There is something fluid in dance. It lies neither in the quality of the action — obviously kinetic — nor the sequential nature of any choreographic composition; rather, it is a general viscosity that envelops the dancer. As if submerged in an unstable environment, the body moves between the tensions it contains and transforms them, through dance, into sensory experiences, configurations of equilibrium, or ongoing changes in state. To employ a scientific image, the mise-en-scène presents itself not just as an aesthetic or narrative structure, but as a system of forces that is affected by constant energy inputs even when stable, manifesting itself through volatile phenomena or perceptible materialities.1

Michele Rizzo’s work follows roughly the same dynamics: each dramatization springs from a milieu of intangible stimuli that flows into choreographed bodies, alternately transforming itself into energy or matter, and building up a constant electric potential. The process of constructing these performative experiences is not limited to governing a single event; rather, it is like a continuous stream, with force after force splitting it into different stages and states. While preserving their own ecology, the projects that Michele Rizzo has created in recent years follow the same kind of sequence, and can thus be ranked, so to speak, into a trilogy where body, movement, and space are used as alternately stable components. In a clearly approximate initial reading, one might say that HIGHER xtn. (2018–19), Spacewalk (2017–19), and Deposition (2019) have transformed into each other, pursuing the unspent potential energy that flowed through each; that they have expressed each shift with scientific rigor or ambiguous mysticism; that in each movement, they have recognized a grammar controlled by the body (not the mind); and finally, that the entire process has continued its slow, dynamic advance and crystallized, monadically, into specific events or objects.

In the exact moment that one or more performers began dancing to the musical composition by Lorenzo Senni, or perhaps even before that, when the score was conceived and written, an accumulation of potential energy was discharged onto HIGHER xtn., creating a surge sufficient to fuel the entire trilogy. This “virtual” material — the artist’s imaginary, which is “actualized”2 during every performance — provides the energy needed to turn the body into a conductor; in Rizzo’s works, it is translated into actions with a specific kinetic order and experiential ends.

