For more than a decade, Neïl Beloufa has produced a vast array of films and installations that propel viewers into dizzying image economies in which reality and fiction collide and systems of authority are enacted and upended. The French-Algerian artist bricolages unruly image-worlds from the archival detritus of culture and politics — referencing everything from Hollywood melodrama to the theatrics of reality TV, news anchors, and bombastic politicians. Although Beloufa appropriates his sources indiscriminately, their reconfiguration across films and installations divests their media forms of their productive functions and exploits the totemic power of the image in digital culture to unexpected and vertiginous ends.

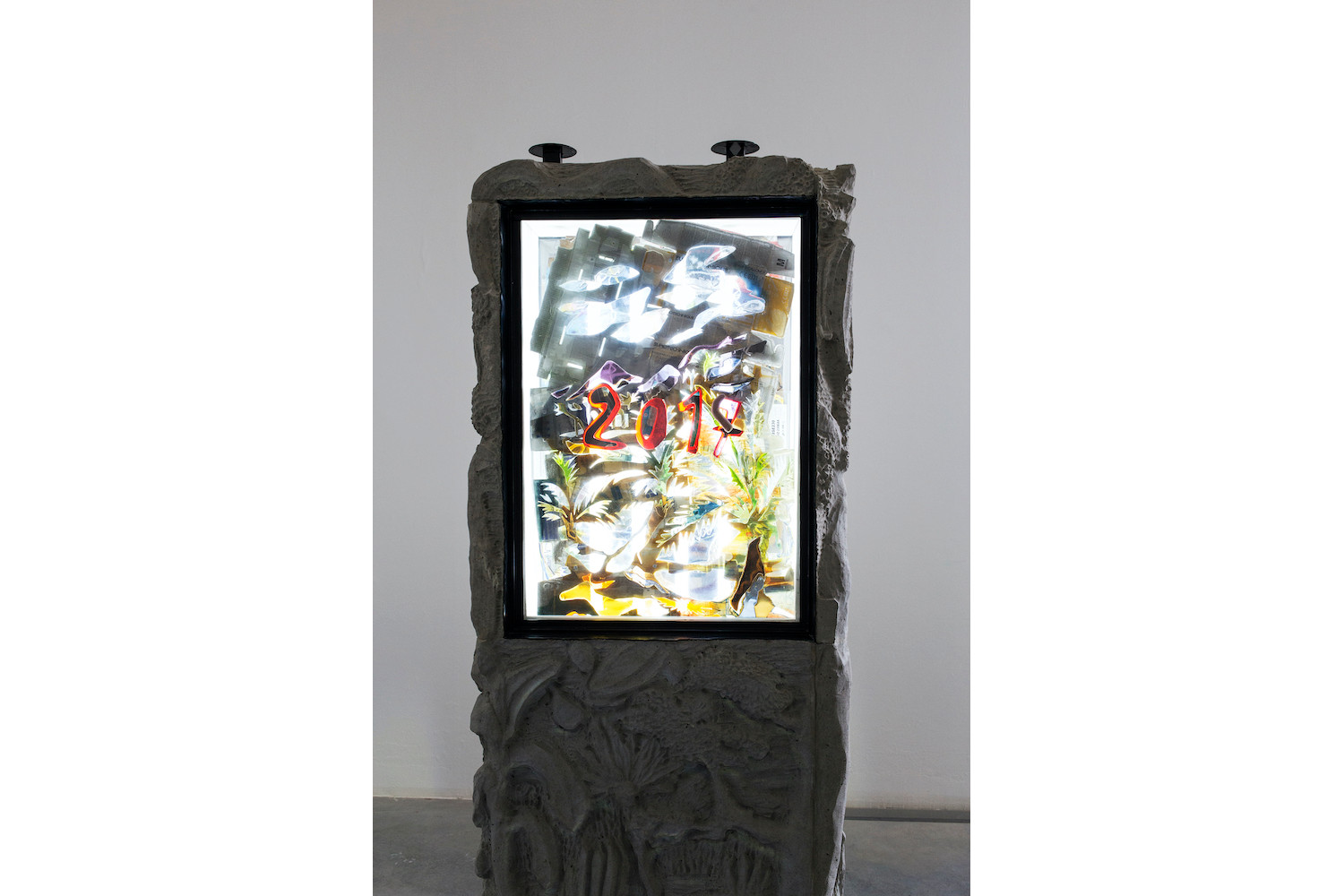

In www.screen-talk.com (2020), his newest collaborative project made with the production company Bad Manner’s, Beloufa revisits Screen Talk, a miniseries that the artist made in 2014. Based on a screenplay co-written with the cartoonist Léo Maret and a script co-written with the artist Jory Rabinovitz, the series was shot with nonprofessional actors at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity in Canada. On www.screen-talk.com, the five episodes of Screen Talkare embedded within the bewildering website’s glitchy chromatic labyrinth, whose interactive aesthetic evokes something between the zany experiments of early net art and annoying game apps like Candy Crush.

