With great homogeneity of purpose, French artist Mimosa Echard’s work unfolds from one exhibition to the next in an ongoing formal renewal that challenges the limits of expanded painting and sculpture. Each exhibition makes reference to those that came before, providing a syntactical scaffolding in support of stunning innovations that liberate Echard’s work both from its intense materiality as well as any risk of repetition.

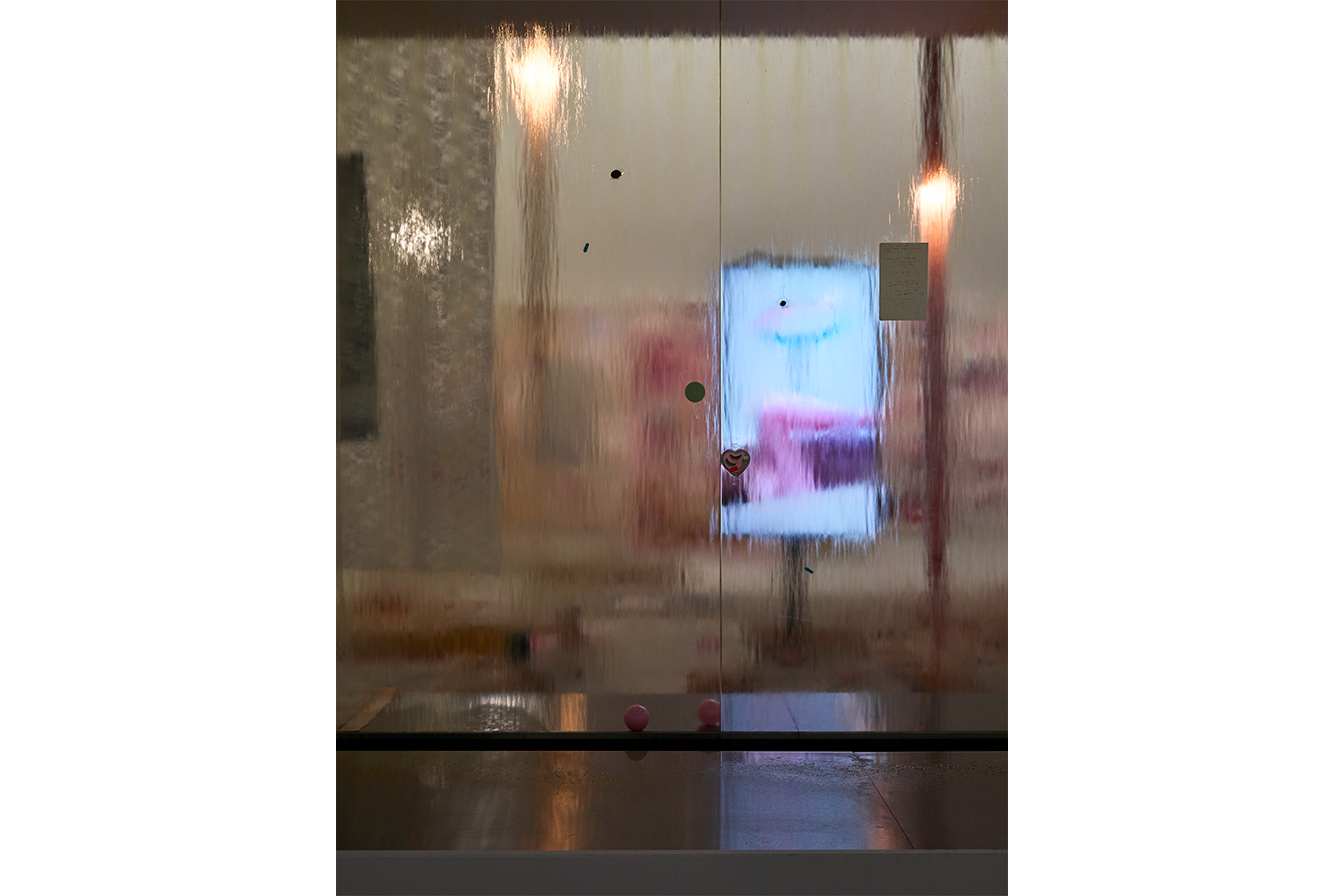

Escape more (2022), her installation recently on view at the Centre Pompidou as part of the 2022 Marcel Duchamp Prize, for which she was awarded top honor, seems to be a quasi-architectural piece. At first glance it appears to be to be embedded — almost hidden — within the thickness of a wall in the exhibition space, but it turns out to go even deeper, as a kind of metaphor or synecdoche for the artist’s entire oeuvre. The uninformed visitor could almost walk past the work without really seeing it, as if it only required a swift glance — just as there are some swift nudes1 — but that, indeed, is not the case. Escape more consists of a large rectangular display window that brings to mind a vivarium or a diorama. Its slightly disjointed — in infrathin dis-adjustments — glass panels reveal a large space that could be the artist’s bedroom or studio, the walls and floor of which are partially covered with two-dimensional red or pink monochrome elements. These appear to be chromatic tests for a palette or a pictorial work, with subtle echoes of recurrent colors in Echard’s other works. In the midst of the vitrine, magnetizing the gaze, is what may surreptitiously appear as the artist — or not — naked, successively sitting or lying on a bed, evoking updated pictorial figures2 or their revisited versions in the modern and contemporary artistic field.3

These monochrome elements, like the moving nude4 images that are actually displayed on a large vertical monitor within the installation, are blurred and partially concealed by a curtain of transparent liquid that flows vigorously along the glass walls and continuously submerges them. Escape more, like all of Echard’s works, is above all about the gaze and the viewer, the artist’s game with the latter; about scopic impulses and how they are thwarted: the gaze seems to be at once shrouded in desire and prevented by elements that act as a screen. Escape more’s liquid flow is this impediment, which simultaneously conceals and reveals — thus tracing a “liquid or lachrymal painting.”5 It is redoubled by several girly elements, some of an aphrodisiacal or fetishistic nature, that can be seen at the front of the window. A key part of Echard’s syntax — in which nothing is left to chance — they might seem cute or vain, but in fact contribute to the formation of a powerful landscape with multiple meanings that is articulated around a reinvented pictoriality with a hidden erotic charge.6

