In 1977, Flash Art featured a survey of “non-aligned” Russian artists. Throughout the 1980s, the magazine continued to report on the phenomenon of Soviet Nonconformist art, mainly through the criticism of Russian expat Victor and Margarita Tupitsyn. Gathered in conversation, Boris Klyushnikov, Alexandra Novozhenova and Andrey Shental reinterpret the emergence of those experiences not in spite of but thanks to the identity of the Soviet political system.

In 1977, Flash Art featured a survey of “non-aligned” Russian artists. Throughout the 1980s, the magazine continued to report on the phenomenon of Soviet Nonconformist art, mainly through the criticism of Russian expat Victor and Margarita Tupitsyn. Gathered in conversation, Boris Klyushnikov, Alexandra Novozhenova and Andrey Shental reinterpret the emergence of those experiences not in spite of but thanks to the identity of the Soviet political system.

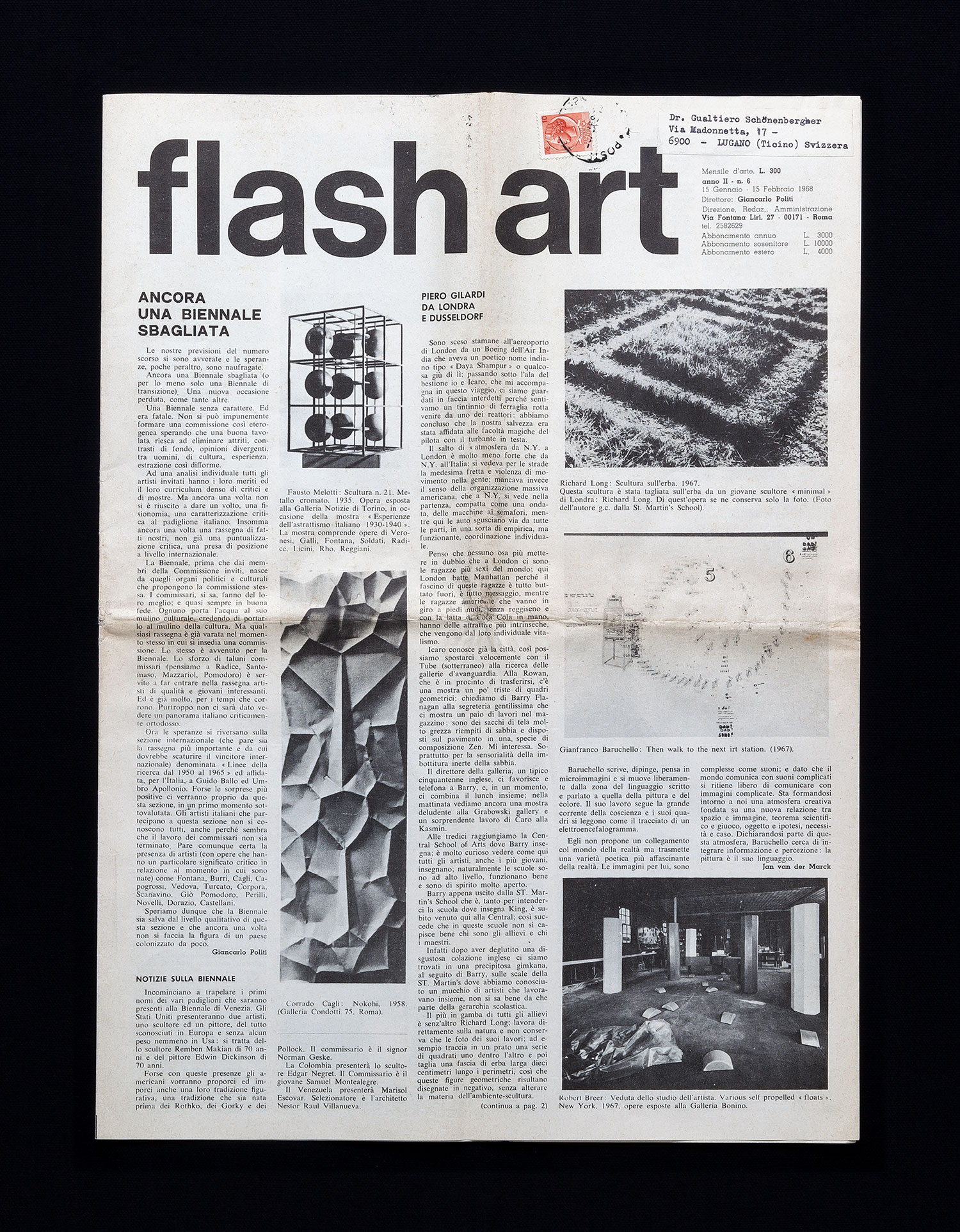

Andrey Shental: After the legendary “Bulldozer” exhibition, held on September 15, 1974, in the urban forest near the Belyaevo Metro Station in Moscow, Soviet “unofficial artists” began to appear in foreign media. Yuri Leiderman, a member of the artists’ collective Inspection Medical Hermeneutics, described Flash Art as “a miracle union with ‘big culture’ and ‘the West.’”[i] But how have relationships between artists and magazines changed in the “post-critical” age?

