Loneliness lives on our net frontier. Even motherboards and Flash require touch. Think of passion each time you click me into you. E-dream with me before you crash.

–– Ruby, Teknolust

“Born Sexy Yesterday” is a term proposed by Jonathan McIntosh (YouTube alias “Pop Culture Detective”) for a ubiquitous gendered character trope in science fiction. The Born Sexy Yesterday character is instantly recognizable as the wide-eyed, otherworldly alien with a childlike consciousness in a grown woman’s body.

Like Leeloo from Luc Besson’s The Fifth Element (1997): stunning, savant, yet totally inexperienced in the ways of the world; her intelligence may be alien, but her appearance accords with earthbound standards of beauty. And like her indie-movie counterpart, the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, the Born Sexy Yesterday is irresistibly quirky in her strangeness –– a fascinating novelty waiting to be consumed by the (male) love interest she’s inevitably paired with. Often she has a special skill, like combat or computation, but when it comes to social conventions she’s adorably hapless. A succinct tagline for this set of traits may be found in 2010’s Tron Legacy, when the male genius programmer of Cora — an “isomorphic algorithm” in female form — describes her as “profoundly naïve [yet] unimaginably wise.” What could better describe the competing desires projected onto female identity and sexuality? The figure of the Born Sexy Yesterday is rooted in a horror of female agency, of a woman wise and experienced — who’s Born Sexy and knows how to use it.

In her works dating back to the 1960s, Lynn Hershman Leeson (b. 1941, US) has flouted and flipped the urges –– from the mundane to the creepy –– underpinning this fantasy. This entails uncoupling the physical body from the performed identity. For her most famous, originary experiment in inventing or “birthing” new identities, Leeson led a parallel life as a character named Roberta Breitmore from 1973 to 1978. Roberta, distinguished from Leeson by a signature wig and makeup, was an autonomous self with her own apartment, therapist and relationships. Eventually, she was further fractured into multiple Robertas played by others.

In 1996, Roberta manifested again as CybeRoberta, a childlike doll with a webcam peering through hollow eyes. Alongside her “twin” doll Tillie, she streamed images continuously to a website, while remote visitors could control their gaze. Dolls, those ur-avatars for childlike female identity, recur in Leeson’s work. But as technology advances, so does Leeson’s exploration of the avatar, with more recent endeavors such as her Infinity Engine installation (2014) exploiting the possibilities for self-creation afforded by genetic engineering.

If, in an age of AIs and genetic engineering, to be born is to be created, reproduction is in the process of being wrenched from the category of “natural” female (un)labor. Yet when the engineering of life is finally understood as a “cultural” act of production, it is predictably scooped into male-genius territory — resulting in uncreative offspring. Enter Born Sexy Yesterday. In the case of AI, it seems the male genius has a rather limited reproductive imagination bounded by a limited set of fears. After all, is the fear of autonomous machines any different than the fear of autonomous women?

Leeson’s feature movie Teknolust (2003) presents a gleeful vision of creative reproduction unbounded by such fears, with the main character fractured into four identities, all played by Tilda Swinton. The first, Rosetta Stone, is a virginal, nerdy bioengineer genius who has created three artificial intelligences modeled in her image: Ruby, Olive and Marinne. She’s kept their existence secret, insisting to her male colleagues that her theories for creating such “self-replicating automatons” are all still hypothetical. She wouldn’t want to frighten the boys.

