Luigi Alberto Cippini One day, I was trying to get out of software boredom and I was browsing for YouTube content. I have this hate/love relationship with art galleries, as they are spatial constructs as diffuse as the air. Hence I truly enjoy spending moments of the day looking at these replicable spaces and charting them as a sort of spatial and visual tasting experience. I found this video uploaded by user gilda snowden — a YouTube account with 733 followers — and titled “MICHAEL E SMITH AND KATE LEVANT at the SUSANNE HILBERRY GALLERY.” It’s an incredibly honest and happy video with fine-tuned found-footage kinks. In the video, a positive and feel-good voice comments on the show and the works exhibited, together with Kate Levant, in 2007. I rushed to Google Street View and typed in “700 Livernois St, Ferndale, MI 48220, United States,” the address of Susanne Hilberry Gallery: this nondescript single-floor building where the gallery was housed is incredibly interesting to me; it felt demoted and the purest platform for an explicit rendition of the intrinsic complexity of American art. After a couple of views I was convinced that no other gallery — and no other exhibition — could be so in sync with the US. And then I saw your exhibition at KOW, Madrid, in 2019. I was so amazed. The show truly spoke to me. I particularly remember that YouTube video. I often go back to it, simply because I enjoy looking at it.

Michael E. Smith I could talk about that video for a long time. I don’t know where to start. There’s two chapters, I don’t know if you noticed that. It hits me like a home movie — on top of all the rest you’re getting at — and a memorial.

LAC: As somebody that doesn’t know how the exhibition at Susanne Hilberry Gallery unfolded, I think you can see a sort of unfiltered matter, something that looks destroyed – like a car window completely smashed. The image of the YouTube video is quite grainy, and at a first look you don’t really understand if it is you or Kate Levant the video is showing. By taking a better look at it, you start understanding who is who, and an image starts unfolding in your brain. In that particular moment, your work seemed completely different; it was very loose, but at the same time, it seemed simply a solid and deep version of something artists are always forced to do, which is new work. I feel like that peculiar show was “insane” in relation to the work you have been doing lately, as well as how Kate Levant’s practice has evolved. I am still very curious, as that video is sort of embryonal and incredibly resolved at the same time. The camera points at a room where three works by Kate Levant — a ruined car door, an air-filter grid, and what seems to be black and light chains on the floor — are placed next to one of your Untitled works, namely a set of black vase-like objects and what I think are burned objects scattered in direct proximity to the gallery’s glass facade. Me and my friends are constantly obsessing about this video because we have zero information about who is who. We always wonder: Who is the person recording? Was it one of your teachers?

MES Exactly, she taught at the art school I attended. Gilda was amazing. She was a painter, and she took these really frank and confrontational videos of just about every exhibition that opened in the Detroit area. It was heavy to look at it now. It moves in so many directions, not only personal. With distance I can see so much that drives me still today.

LAC If you don’t know, you might think she’s a random American tourist entering a gallery and saying, “Oh my God, this is Michael Smith, and why the fuck is there a fucking fridge?” But in reality, it’s much more than that, and the video feels like pure intellectual love delivered without restriction.

I must admit, I’m also obsessed with gallery space in general — that Susanne Hilberry Gallery specifically felt like an American gallery outside of New York, outside of the market system. It really seems like a theoretical merge between Elephant (2003) by Gus Van Sant and extreme art. Do you have any memories of what it was like to install the show and relate to that gallery space?

MES Susanne was wonderful. I loved her and the gallery. The walls were sanded plaster rather than painted drywall. They had this cool smooth touch and looked like clouds. I usually don’t spend much time in the cities where I work. In this case we lived two blocks away, so I was around often and understood the space blind. And Susanne and I were tight, I miss her. She passed away in 2015, six years after that YouTube video.

The gallery was in a very odd location. I rarely do site visits because topical information and details seem to just make trouble. And this is one of those cases where I know where the gallery lies geographically within the city, and what that means, and how people use it — what worlds are connected within it. That’s what I like about Detroit. I love mixing worlds, and that’s part of the reason why I’ve never wanted to live in an art center. I love being a weirdo with my neighbors and just being with every kind of folk.