Alexandra Novozhenova: There is a popular myth about the Soviet artist of the 1960s and ’70s, whose world was turned upside-down after seeing Pop art reproductions in a foreign magazine for the first time. But that would have required a very powerful withholding of information. Today, centralized art-related mass media outlets have become worthless in this regard. It is curious that conceptual artists of the 1970s, like those included in Flash Art’s 1977 survey on Soviet “avant-garde” art,[ii] are presented as completely independent and unknown actors. Actually, conceptualists had their own inner exchange networks (let’s say, mail art) connecting Eastern Europeans both between each other and with their American peers. Despite the “iron curtain,” their internal communication was up and running. However, this compilation gives the impression that artworks were smuggled into the magazine illegally. Such an uprooting of conceptual practices from media platforms and the networks that sustained them reveals an intention to institutionalize these artistic expressions.

Boris Klyushnikov: The year 1989, when the Russian version of Flash Art was launched, was the last moment in history when the symbolic division between the East and the West existed. A publication in a professional magazine — and not in an artist-run journal like A-YA — symbolically legitimized an artist. So this was the last moment when one could document a reaction like Leiderman’s. After Perestroika this role of media was reconsidered. For instance, representatives of Moscow Actionism already had differing views from the theoretical stance and editorial activity of an art magazine like Flash Art.

