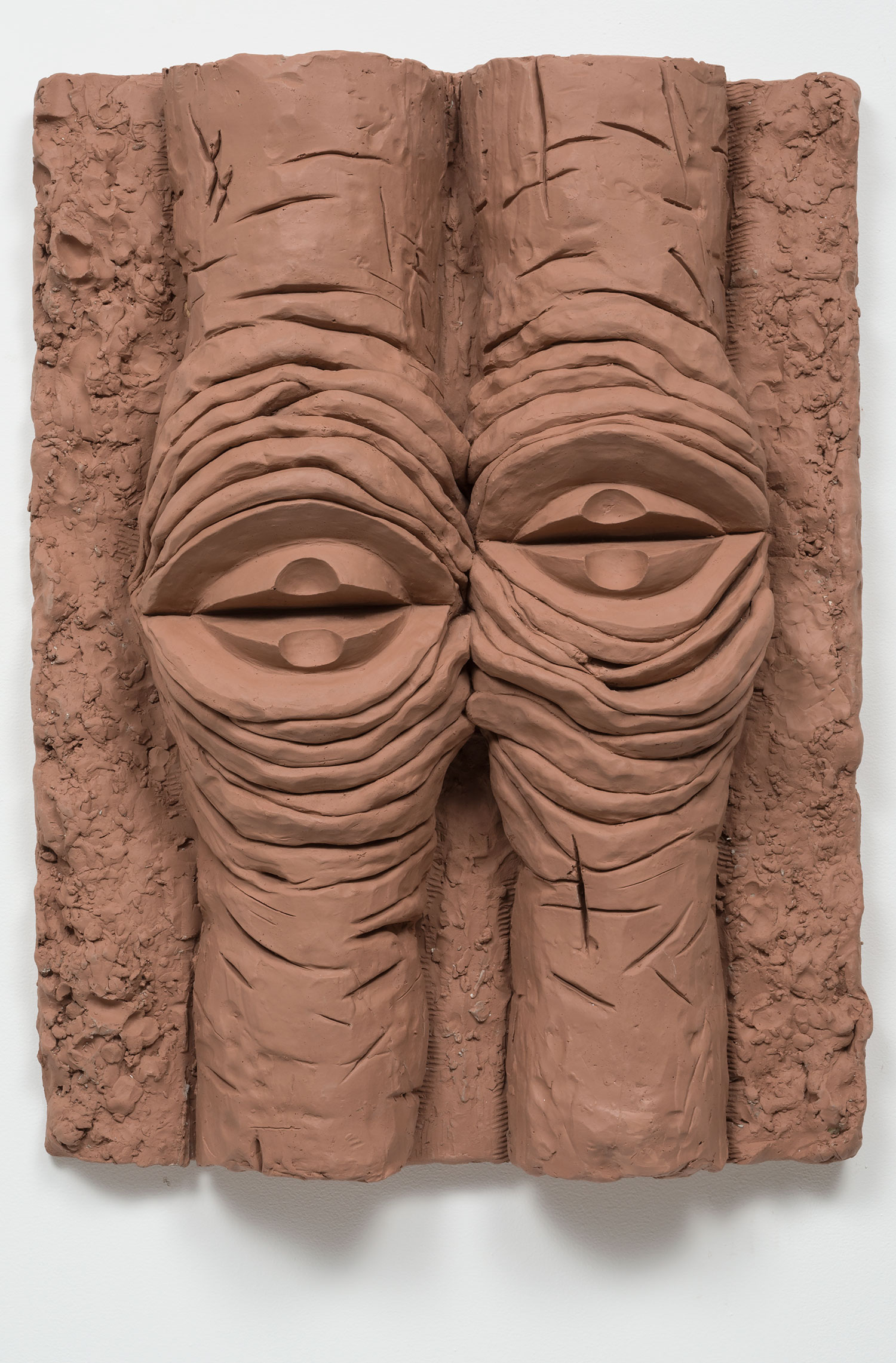

Mulleady’s aptly named exhibition “Fear,” at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Naples, positively brimmed with paintings suggestive of deep-rooted anxieties. A hellhound that could just as easily have been found in a medieval illuminated manuscript dominates Riot II (2015). This winged and horned figure with a gaping, toothy mouth and peculiarly human arms is almost upstaged by a pair of devilish shadows and a grinning witch. In Riot I (2015), a crimson-colored monster with a piglike snout reaches up to grasp a branch. Decked with a rounded cap, which apes the distinctive shape of a Roman helmet, the figure is set before a hand brandishing a sickle, evoking the blood-soaked mise-en-scène of the gladiatorial arena.

In Origines cultuelles et mythiques d’un certain comportement des dames romaines (2015), named after a book by Pierre Klossowski, Mulleady depicts a stocky black imp squatting over a woman in what looks to be a forced act of fellatio. At the other end, her prone figure is violated by a monstrous creature, dripping with saliva and other bodily fluids. The nightmarish characters in this Dionysian psychosexual drama directly echo the fantastical creations of artists like Henry Fuseli and William Blake. It is precisely in that echo that the intellectual, or Apollonian, impulse in her work becomes most evident — through a studied invocation of classical symbols and art-historical references, culled into a distinctive set of surreal and brutal imagery.

