Christine Macel: Navid, I feel your practice is strongly embodied and rooted in the body.

Navid Nuur: Yes, I work very physically with my body. And I do not make a distinction between my installations and my publications. They are part of my work; they are continuous and open doors toward the future, rather than summarizing the past. My work is not site-specific — meaning I do not create something for a site. But I see the site as the missing component that can finish a work that I had in mind, maybe even for years. The site can finalize a work for me. I look for a real equation between the two. My works are not sculptures; they are always in-between mediums. They are like modules that I can assemble. I am very attached to this concept of ‘inter-modularity.’ In fact, I develop my ideas through little sketches, words and notes in my notebooks. Then the work itself dissolves the words, and sometimes some of the words remain in the work. I use stickers to make corrections on my notebooks; but I can still read the previous words and ideas through the stickers. I keep the past and the present as layers. From these notes I test pieces in my studio. The space is for me a living organism, so I try to articulate these modules with space. And the exhibition is conceived as a whole. I am not only showing works in an exhibition space, but also trying to include the city, the people, the public. I conceive the exhibition as an interrelation.

CM: Do you try to redefine the silently preconceived roles of the artist and the curator?

NN: Curator, institution, visitor, critic or collection: they are all just labels. In the end, it’s all about my work and the engagement within this dialogue. I always question these definitions. I question hierarchies in general. For this reason, the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven asked me to intervene in their collection. I chose two works and responded to them, through a dialogue, with new pieces. I chose a video work by Bruce Nauman, Manipulating a Fluorescent Tube (1969), and selected sixteen video stills that represented the different states of his slow body movements and the fluorescent tube. I then used these stills to create a life-size 3-D model out of fluorescent tubes that expressed his sixty-minute performance as one solid, highly charged object. I called it After Bruce (2010) and installed the work next to his video. For the fluorescent piece by Dan Flavin, I wanted to reactivate one of his broken fluorescent tubes. I wrote a letter to David Zwirner, who manages Flavin’s estate, to get some old fluorescent tubes. In fact, I did not send the letter. It became part of a project that is still in process, which I published as a publication dealing with the concept of light within my practice, called The After Glow. For my latest show at the Kunsthalle in St. Gallen, I asked if I could claim the last full stop of the press release as my object. I gave it the title Where You End and I Begin (2007). In the show, this press release will be put under a microscope, and the full stop is enlarged one thousand times.

CM: I have a strong impression of a practice that rejects dualism and any kind of limits.

