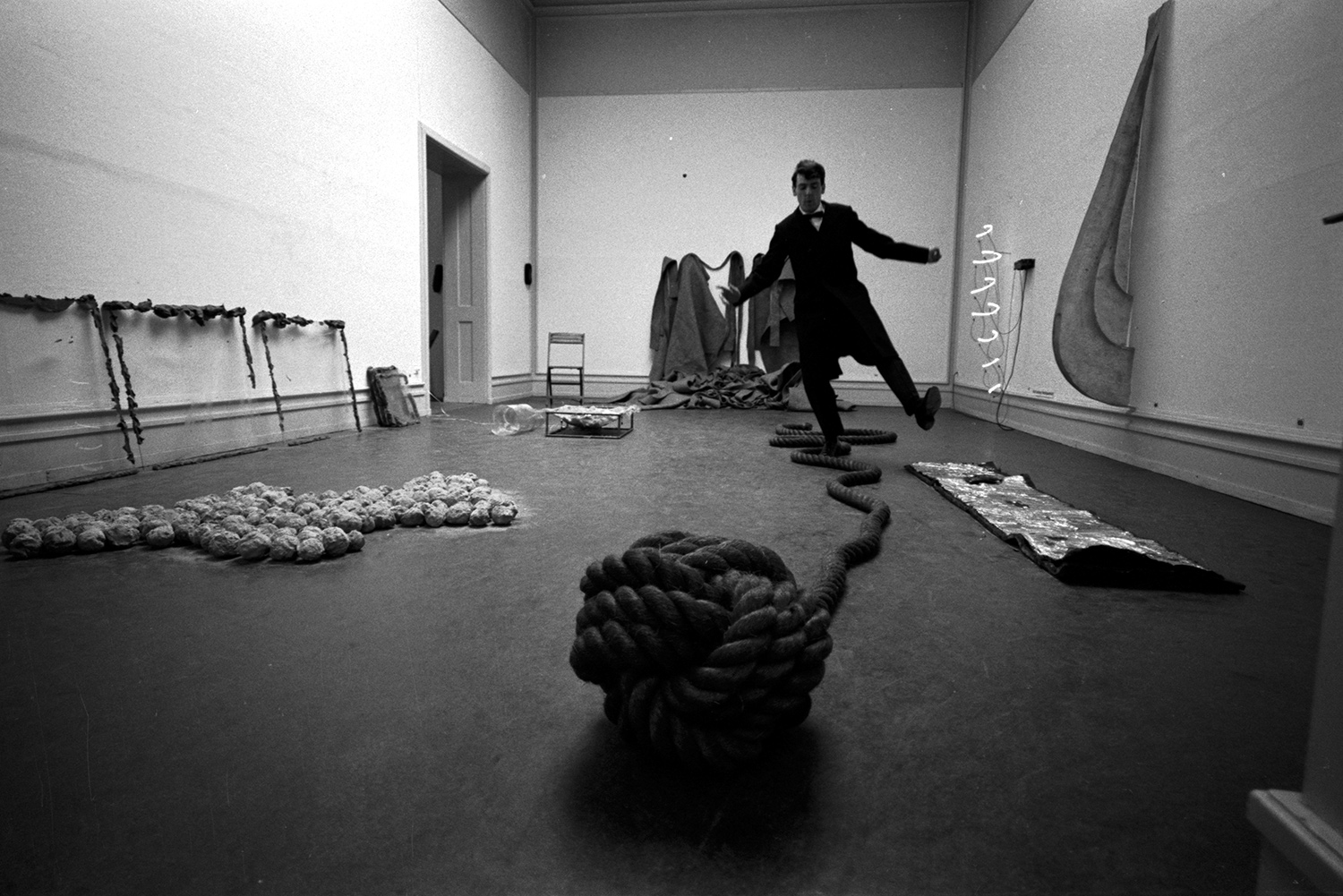

Sound as art emerged in the counterculture 1960s as a lively, open-ended alternative away from the center. Practitioners with backgrounds in disparate fields — such as music, performance, literature, visual art, and the moving image — took to experimenting with a range of sonic configurations. Feeling unconstrained, they explored consumer audio tools alone in their studios, or in the supportive environment of developing artist-run, nonprofit spaces where intermedia investigation was the norm. During this early phase, contemporary art museums were concentrating on concrete, commodifiable forms, namely painting and sculpture. These institutions considered sound an anathema, and were horrified by how it appeared as fluid as water and wantonly would invade sacrosanct white-cube spaces.