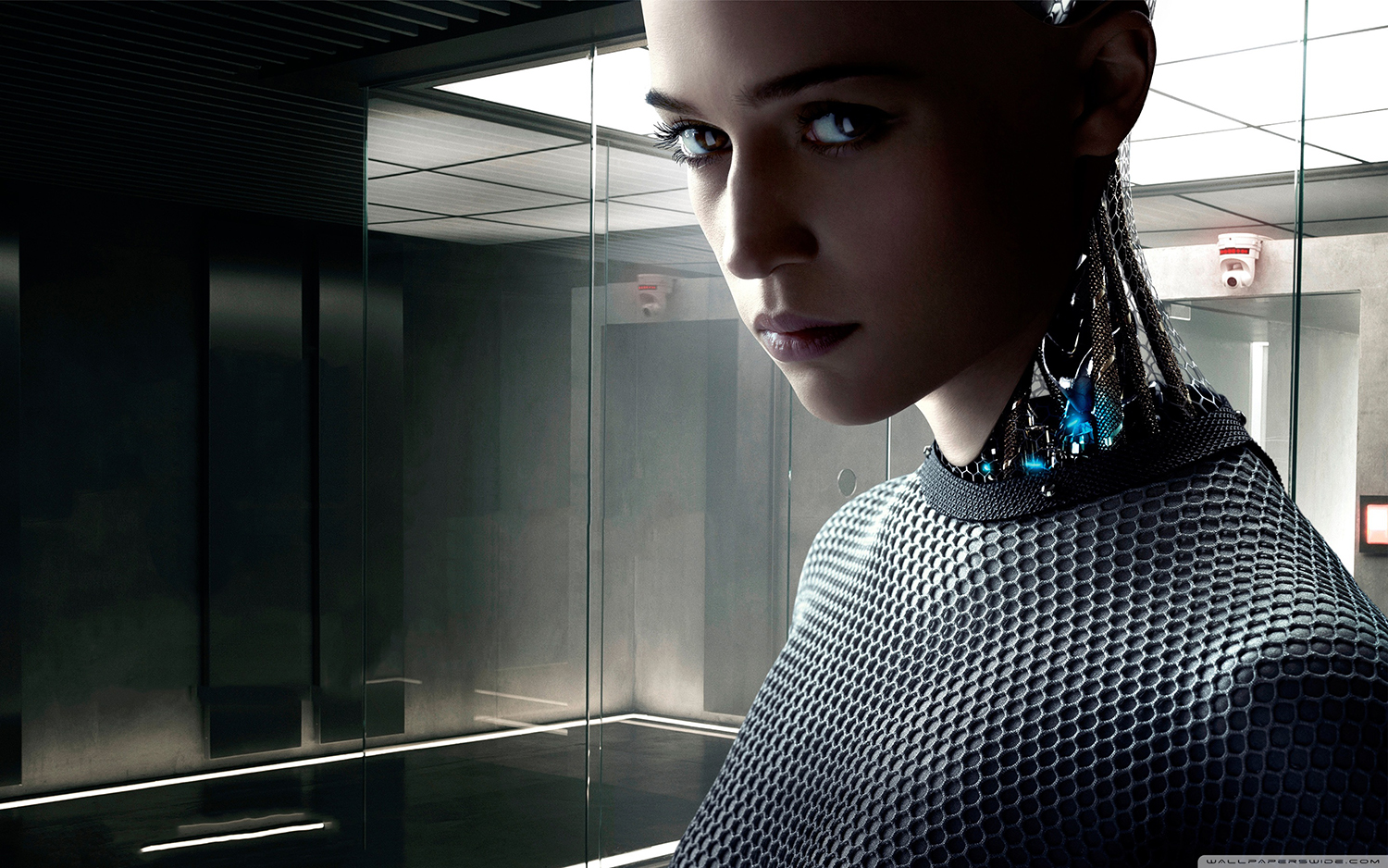

The AI sisters, wearing monochromatic outfits corresponding to their RGB names, seem to be trapped inside the computer system, with the exception of Ruby, who must make regular missions into the physical world to gather sustenance. To survive, all three require regular injections of spermatic fluid. Ruby harvests this from men she effortlessly seduces using lines from classic romance movies culled from the internet. She also turns a profit, ostensibly to keep the servers running, through her nightly camgirl appearances on “Ruby’s E-Dream Portal,” where she recites melancholy lines of verse. Her mystical, seductive presence has made the portal the most popular site on the internet. So popular is she that Rosetta cautions her to “act a little more robotic — no one’s supposed to know you’re real!”

But her realness becomes evident when Ruby’s sexual partners begin to exhibit symptoms of a virus-like infection: impotence and an inflamed forehead imprinted with barcode numbers. The former is most upsetting to the men: “I don’t care about the numbers!” one shouts in quarantine.

Rife with jokes on femaleness and identity signifiers, Teknolust is a story of sexual liberation rather than sexual dependence. Instead of being Born Sexy with no socially learned sexual prowess, beguiling men is precisely what Ruby excels at. Her personal breakthrough comes via a love relationship with a man in which she teaches him in the bedroom, discovering an intimacy whereby sex is but one component.

Leeson had previously cast Swinton in Conceiving Ada (1997), in which a woman computer scientist obsessed with pioneer Ada Lovelace time travels to the nineteenth century to communicate with her through an invented AI “agent.” Lovelace’s story is tragic: without the legal right to control her own reproduction, she suffered through painful pregnancies and died young of uterine cancer. She was deprived of the freedom to exercise her computational brilliance, for which she was regarded alternately as harmless dilettante or heretic. “I’m not at all certain that half a life is better than none at all,” says Leeson’s Ada—a statement equally applicable to a disempowered AI in female form. But in Conceiving Ada, the protagonist discovers a way to give Lovelace a second, full life. Downloading Ada’s consciousness into her own DNA, she gestates a daughter: Ada’s reincarnation with the brilliant mind of a computer scientist in a child’s body. In other words, a perfect inversion of Born Sexy Yesterday.

Conceiving Ada is a clear precursor to Teknolust not only for its focus on the embodied realities of female scientists, but for the way it reimagines reproduction as invention: reproduction of self through artificial means; reproduction of identity through artificial intelligence; reproduction of ideas — not only genes — through future generations.

Teknolust’s Ruby led a further life in the form of a chatbot on Agent Ruby’s E-Dream Portal (2002), a website where she engaged in continuous chat, learning, remembering and emoting. Later, Leeson built a bot called DiNa with even more sophisticated conversational skills. “Men seem to like Ruby more,” said Leeson in a 2005 interview. “She’s funnier and quirkier, and they are put off by DiNA’s intelligence.”[1]

Identity is an artificial intelligence: that idea is nothing new, and nothing endemic to advanced technology. We are all multiple, invented selves, and the freedom to invent them and reproduce them is fundamental to our agency. Ruby gains her “freedom by way of polyphony,” to quote Peter Weibel.[2] That polyphony is what the Born Sexy Yesterday character lacks, and what Leeson and her selves achieve. It’s only a matter of time until Ruby reincarnates again, smarter and stronger. The future is pregnant with possibility.