The uncanny resonances between Screen Talk and the present prompted the artist to return to this former material. Beloufa’s construction of a novel virtual environment in which the former videos are embedded, recontextualized, and newly encountered reflects his repeated self-designation as less of a sculptor or filmmaker and more of an “editor,” selecting and arranging media to reconstruct critical, and at times chaotic, relationships between artworks and viewers. Screen Talk imagines a world gripped by the throes of a fictional pandemic: scientists race to identify symptoms and find a cure, a crazy family goes even crazier in quarantine, relationships break down under the weighted distance of digital intimacy, and paranoia mounts under the invisibility of a sweeping illness satirically named “hallucination.” While Beloufa and Bad Manner’s explicitly specify the fictional status of Screen Talk — envisioned six years before the outbreak of COVID-19 — upon opening the website and at the start of each video, the actuality of the ongoing pandemic is nonetheless eerily analogous to the dystopian present that Beloufa envisioned.

The experimental format of www.screen-talk.com compounds two central problematics that run throughout Beloufa’s works. The proleptic or anticipatory relationship between Screen Talk’s epidemiological dark comedy and the present pandemic underscores Beloufa’s preoccupation with the stakes of imagining the future from a standpoint internal to or within the aftermath of catastrophe. Moreover, Screen Talk is less concerned with the specificities of disease than with how the experience of a pandemic is biopolitically governed by social networks and technologies of power. Through their totalizing reliance on technologies like Skype, the characters in Screen Talk are relayed to each other and to viewers within immaterial economies as cyber-surveilled moving images. We encounter not people but instead their aesthetic avatars of networked data, as in our contemporary moment of Zoom zombification. The theorist Paul B. Preciado has called this era “pharmacopornographic,” and Beloufa satirically underscores the precarious conditions in which it produces subjectivity.1 www.screen-talk.com is “pharmaco-” in its staging of biopolitical anxieties, and “pornographic” insofar as it models the quantification of the affects and desires of our intimate lives within contemporary cognitive and emotional capitalism.