By the late 1990s, museums had started to contemplate sound as an exhibitable art form, bolstered once they hired skilled audiovisual technicians who understood how best to install sound artwork. This involved meticulously arranging specific equipment to present work according to an artist’s aesthetic intention, and making careful use of sound baffling materials that stopped sound from escaping all over the place.

What exactly is sound art? And who considers themselves a sound artist? Is sound art simply a catchall term for multifarious art made using the latest consumer electronic tools and audio systems? While definitions and theories are at best temporarily relevant and all-but-impossible to nail down, artists continue to thrive, inspired by sound’s open-endedness. Rather than be pigeonholed by labels, most practitioners favor the simplest term, artist. This suits their approach to creating a sound-based artwork that might materialize as an installation, a performance, an immersive virtual reality environment, or even an online audio file. More than ever, the field’s diversity means that sound art belongs to the here and now as it steadily evolves with technology, with the times, and with its users.

The future of sound art appears bright, especially in outdoor spaces. Post COVID-19, parks and sculpture gardens inevitably will be commissioning site-specific sound art installations, encouraging properly masked audiences to listen closely and even linger with the work as they practice social distancing. COVID has similarly motivated online opportunities. During the lockdown, artists remained active, using social media for the self-distribution of streamable and interactive new sound works, in the same way that during the topsy-turvy late 1960s and early 1970s innovative recordings reached interested audiences through offbeat radio stations and mail-order distribution systems. In due time, artists will be unveiling new forms of expression. We will need to pay attention, because fresh ideas always appear out of the blue, without fanfare.

Over the last few months, artists have been resourceful in using sound and media technology to forge alternatives, presenting solo performances live from their studios or in what were shuttered galleries. Meanwhile museums fell back on their own archives and began streaming documentaries of past avant-garde performances that took place in their spaces. Many also launched online exhibitions of single-channel videos and films from their collections.

History reveals that sound art thrives in the unmapped terrain of interdisciplinary art practice, in tandem with steadily evolving technologies and social systems. Whether in a do-it-yourself or a polished manner, artists engaged with sound belong to the here and now, and today their work is stronger and more relevant than ever. Sound is delightfully mutable: as fluid as a river, as tough as steel, or as delicate as a birdcall.

What follows are recent cases in point, examples of original work by innovators who defy convention with their insightful sound-driven art.

Jana Winderen (b. 1965, lives in Oslo) explores the aural dimensions of landscapes that are difficult to reach, and sounds that are imperceptible to most people. The sounds she records in nature become the components of compositions she develops. The immateriality of sound suits her interests, especially the way sound tends to be perceived intuitively in advance of the rational workings of the mind. Ultrafield (2013), her ambisonic installation with sixteen carefully arranged speakers, aurally transports listeners down into the depths of the ocean, to hear the vocal clicks of whales and the subtle drone of boat motors, before taking them up to the surface of a river where the rhythmic sounds of canoe oars can be heard. The installation then goes skyward into the domain of chirping birds and echolocating bats. After a brief pause, the twenty-minute sonic cycle gently begins again. Listeners have space for imaginative readings of the aural realities unfolding around them, discovering the commonalities of sounds and discerning the transition from underwater to midair.

Winderen describes her compositional methodology as “blind” field recording, meaning she is open to chance. For Ultrafield, she used especially long cords and a range of sensitive microphones, including hydrophones, that she dropped hundreds of feet deep into the icy ocean at the Arctic Circle. After months spent carefully collecting the sounds made by different species of fish, insects, and bats, both audible and inaudible to human ears, she returned to her studio and reworked the material, especially in the ultrasound range above the hearing capacity of humans, as she slowly composed her ethereal work with its harmoniously joined biotic and abiotic elements. Winderen’s sonic universes continue to direct her audience’s attention to what are fragile ecosystems in nature — circuits that encompass all living beings.

