Shall we begin at the beginning? Or, to be more precise, The Beginning (1959)? One of the earliest recorded works by artist Liliane Lijn, this drawing depicts a circular swirl of rolling clouds and mountain-like forms spinning out from a densely inscribed core. Evocative of the mysterious landscapes of da Vinci, the undulating inky waves generate a sense of whirling motion, akin to a planetary orbit. For Lijn, this drawing serves as a kind of urtext, “a cosmic map of her own beginning,”1 confirming a fascination with movement that came to define the course of her seven-decade career.

Born in 1939, Lijn grew up in New York before relocating to Switzerland with her parents as a teenager. At the age of eighteen, she declared that she was going to be an artist and moved to Paris. She opted not to go to art school, studying at the Sorbonne instead, a decision she has attributed to her rebellious nature. Lijn soon realized that the city was neither what she had expected nor hoped for. She found it impossible to be taken seriously as an artist and came across few other women in the field. Despite her artistic innovations and her immersion in the Parisian avant-garde, Lijn felt mostly ignored by her peers, who were more interested in the work of her partner, the Greek artist Takis. During this time Lijn even had her work copied and exhibited, without credit, by the American Beat poet Harold Norse.2

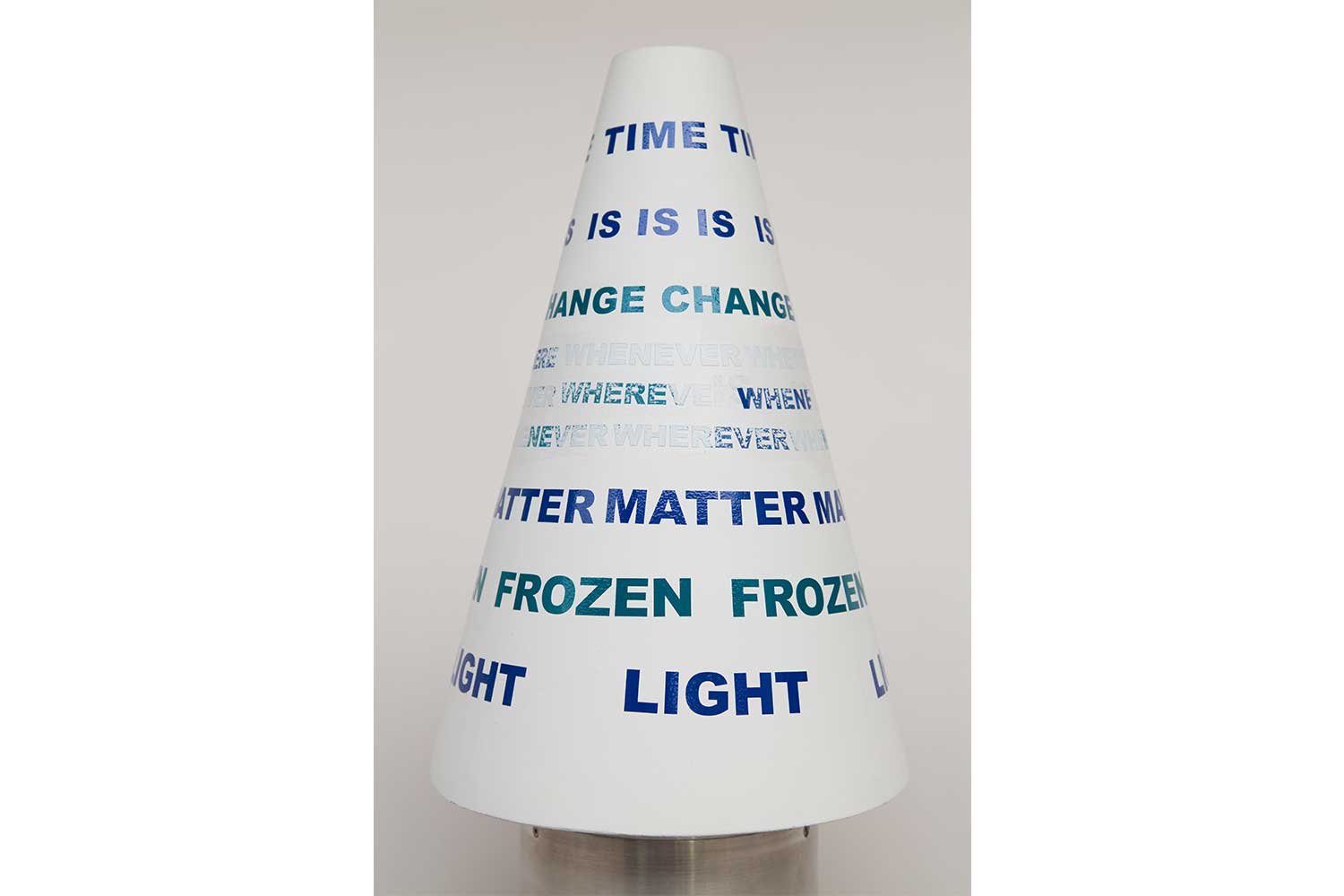

In spite of a lack of support, Lijn continued to produce, pushing her practice in increasingly experimental directions. In the early 1960s she began developing her “poem machines,” a series of works consisting of Letraset lettering transferred to a spinning metal cylinder powered by a motor. At first Lijn focused on the formal qualities of lettering, printing texts in various configurations divorced from their significatory content, in works such as Alphabet (1962). She moved on to reprinting poems, including works by Nazli Nour in Get Rid of Government Time (1962) and, later, her own writing in Man is Naked (1964–65). The motion of the drum vibrated the words, rendering them blurry and, ultimately, unintelligible. Lijn’s poem machines made visible some of the theoretical precepts circulating in Parisian intellectual circles at the time, namely poststructuralism’s deconstruction of the relationship between the sign (or word) and the signified (the word’s content) and consequent postulation that every text has multiple meanings.