Poets, writers and artists from the past also appear frequently in Mulleady’s work. A figure closely resembling the French dramatist Antonin Artaud, for one, featured prominently in “This Mortal Coil,” Mulleady’s recent exhibition at Freedman Fitzpatrick in Los Angeles and the artist’s first solo show in her adopted home. A member of the Surrealist group in Paris, Artaud was best known for his Theatre of Cruelty, which, with its violent themes of torture, destruction and death, attempted to provoke the repressed feelings of polite bourgeois society and incite the audience to act according to their instincts. Mulleady clearly has a continued interest in such boundary breaking, evidenced in her subjects and titles. With “This Mortal Coil,” she ventured her own conceptual provocation in the form of a false floor installed in the gallery space. Forcing the viewer to go “onstage” in order to closely see the paintings, the artist directly implicated the visitor in the complex relationships between the works, activating us from viewer to player and inviting us to strut and fret our hour upon the stage.

Artaud’s doppelgänger appeared in two nearly identical paintings installed at the heart of the show, The Green Room I (2017) and The Green Room II (2017), with only barely perceptible differences between them, such as the angle of the figure’s left hand. With ghastly lime-tinged skin and a harlequin-like contrapposto, he looks away from a spilled drink. The doubling effect of The Green Room works was echoed in A Sun for the Sleepers I–III (2017), a series of three woodcuts in which the same character appeared in triplicate, though in these works he is flipped to appear in reverse. Such mirroring is often experienced as deeply uncanny, something Freud attributed to the notion of the soul being distinct from the physical body, which suggested an aspect of one’s self that cannot be contained. The greenish hue of Mulleady’s green man recalls popular representations of that most famous uncontrollable self — Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