LAC I don’t think Susanne’s gallery is replicable. I don’t think there will be any other spaces like that, unless some mad guy decides to open something divergent. But it won’t fall through, we’ve been brainwashed. I feel like there’s no more time or space for new gallery architecture, nor for openness or for other modes of operation.

MES I remember Susanne apologizing on different occasions — in a kind of joking way — for not doing art fairs. She couldn’t stand them. And I remember thinking, “That’s why we love working here with you.” I don’t know how she made it work, but the pace and the speed there was, even twenty years ago, it was slow for its time. And then fast as well on other levels — dynamics and distances were opened that I’ve yet to experience anywhere else.

LAC I was trying to read articles about you, but they were all disappointing to me. I’ve been lucky enough to see two of your exhibitions, and I don’t think an article or a book is enough to describe your work. Even photographic documentation freezes the practice into an area where it become mood board–friendly, and a commodity to use by any other discipline without any real intellectual interaction other than the visual edginess of the pieces. I really dislike the texts that have been written about you because they always use adjectives like “haunting” or “ghostly” to describe your work, and I think they simply don’t match with what you do.

MES I knew I had a choice to either chase control everywhere or just let it be and just quickly see what happened. Well, it’s so basic and so silly at times that it’s just perfect. Then it’s like nothing’s been written.

LAC In these texts, there’s this obsession that you are somehow about haunting things. You are a verb, kind of a derivate of a poltergeist. I know people do things in rebellion to a space or in rebellion to the status quo. Yet the work is always so poetic and precise that it is also very dirty and complex. I’ve been sort of an insomniac lately, so one day I decided to watch your interview for the Henry Moore Foundation, where you had an exhibition last year, and I sort of felt that everything was so perfect that you hated what you were doing.

In relation to that exhibition, and also to Henry Moore, I think it was a perfect reflection on American sculpture, and that was necessary. Nevertheless, I felt that it was so staged that there was nothing for you to rebel against specifically.

MES Weirdly, this is something I’ve noticed just recently, because in the past, my relationship to even doing an exhibition was so charged and I would communicate very little, mostly because I felt like I was doing something impossible. My allegiance has always been bonding with what I’m doing. I chased the impossibility of making good art rather than the possibility of making money. So that experience was always charged on a practical level; my relationship with the institution and the curator would at times feel like I was sneaking in and out, like I had to really protect my gravity. As time progressed, I’ve gotten better, at least in articulating the grounds and how history starts to add up, which becomes a different problem. The collaboration with Henry Moore was unique, like they all are – so many variables. I mean, I really do improvise, and this alone opens a range. I research and push on materials and ideas relentlessly in the lead up so there is an odd ground that’s intelligent, structured in a way. And then I work from this on site. I rarely feel like it’s nailed. You get to a stalemate sometimes. To me, it just feels like if there’s a fight, it’s a fight to have a moment that’s not sleeping. That’s not easy to do; not with an art audience, and definitely not with the general public. A lot of times that fight is to try to keep believing in what I’m doing, even in practical terms — that there’s a way that this could be special.

LAC I noticed how you always talk indirectly about your work, as your sculptures and pieces are contingent to specific yet casual formats of upcycling and salvaged material research. There is, nevertheless, a very stringent and quite beautifully dramatic edge to it. It makes me reflect on American culture at large. What part of American culture is haunting you?

MES It’s all of it. It’s a given, specifically now that it’s easy to recognize. But I think at all times that would be my position. I’m quite universal about it in that way where I just try to make room for anything that’s happening. I do a lot of day-to-day research, current events, and small tangents just to try to keep a hold on that. But I think who I am shapes that without my control.

LAC I think that your art feels current in a way that I don’t have to look at CNN to be scared or touched by a full political and visual spectrum. But I can feel in it fear, danger, and accompanying scary thoughts in ways that are not directly speaking about that. But it feels current.

