Maurizio Cattelan: Hello Matthew? Is that you? The phone signal is very bad. Is this a good time for some questions?

Matthew Monahan: I’m sure we’ll be cut off. I must be in the middle of nowhere or something. Anyway I hear an echo in the phone and it’s driving me crazy.

MC: And it sounds like you’re talking through a mask! How do I know it’s really you and not one of your imposters?

MM: My imposters? You must mean my sculptures. They don’t do interviews, though their story is more interesting than mine.

MC: What is their story?

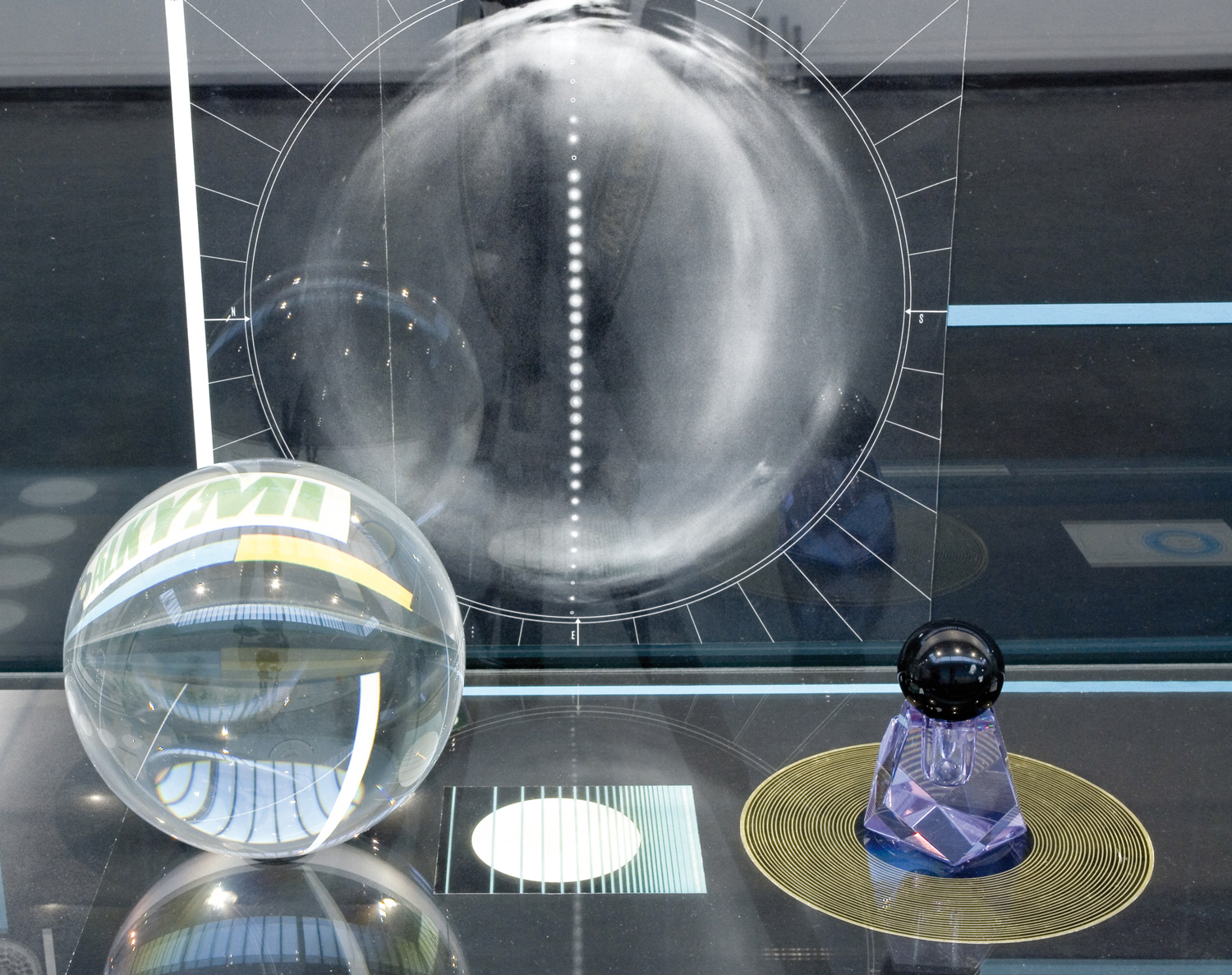

MM: “Well, today I had my eyes gouged out, and my forehead cut off!” And they might say: “I was born a god and now I live on skid row. I came out of the block, smooth and beautiful, symmetrical and defined, ornamental and manneristic. I was anointed with pure beeswax. I was adorned with gold, embellished with glitter and rare pigments. I cast the imperious gaze of the pharaohs.”

MC: I can still hear you but it’s choppy.

MM: “…Exactly! I was chopped up too because I was useless among the atheists, and I was castrated by the pious! I fell from a great height, got hacked up for spare parts, made into cannon balls and foot soldiers, camouflaged for the Iron Age! Smothered in graphite, armored with nails and angular geometry.”

MC: I can’t understand you very well. Can you call me back on another line?

MM: “The avant-garde sent me off to the front lines! To be annihilated for the cause, for progress! Abstraction! Autonomy! All I got was sent home in a box, stuffed with trophies, a hero’s welcome. Now I am just army surplus, a scarecrow, blasted from the past, a curiosity…” Can you still hear me? I’ve lost you now… let’s try later.

MC: …Hello, it sounds good now, where are you?

MM: I’m in my new studio. The signal here is very clear. It’s downtown at the intersection of the toy district and skid row. I just saw three grown men drop out of a tree with a bouquet of flowers. There are strange dances going on under that tree, symmetrical gestures — must be crackhead prayers. And the roots are all smooth from the circle of squatters that hang out between patrols. But the tree makes it seem sort of picturesque and peaceful.

MC: Are you at home with the homeless?