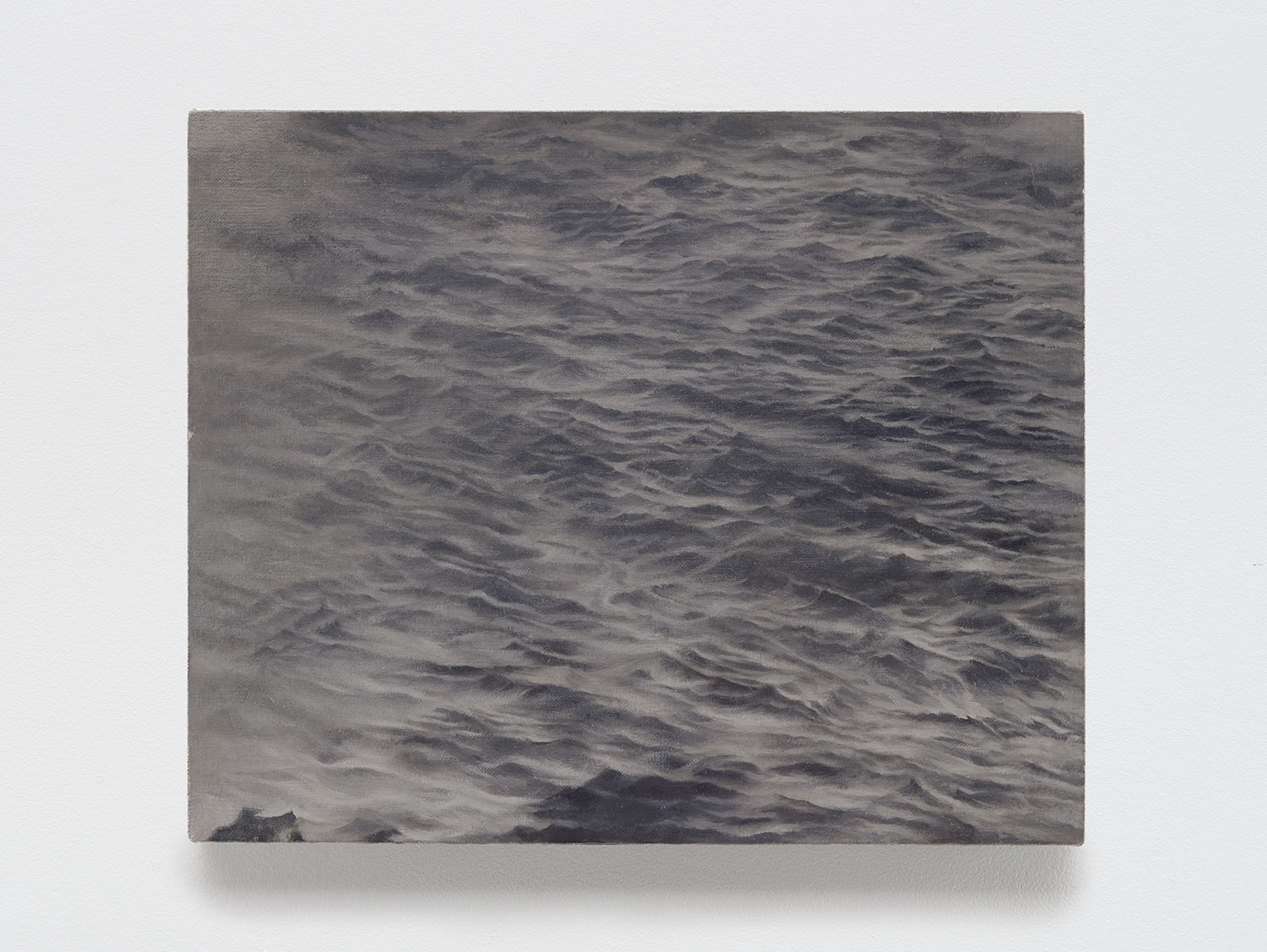

“This Mortal Coil” comprised ten oil paintings, mostly set in bars and enveloped in a chartreuse miasma suggestive of the psychic fog of absinthe. This so-called “green fairy” famously recurred throughout the paintings of Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec, among others, and Mulleady produces echoes of other familiar Montmartre denizens, for instance the expectant bartender of A thousand natural shocks (2016), who appears like a reincarnation of the dolorous protagonist from Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1892). Most of Mulleady’s recent works are hallucinatory tableaux, made up of disparate figures, animals and objects. A cheetah sits attentively at a half-empty bar in Made in the Shade (2017), while a figure styled after Martin Kippenberger slumps over the counter. The cat sits with its back to the viewer, transfixed by a television displaying a CCTV feed of the parking lot outside Freedman Fitzpatrick. The combination of shamanic artist and spirit animal, in a setting copied from a mid-1990s photograph of Kippenberger’s visit to Dawson City in Canada, suggests the loose associative logic of altered states, whether experienced during intoxication or sleep. That Mulleady is intrigued by the subconscious is further confirmed by the exhibition text for “Fear,” which mentions the Duke of Zhou who, according to Chinese legend, appeared in dreams to portend momentous events. Like Freud, Mulleady sees dreams and drunkenness as the last refuge of our latent desires in a repressive social order, a permissive realm in which one’s Dionysian drives can take fullest expression.