The multidisciplinary artist Samson Young (b. 1979, lives in Hong Kong) engages a broad range of disciplines, including music composition, performance, installation, sound, video, drawing, and graphic design. His work is elegant, razor-sharp, and often political in nature, as it addresses the vicissitudes of language as well as cultural and military history.

Muted Situations #2: Muted Lion Dance (2014) revolves around the staging of a traditional “Lion Dance,” with four performers but without the accompanying percussive music. The choreography, the costume, and all other factors pertaining to the performative intent of the dance remain intact as much as possible. As a result, during the recording of the performance, other sounds are revealed, such as the intense breathing of the performers, the verbal communication and cues between the dancers, sounds of the lion’s head rattling, and the stomping of the feet.

This video and sound installation can be understood as a reimagination and reconstruction of the auditory. The sounds of the performers’ own physical exertion — their feet hitting the ground, deep inhales and exhales, the rustling of their clothes — come to the forefront. Young proves that muting is not the same as doing nothing.

Distinguished as visual and film artists, Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard (Iain b. 1973, Jane b. 1972, live in London) always work with sound. It began with their first video, Chain Smoker-Tap Dancer (1995), a two-monitor installation that consists of a pair of unedited, single-take videos of nonstop actions that each performed. The top monitor features a single shot of Iain’s head, presented actual size, as he chain-smokes. The second monitor, placed at foot level, features a single-take shot of Jane’s feet wearing tap shoes and tap dancing. Iain doesn’t speak or make a sound; Jane’s tap dancing is the only soundtrack to the piece.

Requiem for 114 Radios (2016) is a mixed-media, looped-sound installation that includes such disparate elements as filing cabinets, a workbench, electronic apparatuses, and 114 working analogue radios. The installation appears to be an anonymous archive or the abandoned workshop of a radio enthusiast. Scattered across the room on shelves are 114 domestic, analogue radio sets, each tuned to one of fourteen radio frequencies. Each frequency is playing a vocalist singing a dramatic new version of Dies Irae from the Roman Catholic Requiem Mass. Dies Irae was famously interpreted by such composers as Verdi and Mozart, and used to chilling effect by Stanley Kubrick in A Clockwork Orange and The Shining. Requiem for 114 Radios is a testament to the death of analogue technology, as the radios call upon an intricate universe of mysterious messages, modulated hisses, mangled voices, and incomprehensible words. Messages of death permeate a radiophonic babel, and the installation becomes a space for a remarkable and unpredictable performance.

Marina Rosenfeld (b. 1968, lives in New York) is a composer, sound artist, and visual artist. In 1993, she orchestrated an unusual performance art piece called Sheer Frost Orchestra. It was scored for seventeen women, each playing an electric guitar. Sitting in a circle, the women were directed to “play” their guitars in a series of choreographed actions — pluck, scratch, slide, screech — using only nail polish bottles.

Her multipart sound sculpture Music Stands (2019) consists of music stand–like forms and a corresponding set of panels and acoustic add-ons that direct, focus, obstruct, reflect, and project sound. Together the parts play on the relation between aural and social relations signified by the music stand, offering a systematic striation and composition of acoustic and social space that is organized around the materials (aluminum, foam, steel) and modular, relational configurations of the sculptures in space. Each part assumes the presence of hearing/sounding bodies around itself, and is positioned to variously block, amplify, distort, or reflect both visual and aural information according to its shape and composition. Microphones and loudspeakers amplify and reflect ambient room sound, heightening the work’s acoustic presence and subtly amplifying the movements and sounds of visitors and mixing them into the exhibition acoustically. Meanwhile an episodic sound score circulates throughout the work’s sound system as well, momentarily interrupting the atmosphere with brief eruptions of electronic sound and vocality.