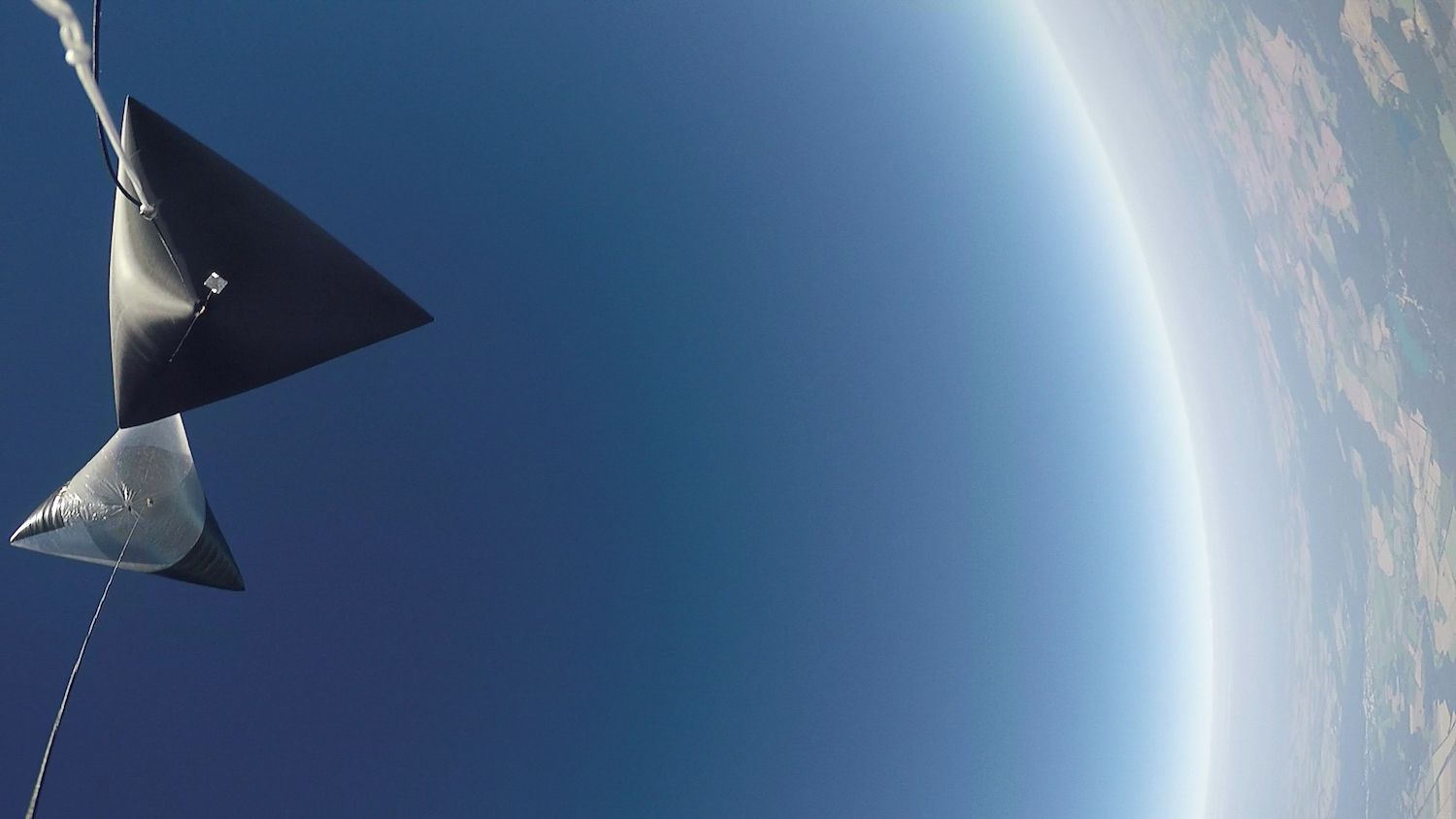

The formal elements of www.screen-talk.com reflect the catastrophic circumstances in which it emerged. Upon opening the website and clicking through the warning of its fictional status, viewers encounter an infographic that announces, “A pandemic is wreaking pandemonium worldwide and pharma companies scramble to patent a cure,” before being prompted to choose an avatar for entering the website’s maze-like structure. At the top, a “fake news” bar mocks the televisual convention of running headlines with parodic phrases like “With stocks plummeting and traditional values providing no answers, a large portion of brokers and bankers have turned to astrology, warning that Scorpio season will be the most deceptive and kinkiest time the DOW has seen in decades and should not be trusted.” This conjunction of financialized deception with astrological fetishism demonstrates a statement in Screen Talk’s first episode, that “superstition, ignorance plus fear” contribute to the crisis of the disease. The quotidian is meanwhile cast into paranoid doubt. Framed by bottles of hand sanitizer and smartwater, a scientist announces with deadpan disinterestedness, “How interesting, coughing might be a symptom of sickness.” Like the absurdist experience of our present pandemic, every mundane cough is a potential infection and thus every person an automatic enemy.

www.screen-talk.com illustrates the quandaries of artistic production and exhibition during a pandemic, providing an alternative to the content-driven digital clamor of art institutions floundering for relevance under the directives of “social distancing” (and some faltering once again amid Black Lives Matter uprisings worldwide, through representational activism — lest we forget the black squares — and half-hearted proclamations against racism without actual imperatives for structural change). Instead of filling the art world’s void, the anonymous co-authorship and autonomous ecosystem of www.screen-talk.com sidesteps digital exhibitionary platforms that compound the aura of artists and institutions online. In doing so, it gestures toward future possibilities of appropriating technology and distributing authorship to produce art-adjacent things that might reach wider audiences.

In a public Zoom conversation between Beloufa, artist Meriem Bennani, and curator Myriam Ben Salah, Beloufa cited Bennani and Orian Barki’s 2 Lizards videos (2020) as an inspiration for developing www.screen-talk.com, initially “as a joke to start a conversation.” 2 Lizards is an ongoing series of videos accessible on Bennani’s Instagram account, where the two animated lizard protagonists experience the onset of the COVID-19 in New York in real time. 2 Lizardscompellingly portrays urban life under the pandemic’s state of exception through a distinctive approach to media. Recurrent throughout Bennani’s practice, animation and animal avatars playfully establish critical distance from charged political, often postcolonial, contexts. Made to be viewed solely on Instagram, 2 Lizards exists as an accessible noninstitutionalized experiment within a post-cinematic environment. Whereas Bennani and Barki exploit the given limits of a digital app, Beloufa’s co-produced website exists as a self-sufficient system. Both offer valuable critical strategies for reimagining art production within a post-catastrophic present.