Glued next to a metal ring affixed to the window with simple tape that slightly obstructs sight, a pink plastic heart serves as a box for a pair of “Magic Girl” false eyelashes that look like two closed eyes. They may bring to mind the eyelets through which it is possible to observe the nude that is hidden from the gaze,7 but they actually obstruct vision, depending on the angle at which the viewer is positioned. Some white lace and gauze with feather elements, affixed like a curtain that evokes a bridal veil,8 cause a redoubled blurring of the vision of a small girly cat — or more likely a female cat, as the French chatte is the equivalent slang for pussy — in front of which is placed a bald, pink, plastic ball: one inside and one outside of the glass, with a potential erotic charge that focuses the gaze, like the sheet of paper torn from a notebook with scriptural elements on it that is directly taped to the vitrine. All of Echard’s Seeing Machines are thwarted, as they are also Machines-For-Not-Seeing that put the viewer in the position of a voyeur — but a voyeur who cannot see. Here too there may be “Water and Gas” (light)9 “on every floor,” as well as Gaz(e),10 even.

Inserted high up in the layers of feathered gauze — in French gaze11 — three vast and mysterious white-and-gray elements seem to take up the motif of a Milky Way observed through a window whose frame can be seen.12 Looking pictorial in nature, the elements in fact result from a photographic transfer process.13 A small photographic image of an open French-style window with lace or net curtains that seem to flutter in the wind seems to complete these secret reminiscences, in possible allusion to essential figures in the history of art.14 15

Still, the interpretation of Echard’s work is always multiple and the meaning layered, partly secret, or unspoken. The liquid flowing powerfully over the glass could, according to Echard, recall Golden Shower (1998), an Alexander McQueen fashion show produced with the support of American Express,16 during which the models, dressed in white, seemed to be showered with a yellow liquid, conjuring Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), whose erotic subtext is also well known, or other more Pop works, such as an iconic Warhol. In fact, Escape more also refers to mare’s urine, from which synthetic estrogens are derived for use in drugs that have done irreparable physical damage to women; and to women’s urine, from which their own estrogen and drug levels are measured.17 Yet the elements visible on the walls are made from a series of advertising images for these drugs,18 and this “lachrymal painting” might be a mourning ode to these women. Body fluids, a recurrent notion in her work, evoke what unites Man with Nature, and what links Man to Machine — here by way of a reference to the two apparatuses in operation.