Zina Saro-Wiwa (b. 1976 Port Harcourt, Nigeria, lives in Los Angeles) is an interdisciplinary artist whose mediums include video, photography, sculpture, sound, and sometimes food. She has said that as an artist she wants to free herself from super-colonized ideas about her native Nigeria, while expanding what it is to be an activist and environmentalist. Through her art, she wants to expand the meanings of Africanness and, ultimately, to decolonize the idea of the self.

Her installation Table Manners (2016–18) is an eating performance carried out for the camera. In the installation, viewers are invited to sit down and enjoy a meal shown on a monitor. With great gusto and relish, a denizen of the Niger Delta delivers a distinctive eating performance in a colorful setting. The work has a lot to do with place and power. The artist has noted, “A powerful exchange takes place when one not only eats a meal but watches a meal being consumed. One is filled up with an unexplainable and potent metaphysical energy that we normally pay no attention to.”

Saro-Wiwa notes that something is happening in the elemental energy that is transmitted when you’re eating with someone. It’s a powerful thing, and people are discomforted by watching some of these performances. Everything in the food performance is local, everything is a document of the moment at the time that it’s constructed. That leap between reality and performance is what she’s interested in. She recently noted: “You’re watching Table Manners, but you’re supposed to get into some state where actually you access a different truth; but you are not in the way of trying to control. You don’t have that control. You might watch the work, but for me, when you watch my work, the idea is to get to this particular … I always want to use the word fugue state, but then I looked it up, it’s totally not what it is. But I want to reclaim fugue state, because when you are listening to a fugue and when you’re listening to Bach, you do get to a particular place.”

Juan Cortés (b. 1989, lives in Bogota) probes the mysteries of our solar system. He continues the tradition of art and science being entwined in the manner of Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T), which AT&T launched in 1966. The young Colombian maverick draws upon the expertise and energies of Attractor, his close-knit collective of enterprising artists-musicians-designers.