MM: Well, it’s a bit scary at night outside the compound, all the tents and boxes come out and people are always darting around in front of the car, everyone out in the open. LA is usually vacant and, when you finally see people, they sleep on the street. Working out existence right in the open. It’s a full-time job. There is a lot of waiting around, looking busy and keeping your shit together, changing corners. The nervous system is in overdrive and it’s just burning through all these bodies. And on the other side of me the toy district is wall-to-wall discount stuff from China. I am in the middle of it with a whole factory for myself, manufacturing my own ego. Hideous offspring! Yesterday I made a sculpture that looks like a model of a street corner, crumpled heads laying around, so this place is already having an influence.

MC: Is your studio very important to you?

MM: Mostly, I have no ideas for work without the studio. In fact I have a pretty poor imagination for art. I can never execute a plan; I have to have my hands in it to find my way, and they do their own things most of time. I have a few rules but then I attack the subject with every method I know. After a few hundred faces you just want to crack open the face formula and get more out of it. Some days I’m sure I’m beating a dead horse!

MC: Is it a problem of re-animation?

MM: Yes, but it’s also interesting to see how inanimate the figure can be, how figurative art dies, how it scars, how it shatters into mere things, how it turns to dust, because these things still resonate, they still have a pulse. That story — that aftermath — seems endless. There are moments when the face really comes alive and the body seems to twist of its own volition, when the figure comes at you, but I seem to go out of my way to ruin it, to push the gaze back inward and paralyze the body as if caught in the rigidity of a trance.

MC: But you stay with the dead horse?

MM: I have tried to leave the figure behind. Sometimes I can’t stand all those demanding characters. Doing landscapes I thought I could lose the figure out in the desert. I thought I could become abstract, but it was no use. Without the figure the whole thing becomes arbitrary; I seem to lose the pathos and poetry. And so I’ve learned all kinds of other ways to distract myself from the demanding characters, to break their symmetry, and give them props and stages to keep them busy. But at the same time I don’t really want to tell a story or make a scene. I don’t want to make them sing and dance. Place and time have to be compressed and buried within the figure itself.