In that sense, according to Echard, Escape more might also recall the money that floods certain sectors — a flow symbolized by the walls of water that can be seen in corporate headquarters or in certain spas.19 The glimpsed nude might therefore be in the equivalent of a Turkish bath20 near a (spa) waterfall.21 However, a small monitor, half slung across the front of the display case, shows old footage of her sister Othilia cleaning out a clède that her two older sisters had converted into a bedroom: Echard emphasizes the analogy with the desire to create a “pure” space like the exhibition space, and the impossibility of this desire. This video also includes the motif, recurrent in Echard’s work, of a rectangular pink basin — of which we also find a specimen at the front of the showcase, here containing pigments that correspond to the chromatic range we see on the walls.

Echard’s Large Glass renews the painting-form and the notion of expanded pictoriality. Escape more appears opaque or illegible at first glance, but the work is accompanied by a set of textual and non-textual elements that provide elements of understanding and make it possible to envisage it nourished, or irrigated, by a set of references in a kind of secret rhizome, one of the dimensions of which corresponds to the title of the Prize22 in an extensive game of allusive clues and references. But these are not monolithic, and they intersect with sets of meanings specific to Echard’s work.

Materiality of a secret and mysterious work

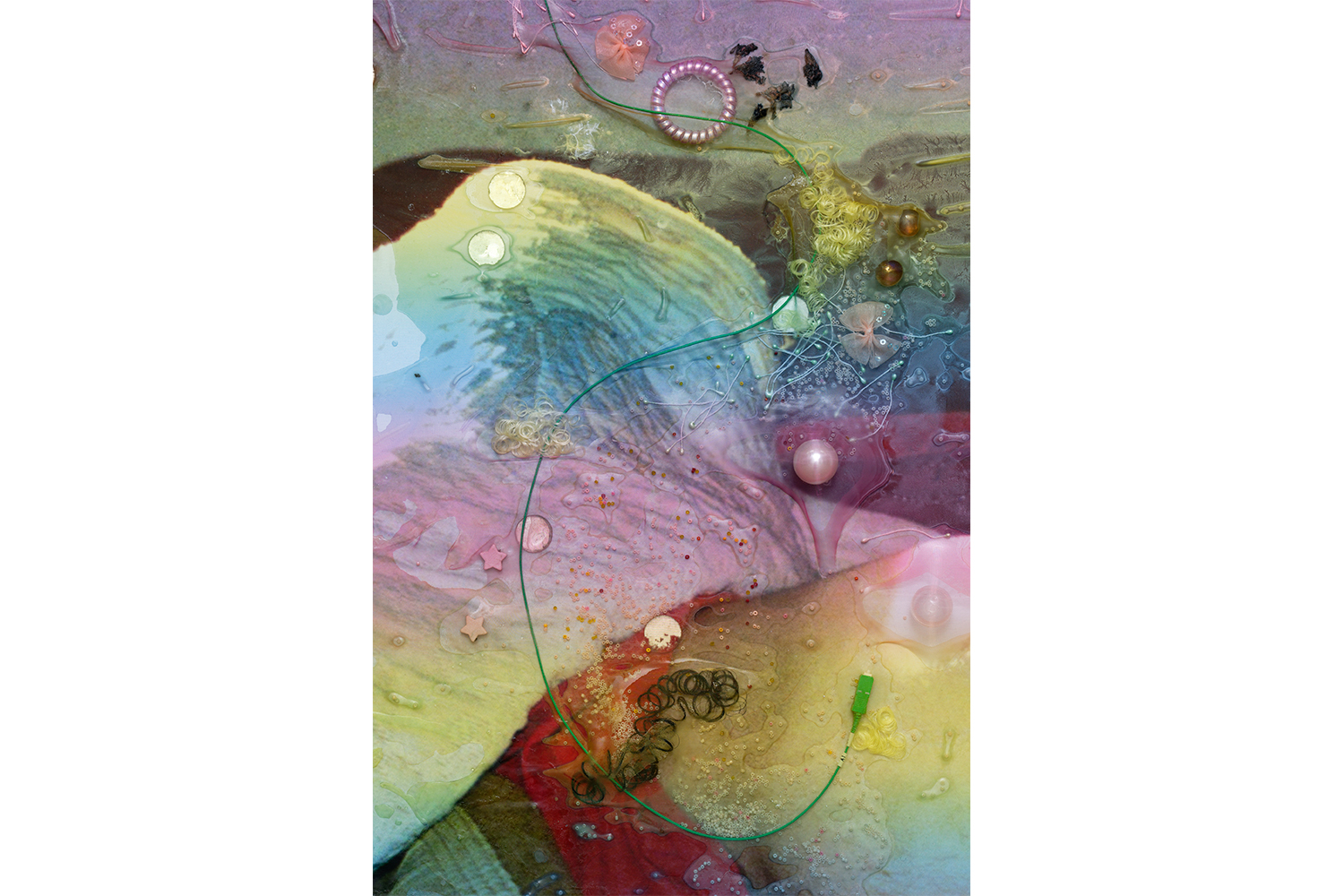