MES The biggest part of what I do is paying attention; that’s it all the time on a very small level, on a casual level. I don’t try to make large sense of it. I just try to follow, and this is intuitive as well. I never rest, I’m always nervous because I always have four or five lines going into relationships and situations with people that cover a large ground. It’s not unlike anyone else, I just try to prioritize that level of experience and sensation and research as often as possible. And that’s what is afforded to me: if I had to work a normal job, then I’d want to just relax. Paying attention is a full-time job, and at this point it’s on an emotional level because there’s no real sense or logic that could help me to start to try to make sense of what is happening. I think I try to pay attention through working, and I don’t know how to talk about it. It’s like allowing the build-up of so many moments and the madness of that, and then you start coming out a weird shade.

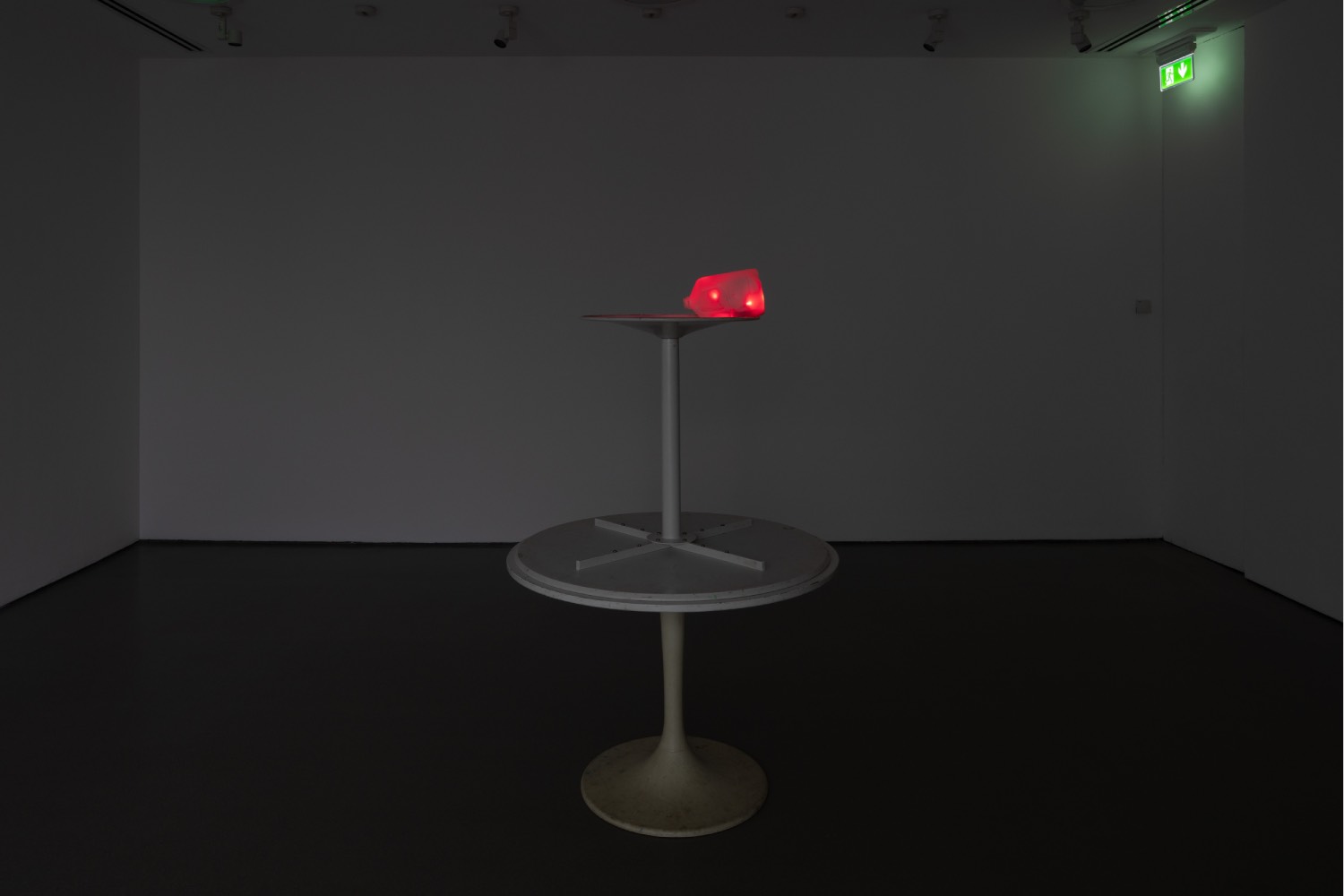

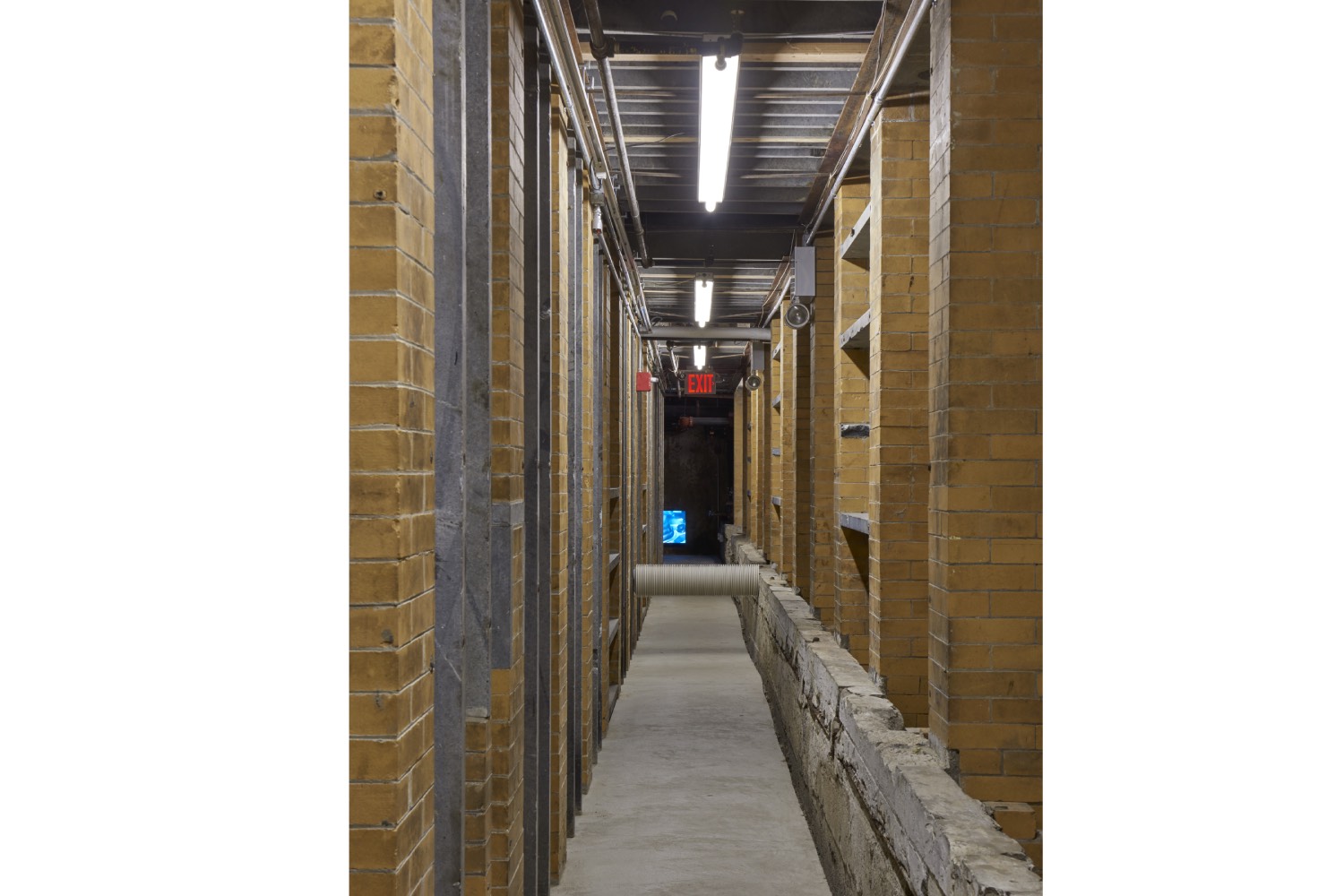

LAC Keeping it strictly to your work and the resonance of it, I was incredibly taken by a small sculpture you exhibited at SculptureCenter, New York. There was a small podium and a stuffed cat sat under a silicon mask. It was daunting, and it was exhibited in a corridor in what I think is the underground of the space. I won’t say it touched themes belonging to American horror cinematic tropes.