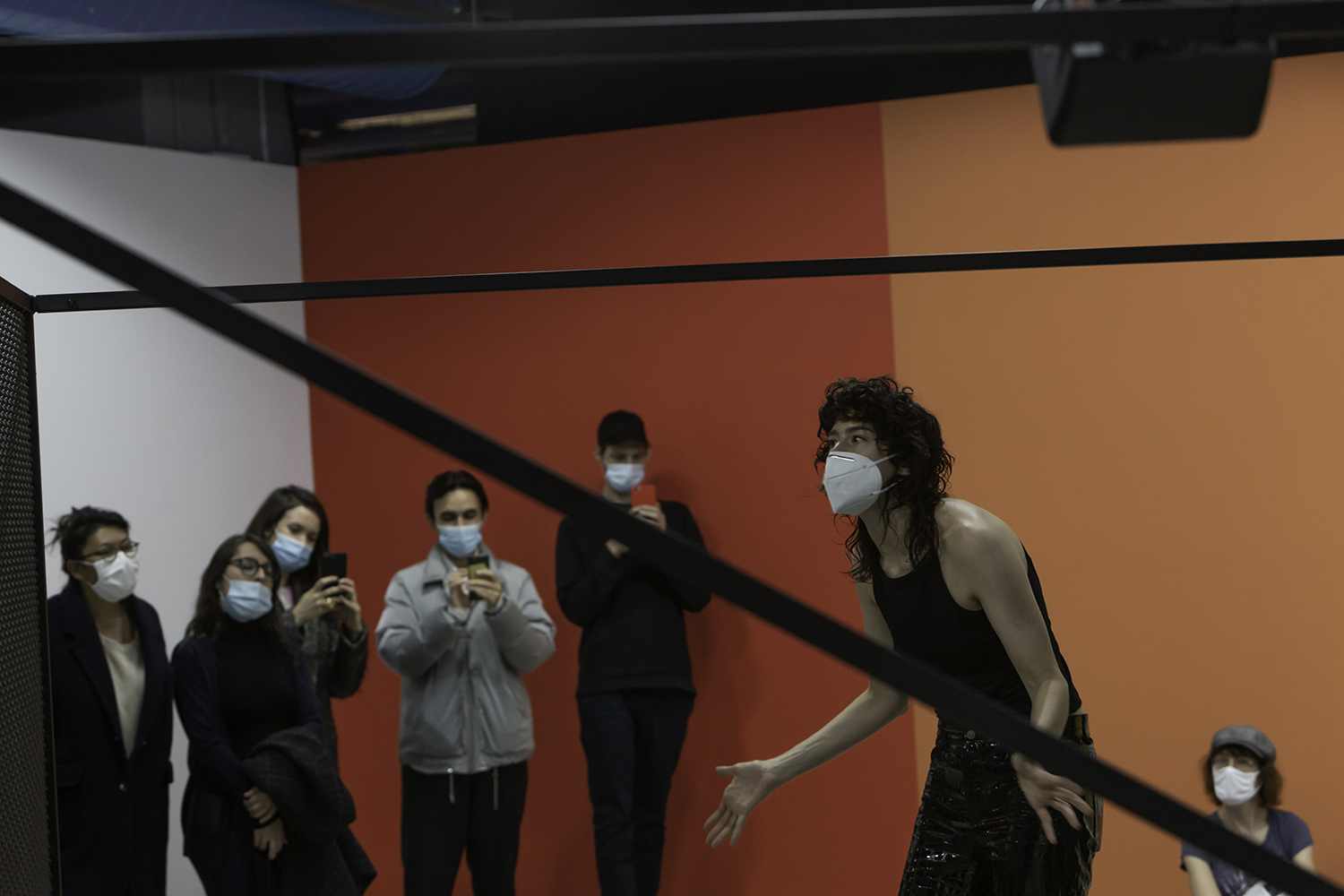

Were it not for the rhythms and aesthetics it borrows from the clubbing scene, for instance, HIGHER xtn. might pass for a ritual similar to any religious, secular, or folk dance that serves a social function. In all of its configurations, a varying number of bodies occupy a space of varying nature,3 moving through it to the beat of music that gradually grows more intense. The constant injection of energy from the score creates a corresponding acceleration in the dancers’ movements and leads to a general catharsis, a “boiling energy”4 where the individual’s identity merges with that of the community. Generating a much higher voltage, HIGHER xtn. becomes a system of independent forces that, to extend the scientific metaphor, is fueled by the surrounding viscosity, producing altered states that in this case turn into a trance. The clubbers defy the control of mind over body, hammering away at it through intensified movements until consciousness is suspended, fluidly melding with the milieu of stimuli.

The ecstasy (ex-stasis = out of place) achieved here — that physical/mystical space between experience and consciousness — is simply a new state of potential energy for the trilogy: a new virtual stage where mind and body once again become entities capable of lending a tension to be actualized. Michele Rizzo imagines it as a literally “outer” space and explores the experience of moving through it.