This reinvention of pictoriality is one of the constants in Echard’s work, as well as introducing into it various collected girly and unique materials. In one of her first series, titled “A/B” (2016),23 large plexiglas frames seem to form abstract paintings, but their “Face B” reveals their rough materiality. Comprised mostly of pink hair-removal wax, which forms a set of intertwined shapes that bring to mind the way it spreads when using it, it thus evokes an adolescent world where painful tearing-away turns into a girly sororal wax-sharing party. However, it can also bring to mind the erotic art-historical obsession with hairs and shaving,24 as well as a magical world in which hair is used to make potions. In fact, the series is made from a set of materials that constitutes a kind of magical pharmacopoeia: seaweed, lichen, kombucha, phallus indusiatus mushrooms, ginseng, clitoria, St. John’s wort, chamomile, eggshells, flies, Diet Coke, glass beads, false nails, car body parts, contraceptive pills, etc. These items add up to a set of meanings that become active when read, and reveal their mysterious, geometric complementarity and ecosystems, wherein plants and manufactured products, living and non-living, coexist. Their magical charge also comes from their collection method, as some materials are carefully gathered by Echard herself in shops, while others are mainly collected in the Cevennes countryside by the inhabitants of the village where she grew up,25 to become part of a carefully preserved archive for future use in the studio.

