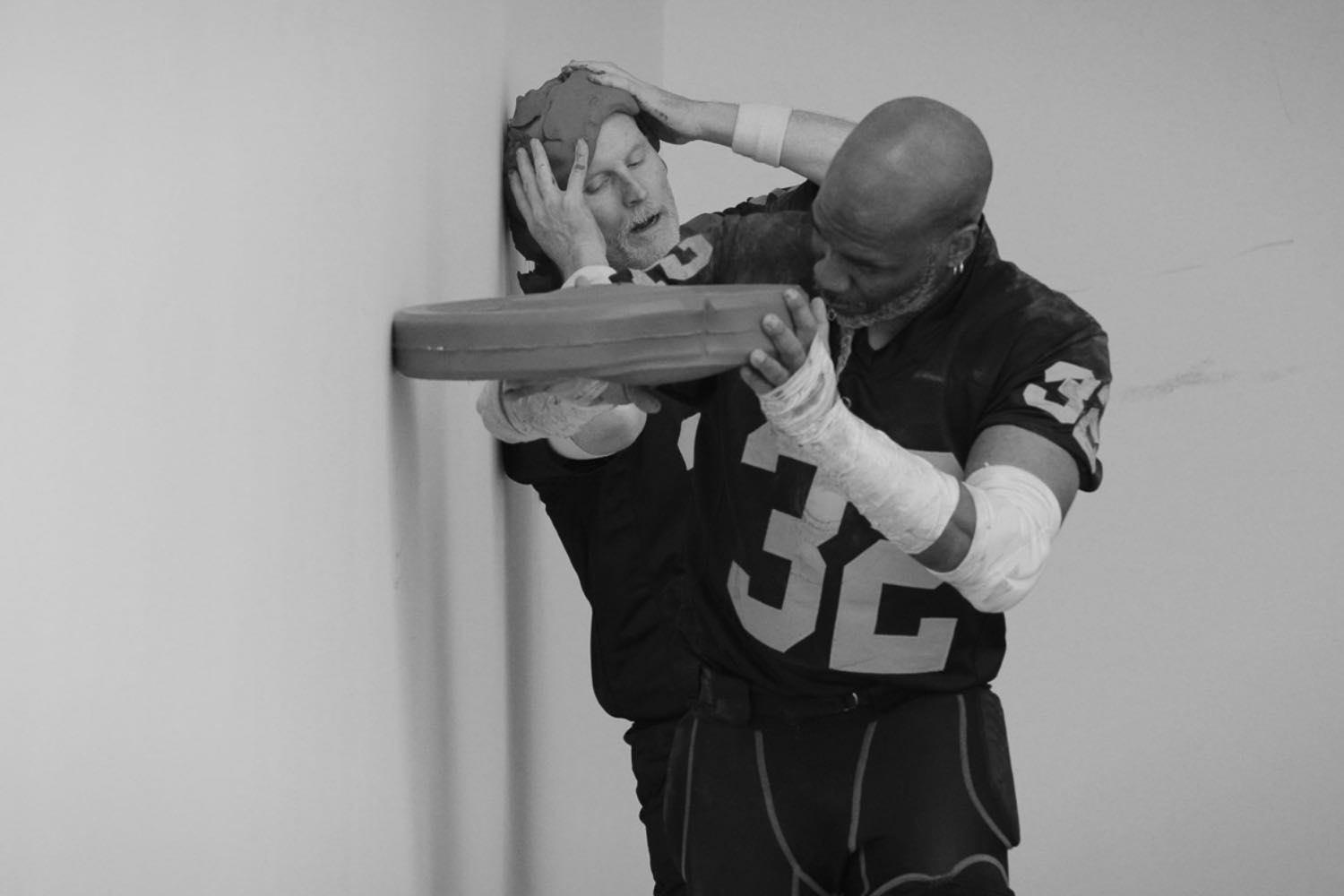

Matthew Barney’s latest film, Secondary (2023), builds to a single moment — a balletic reenactment of the infamous 1978 American football tackle, when Jack Tatum hit Darryl Stingley hard enough to break his neck. In Secondary, as in life, this instant of violence transforms both players into metaphors: one of them a victim, the other an unrepentant assassin. Football is a pantomime of war, complete with generals, strategy, tactics, and drills. The dancers wearing Raiders and Patriots jerseys in Barney’s film are mostly graying, well over the age a body can withstand the strains and shocks of football. It seems like a strong hit could break them. But they’re not really playing football. There are no balls and very little contact between the players, until the final showdown. Instead, they perform exaggerated, poeticized evocations of the game’s movements, as if swimming through thick layers of memory.

Barney, a former football player himself, is known for his work’s physicality. He’s scaled the Guggenheim rotunda in Cremaster 3 (2002) and made drawings while hanging from slings in his Drawing Restraints (2005), phrasing art as a contest of both brain and brawn. His latest work seems to return to this theme — yet Secondary is less about physical strength or struggle than points of contact. The focus is the interface. Like the two players’ impact transmuted into a lump of clay, the sculptures related to Secondary carry the idea of interfaces in their materials. A net made of cast barbells — lowered funereally into a muddy pit in the film — consists of pieces in the three materials that characterize the suite. Not only are plastic barbells linked to aluminum ones, but individual weights are made of two contrasting materials wedded together in unnatural junctures. Sanguine Atlas (2024), for example, features a net of linked barbells that transitions from plastic to two shades of ceramic. Several of the pieces are half plastic, half clay, and must have been cast in two stages, although the junctures are fairly seamless. Another piece, impact BOLUS (2024), includes chains of barbells cast in combinations of aluminum, pewter, and lead. These split weights are single objects, composed of two halves, part of a larger fabric. In a way it’s the material integrity of objects that makes them strong. A joint between two unlike materials is a potential break.