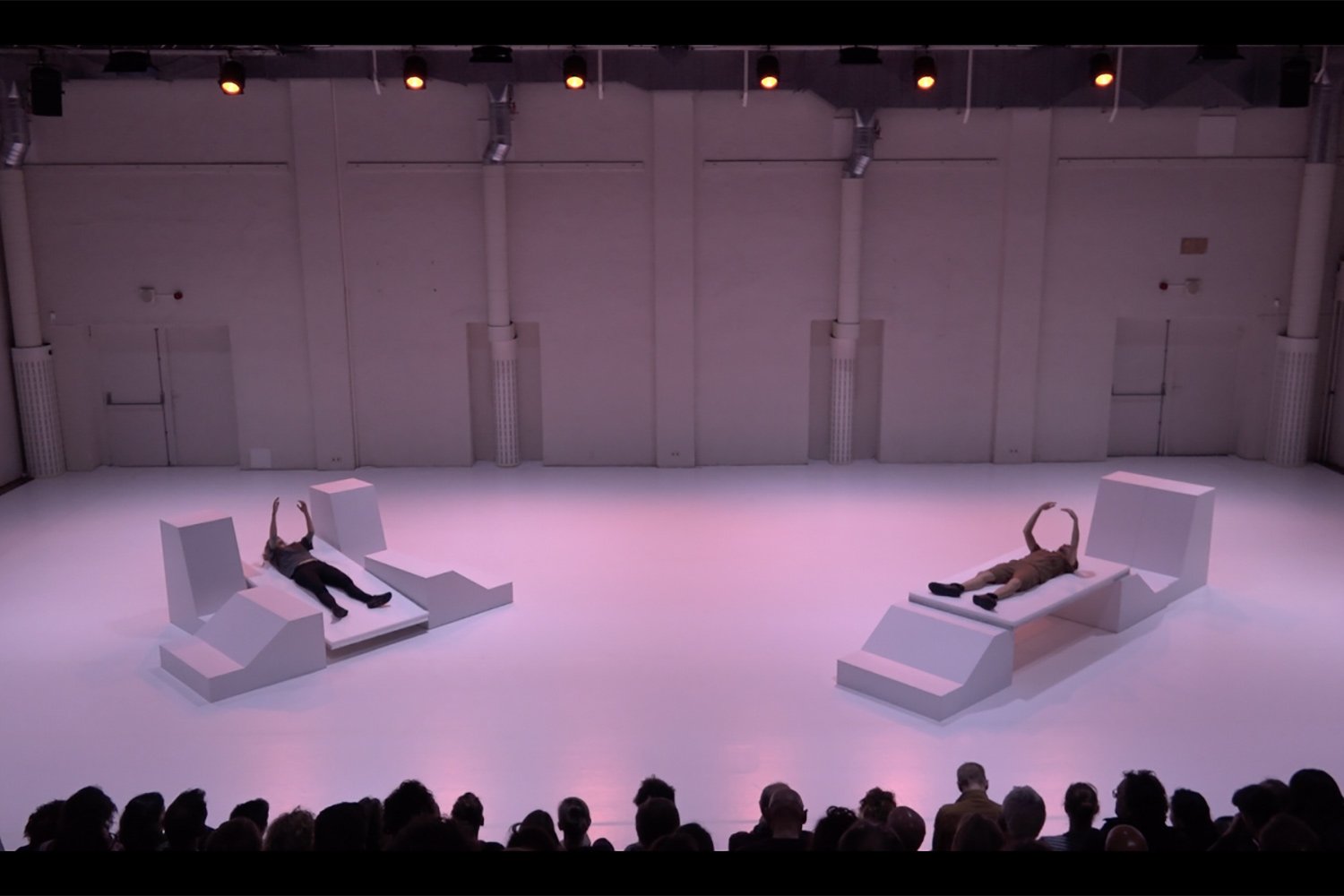

Conceived for the stage before it became an installation, Spacewalk is the physical and aesthetic reconstruction of an elsewhere occupied by ephemeral architecture: an imagined heterotopia5 in which all constraints of reality are suspended, leading to a full unfurling of virtuality at both the functional and identitarian level. Moving through an archeological/spatial landscape scattered with plinths and motorized prisms, the weary bodies of the performers, as if drained by some previous effort — conceptually, that of HIGHER xtn. — slow their movements to the point of seeming immobility. Stretched out on a few derelict structures, with their swaying arms raised, these cosmonauts bring the tension back to near equilibrium, perfectly controlling the exchange of stimuli between matter and its surroundings. As in HIGHER xtn., the dramaturgical dynamics of Spacewalk also unfold in their own way; while participating in the energy flow that runs through the whole trilogy, it strives to preserve the ecstasy that has been achieved. In a metastable system,6 the unconscious mind is free to move through every state of the imagination; to dwell, peripatetically, on its many facets of identity, which it comes to contemplate with an altered (and more sensitive) awareness of space. Even at the point of maximum stasis — when the performers stretch out in the cosmic space built around their trance — Spacewalk in no way has the complete immobility of a system in perfect equilibrium; rather, it has preserved the previous potential energy, waiting to release it in a new change of state.