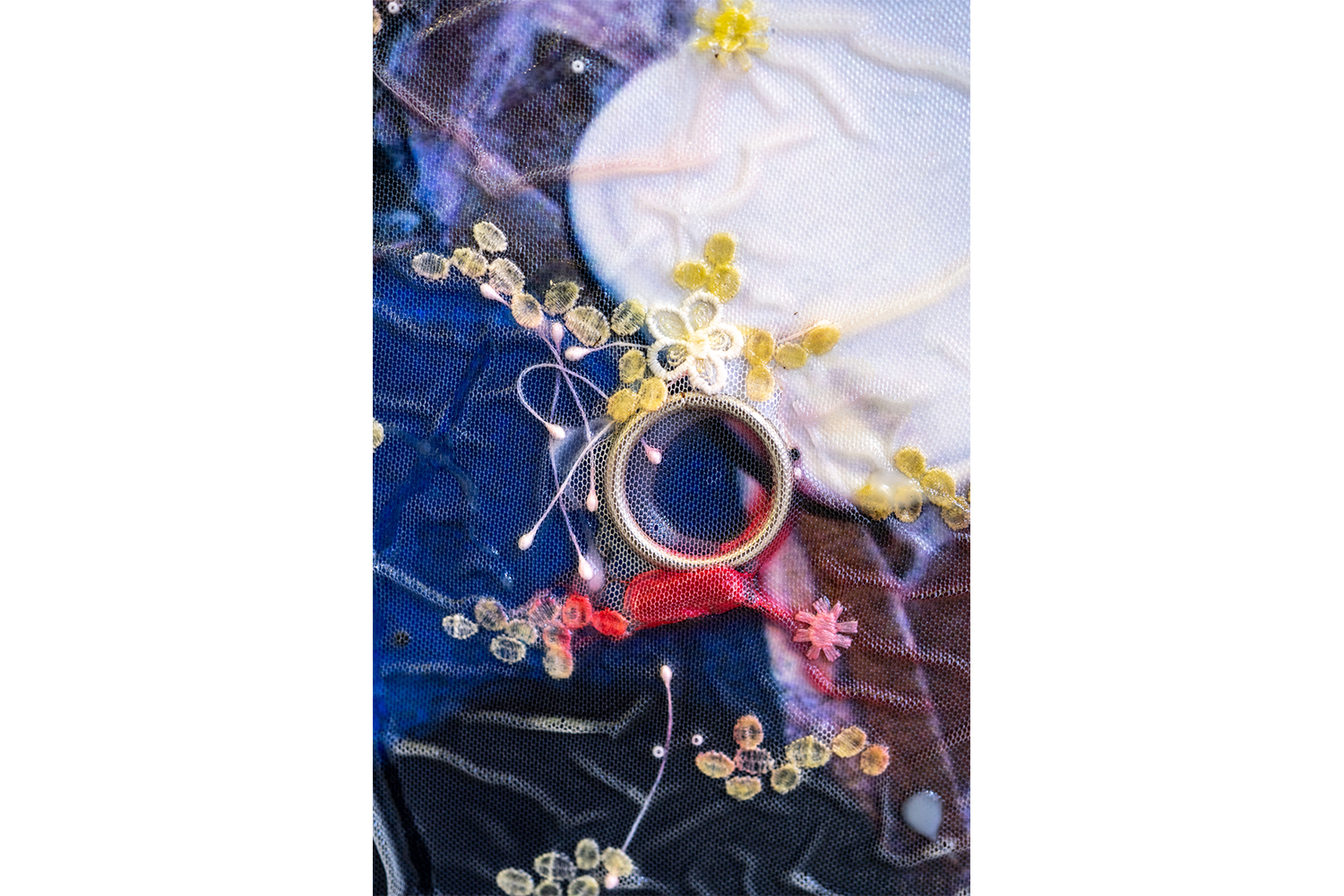

This unique material basis was obviously present in former works, but the important “Numbs” series (2021) has broken free from the preeminence of the language of materials, although it still draws on the same syntax. “Numbs” are large-scale pictorial works on canvas with the repeated photographic motif of a semi-nude androgynous figure, possibly taken from personal or family archives, lying three-quarter length and partially dressed in a T-shirt, showing their buttocks to the viewer. The canvases are augmented with painted elements and various girly or erotic objects — small bracelets and necklaces with red and pink plastic hearts, fake flower pistils, geisha balls — that cover the image to various degrees. They are all unified by fluid materials such as latex, glue, or acrylic paint, which solidify when they dry, thus uniting the elements through a process of chemical transformation that seems to fuse the materials and give them a new dimension.