There are many other portentous junctions in Barney’s latest work: in a new series of ceramic sculptures based on weightlifting racks, composed of multiple independently cast pieces fitted together; in wall-based weight rack sculptures in which cast ceramic round weights are hung on reenforced ceramic pegs. The matte red clay conveys a sense of vulnerability, brittleness, like an ageing athlete, maybe, or like the grizzled team manager who stirs the cauldron of molten metal in Secondary. Art and sports are young men’s games. Eventually, the body’s infrastructure starts to fail. In the film, a broken water main fills a pit with mud. A related sculpture titled Supine Axis (2024) consists of a six-meter section of red ceramic pipe crumbling into rubble in the middle. Along its length is a spindly white plastic armature that resembles the steel orthopedic braces used to set fractured bones and spines.

For all the staccato action of the sport, Barney’s film dwells in anticipation, quiet, practice. It takes almost the film’s whole hour for the hit to happen. The tension builds. We see dancers in football gear, rehearsing in what looks like a large, resonant casting studio, doing graceful jukes and scuttles, hurling handfuls of transparent goo at crowded warehouse shelves, tackling full trash cans. In one sequence, the dancer playing Tatum swoops at a sheet of wet clay, folds it around his arm, and sets it in a wooden cradle to dry, all in one fluid movement that resembles easing a body to the floor. The camera, too, moves with deliberate grace. It’s as if the pacing parallels the reality of artistic process. Characters stir a cauldron of liquid aluminum and tend a kiln with careful, unspectacular movements. Football is spectacle, and Barney’s previous films indulged in spectacle, overwrought visuals, hypercolor, and heroism. Several entries in the Cremaster Cycle (1994–2002) specifically stage sporting events. But not here. Secondary is a studious glide to the finish, marked by waiting and method.