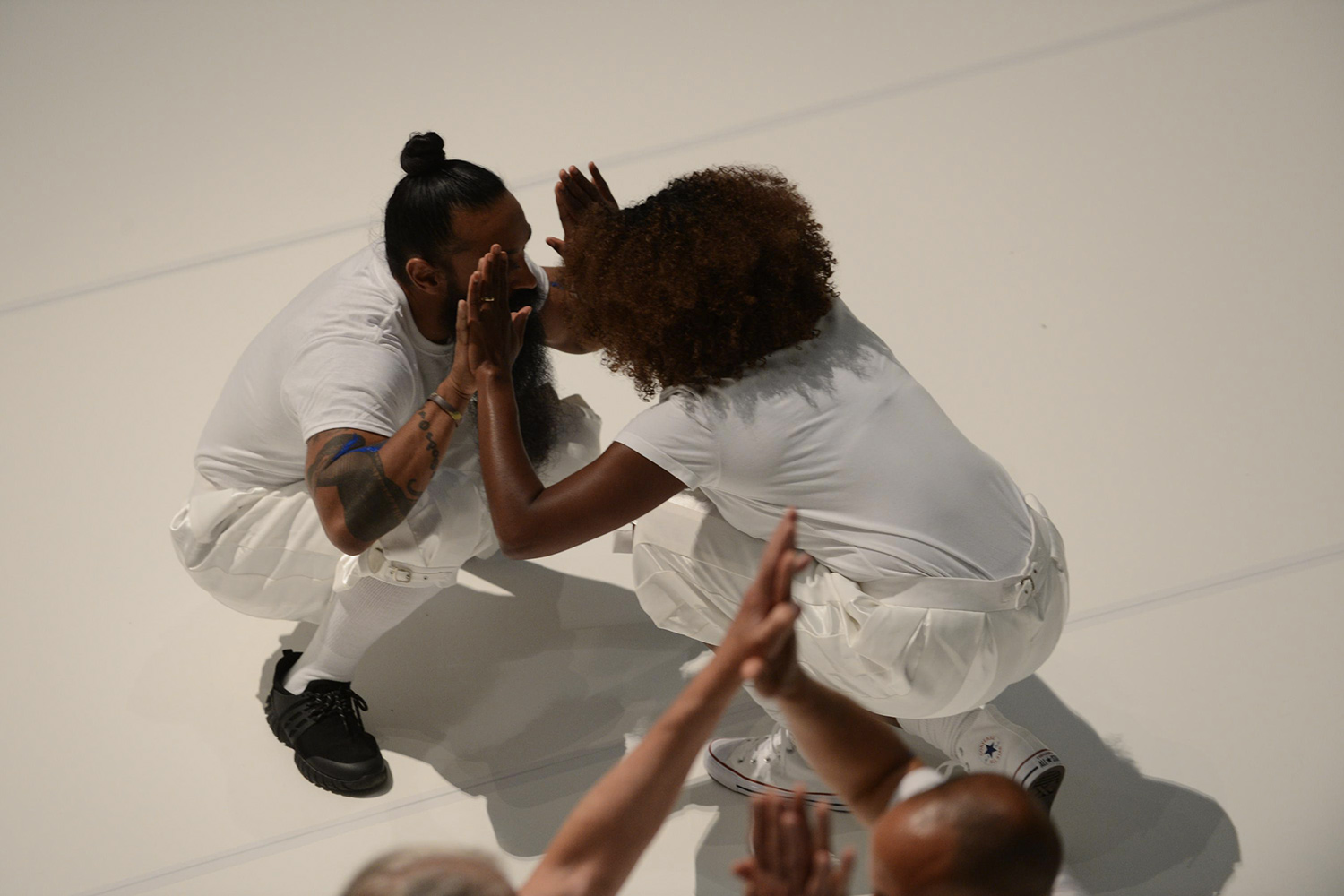

Deposition is thus the next necessary step: breaking out of ecstasy to give energy back to matter, consciousness back to the body. A single performer, Rizzo himself, moves around a chain stretched across the middle of the stage. Its verticality is what must be descended to emerge from the virtual sphere, its materiality is what must be recovered to enter the physical world. The movement performed by his body is slow yet anything but light, the energy is stable but not constant: the tension of the previous trance state is transformed into gravity, and matter is suddenly pulled down by its weight. When the dancer comes to a halt, guided by the falling rhythm of the music7 as his movements slow and then reach a complete stop, the potential energy of the deposition — like that of the whole trilogy — is discharged, returning to a minimum until the next performance.

The entire dramatization is anything but definitive — on the contrary, it is poised to reverse this outcome. This mutability resides in the precise mimesis of the bodies on stage: their organic nature turns it into living matter, their changeability fuels it with an endless transmission of energy. Were this not the case, each work would continue to exist in static equilibrium or would crystallize into a form like one of the inanimate sculptures that also fill Rizzo’s imaginary. These people made out of clay or resin, sensual bodies frozen in hedonism, are inorganic fragments that accompany the performances as witnesses and traces of them, fossil energy that is no longer potential.

The installation Rest (2020), presented at the Rome Quadriennale without its full accompanying performance,8 appears to embody this respite. Four sculptures — carried into the exhibition space in a brief processional and laid out on carpets that are like high-tech shrouds for their deposition — seem to be the inorganic precipitate of a physical phenomenon; a warning of what happens to matter drained of energy; or more simply, the sign of a journey that has left traces scattered behind. Whether they are seen to resemble the clubbers of HIGHER xtn. or the cosmonauts of Spacewalk, these works are a materialization of such performative acts, becoming simulacra of the sensory experiences in them. The hand-sculpted forms, whether reclining or sitting, whole or dissected on ceremonial litters, become tests of the resistance/existence of the virtual within the real. Charged with performative potential, they serve as an immobile reference in the panorama of forces choreographed by Rizzo.

With their initial fluidity, moreover, all of Michele Rizzo’s bodies constantly defy the viscosity that surrounds them, emerging among its tensions like power relays: incubators and transducers of potential energy, whose physical form is only an interface for self-representation. Every change in state, every discharge of energy, every movement of matter helps the subject achieve expression, allows the subject to observe the world without and within, and to process — from a safe, privileged position — the information transmitted by this organic shell.

It is the body, immersed in reality, that explores “viscosity.” The conscious mind, on the other hand, is tasked with receiving the stimuli of sensory experience, synchronizing itself with its surroundings, and converting multiplicity into “identity of movement”9: into a generative force that sculpts gesture step by step.

This is what constitutes experience, especially the performative kind: it means responding to the changes and tensions of a multifaceted reality and, suspended in this ebb and flow, grasping and savoring its milieu. Even when they take on fixed form in clay, Michele Rizzo’s actions dance out a trajectory, and, like any activity that does not sever experience from praxis, they do so because they must: because movement is their tool for interpreting reality, and reality is a constant alternation of energy and matter.