Let’s be clear, it’s not about the color of the skin. Even if I have to admit I have never seen in the history of painting such a wide palette of colors for the surface of the naked human body as I have seen in the paintings of Marlene Dumas. Titian, Rubens, Delacroix, they all showed that the color of the skin in painting can take a full range of blues, reds and greens. But such wonderful, washed out, transparent colors of dark red-brown, deep purple-blue and variations of charcoal on a living body, and such frightful tones of whitish green and bluish mist on a dead body or face, make Marlene Dumas an exceptional painter. But let’s not judge by the color of the skin. We should look at the character of her paintings.

In an earlier series like “Black Drawings” (1991-1992), 111 small-format, ink-and-watercolor drawings, the typical ‘white’ viewer may not succeed in identifying anyone. Black is black? What we clearly see and have to admit is that they do not all look the same. Fair-minded, we are still deeply indebted to the whole black continent to go through such lessons, even today.

“Models” (1994) is a similar large group of 100 portraits. You can read that these are based on well-known faces from the worlds of fashion and media, but it’s difficult to recognize who’s who. The whole group is a true mix of all races, styles and facial expressions; even a snake’s head appears to apply for the job of model. But what’s more important is to look in detail at how Marlene Dumas employs all the coincidences, to let it simply happen that lips, eyebrows and hairline emerge from the fluid ink. Painting requires time — a lot of time — to look and to decide, to add a small blue line for the nearly closed eyes here, some light green there to create a mysterious glance. Over the years Dumas has developed unique painterly skills. She knows how to do a painting with what looks like just a few brushstrokes. Fingers (1999) is a demonstration of such effortlessness.

Let’s be clear; it’s not about sex either. Even if I have to admit I have rarely seen in the history of painting such erotic, hot girls and gestures as I have seen in the paintings of Marlene Dumas. Goya, Toulouse-Lautrec, Matisse, Picasso, they all showed that a painting can radiate a full range of seductive meanings. But such an open approach to the visual game of sexual promises makes Marlene Dumas an outstanding contemporary artist. Pornographic imagery has penetrated our societies to the core. There are possibly more images showing humans in all sorts of sexual activity than there are in actuality. Isn’t that frightening? Shouldn’t somebody try to make something positive out of it?

All the works Marlene Dumas has created from this immense well of pornographic images have one leitmotif in common. Her paintings leave the pornographic dead-end street behind, which only leads from one perversion — which becomes mainstream — to the next one, and, instead of depicting everything in the deadness of painstaking precision, the paintings reinvest sexually explicit imagery with an element of secrecy and promise. They return to the field of eroticism and desire.

At her exhibition “All Is Fair in Love and War” at Jack Tilton/Anna Kustera Gallery in New York in 2001, paintings like Aurora, Stella or Electra (2000-01) depicted scantily clad women behind a grid structure. Playing with the notion of window shopping for Amsterdam prostitutes, Marlene Dumas leaves it to us, the viewer, to decide who may be in prison and who’s not, where love ends and war begins, and on which side of the bars we think we are standing. But the paintings are more than just a game with the viewer. They withdraw these women from anonymity and create identity and immortality within a field of complete namelessness.

Death is no respecter of persons. We say death makes us all equal, but this does not indicate that the dead lose their human dignity and grace in the eyes of the people who loved them. Mass media show us hundreds of dead from war, disaster and plague, perished by accident, by crime, by terrorist attack. We are used to their appearance in press photos and news coverage. They merely illustrate the horror. Mass media loot the dignity of the murdered and slaughtered. Doesn’t someone have to restitute grace, dignity and grief?

