A profile of Lutz Bacher requires reimagining what a profile is, which is just fine because her art asks similar constitutive questions of itself. You have to let go, and of what can be hard to pin down, but you can tell that you have to, and at the risk of sounding saccharine, it is something to do with love or something like love, whatever that is.

Once you begin, the catalogue is endless. You can’t stop. The catalogue of love, I mean, and what we might also call longing, desire, a kind of sweetness. It’s funny, perhaps, to speak this way about the notoriously reticent American artist known for her spare, anarchic, conceptual work and pseudonymous identity. But Bacher is funny. And I never thought Lutz sounded like a German man’s name anyway. More like an old-fashioned dance step, something lilting and loping and unpredictable — a waltz-shuffle-moonwalk-pirouette.

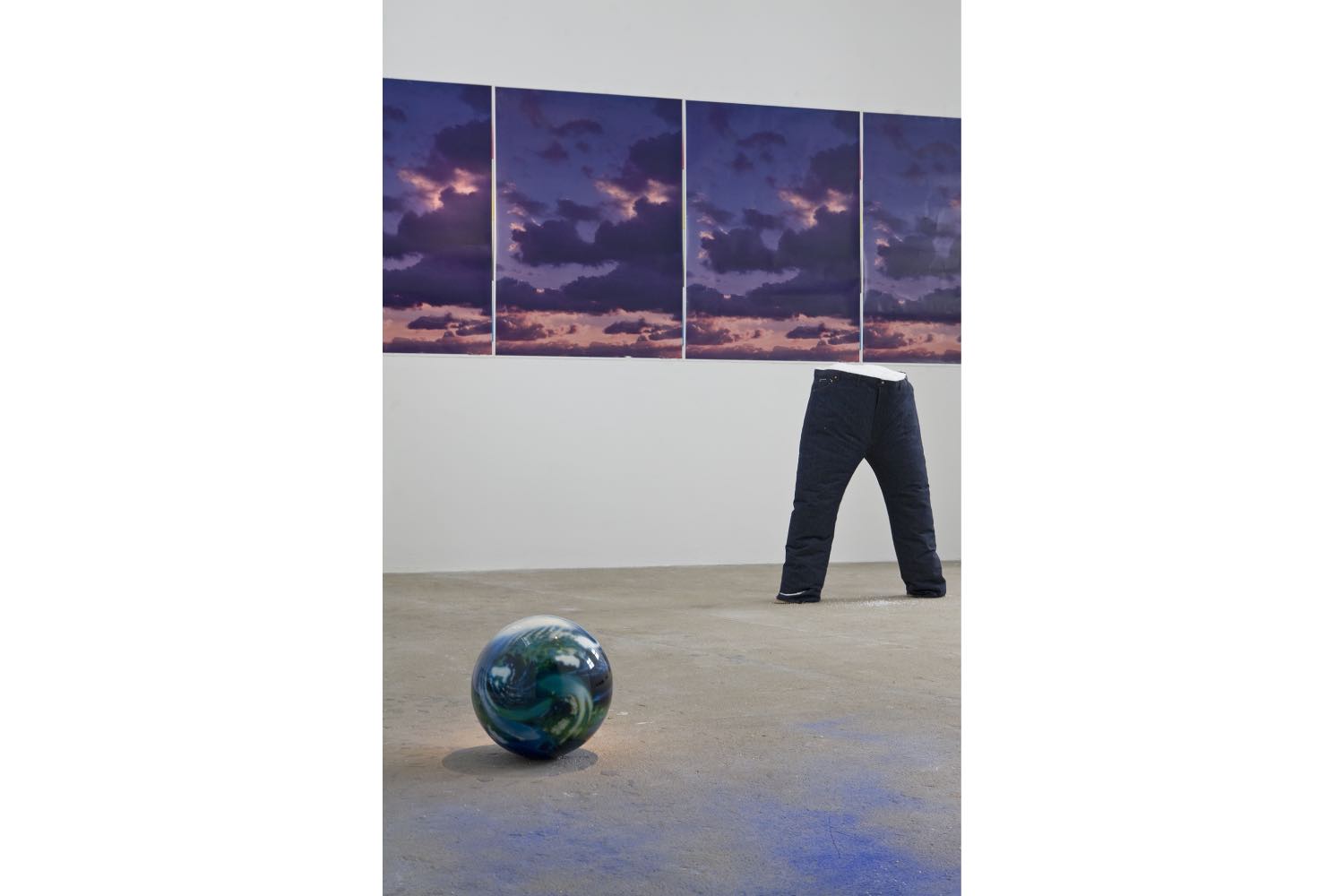

Maybe the catalogue of love begins with In Memory of My Feelings (1990), a series of T-shirts printed with personality test statements (“My mother was” — you fill in the blank!) and housed in a filing cabinet, and ends with Sunsets (2004), four large prints of the same setting scene, blush pink sky and cotton floss clouds. Or maybe it begins with Orb (2008), “a large white orb made for an unknown purpose,” with its grubby and pocked Styrofoam ridges, and ends with Edward (2011), a sfumato lithograph rendering of the smoldering vampiric love interest of the Twilight series. Or maybe it begins with Oz (2008), another lithographic filmic homage via a standing cutout of the famously lacking trio on their way to the Emerald City, the Tin Man pointing the way to where he might finally get the heart he has been missing his whole life, and ends with Tin Man (2012), a painted rubber Halloween face mask of the hollow-chested protagonist. Or maybe it begins with Heart (2010), a large painting of a ruby-red anatomical heart spraying blood from its lower left quadrant, and ends with Angels (2013), a huge broken mirror that reflects, in splinters, slivers, fragments, fractals, crystalline views, whatever scene surrounds it.

Either way, it goes on and on and on — a kind of roaming desire, a kind of bleeding, spreading, pooling. We might think of suffusion as the logic of Bacher’s exhibitions, in which some of the above works appear configured and reconfigured, but, most of all, the spaces are often filled with something immaterial and boundless — sound. The haphazard honky-tonk of an electric organ on the fritz seeps through the door to the next room. Somewhere upstairs, Leonard Cohen sings a glitchy, pleading refrain from “I’m Your Man,” looped and degraded so that “please” is almost a growl, as we know it can be. Background pianos tinkle and string arrangements swell in manipulated film clips on the edge of sentimentality. In What Are You Thinking (2011), a dialogue from the 1988 film adaptation of Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984) loops over a juddering white screen. “What are you thinking?” Juliette Binoche’s character, Tereza, asks her lover Tomas, played by Daniel Day-Lewis. “I’m thinking how happy I am,” he replies, as they drive along a country road just before dying offscreen in a car crash. Am Happy (2012) shows four seconds from Legends of the Fall (1994), the epic American Western blockbuster so beloved by women of my generation that I gasped with recognition. “A-M H-A-P-P-Y” writes the infirm patriarch of the tragic Ludlow family on the chalkboard hanging around his neck, having lost his powers of speech to a stroke. The letters are shaky and jagged, the music surges, and Bacher’s video cuts to black just as Ludlow Sr. reaches the bottom of Y.