Recurrences, transfers, superimpositions

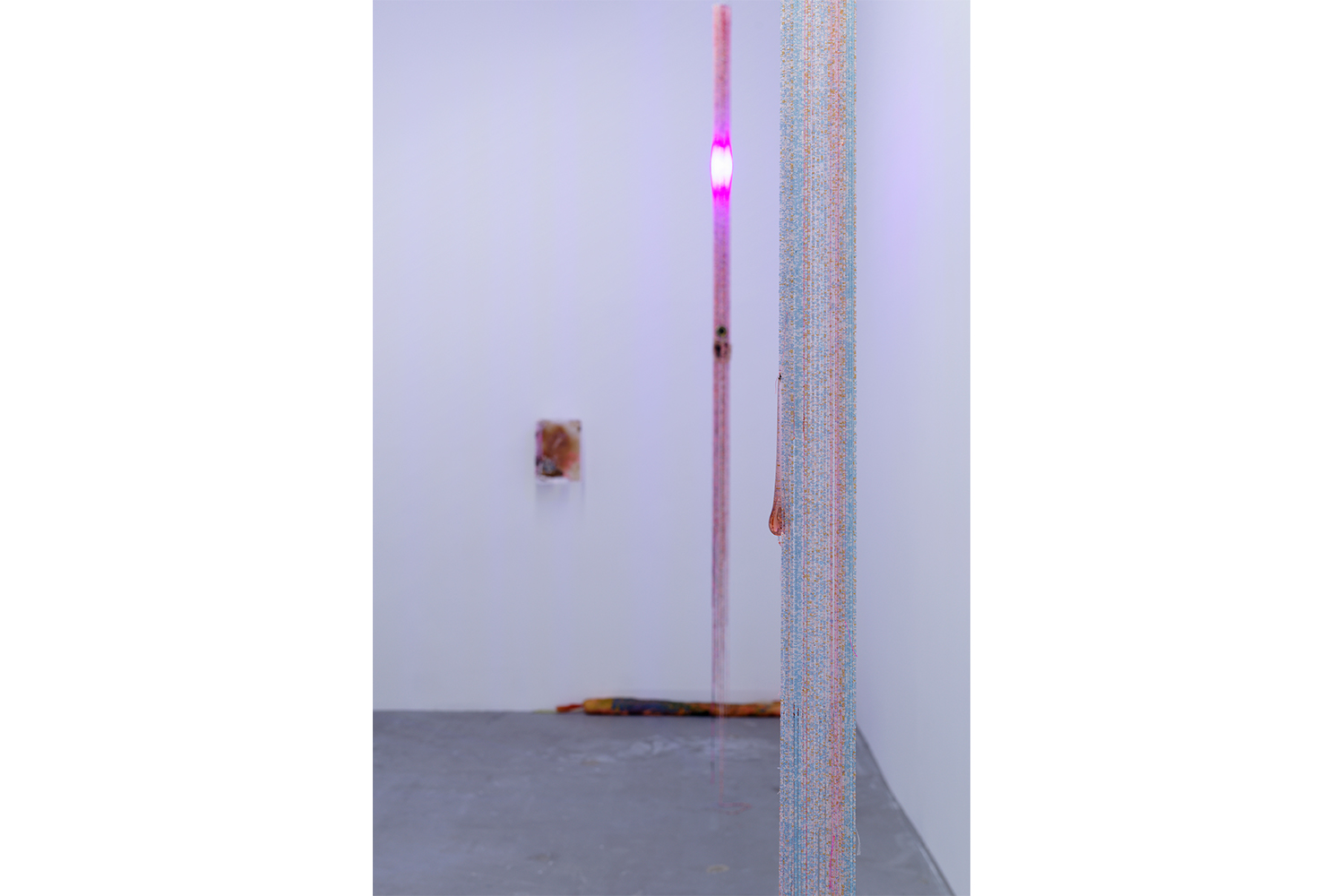

Echard’s second exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, “Sporal” (2022), escaped more from this kind of materiality. The ensemble of works shown were based on motifs from Echard’s eponymous video game, Sporal (2022), based on the hydrophilic modifications that occur during the reproduction process of a myxomycete, a single-cell organism similar to a fungus that escapes traditional animal and plant biological categories, and has 720 sexual variants. The game explores, in an epic mode, a set of dreamlike images, the cavities of an organism undergoing constant transformation.26

The exhibition’s central visual element was a reprise of the syntax of the curtain that is recurrent in Echard’s work, in this case as a quilt made of various fabrics augmented by photographic transfers — here composed of images of psychedelic motifs, documentation of the game-making process, and the game developer’s bank of personal screensavers — upon which was projected a video from the game. The exhibition was presented as a journey during which visitors could download Sporal, and where they encountered a series of works related to the universe of this game and constitutive of Echard’s vocabulary, such as rectan- gular plastic basins containing technological, erotic, girly, and natural elements affixed to painted backgrounds. A sumptu- ous, violent, almost fluorescent-pink work attached to the wall consists of a set of elements entirely obscured by a thick paint material, at the center of which is a small photograph that is reused in a video projected onto a second large screen that constitutes the key to the installation.

This second video shows a succession of different characters sleeping. One of them, partially naked, constitutes the basis of the pictorial series “Numbs” (2021). It recalls Warhol’s Sleep (1964), or the people on Twitch who self-film themselves while asleep. In front of it, a set of cushions filled with various elements is placed on the floor, inviting the viewer to rest while contemplating the video, in a mirroring set-up.

Mimosa Echard’s powerful work unfolds a layered interplay with the viewer that is full of secret meanings and art-historical references. Its recurrences constitute her personal syntax within a constantly evolving visual reflection that carries on from one exhibition to the next. Their archaeological stratifi- cations, nourished both by her own intimacy and by collective and universal meanings, echo the complex and historicized weaving of thought, as well as the stratification of art history.

(Translated from French by Charles Penswarden)