MES I’m actually kind of squeamish, and I tend to only use moving pictures for sedative purposes. I watch King of the Hill or Bob’s Burgers. My children are really obsessed with anime, so I watch a lot with them.

LAC What are your interests outside of making art? Did you have a specific musical upbringing growing up in Detroit?

MES Yes, I grew up with music; everyone did, that’s why I like it I’m sure. It’s completely across the board. I have a fascination with specific artists at times and enjoy tough music. I collect records. I grew up on hip-hop, and that was the only real art experience I had growing up, before I started making visual art. I think my relationship to music is the reason I work the way I do. The way I experience meaning and time when I’m working or listening. I envy musicians. I do make music, but I’m not trained, and keep it free. We have horns, drums, guitars, electronics. I’ve been in bands in the past — I like communicating that way. I remember when my children were younger, music was the one place we’re equal, and we would just be together and it’s like none of us are trained at all. But when you would find something together, that kind of communication with your children or someone else – it’s an incredible experience to link that way.

LAC What about your exhibition at SculptureCenter in New York in 2015?

MES That was a tough one. You could almost imagine the entire basement of SculptureCenter like a giant battery. It had insulators so that massive amounts of power could travel through it, and it was laid out and designed in small chambers. That’s why you get those skinny corridors, because it worked more like a power center than a place people navigated.

LAC I felt that space was too literal for your exhibition.

MES It just has so much content already. I had no choice but to go with the way you move through the corridors, and you get lost in it easily. It was quite easy once I found the direction that I was going with it. The work you mentioned with the latex mask — the mask was on the head of a black Lab. It came from a small natural history museum. I bought it impulsively and it sat in the studio for a couple of years. I didn’t think I would ever be able to find a solution for something so powerful and bizarre. I remember casually placing the mask on the dog and it balanced perfectly. The mask came from an old chain of restaurants in Michigan called “Big Boy,” and the restaurant had a giant pink man-child as a mascot.

LAC You remade the mask?

MES No, the mask was from the original franchise I assume. It is almost like a crude latex positive to a mold.

LAC What kind of work do you put in an object? Is it fixed? The mask on the Labrador is structurally holding itself. If a sculpture is already sculpted, do you act as a sculptor?

MES I do whatever is needed. If it’s good, if I’m turned on by it. I’ll get detailed with an airbrush to get a proper patina on an old bolt to match the vocabulary. We can get very precise and neurotic about a specific line we are following. But those are dictated by ideas. It’s an ethics I think that drives me. Some ridiculous notion of doing this and feeling good about it still, and then you just end up in a place that’s incredibly open and flexible. There are a few projects I’m working on right now that are different and outside of what I normally do that I’m super excited about. But beyond that, the way the spaces look and how they operate, that’s a challenge. How to continue to give something to somebody that hopefully they could pick up on and feel good about. I hear myself say these things and realize that if I don’t reduce it to that basic dynamic, then I’d be doing a disservice to the work to speak to any specific dimension aside from just contending. How much of that process is just a given? And then I started to realize that, to a certain degree, what I was doing was fairly unique. The majority of what I do is in an editing process more than an assertion. There are specific trains of thought. What would a person with absolutely no art history read from this if they were just paying attention to what they’re seeing? And how does that sync with other levels of understanding? And that’s maybe the place that I work on a craft, in a subtractive process. Thinking of making something good, I rather try to not make something bad, which is very different approach. It sounds like a clever line. I can recognize what’s not working and eventually this leads to something. I don’t know. I’m still stretching to say something I believe.

LAC I have one last question, mainly just for me. What’s the last book you bought that I should read? (Cheesiest question of all time.)

MES The last book that I read is a book about jazz. It might not be something you should read. It’s a book about the work of Anthony Braxton, Forces in Motion.

LAC I have an affection for a CD I got back in high school: Black Vomit (2005) by Wolf Eyes and Anthony Braxton. I think I gave the CD to a pure jazz lover as a joke present.

MES https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0o0AYFRFX7g