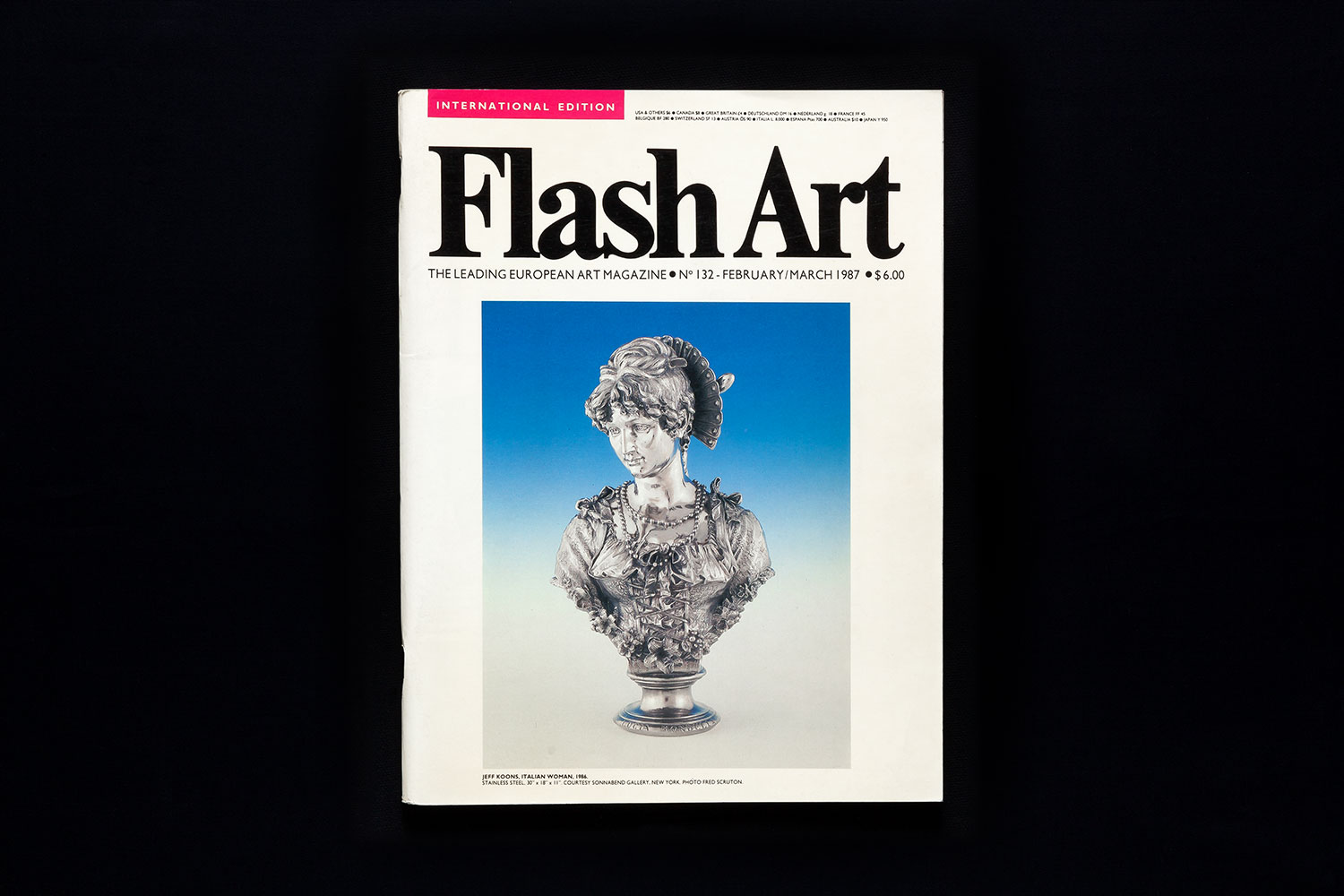

AN: Margarita Tupitsyn’s essay “From Sots Art to Sovart”[iii] reads like a manifesto for integration — so the magazine here is used as a tribune of sorts to articulate this position, which Tupitsyn shares with her fellow artists. Ilya Kabakov and Erik Bulatov in their interview,[iv] published in the same issue, use the pronoun “we,” acting as representatives for the whole Soviet artistic community. They discuss the inferiority of the Soviet subject, who is traumatized by utopias, and feel obliged to overcome it. Today, one could see that integration with the West was understood in terms of overcoming an inferiority complex.

AS: And the medium of that integration was post-structuralist discourse. After emigrating to America or Western Europe, critics started importing Soviet art in exchange for exports of new language. It seems that Victor and Margarita Tupitsyn tried to cover up the difference with the pompousness of their style, which today sounds rather archaic, instead of exposing and explaining it.

AN: It is funny that the absorption of Barthesian-Deleuzian slang is intertwined with a historical analysis of a situation that is absolutely transparent in terms of its ideological implications, namely the successful inclusion of Soviet artists into an international context. I find it crazy to speak of Komar and Melamid’s art in terms of Anti-Oedipus or schizoanalysis. But for the Tupitsyns, Soviet words consist solely of ideology. It was a pure product of superstructure, which is reducible to the set of symbols that one should shuffle and subvert. Suddenly, in her account, this empire of signs is interrupted by real events — the “Bulldozer” exhibition, for example. But even such a supposed political defeat of the state is presented in their texts as an artistic triumph of the empire of signs.

BK: The “Bulldozer” exhibition marks a split in the ways Boris Groys and the Tupitsyns connect art and theory. Groys privileges totality, developing Kabakov’s idea of the total installation, and is also close to the Collective Actions Group in his embrace of the romantic. The Tupitsyns share the arbitrariness of signs that is at stake in the art of Komar and Melamid, who took part in the “Bulldozer” show. I mean, we can see parallels between the artistic methods of Bulldozer artists and the theoretical views of the Tupitsyns. Arguably, they hollowed out signification because the show was oriented toward representation by foreign journalists. As for Kabakov and Andrei Monastyrsky, who did not take part in it, later in their own performances they reflected surveillance technologies and community organizing.

AS: As was quite rightly noted by Alexandra, Flash Art authors overestimated ideology. In the 2000s, Ekaterina Degot suggested another category for Soviet Nonconformist art: “communist conceptualism,” thus inaugurating a completely different approach.[v] Distancing herself from the cultural context, Degot took into account the specificity of the Soviet economy. What other methodologies might you find relevant for a contemporary reading of those experiences?