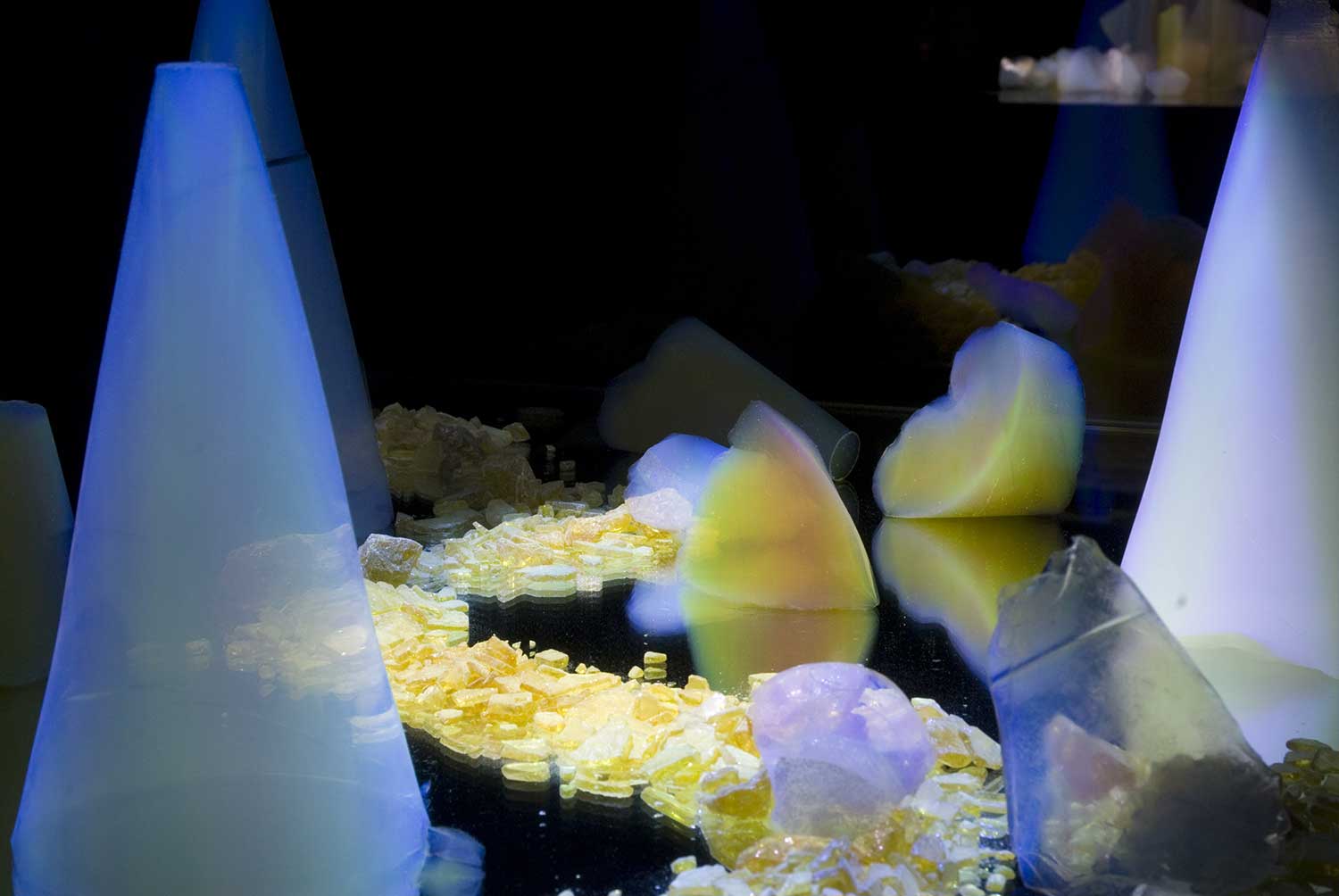

Supralunar is a mechanical representation of how our galaxy’s billions of stars are mysteriously joined together. Cortés’s metaphorical composition appears straightforward, in the shape of a precisely designed metal and Curbell plastic cube that emits light and sound. At the sculpture’s core are thousands of fiber-optic strands that Cortés cut to different lengths and bundled together within the cube. The strands are gently nudged by a clocklike mechanism with long prodding fingers, each of which is driven by a small motor. The strands are illuminated by LED lights installed beneath them. The galaxy is thus portrayed via flickering, star-like lights that are magnified by a lens installed on top of the cube. Through these technological, mechanical, and artistic processes the softly illuminated constellation is projected on the ceiling above. The concurrent composition of discreet sounds is generated by the electromechanical gears within the artwork. Altogether, the sculptural installation forms an enchanting simulation of the morphogenesis of our galaxy.

Cortés likes to think of Supralunar as a gear clock. For him, the clock serves as the perfect metaphor for a complex, intangible phenomenon: dark matter, the hypothesis devised by astronomers that explains how the universe contains more matter than is visible to the naked eye. Cortés recognizes that we usually reference old machines as we develop new models for our ideas about reality. Cortés considers it important to rethink human-machine relations, in order to blur and reconsider the relationships that make up our world.

Bani Haykal (b. 1985, lives in Singapore) is a resolutely independent artist-musician. His humanitarian spirit and can-do attitude have particular relevance today. His current obsession is looking at language as a starting point for imagining the future. This started when he thought about English words that don’t exist in the Malay language.