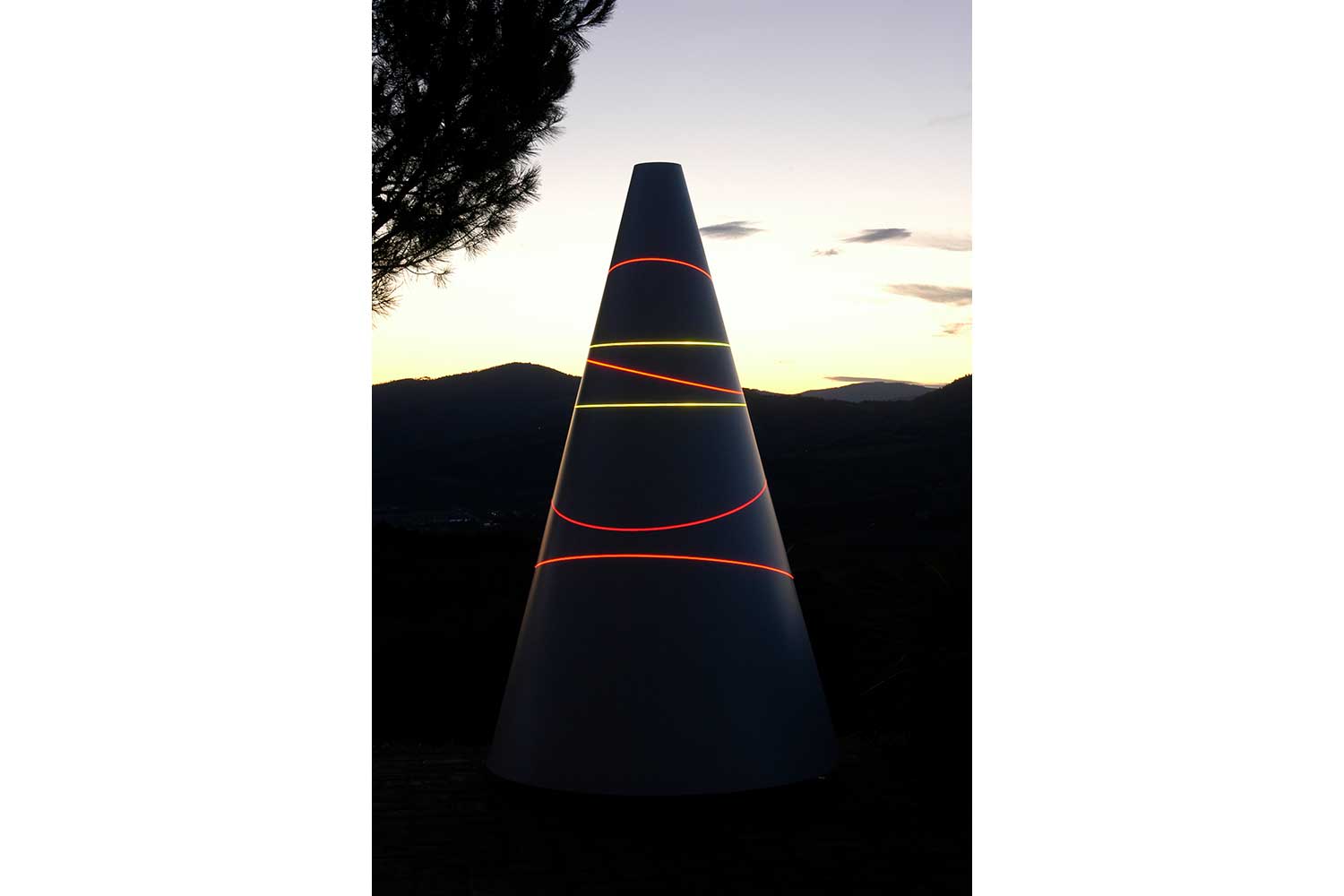

In the mid-to-late 1960s, Lijn’s poem machines evolved from cylinders to cones in works such as Sky never stops: poemkon (1965) and Poemkon=D=4=Open=Apollinaire (1968), and it is perhaps this form that the artist is most famous for. Having rechristened them “koans” in 1969, after the cryptic proverbs of Zen Buddhism, Lijn ended up discarding lettering entirely. She continued to make the koans kinetic, setting them on motorized turntables. They became simpler and more iconic in form, acquiring an almost totemic quality. Lest one be tempted to read the koans as phallic, Lijn has been at pains to position them within another symbolic tradition, stating: “The cone itself is a very important female symbol. It’s not male, it’s feminine. When the koans oscillate, the more you look at them, the less you see the body.”3 By placing the sculptures in motion, she aimed to dematerialize the womanly body4 that had so defined her early experiences as an artist in Paris. Kinetic work served, then, as a form of empowerment in the face of an overwhelmingly patriarchal and deterministic society.