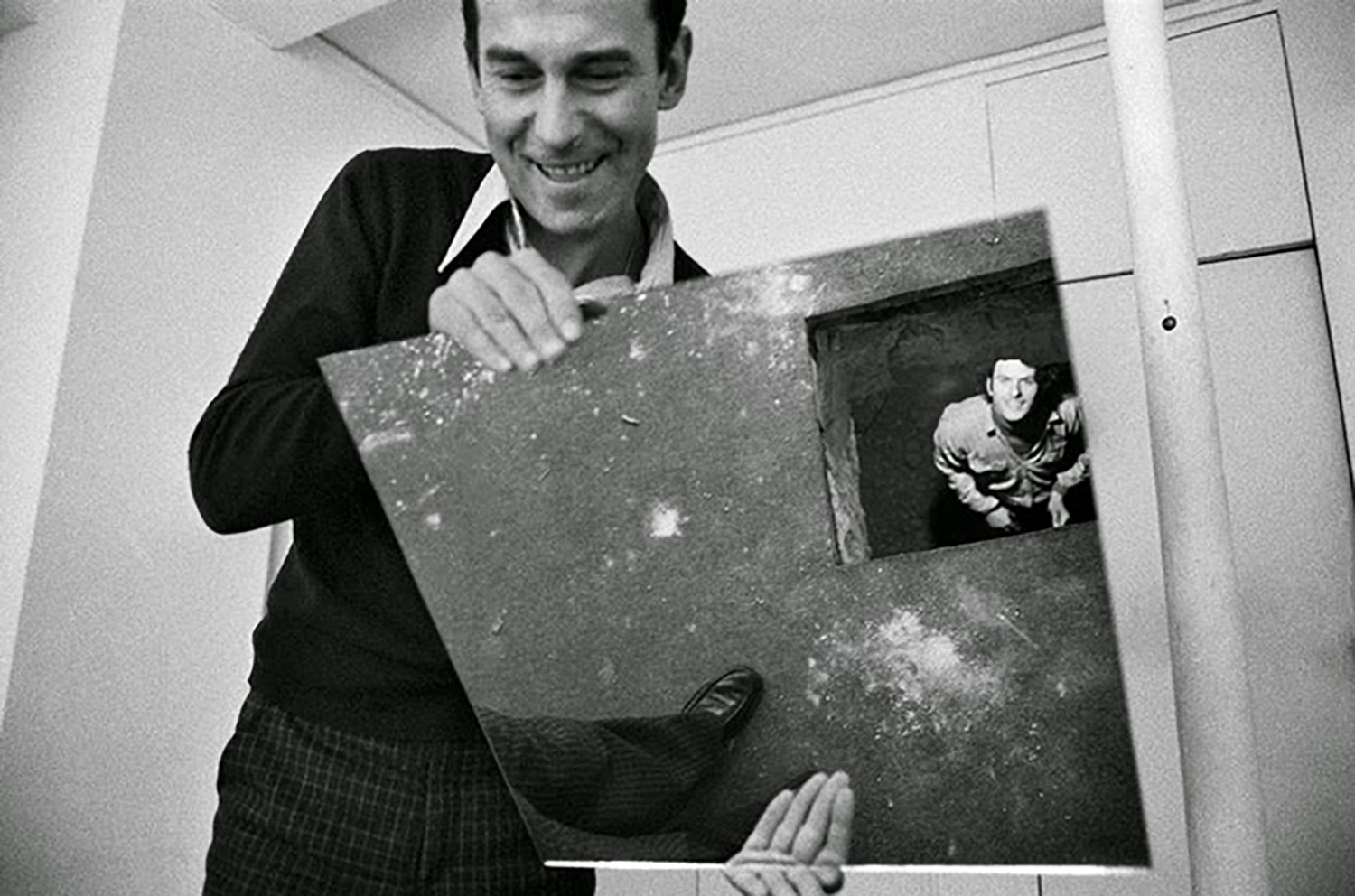

NN: Indeed, art starts where you feel it makes sense, not just where you think it should. For example, I cut out the black oval image in the banner of my show at the Kunsthalle Fridericianum in Kassel, “The Value Of Void” (2009). Then I sent it to my studio via FedEx, where I mounted it on my wall. I took two pictures: one stepping into the black object and one where you see me stepping out with my leg and shirt covered in black paint. These dirty clothes were exhibited in the show, next to the two images taken in my studio. While outside, you see the cutout banner with only the title The Value Of Void. It’s my way of mixing the visible and the invisible, fiction and reality, in an anti-dualist view of the world.

CM: You also question the perception and the representation of the world.

NN: I am fascinated by the fact that almost no one in the world has seen his or her own true face. This is only possible by looking at a mirror, which doesn’t mirror your face. I finally found a special mirror that doesn’t make a mirror image of your face when you look into it. Meaning that for the first time in your life, you can see your true self. This is quite confronting. It also means that self-portraits of masters painted with a mirror are false. The only way to experience, for example, Rembrandt’s true face is by looking at his self-portrait through a mirror. Then you see him as a less secure man full of doubts, which fits his profile much better. I recently found out that 2-D and 3-D monochromes by artists like Anish Kapoor, James Turrell, Robert Ryman, Mark Rothko, etc., all feed from a certain eye coordination movement, which is the same as the movement made when looking at any of the single monochrome works — even at primal monochromes like the inside of a cave or thick mist. Material, texture, color and context define the personal aura of each of these types of monochromes — not the way you use your eyes to look at them. And this is a big thing. So now I am trying to isolate this shared collective eye movement from nature and art history, and use it as a component for some of my new works — works that come closer to my personal experience of perception. This project will be part of a future publication called The Eye Codex of the Monochrome.

CM: Are you interested in neuroscience and especially in the results about vision — the most studied field until now?

NN: It is more about the attitude within the field of science, how they question really everything and how they keep developing methods. Within the field of art this goes much slower and we are too addicted to the results. I use science in relation to my intuition to calibrate all my senses to experience more delay with encounters in life: a delay that allows you to experience other things while you are looking at the same thing.

CM: You work with sound mixed with sculpture in an original way.