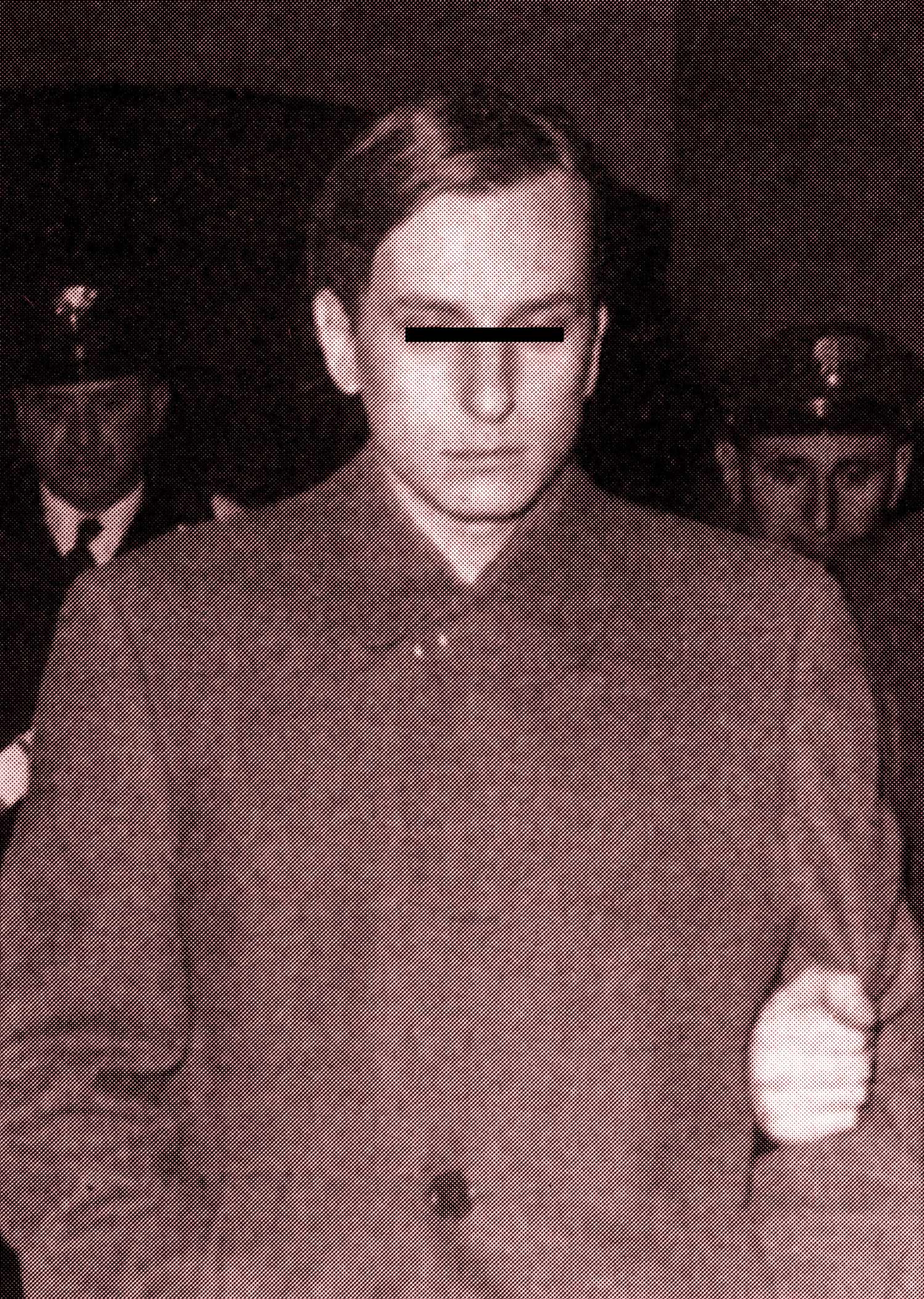

In 1988 Gerhard Richter painted Tote (Dead), 1988, part of his cycle of works “18. Oktober 1977.” Based on a photograph, it depicts the dead Ulrike Meinhof, founder of the Baader Meinhof Group, who had killed herself in prison. The original photo depicting the head of the woman who committed suicide was published in the German magazine Stern, and was also proof of the victory of the German Republic over the militant group, who wanted to destroy the state for a dream of a different society. A dream that became perverted and found its end in death. It seems that Richter’s painting is able to restitute dignity to the dead person, which enables us to feel grief and to forget revenge. There is no feeling of triumph left, no jumping around on the dead body of the enemy, but instead a retrieval of humanity. Marlene Dumas painted the same motif in 2004. The painting, Stern, moves further away from photographic boundaries and suggests additionally something different. It restores the integrity of the dead and the individual beauty of the person. We start to understand that there must have been a mother, loving her daughter, or a lover, a friend, a father. This is surely the case when Marlene Dumas paints from press photos of anonymous deaths, showing immigrants from Africa drowned and washed ashore to coasts in Spain or Southern Italy. Maybe it is important to note that most of her titles do not offer much hint as to the story within her source material. “Stern” means star in English, and I don’t think that the ambivalence implied in such a title is coincidental. For some revolutionary leftist groups in Germany, Ulrike Meinhof was a star.

A star, yes, but different from Marilyn Monroe; her tragic death, revealing the dark shadows of a life in the limelight and the blindness of the male gaze, is still an open account. Dead Marilyn (2008) does not show the sex symbol, but a woman shortly after her life has ended.

We should hear again what she screamed in her last film, Misfits, in the middle of nowhere, to three men hunting mustangs to sell to a dog-food factory: “You’re only happy when you can see something die! Why don’t you kill yourselves and be happy?!”

