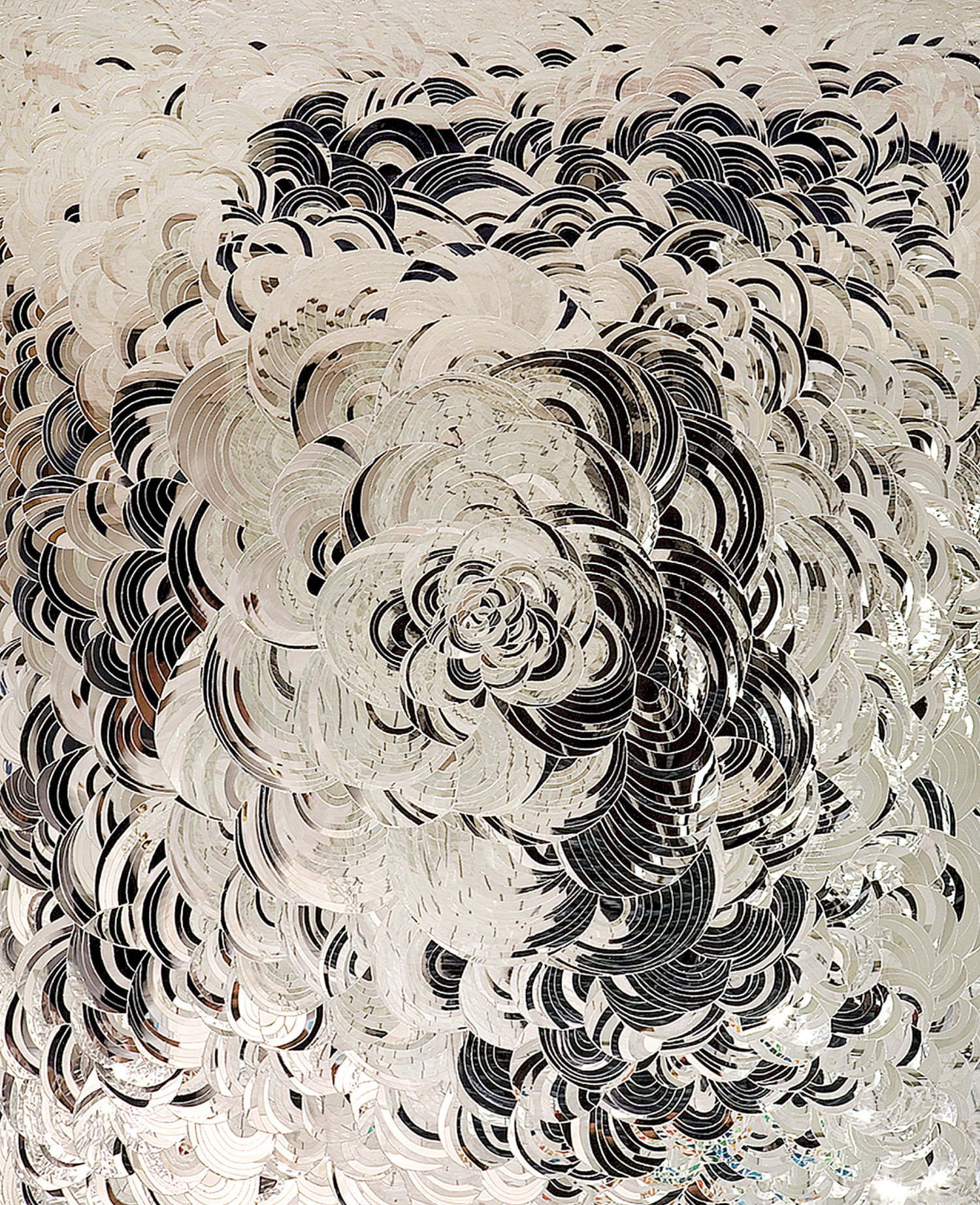

As a child, one of my toys was a tape recorder. After my father had bought and grown tired of the machine, he let me keep it in my room. Haphazardly touching this strange device, I became interested in the various ways the sound changed. If you sped up the tape, the sound had a higher pitch, and by reversing the tape, you could create strange clusters of sound. By cutting the tape into pieces with scissors and putting it back together at will with adhesive tape, you could construct sound. And by connecting the ends of a piece of tape and making a loop out of it, you could make a pattern of sound repeat infinitely. To me, making music was a graphical act of cutting and pasting with scissors and tape.

In 1913, several years after Einstein had argued that time and space were inseparable entities in his special theory of relativity, Stravinsky caused a riot in Paris with the first performance of The Rite of Spring. The following month in Milan, the Futurist painter Luigi Russolo held a concert featuring a noise-generating instrument he had made called the Intonarumori, and that fall, Marcel Duchamp had used a chance system to create a composition called Erratum Musical, a musical version of his sculpture 3 Standard Stoppages. Painters were beginning to make music.

At the same time, in the world of music, Arnold Schönberg developed the “twelve-tone technique” by arranging the twelve tones of the octave into a basic melodic pattern and then inverting the temporal and frequency axes in a mirror-like reflection of the original to create four patterns, which he then committed to a musical score. It was truly a graphical method of composition. Composers were beginning to make music as if they were painting pictures.

With techniques such as reversing, expanding and contracting, repeating and randomizing patterns, you could create music that opened up whole new worlds. The problem was how to deal with space. Boldly setting out to solve this problem, Karlheinz Stockhausen devised the concept of “spatial music,” in which he supplemented the four elements that made up conventional music — pitch, intensity, duration and timbre — with space. Focusing on aspects such as the places where sound is emitted and spatial shifts, Stockhausen argued that space was an essential part of musical composition, which until that point had only been developed along temporal lines. He stressed that the addition of this new element would also necessitate a new form of listening. In the ’60s, Stockhausen recorded a lecture on spatial music for NHK, Japan’s national public broadcasting service, in which he said the following:

“The way that concerts are given will also change. In spaces like this, music without beginning or end will be performed continuously, allowing anyone to stop by whenever they want to and listen only to music in a space and time of their own choosing. There is nothing new about this. Exhibition venues showing contemporary art are actually the same. People can go from one room to another as they please and gaze at their favorite pictures as long as they like regardless of whether there is anyone else there or not.”

I read a transcript of this lecture a few years ago. It made me realize that what I was trying to do was to put Stockhausen’s remarks into practice. Having first entered the world of music using a tape recorder as a toy, I have now stepped inside an even more wondrous world of music with another toy, the music box.