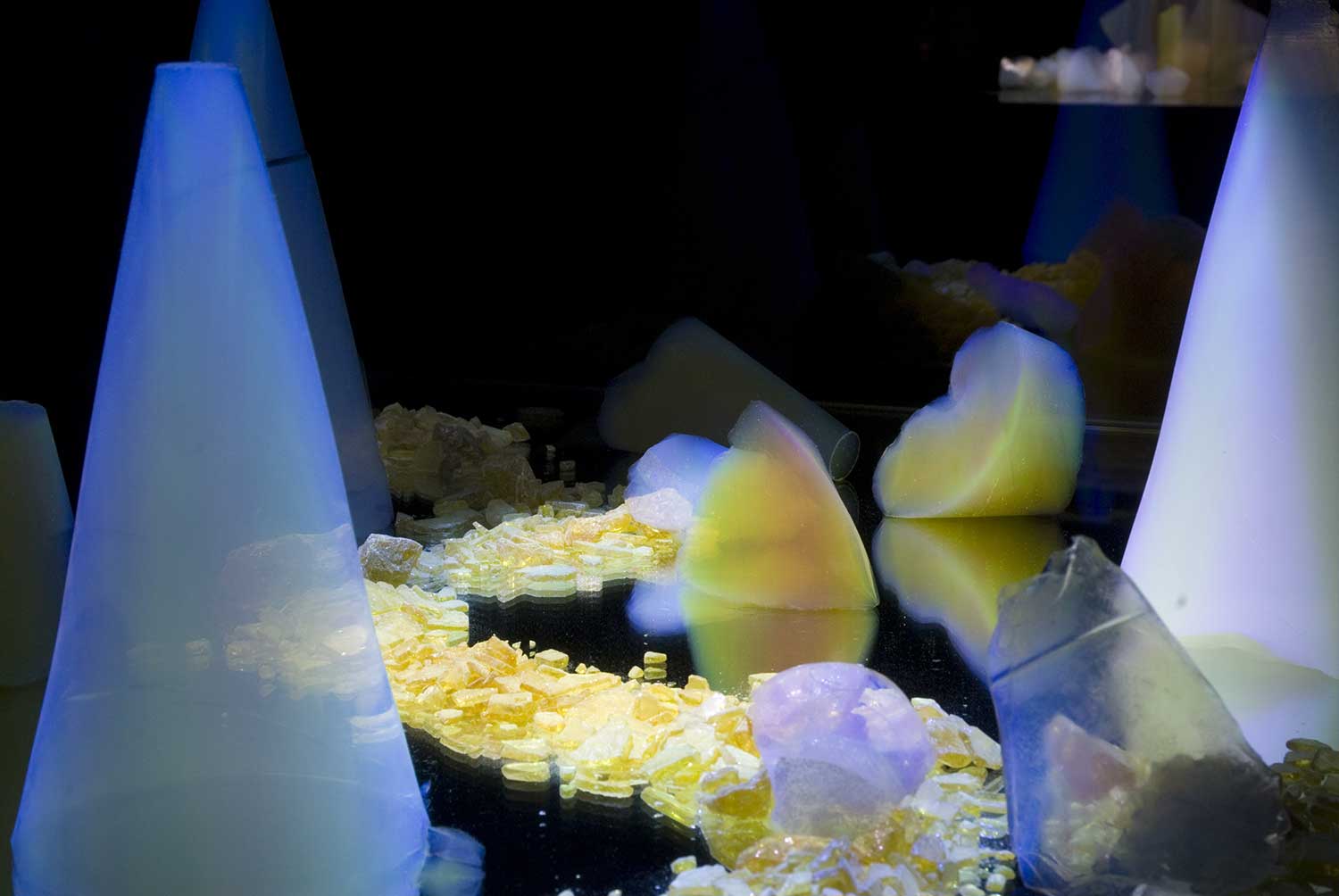

With their exploration of light, the koans and other works from this era, such as Liquid Reflections (1968) and Linear Light Column (1969), a revolving column wound with copper wire, manifest the artist’s growing fascination with science and technology. These works employ industrial materials such as metal, acrylic polymers, and plastic lenses to examine the properties of light and water and the forces of physics and astronomy. The koan itself operates as a prism with a transformative power to render invisible phenomena more tangible. Their continual motion produces an ever-changing reflective surface instead of a fixed shape. This movement transfixes the viewer, producing a moment of deep awareness that allows one to still the mind and see the world anew. This resonates with the Zen concept of mushin or “empty mind,” a conscious flow state in which one remains open and unbiased and, thus, able to see more directly. Lijn has spoken in interviews about her desire to ground the viewer in the present moment, to enable them to experience the same absorption in one’s surroundings as children.5