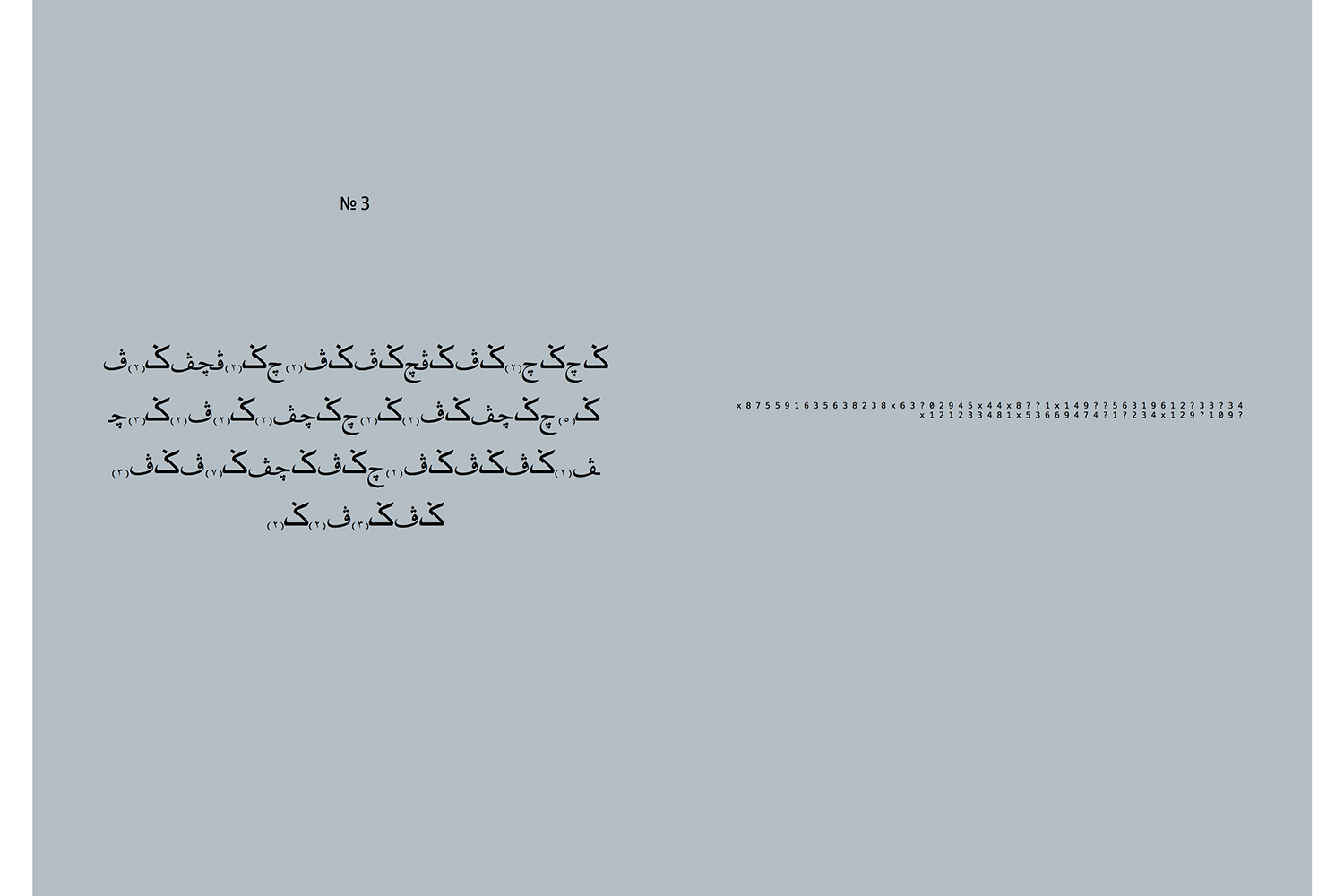

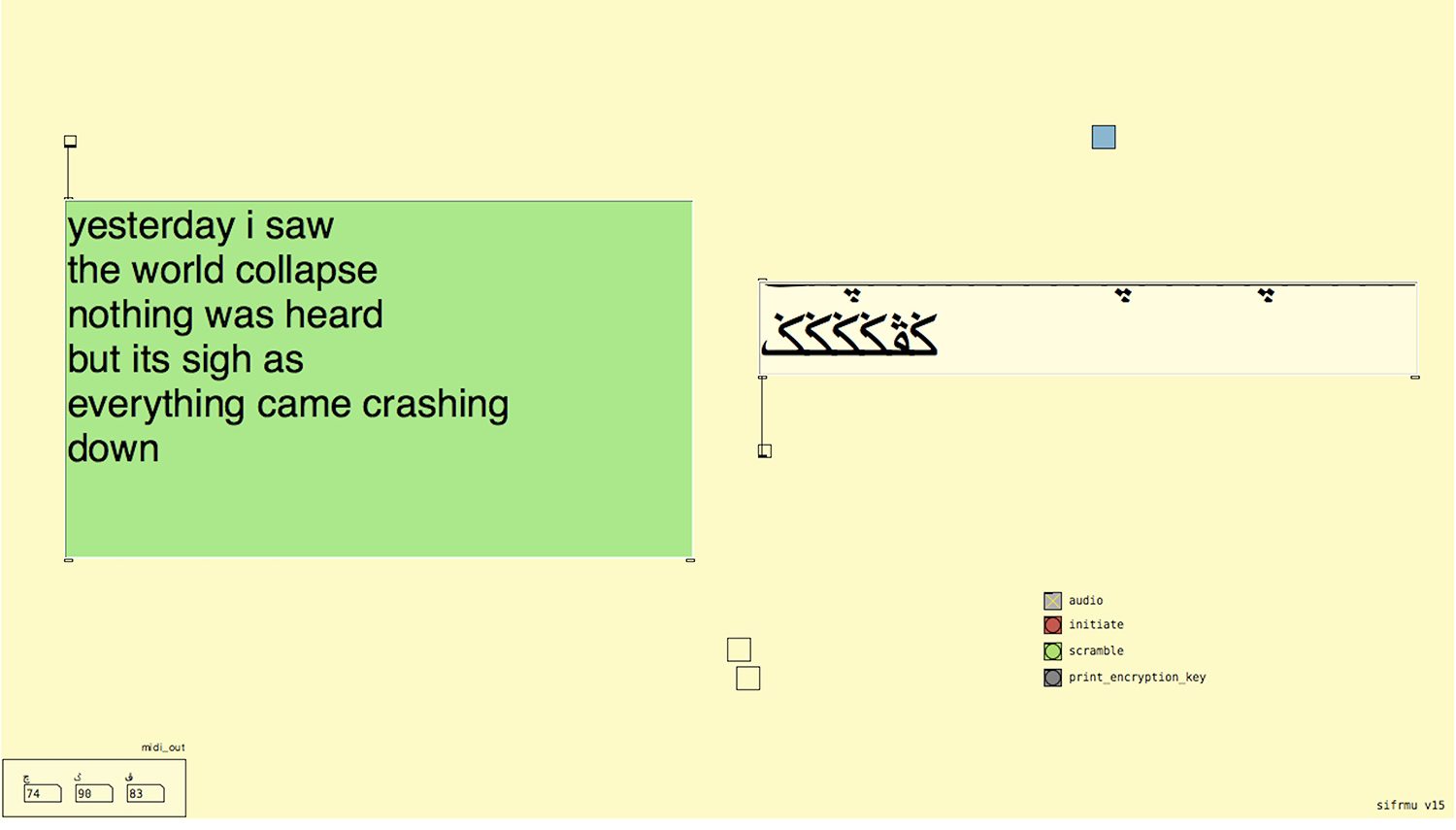

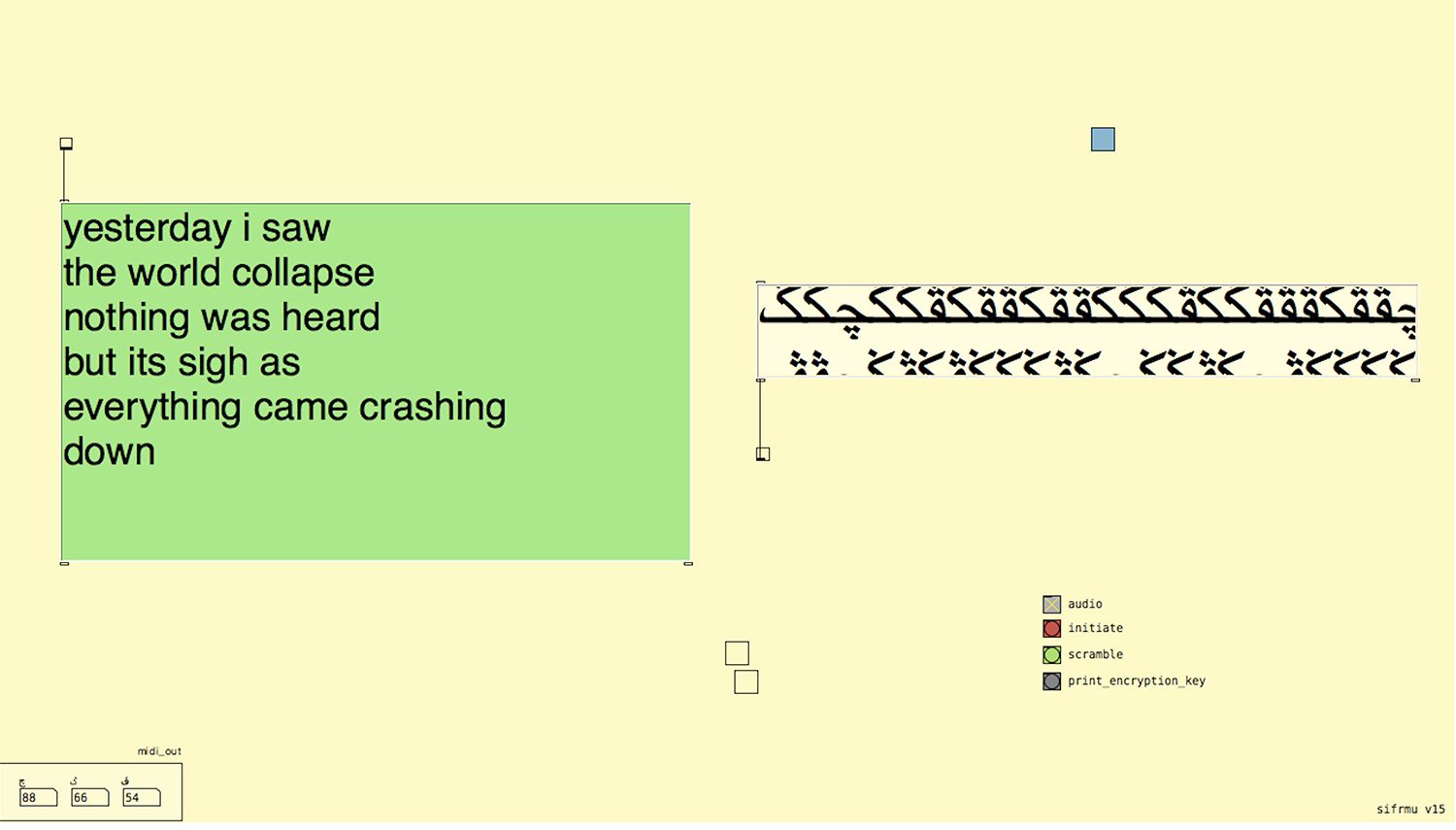

Haykal straddles the worlds of poetry, art, and music, and raises down-to-earth questions about our technology-fueled lives. He remodels “familiar interfaces” such as QWERTY keyboards (mechanical switches) and oven controls (rotary selector switches). He transforms the gear into performable linguistic instruments that the public is invited to operate. The title of Haykal’s project, sifrmu, is a portmanteau of sifr, Arabic for zero; the etymology of the word cipher; and “mu,” a Malay suffix meaning “you” or “yours.” Thus, it is loosely translated as “your cipher.”

Haykal’s sifrmu device encrypts Romanized plaintext into a three-character Jawi script ciphertext. Users are invited to participate by scrambling and generating new encryption keys, allowing for a more dynamic use of enciphering texts. Each stroke is timed to facilitate a more organic interaction between user input and machine output.

Over the coming years, artists will continue to develop new strategies as they wrestle with singular methods and engaging possibilities. Their ideas will reach us in the same way that we breathe, readily and with dignity. As artists come up with solutions for the current chaos, we can hope that art will be more reparative, our interactions will be more personal, and we will have a positive impact on each other. The future will be brighter, regardless of the gloomy vision being touted in so many corners of the world today.