Despite motifs of predictive futures that recur throughout his work, Beloufa did not augur COVID-19 six years earlier in Screen Talk. The history of the AIDS crisis and the recent SARS, H1N1, and Ebola outbreaks provide precedents for a world under viral threat. Yet in conceiving present and future catastrophes from prior crises, Beloufa sheds light on their attendant rhetorical fiascos — like philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s inflammatory claim that COVID-19 is just “a normal flu, not much different than those that affect us every year.”2

Just as in our pandemic present, www.screen-talk.com is rife with the fraught rhetorical status of information. The viewer must navigate through a distracting web of interactive games and mini-quizzes, only to view the episodes of Screen Talkout of order. While these disruptions defamiliarize the series’ narrative trajectory, their nonlinear dimension resists the hegemonic temporalities of “breaking” news cycles and false claims of returning to normalcy in the pandemic’s aftermath, “where everything goes back to happily ever after,” as Screen Talk’s principal scientist Dr. Martin contends.

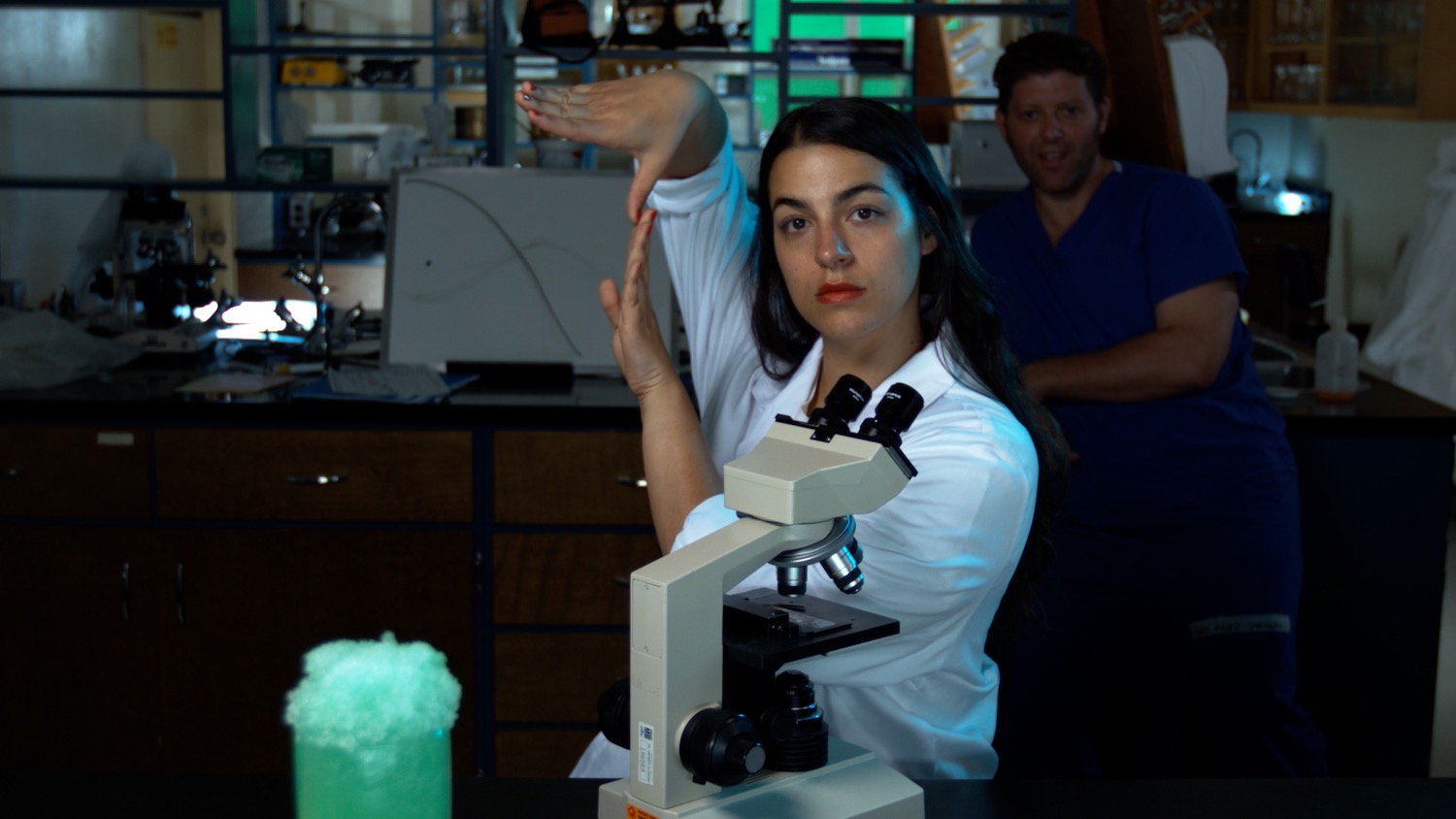

Along with the “fake news” bar, one quiz asks viewers to look up an answer on Wikipedia, as if encouraging misinformation. The videos, moreover, are saturated with the scientists’ farcical “indubitable conclusions,” nonsensical claims like “there is a three-in-one chance that the epidemic will happen worldwide” and a “sixty-percent chance people won’t be ninety-nine-percent OK.” These mindless and comical assertions verge into misogyny when the scientist Jim (who is “more interested in female anatomy than pathology”) objectifies Dr. Suki, Dr. Martin’s collaborator and not-so-secret lover. Stunned by her attractive image on a conference call, Jim sneers, in a pun on “screengrab”: “I’d grab more than a screen.” It’s almost as if Beloufa predicted Trump’s degrading misogyny too.