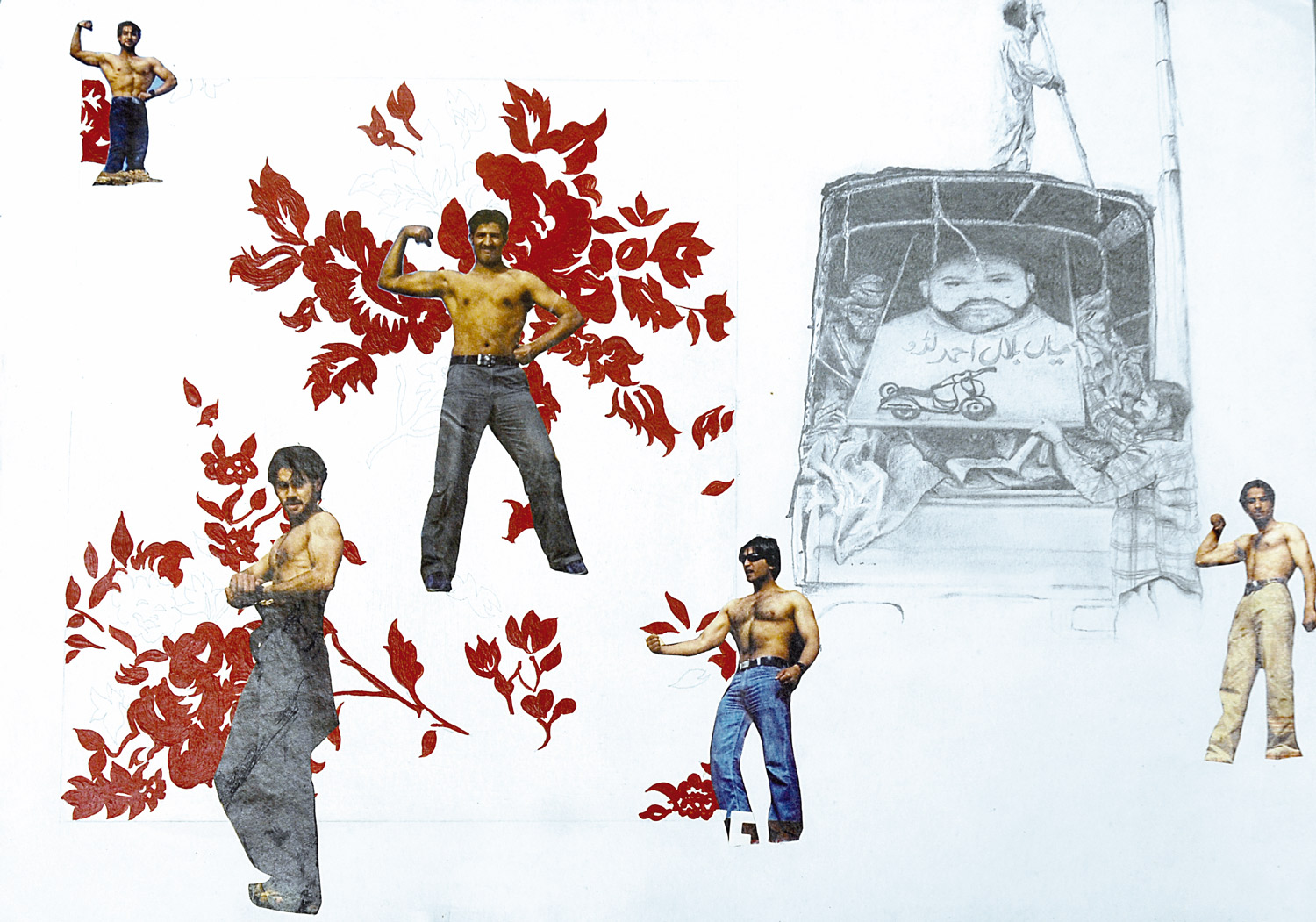

From the middle of the ’70s onward, from when Marlene Dumas, born 1953 in Cape Town, was still in South Africa (which she left in 1978 for Amsterdam), the artist has compiled her personal archives, hundreds of media images, personal snapshots, thumbnail sketches, drawings, Polaroid photographs and notes. Nearly all her paintings and watercolors are derived from these notebooks and are based on a photographic source. All her work rotates around the human body, from the female form to sexuality, pregnancy, babies and childhood, finally bringing into focus the human face, the portrait.

Growing up in South Africa during Apartheid may have instilled some inner resistance to painting the world in black and white. Marlene Dumas’s work opposes a society that simplistically divides good from bad, and it resists political or ideological systems that teach brainless love or hate schemes. We may find the results of such beliefs in paintings like The Pilgrim (2006), The Neighbour or the Look-Alike (both 2005). These portraits of people with seemingly Arabic roots could just as well depict wanted terrorists from some underground army. The pilgrim resembles Osama bin Laden, and you may be able to find look-alikes for the others in the database of any bureau of investigation or counter-terrorist center. Yet as a human being we may have to respect their integrity if we decide to try to live together on this planet and to share its resources.

Without giving a hint as to who is the offender, she paints the victims too: hanged women, Imaginary (2002-03) and blindfolded heads of men, The Blindfolded Man (2007). Duct Tape (2002-05) shows an image we may all have seen on TV and in the press before — the head of a person covered by a sack. But we do not know who these people are. We do not know if they are prisoners or victims of our army and of our war, or if they are prisoners or victims of others, of the supposed enemy.

But we have learned something in the meantime from her art, from the paintings of Marlene Dumas, through their tremendous pleading for humanity. We must find out who they are and what happened to them and who offended them. We must care about it if we wish for human values to persist.

It seems it’s never too late to measure your own grave. You may think you deserve a huge mausoleum and a state funeral. But be honest: in the end you don’t need much more space than all the rest of us. Maybe that is something we should consider for life, too: the need to measure the space we require ourselves, and to start making way for others.