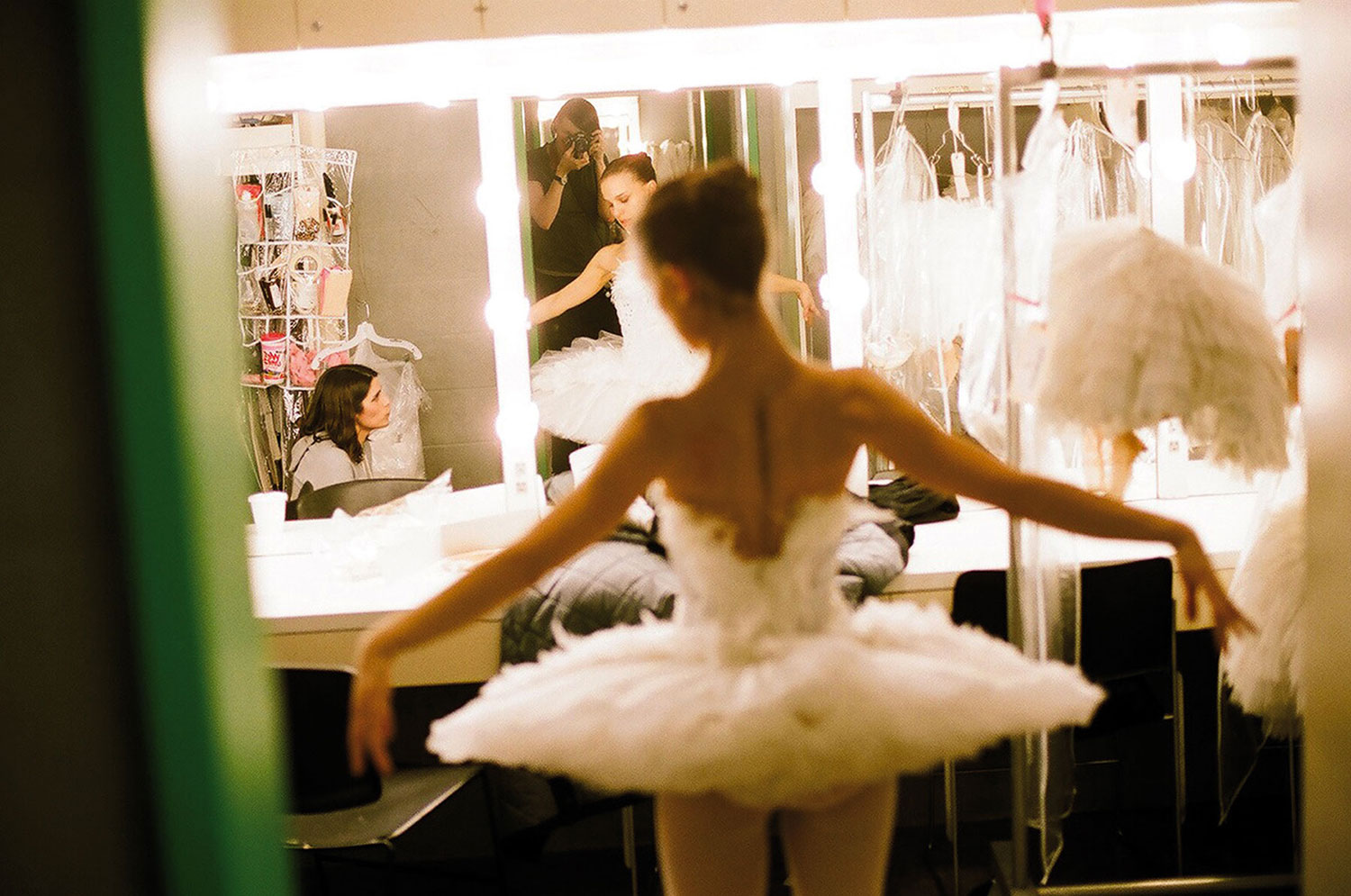

NN: If you record sound, you can hear the past while looking at the present. In the piece redblueredblueredblue (2009) I mixed red and blue Plasticine, while expressing the name of the colors in relation to the amount of pressure it took me to mix them. So while the object became purple, it was still connected to its past. At this moment I am working on a project involving two dancers, two amplifiers and two sensor lights. In almost darkness, both dancers, standing far left and right, have a microphone taped to their feet, which they drag slowly across the floor so that you hear the work in stereo. The tempo of their movement depends on the light sensor. This will switch on when one of them goes too fast, making you suddenly see the posture of the dancer. Almost like a photo still. When the dancer keeps still, the light pops off and the slow movement can start again.

CM: You also danced yourself in an involuntarily funny way in the action you did in collaboration with the Van Abbemuseum and the city of Eindhoven.

NN: What is interesting about these sensor lights that are meant to keep people away at night is that if you walk really slowly, they don’t detect you. It is as if by being very slow, you can become faster than light. It is a beautiful contradiction mixed with a lot of cinematic atmosphere and improvised choreography.

CM: Can you deepen your relationship to politics in your work? This piece is obviously linked to the surveillance systems that private or public people install looking obsessively for security.

NN: I was doing a lot of graffiti when I was young. I think I miss this mix of illegal creativity, trespassing and after-midnight tensed silence. I am glad it bumped back into my life and works from a different point of view.

CM: What is your dream for now?

NN: ΔS = ΔH / T