BK: What I find interesting is the revision of the notion of the “romantic.” Groys begins his famous 1979 essay “Moscow Romantic Conceptualism”[vi] by claiming that this term is inappropriate to various artistic practices that he goes on to describe. But, in my view, his understanding of the romantic corresponded very well with the character of those works. When we analyze art theory today, we see it in dialectical relation to conceptualism. For instance, in his book Anywhere or Not at All (London: Verso, 2013), Peter Osborne states that romanticism was the first conceptual art, because it claimed primacy to language, to linguistic ontology. Philosophy in art begins with the Jena Romantics and their confrontation with the Kantian project of judgment and the history of taste. At the same time, Art & Language or Joseph Kosuth could be described as romantic. This concept, long neglected by Groys himself, is a fitting description. For instance, Jörg Heiser in his exhibition “Romantic Conceptualism” (Kunsthalle Nürnberg and BAWAG Foundation, Vienna, 2007) tried to reinscribe romanticism into the general narrative of Western conceptual art.

AN: I find it productive to consider conceptualism not as something opposed to Soviet reality, but as its dialectical outcome. The text that introduces the 1977 Flash Art survey says that none of those artists opposed the system, but nevertheless they existed within “semiofficial” or “nonofficial” territory. Notably, the first case in this selection is a member of the Dvizhenie group, Francisco Infante-Arana, who was successfully integrated into the Soviet exhibition system. For instance, research institutes and world expositions provided the group with platforms for official exposure. In the same introduction, it is also stated that artists’ means of subsistence had nothing to do with their real interests. However, post-Soviet experience has shown us that the same alienation is at work in the capitalist art system. So I am interested in keeping track of how artists lived within a condition of “really existing socialism.” How did platforms such as the “philosophical laboratory” of Collective Actions emerge? How come these phenomenological experiments took place? Is it related somehow to the Era of Stagnation during the rule of Brezhnev? This art originated not in spite of but thanks to the Soviet system. It seems many writers of my generation share this perspective.

BK: The laboratory-like withdrawal from the everyday was possible thanks to an imaginary West that was envisioned as an escape from Soviet life. Being situated within global capitalism, today we see that the differences between East and West were fictional.

AS: Curiously, there is a version in which the “Bulldozer” exhibition was itself fictional and was staged for Western journalists. Today we could read it as the first media performance; so a genealogy of 2010s Actionism (Pussy Riot, Petr Pavlensky, Katrin Nenasheva, etc.) might come from there and not from the ’90s. The classic Moscow Actionism of Oleg Kulik and Anatoly Osmolovsky was designed for local press and TV, while contemporary street performance is oriented toward international media to somehow tease the “sovereignty” of Russian power.

AN: It would be enough to see what Western universities or media demand from Russian art. They are captivated by such bright episodes as the political persecution of the intelligentsia, comparing Kirill Serebrennikov, the theater director arrested last August over accusations of embezzling government funds, with Vsevolod Meyerhold, who was arrested, tortured and executed during the Great Purge of 1940. The cases of Pavlensky or Pussy Riot define the main agenda. Recently, I was asked to give a lecture within the framework of the celebration of the centenary of the Russian revolution, and the title was already set: “Art Under Putin.” The rest of artistic production does not fit into this category; this is an enormous reduction of meaning when it comes to the Russian and post-Soviet situation. Especially starting from the so-called “Cold War II,” the Western perspective on Russian art has become polarized: the “good” Actionists and the “monstrous” authority figures. In big media there is no room for a more nuanced analysis or leftist critique of the post-Socialist condition. And media can promote such an agenda due to the powerful viral effects of these actions.

AS: What bothers me is that these artists reproduce opposition typical of late-Soviet liberal intelligentsia, like that described in Flash Art: the lonely warrior who opposes the authoritarian regime. In fact, it is well known from political science that Putin’s regime is categorized as hybrid. It only tries to look more authoritarian than it can be; and thanks to these artists the system can start to bear its teeth — and this how journalists would like to depict it.

BK: Today, in the internet era, we can no longer speak of internal and foreign agendas. These various images and texts are reformatted from the point of view of larger narratives, bigger histories. For instance, reposting and sharing images of Pavlensky in front of the burning doors of the Lubyanka [on the night of Monday, November 9, 2015, Pavlensky torched the entrance to the headquarters of the FSB security service, the successor to the KGB], internal network communities reacted to it differently. These images exist in micro-situations, and only later is commentary attached to them in the service of this or that political purpose.