Bones might heal, but ceramics won’t. In the Bible, as in other world creation myths, the first man is made from clay; ceramics retain the connotation of the human body, the strength and fragility of a human life, and the fundamental irreversibility of death. Once a clay vessel breaks, it can’t be repaired. It may carry on as a symbol but it will never be whole again.Tatum and Stingley are bound together in an erotic pas-de-deux — by circumstance, by chance — and also by the design of their roles on offense and defense. Their contact is the collision of big forces, transmuted into sports. In the film, their collision forges a physical shape. Barney debuted the Secondary works this past fall in spectacular fashion, with simultaneous shows in Paris, London, Los Angeles, and (without the film) New York; several sculptures included variations on the form created by the negative space between their bodies at the moment of contact. It’s a cast of a void. Barney permuted the cast in the trio of substances that give his latest body of work its character: unglazed red clay, aluminum, and plastic. He lets some casts slump, unclamping the mold before the materials set completely. In the film’s climax, when the two players finally collide, they produce a trio of lumpen casts of the negative space between their bodies — these fall to the floor, one after the other: a white rubber, a soft aluminum-colored cast, then one of clay. The last one shatters, in slow motion, a pianissimo spray of shrapnel.

Barney’s previous work plays with dualities, in particular the ubiquitous symbolism of male and female that compels the Cremaster Cycle. The new work pivots around a dualistic structure — two teams, two men — yet it’s more open and confused. The environment of the football field and its training facilities is a homosocial one. Some of the referees and Raiders fans are female-presenting, but the football players are necessarily male. Football is a homosocial space, and a team is a heterotopia — a social enclosure, where members are bound to their brothers-in-arms by laws and codes, loyalty, a cause. In the United States, football also channels battles in the civil culture war, for example over protesting the national anthem or what liberal pop stars are in the stands. Questions of male (hetero)sexuality are particularly acute. As of this writing, no openly gay athlete has played in the NFL regular season. Yet Barney’s vision of pro football circles around the anality of ruptured pipes and pits of mud, and the contact between men is gentle, choreographed. Before the final match, a two-spirit singer performs the US national anthem, abstracted into peeps, chokes, and laughter — the song is recognizably “The Star-Spangled Banner,” but just barely — and the only word they enunciate is “bombs, bombs, bombs…”

The story of American football is masculine violence, mitigated. The sport is often compared to gladiatorial contests, a sanitized and regulated spectacle of combat. This belligerence is underscored by the explosive graphics and sounds effects of an NFL broadcast, and by the aggressive avatars of the teams. In particular, the two teams in Secondary, the Raiders and the Patriots, symbolize the two unified aspects of this all-American sport, its spectacular violence and its power as part of a national identity. From its invention in the late nineteenth century at Ivy League colleges, football has been nakedly discussed as a barely contained rehearsal of combat. There’s glory to be won on the gridiron, but there’s also deadly risk. In the early days of the sport, it wasn’t unusual for players to collapse on the field. In 1904, for example, eighteen players died. The gray-haired Raiders player Barney plays in the film takes the pads from inside a helmet and tapes them around his head, making something resembling the leather headgear players once wore for protection. He falls to the ground, as if laid out by an invisible defender, and the thud echoes in the warehouse.

Instead of the glory and strength one might expect in feats of weightlifting and city building, Barney’s new work describes a sensitive sort of male vulnerability. The film draws out football’s (and war’s) heavy symbolism of sacrifice, even unto death, wherein virility and violence curve around to total limpness, the injured player or wounded soldier carried off the field like Christ in the pietà. Here is grace and receptiveness, not hard hits and penetrating drives. Toward the end of the film, while Tatum and Stingley near their fateful moment of contact, another player begins lowering himself into a grave-shaped hole cut in the concrete floor of a warehouse. Water from the broken pipe has turned it into a muddy bath. He grips the sides of the pit and lowers himself into the water, slowly, deliberately, with a basically tantric degree of control. The scene evokes the “wet soldier” genre of erotic videos, in which young men in army clothes slowly lower themselves into full bathtubs. Anticipation of the inevitable, savoring the possible break.

And the film offers sensual delights, particularly its crinkling, squishing soundscape. The percussive thuds, claps, and grunts of the players resonate in the waterfront warehouses, and the water laps gently on the wharf. This is a soundtrack of subtler contacts, the sound of clay or polymer or metal impacted by flesh or architecture, the farting of mud and trickling of wastewater, with various degrees of violence.