Laura Fried: Your compact compositions reveal suspended abstract forms, layered by series of densely pigmented veils of paint. And yet process seems to vanish behind the completed form… What are the character and conditions of the image in your painting?

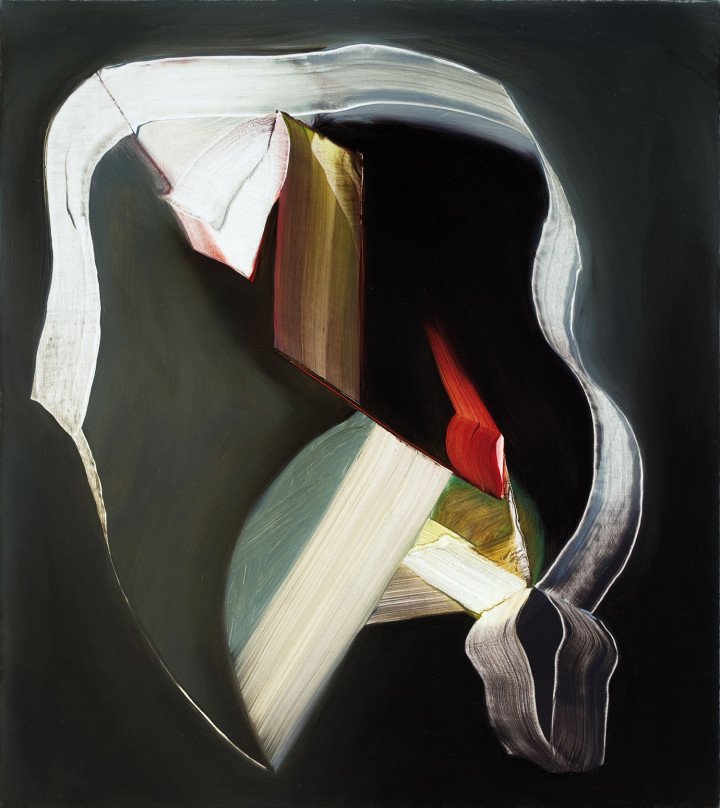

Lesley Vance: My paintings originate from still lives of natural forms composed in the studio: I put together an arrangement of objects from my collection in a box where I control lighting by cutting openings for light to shine through. I’ll paint this image, and once it reaches a certain point of resolution, the composition begins to evolve and I’m no longer looking at the source material. From there the surface becomes a malleable space as the objects dissolve into pure form, although traces from the original image frequently remain in the finished work. Decisions I make either echo or challenge formal qualities from the earlier composition. It’s an intuitive process with a continuous back and forth between spontaneous gestures and cerebral control. The painting conforms to its own spatial principles as it makes its way towards its natural end, which doesn’t happen unless the image becomes its own concrete reality. I hope that in the end, the painting’s shapes, colors and gestures fold into and out of themselves as well as the space they occupy. I don’t want the viewer to trace the steps backward when looking at the work; it is important that the image feels new and strange but confident in its existence and asserts its reality, however awkward, with pleasure and ease.

LF: In your studio we discussed the traditions of the still life genre. What is your relationship to the representational form, which is propelled to real abstraction in your painting?

LV: I have to let the original composition go so the new one can find itself. I think about 17th-century Spanish painters Zurburán and Cotán, whose intense color choices and extreme contrasts nearly transform their arrangements into otherworldly events. In my work the still life only endures as something like the sense you get in certain rooms that exist as you see them when you walk in, but somehow feel like vaults of past activity and objects. Right now I especially love Gris. His paintings are strange and awkward but so elegant. Gertrude Stein writes about him: “As a Spaniard he knew cubism and had stepped through into it. He had stepped through it. There was beside this perfection.”

LF: I’ve noticed your palette has shifted this year; texture has begun to surface at precise moments…

LV: Over the last year paintings have become richer and colors bolder. Color lends itself to the painting’s atmosphere, but I also use color to lift surfaces above others or set shapes back. Expanding my palette allows me to create more depth, and using more saturated colors can produce sharper contrasts of light and dark. Scraping paint from the surface sometimes creates holes in the space to imply further depths, but often the texture from the linen’s weave appears to lie on the surface rather than beneath it. Moments of painterly texture also emerge from the traces of the earliest referential forms that have remained over the course of painting.