MC: You mentioned you have rules in the studio.

MM: No use of photography, no projections, no mannequins, no live models, no body casts, no ready-mades, no fabricators and no source material. I am pretty dogmatic about this. When I stared with figurative work in 1995 it was so hard to concentrate I had to make sure I had no short cuts out of it. It seemed like an ‘anything goes’ time in art and I felt that I had effectively dropped out.

Charcoal drawing? How uncool is that? I just wanted see something that only I could make, and I thought I could find it somewhere in the face and in the body. If you fix the rules and the subject matter, you can really concentrate on the development of style, and by style I don’t mean fashion, I mean it like Barthes when he called style that “lonely and vertical dimension of thought, the product of a thrust and not an intention.” The loneliness could have been too much but I was in a kind of gang with two other artists, Tom Houseago and Micheal Kirkham. We called ourselves “the crows,” and we really stuck to this dogma and supported each other in our new figurative adventure. Otherwise I think it would have been impossible.

MC: Your were in Europe for a long time and then New York and Los Angeles. I saw your work around here and there but then you had a show at Anton Kern in 2005 and suddenly it was all there. You exploded all at once. What happened to you?

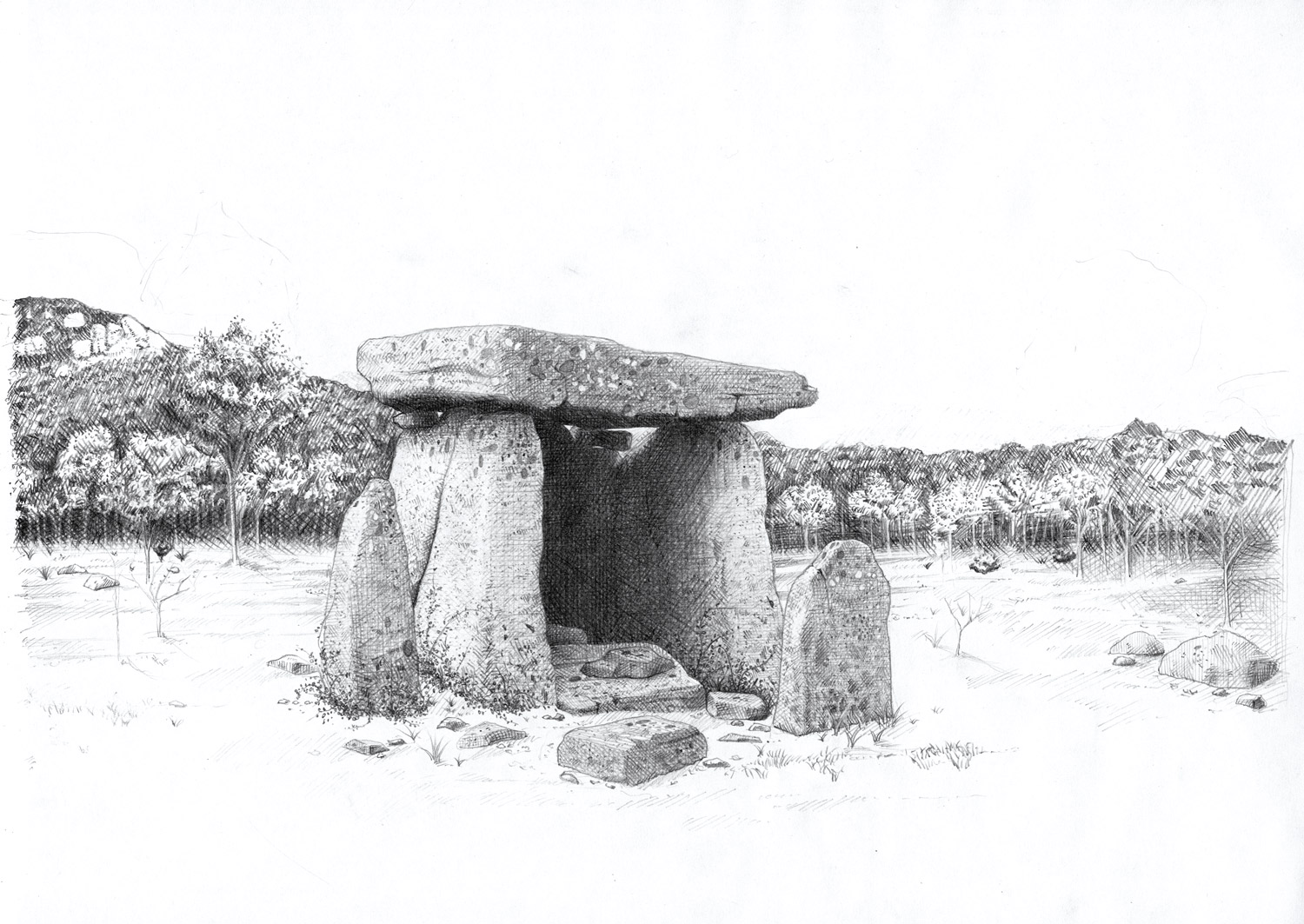

MM: I was tired of the here and there, and with all the traveling the work was getting split up in series and I was losing focus. I dropped out for a year and went back to the drawing board, charcoal on paper, and I reconnected with the early work, old professors, and finally it really made the circle complete. I did make one trip that year to Tibet and Nepal which had a huge impact on me because sculpture is really used there to house spirits, and there is a freaky kind of idolatry. I came back and then Bush got re-elected and my bleeding-heart liberalism just gave out completely. I switched from NPR [National Public Radio] to Indie, I couldn’t stand that monotonous stream of ‘impartiality.’ And I realized that if I have any power in this world at all it is through art; even if it’s dark power, or absurd power, or sad solitude, it is still power. So I just started grinding through everything I ever made, every technique piled high, all my unfinished business, and I loaded up every misguided missile and un-detonated shell I could muster and just put it all out there, the whole stockpile: a sprawling, makeshift shantytown of sculpture and drawing.