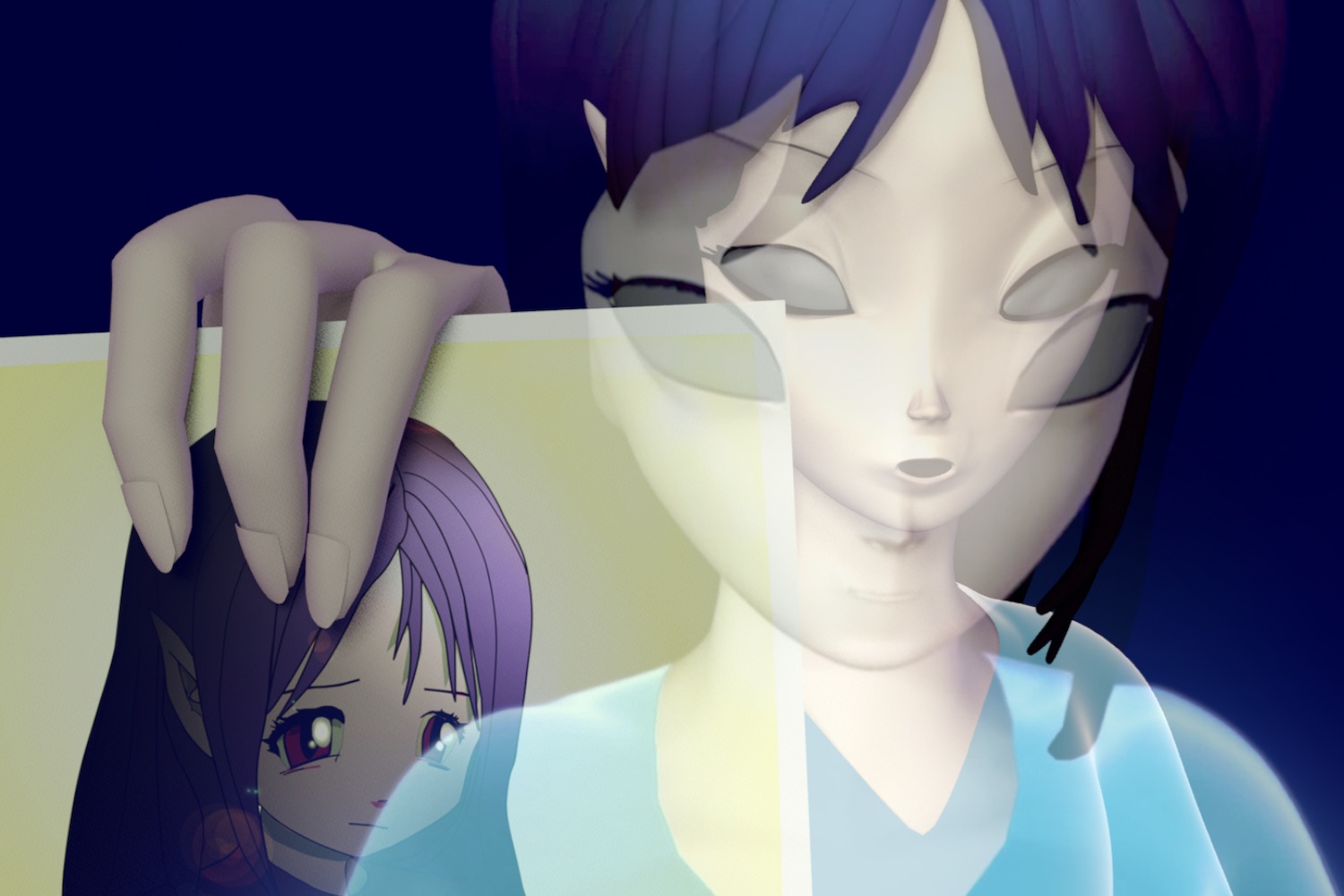

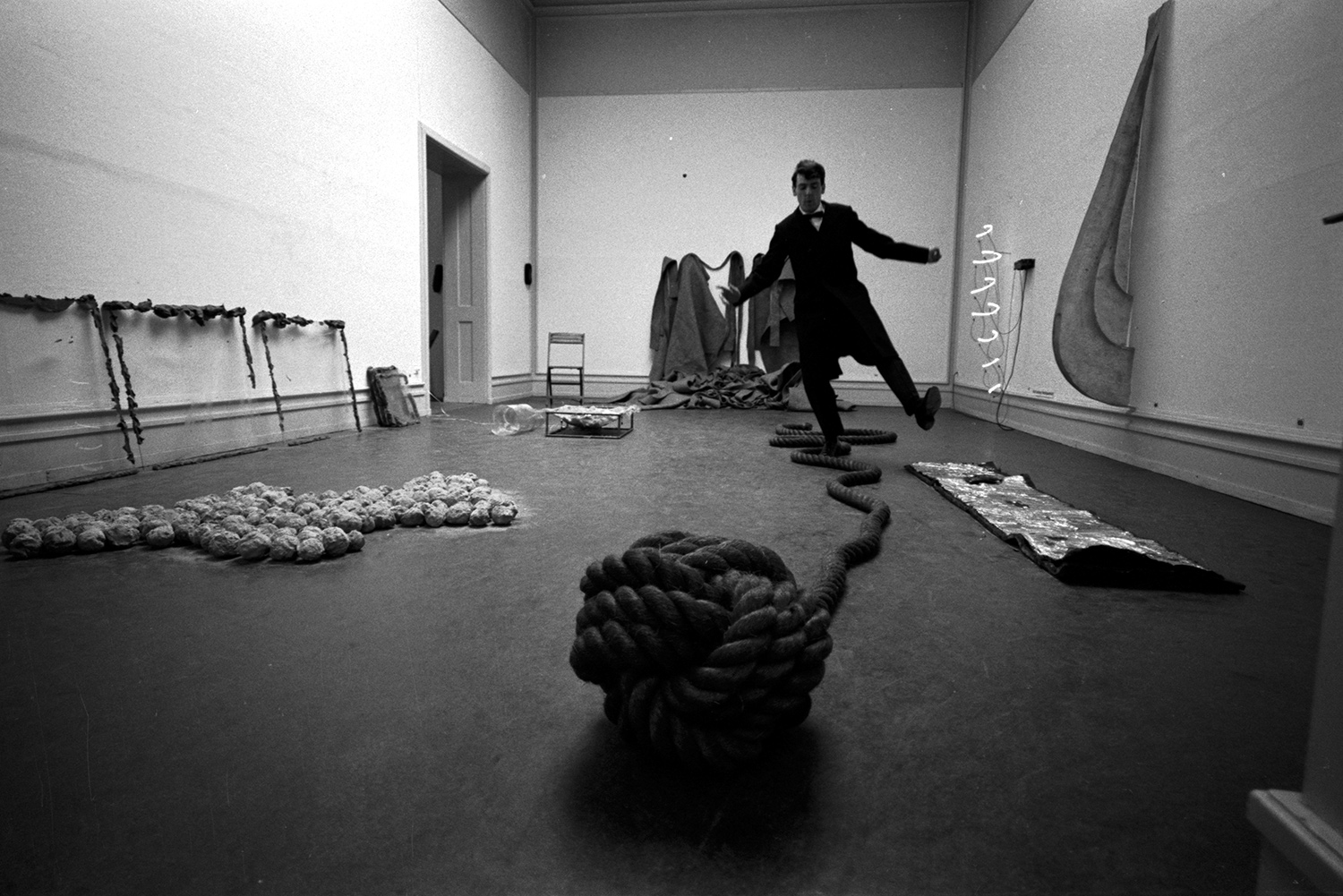

Lijn’s concerns from this time were in step with those of many of her peers, from the formal quality and industrial materials of Minimalist sculptors like Dan Flavin and Robert Morris to the work of California artists such as John McLaughlin, who also employed simple geometric forms as foci for Zen contemplation. Her work also bears comparison to that of Anthony McCall, in the UK, who was testing the formal properties of light through sculpture. In the 1970s, however, Lijn embarked on a new body of work with an entirely different approach. She began making figurative multimedia sculptures and installations that, while still engaged with technology, assumed a more organic, assemblage aesthetic. Works like Woman of War (1986) and The Bride (1988), described by Lijn as performing sculptures, are modeled after goddess archetypes in ancient mythology, offering a counterpoint to patriarchal historiography. She has said of these works: “In reinventing the archetype of the goddess, I wanted to reinvest the feminine with spiritual power.”6 This reimagining of women’s potential is evident in works such as Transformation of the Bride into the Medusa (1987), a work on paper depicting a virginal figure — ordinarily reliant on a male counterpart for definition — who is transmuted into a powerful entity in her own right. Here the simple, cloudlike pastel forms of the first panel evolve gradually as the triptych progresses, culminating in a complex, writhing concatenation of snaky strands.