AS: Speaking of the “art of Putinism,” I recall Arseny Zhilyaev’s fictional museum: “M.I.R.: New Paths to the Objects,” at the Kadist Foundation, in Paris, in 2014. It depicted the world to come as Putin’s Gesamtkunstwerk. On the wall one was able to see a chronology of avant-garde art: from Collective Actions to Pussy Riot. In this work Zhilyaev flirts with the global art world’s expectations: “I am a Russian artist in residence at a Parisian institution and I make art about Putin,” he seems to say. One could read his gesture as a potential “sublation” of those oppositions, wherein Putin himself becomes an artist, like Stalin in Groys’s account.

AN: Of course. But what interests me in Zhilyaev’s art is that he produces all-inclusive frame-like structures. He is a dominating artist who subjugates the most significant manifestations of mass media discourse on political art, appropriates entire timelines and art histories and adds his own signature. One could criticize this strategy, but strangely enough the impudence and megalomania in his claims to the totalitarian appropriation of discourse is actually what constitutes the very artistic strength of his practice. It is hard to imagine how one could appropriate this media discourse, but he finds a way to do so. So in a sense his practice reverses the reductive damage done to Russian art by mass media: Zhilyaev extracts activism, already simplified by the media, from its mediatic context and locates it within a larger historical framework that itself becomes the actual object of his art: his art object is an appropriated media metanarrative.

BK: He does not merely criticize Russia’s position in the international context, but rather comments on the ways art is described. The rhetoric of contemporary art historicization and its terms (performativity, new media, etc.) — all of them could be subsumed into different situations. One should rather read it as critique of art as an institution, in which Putin can become a contemporary artist. In the ’90s, it looked like the project of contemporary art was critical a priori. But Zhilyaev shows that the art vocabulary, at least in the museum context, is subject to a political agenda — a futuristic Putinist Russia, in this case.

AS: Boris, you organized a show, “Freedom is Freedom” (Belyaevo Gallery, Moscow, 2014), on the occasion of the fortieth anniversary of the “Bulldozer” exhibition, in which members of the U/N Multitude group were literally licking an actual tractor to debunk the cult status of this event. You also interrogated artists in that context, and some of them said that the “Bulldozer” exhibition “had no historical importance.” However, today there is a tendency to organize anti-institutional exhibitions in private apartments, similar to what Apt artists did in the 1980s. Is there anything in the phenomena featured in Flash Art — conceptualism, Sots art, Apt art — that is relevant for younger generations?

BK: In fact there is a significant transition from the climate that the interviews we conducted in 2014 registered. Since then, we have witnessed a growing interest in conceptualism and its models for survival within artistic communities (I think, for example, of Yan Tamkovich’s research on forgotten conceptualist Joseph Ginzburg and Kabakov’s graphics or Kirill Savchenkov’s installation Office of Sensitive Activities / Applications Group, 2017).

AN: I have the impression that in the beginning of the 2010s young artists, especially those associated with the Rodchenko Art School, thought only about conceptualism. For instance, Petr Zhukov or Dimitri Venkov investigated the phenomenology of appearance and presence in vacant, out-of-town spaces; or Anastasia Ryabova, who is interested in revealing how schizophrenic conceptualist art bureaucratization could be, makes works that pursue a cross-fertilization between artists of different generations, such as Monastyrsky. Notably, the above examples are closer to Collective Actions, because it is all about how relationships are formed and documented. Kabakov and Sots art is a different story; it is a dead end.

BK: Conceptualists made their way into Flash Art criticism thanks to their gestures, while contemporary artists are more interested in their embeddedness in everyday Soviet life. From their point of view, Kabakov is important as a representative of children’s book illustration. Today one could read it more contextually as a work within culture, and not as a succession of artworks or the development of specific artistic strategies.

AN: According to Kabakov, the children’s illustration from which he earned his living was probably mechanical hackwork; but for us it could be the only entry point, because it is not in opposition to Soviet artistic reality. It is, rather, an index of this reality and represents its dialectical plane. Conceptualism is interesting as a partial contribution to the Soviet project and not as something that longs for integration with the West, breaking free from socialism and getting rid of the inferior socialist subject.