It’s not all chaos, however, for Apollo does intervene on occasion. Mulleady has always taken care to offset her discombobulating visions of violence or narcotic stupor with scenes of utter normality. In works like Beating the System (2015) and Spray la vie (2016) — respectively a neatly stacked dishwasher and a kitchen sink full of glasses, cups and bowls — she renders her subjects with absolute clarity, with a greater emphasis on naturalistic detail than in her evocative, more loosely painted large canvases. These works suggest that the restless nights filled with uneasy dreams will always take place amid the mundane reality of everyday life, the inference being that such phantasms are as workaday and banal as the washing-up.

Yet recently the strangeness of her work has taken on a more urgent tone. In a painting whose title offers a blunt summation of our current political moment, Kleptocracy (2017), Joan of Arc can be seen slaying a repulsive tongue-like being, while in the background a crouching woman, adopting the angled pose of Picasso’s brutally powerful Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), is intended as a reference to Melania Trump. On the wall there hangs a picture of an emaciated polar bear treading an ever-shrinking ice cap, a direct reference to the present administration’s suspicion of climate change and casual disregard for environmental protection. Filled with monsters and corruption, Kleptocracy presents a frightening picture of the shape our world is taking. As the walking, talking id of America, embodying its grasping at wealth, status and power, Melania’s husband provides rich fodder for the Dionysian imagination. In a political era defined by the alt-right web, fake news and so-called “alternative facts,” we are living in an echo chamber of unprecedented proportions, where even the dominant discourse has recognized the poststructuralist edict that there is no essential connection between the signified and its signifier.

Mulleady’s work opens up the broader question of how we are served by representations of violence and horror. For Klossowski, the best means of comprehending one’s darkest impulses was to reproduce them in the form of a simulacrum, or copy. Klossowski, who spent years training for the priesthood in a Catholic seminary before losing his vocation, was fascinated by sadomasochistic imaginings. But does the simulacrum offer an edifying spectacle or does it merely entrench violence and abasement? Is it truly exorcism, or is it reinforcement? Does it need to be accompanied by a trigger warning? Of course, to represent something — say, for instance, the fear and loathing of contemporary life under Bannon’s administration — is not to be the thing itself. The simulacrum captures the essence of an obsession and, in recreating it, must be both fearful and tantalizing. For Klossowski this dualism meant the pursuit of transgression in order to access the sacred, though his contemporary Georges Bataille had a rather less mystical interpretation. In his 1949 essay “The Cruel Practice of Art,” Bataille compared the motivation of the Surrealist painter to the Aztecs and their human sacrifices, in that both shared a desire to see “the hidden movement of the human heart,” for “the painting of horror reveals the opening onto all possibility.”

Rather than shying away from one’s demons, it is more constructive for artists like Mulleady to tame them using words or images. It is true that, once formed, such simulacra possess a life of their own in the world — no longer merely the product of an individual imagination, but one that is revealed to the eyes of spectators and understood in myriad ways. While losing control of the interpretation of one’s simulacra may be frightening, ultimately it can create a community of response through multiple articulations, where others troubled by such notions can choose to give voice to their fears. It is by sharing these imaginings that we can tackle that which truly threatens us. In this way, Mulleady invites us into a terrifying world, but one that must be faced head-on and without flinching.