In other exhibitions, a song travels through cavernous spaces so that you might try to follow it like a beacon to its disembodied origin, all the while surrounded, wandering through its presence like a magnetic field. Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata.” Nina Simone’s cover of Fairport Convention’s “Who Knows Where the Time Goes?” Claude Debussy’s “Clair de Lune” features in a clip from Twilight, in which the aforementioned undead hero earnestly butchers the French composer’s name: “Deboossy,” he says, he is moved by Deboossy and hopes his human paramour will be too. Perhaps he has stayed up nights for the last century reading and listening to Deboossy, thinking about his undead plight. I know I would.

In Bacher’s installations, music and sound are like lonely strains of thought, red threads and heartstrings gone awry. They pull you toward them and catch you off-piste by refusing closure — looping, crackling, fading, cutting off short. Bacher’s work unravels the materiality of technologies that record and reproduce, eroding and upending them, but not as straightforward critique. Her manipulations are slight, humorous, and hopeful — deceptively simple offerings that cut marrow-deep if you let them. It just takes time.

Of KMS (2016), her short-range radio symphony of overlapping opening sequences of Roberta Flack’s 1973 hit “Killing Me Softly,” Bacher said, “The oohs and aahs are all we have, that is our primary language: desire, just oohs and aaaahssss.” In the piece, a trio of Sony transistors tuned to the same pirate radio frequency play the song’s epic, crooning preverbal bridge, each at a slight delay from the next in a desirous, cycling reverb, cutting off just before the vocals arrive. Flack’s muscular, soaring vowels summon a body turning and turning, waiting and waiting and waiting to tell how he killed her softly with that good song, singing her own slaying song in return, and all this inside Bacher’s analog lullaby.

Crimson and Clover (Over & Over), Bacher’s 2004 elegy to her dealer Colin de Land, treats longing duration in a similar fashion, at once raw and irreverent. The single-channel video captures, at akimbo angles and fragmented, up-close views, the avant-garde metal band Angelblood (Lizzi Bougatsos, Rita Ackermann, and David Nuss) for thirty minutes as they soundcheck and then play at de Land’s memorial service at CBGB, the notorious East Village music venue. Angelblood’s version of Tommy James and the Shondells’ 1968 hit, probably one of the most beautiful love songs ever (see, too, the 1981 cover by Joan Jett and the Blackhearts) is drawn out and out, rippling with feedback and wild, guttural vocals. As per the lyrics and the title of the artwork, they sing “over and over” over and over and then over and over again as Bacher’s video ends and begins once more. “My my, such a sweet thing (da-da-da-da-da-da-)”.