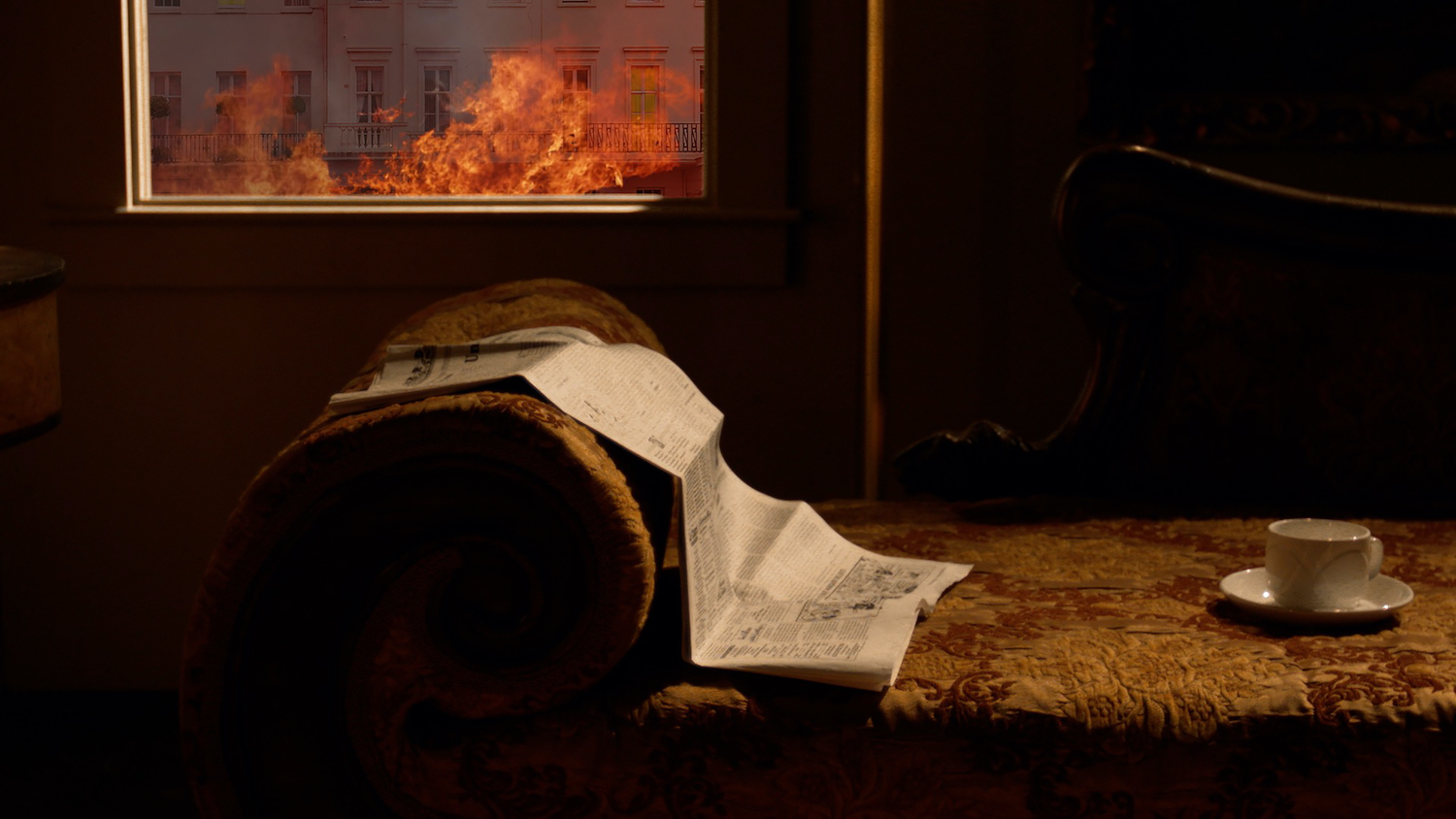

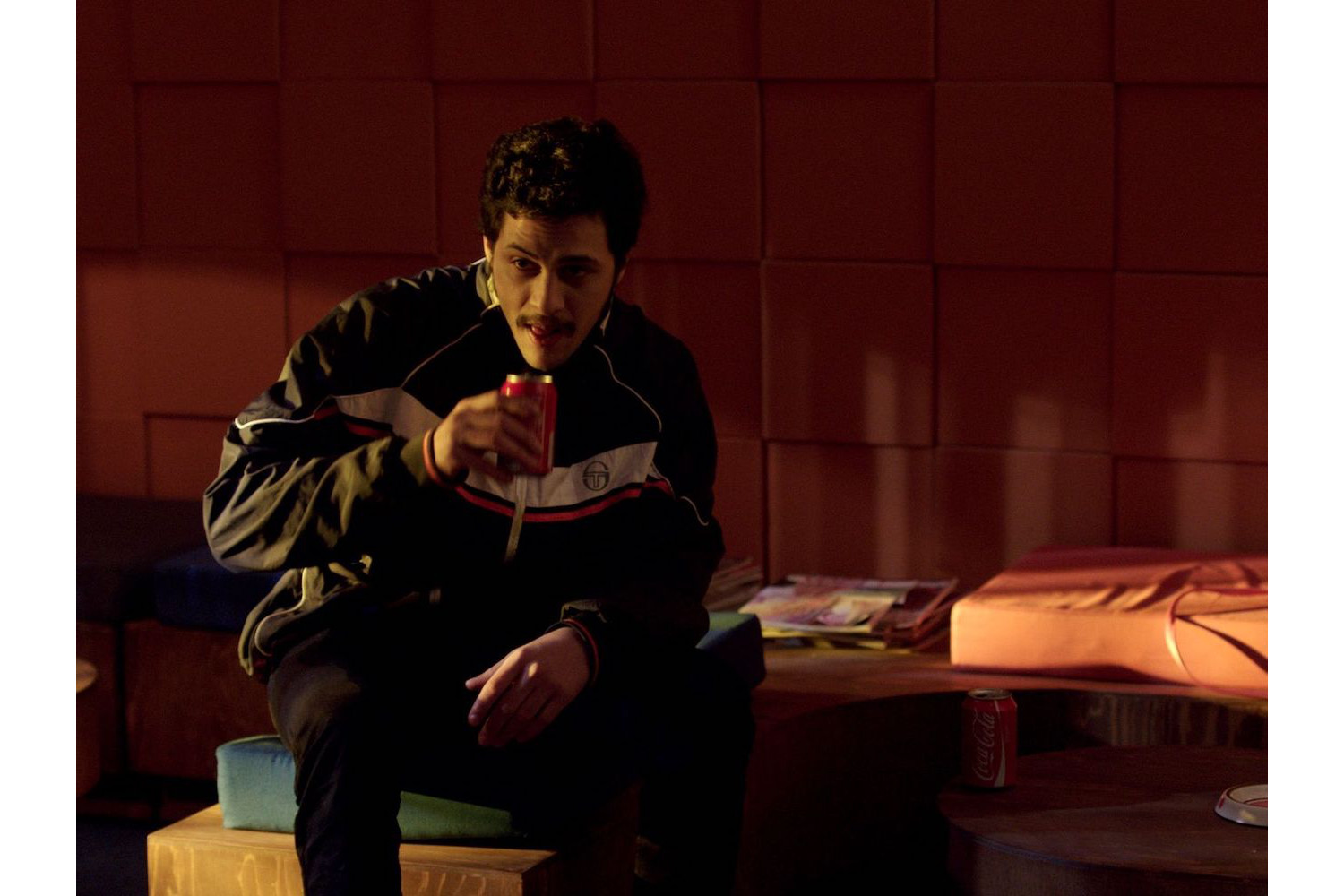

The political instrumentalization of truth and lies in www.screen-talk.com follows from Beloufa’s earlier experiments with the slipperiness of language during catastrophes. In his feature film Occidental (2017), an unidentifiable duo (gay? Italian? Muslim?) provoke racialized and sexualized suspicion in a hotel and are subject to surveillance. The film’s explosive identitarian rhetoric is a microcosm for the protests taking place outside the hotel, a reference to the 2005 banlieue riots and 2015 attacks in Paris. In his film World Domination (2012), amateur actors pretend to be presidents. Seated around a circular table, they utter impassioned performative declarations of war that expose how rhetoric justifies racism and violence regardless of political orientation. In the face of an abstract contagion like that of Screen Talk, one fake president in World Domination even announces the necessity of “deploying armed forces to stop the plague.”