The artist’s reclamation of a feminist mythology finds kinship in the work of the French-Algerian poststructuralist theorist Hélène Cixous. In her essay “The Laugh of the Medusa,” Cixous draws on the famous myth to reveal the diminution of women by the patriarchy, which renders them simultaneously inferior and threatening. Through her reading, the figure of Medusa is transformed from a monster into a symbol of female power and complex sexuality. By encouraging women to write what she terms écriture feminine, Cixous offers authorship as a means of accessing authority and, ultimately, bodily pleasures on one’s own terms. She encourages women to create as a means of transforming the repressive status quo, to embrace a multiple and fluid sexuality, one that rejects binaries and celebrates the heterogeneity and “infinite richness” of women.7

Many of these threads can be read in The Bride, which will feature in Lijn’s upcoming survey at Ordet in Milan. This dramatic sculpture was inspired by the Sumerian myth of the goddess Inanna’s descent to the underworld and a visit by the artist to an electrical substation.8 Encased in a mesh enclosure, which suggests a need for protection (whether the bride needs protecting from us, or vice versa, is unclear), the figure is dimly lit and further obscured by a steel veil. Despite being unable to see the figure in its entirety, the bride possesses a towering presence, reverberating with energy. Glimpses of feathers and glass, crystalline layers of epoxy-bonded mica and lacquered papier-mâché egg-like forms, connote an alien captured in her habitat. With her intricate construction, this work recalls another famous caged bride, that of Marcel Duchamp’s installation The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even. While Duchamp’s bride is defined by the presence of (and perennial separation from) her suitors, Lijn’s counterpart sits alone, seemingly in wait. While Lijn’s installation is as idiosyncratic and complex as Duchamp’s, her iteration lends greater weight to the bride. Crackling with electricity, Lijn’s bride appears to be on the brink of a pause, her fearsome power idling only temporarily.

In her 2012 exhibition “Cosmic Dramas” at Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (mima), Woman of War and The Bride were installed alongside a haunting soundtrack, written and performed by Lijn. The artist has described how this music came to her instinctively, as if from the earth. Lijn’s desire to sing, and her openness to this intuitive voice, resonates with Cixous’s emphasis on trusting unconscious urges in the creative process, describing “my body shot through with streams of song.”9 Chanting “I am the Medusa, look at me, turn to stone. I’m the image of she,” Lijn evokes an ancient, inchoate female fury. Resembling a kind of techno-charged Winged Victory of Samothrace, these monumental mechanized figures pulse with light and command the viewer’s attention without a qualm.

At first glance, these works represent a radical departure from Lijn’s works of the 1960s. On the one hand, the minimalist form of the koans evoke scientific enquiry while, on the other, the multimedia works privilege poetry and mythology, seemingly belonging to an entirely opposed tradition of enquiry. While the koans, which can be most readily compared to male artists’ work, may at first appear “masculine,” it is critical that we interrogate any assumptions that science = male and body = female. Lijn herself has observed that when she started making art as a young woman, she believed that “being a woman in a sense installed you so totally in your body that you could do two things: you could say, ‘Yes, I am body and I’m proud of it,’ or you could say, ‘I’m mind, forget the body.’”10 With this new body of work in the 1970s, however, Lijn came to reject such Cartesian dualism, which has defined so much of Western thought. Instead, this decade saw Lijn leading the charge encouraged by Cixous: “Write the self and return to the body which has been taken away from you.”11

From the 1980s onward, Lijn’s practice has included both koans and multimedia works. In the former, she highlights the discursive nature of science, emphasizing its poetic qualities and indirectly rejecting its claims to objectivity. Rather than accepting established norms, Lijn insisted on observing phenomena herself, on her own terms. Her kinetic work and the formal multiplicity of her practice attests to her commitment to fluidity, embodying Cixous’s exhortation: “Woman must put herself into the text — as into the world and into history — by her own movement.”12 As an artist, Lijn defies easy categorization. She never participated in any single artistic movement, she never felt pressured to exhibit, nor to pursue an ambitious career — which may well be because she didn’t go to art school. With her rejection of predetermined models, it seems that Lijn’s rebellious streak has outlasted her teenage years. Long may it continue.