In Bacher’s work, absence is as significant as presence. She knows what notes not to play. Exhibition and artwork titles pull on the imaginary of popular songs that ring through the mind without being heard: “What’s Love Got To Do With It” (Tina Turner), “In My Secret Life” (Leonard Cohen), “Do You Love Me?” (the Contours), and “More Than This” (Roxy Music). I’m sure there are others.

An exhibition titled after the Contours song, about a man who has learned to dance in an effort to impress his admired, includes Big Boy (1992), a giant stuffed white male anatomical doll lying on his back on a sculpture called Villa Savoye (2009). Big Boy stares up at the ceiling, his tiny pink anus puckered like a rosebud, his matching-hued tongue lolling like a maniac, as Sea of Love (2009) plays behind him. I haven’t seen Sea of Love in person, but Bacher’s description of it in her 2013 monograph, Snow, has it running through my mind for days like a rhizomatic, romance-obsessed Ohrwurm: “Multiple projections depicting objects & events appear & disappear suggesting alternate evolutionary paths through twisted Oedipal scenarios or incessant wanderings among orbiting space debris – to the tune of – Sea of Love – God Only Knows – Love Hurts – THINK – What You Do To Me – STOP – In The Name Of Love –”

Is Big Boy dreaming of the sea of love, somewhere near Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye, whose closest body of water is the unglamorous English Channel? Did Big Boy dream the exhibition itself, fill it with thoughts of aspiring admiration now that he can finally do the mashed potato and the twist? Does he want to know now if we like it like this?

In the exhibition named after Roxy Music’s anthem for the unrequited, large ink-and-paint canvases of leafless black tree boughs are tacked around the gallery walls, the floor scattered with sections of giant plastic white tubing like ancient bones or relics, portals to a subterranean universe. The lighting is set to dim hourly, and a slowed-down track of birdsong field recordings plays on a loop. On the wall, mounted and framed, is a picture of Bacher’s Ape (2009) — a giant stuffed ape — sitting in a tree, and two pieces of paper on which are handwritten the lyrics of “More Than This.” “Tell me one thing / More than this,” they implore, and I can’t.

An artist profile might chart the “evolution” of an artist’s work and how it changes or “matures” over time, but to me, Bacher’s oeuvre is entire. Every work is different but entirely Lutz, as in unpredictable, spare, hilarious, and profoundly moving in its artless generosity. Her materials are unpreciousness incarnate so carefully orchestrated, with so much space for any viewer, that they attain the preciousness of briefly inhabiting another’s consciousness. We see what moved or attracted Bacher on any given day, what she made of it, and how the work works on the assumption that if this attention is shared or translated, it might move us too. It’s easy to forget how much you can love things.

In one of her rare public talks, featuring even rarer intimations of her personal life, Bacher pulled down her trousers before sitting in a leather chair as her sometimes-collaborator Peter Currie drew on a chalkboard behind her. She was wearing another pair of trousers beneath but no socks. Reading from a sheaf of papers, the artist recounted childhood anecdotes — the movies her family watched, parental advice — frequently bursting into full-throated laughter as if she couldn’t help herself. She had a teacher named Mrs. Love. Mrs. Love, Bacher says with emphasis and laughs. She recounts her math classes: “I could do equations, but I just didn’t understand: What is X? What is X? What is X?” She laughs again and then again, describing a book report she hadn’t prepared about a Groucho Marx biography. “This book is so funny,” she kept saying to the class, “then I couldn’t stop laughing.” She laughs again, over and over.

In the twelve-hour video work Do You Love Me? (1994), Bacher remains behind the camera as she talks to friends, family, and colleagues who are captured in partial view. With one, Bacher speaks of art in which there is no figure. “The difficulty of imagining… what happens if there isn’t… a figure…” a man says. “Mhmmmm,” Bacher intones, as she often does, volunteering no answer. Watching this, I thought of the artist’s work in which an empty room was slowly filled with smoke. In video footage of the installation, Bacher and her assistants laugh as the machines puff away and their forms grow distant and blurry to each other. “This is great,” one says, suddenly emerging from the haze. “Come over here, to this side, you can’t see anything.”

In Bacher’s work, you are the figure. You are like Frank O’Hara in his poem “In Memory of My Feelings,” you have “several likenesses, like stars and years, like numerals.” You are asking “do you love me” and waiting and waiting for an answer, and there is nothing, nothing, more than this.