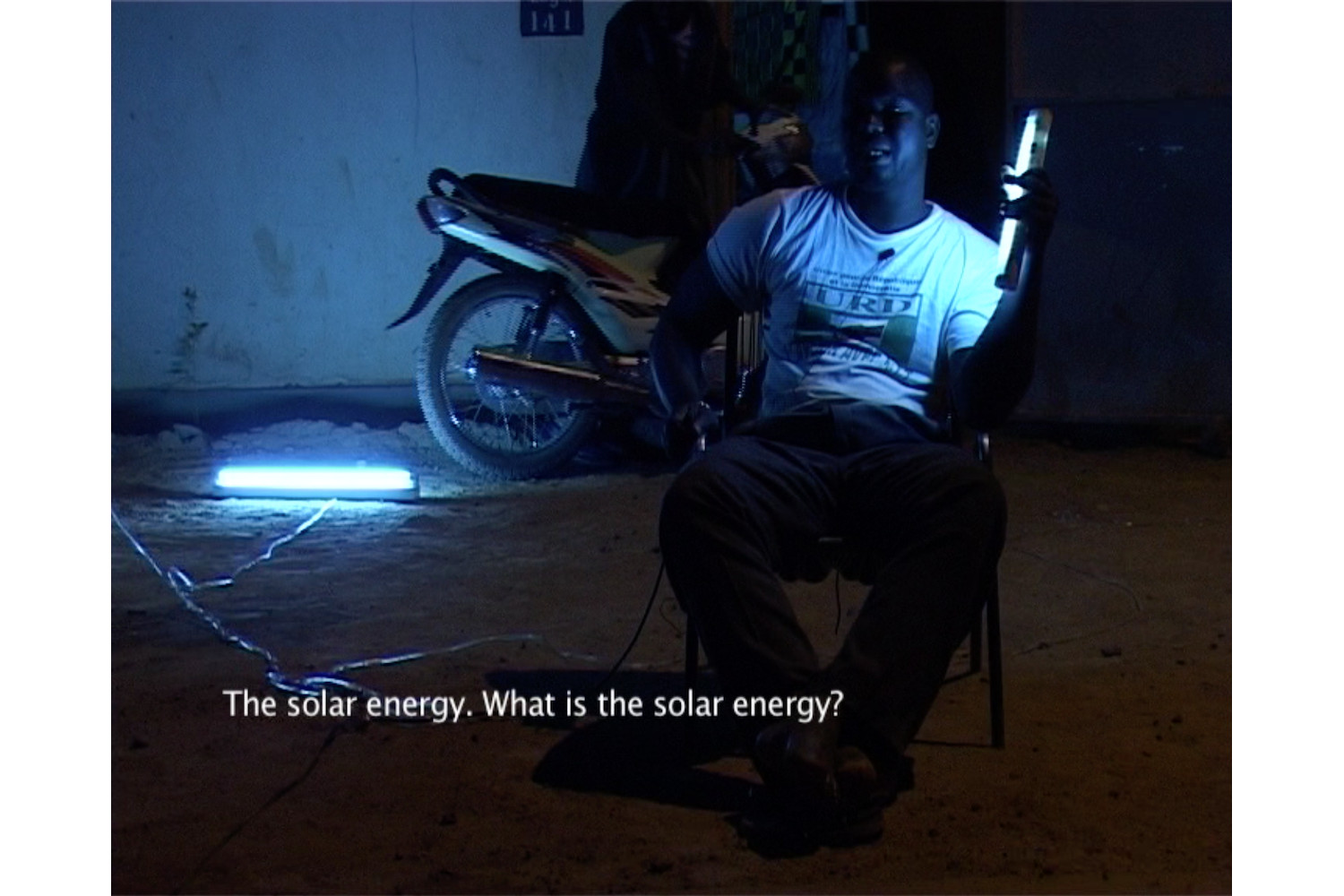

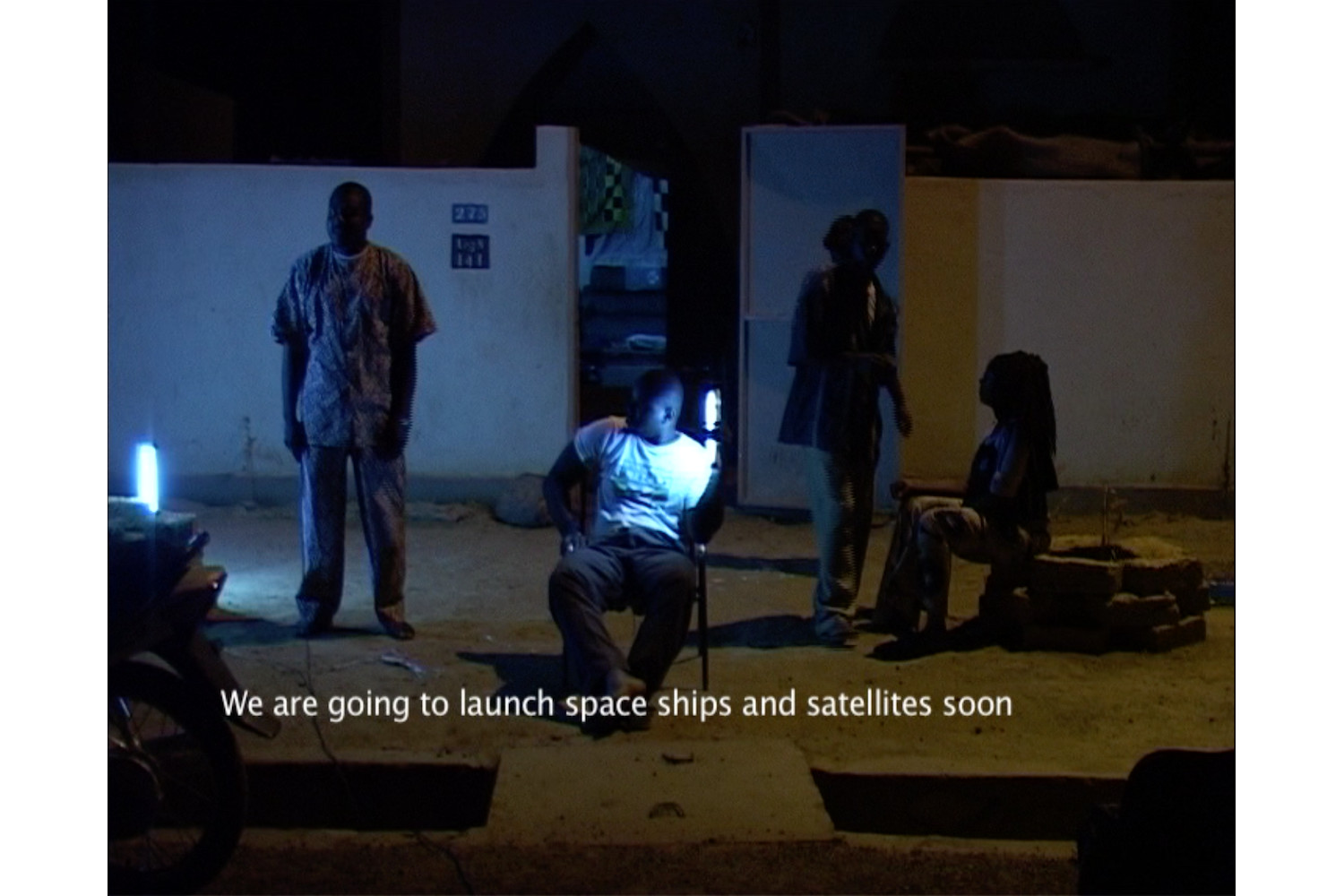

Yet Beloufa’s envisioning of a future pandemic’s external danger in Screen Talk most visibly appears as a catastrophe internal to intimate life. Present to each other and to viewers on and as screens, the characters allegorize the malaise inherent to cognitive capitalism, where digital apps are implanted in psychic life, emotions become quantifiable data to be repackaged and sold back to us, and the sensory dimensions of desire are vanquished as dependency is globalized across long-distance relationships. Beloufa’s exploration of digital intimacy extends from prior films. In Kempinski (2007), a science fiction–imbued documentary shot in Mali where interviewed subjects imagine the future in the present tense, one man foresees that “objects we use make our actions for us” while another fancies that “through telepathy, we make love.” Their future conceptions unwittingly parallel technological mechanisms of emotional capitalism, which Beloufa elaborates in Data for Desire (2014), in which French mathematicians write equations to predict hook-ups within a stereotypical American reality TV show.

Across the Screen Talk videos, the marriage between the frazzled Betsy quarantined in London and the unfaithful Dr. Martin in his San Diego lab is on its last legs, while their depressive son mourns his failed long-distance relationship due to the pandemic’s prolongation of separation. Meanwhile, one of the quizzes on www.screen-talk.com asks viewers to identify Soulja Boy’s song “Kiss Me thru the Phone.” As its title exemplifies, the song is a throwback anthem to what Walter Benjamin called “the sex appeal of the inorganic” and has now become a sad reality of quarantined intimacy. What was once “pillow talk” is indeed now “screen talk.”

In an interview with Maurizio Cattelan, Neïl Beloufa intimated, “I like the idea of a hyperreal world where signs of the existence of a phenomenon replace the phenomenon itself.”3 www.screen-talk.com configures such a ludic digital world, in which paranoid signs of a pandemic’s existence replace the physicality of disease, and the pandemic itself is overtaken by the pharmacopornographic catastrophes of rhetoric and romance. Unfortunately, unlike Screen Talk, for us today the illness in question is no longer just called “hallucination.”