MC: What about all these pedestals? I get the feeling that the curiosity cabinet can’t contain you anymore.

MM: The pedestals are my concession to the real world. They are like a middleman, a dealer, to stop the work from getting stepped on. I am not ready to do away with them just like I’m not ready to leave the white cube. I thought that making things bigger would make pedestals obsolete, but I actually like the propriety and alienation they create. I don’t want to bridge the gap with art and life. I want to sustain it, like a tragedy all its own. They are remote and incomplete and need a careful observer. But I want to increase the tension between the pedestal and figure. It can be a very inventive and testy relationship, something like a master-slave dialectic. I think the curiosity cabinet thing has been overstated. It breeds some kind of colonial detachment that I want to break. You build a bridge to the beyond and everyone see just sees the bridge. Maybe I am not ready to cross the bridge. When I do shows I am always caught off guard by the exhibition space, all the secrecy is lost, like when the song stops and everyone in the room can hear you shouting. I wish I could crumple and fold up rooms like I do with paper. Where is Gordon Matta-Clark right now?

MC: You are a good mimic, you could be Gordon Matta-Clark.

MM: I am a lot of artists! I channel everybody into some garbled incantation. I feel like art history is full of all these amazing potions and magic spells and illusions. With all our modernist purity and American progress everything got taken from us, made into a useless art history class? If you are stupid enough to call yourself an artist you might as well get the keys to the medicine chest.

MC: What is next?

MM: Aside from a new solo show, I am working on an outdoor piece for Sonsbeek, in Arnhem, the Netherlands. All the work is going to be displayed in the park and then carried through the streets in a procession like a holy relic. That will be a new pedestal problem, a pedestal made of people. I might have to channel Maurizio Cattelan for that one.

MC: Why don’t just go out and beat your dead horse?

MM: Hi-Ho Silver, to the rescue!