Paul McCarthy: When was Tulsa?

Larry Clark: From ’62 to ’71.

PM: Karen and I met in ’63. In ’66, ’67, I’d drawn her in various poses with a view of the vagina. Then I started taking photographs of her. Now I realize she was some sort of muse. But I never thought of that word. I was a young guy. The muse was her, the vagina and a set of drawings and photographs. I’m actually thinking of that period a lot.

LC: I never used the word muse either, but people now say that Jonathan has been my muse. I have all the photographs and I’ve made a film; I’m going to make another film and I’m doing the sculpture; it’s like: How close can I get? How close can I get you to that person, to be that person, to be that age?

PM: You said Jonathan’s your muse?

LC: That’s what people say.

PM: Is Jonathan also Tulsa or is that you?

LC: I think it’s also me, it’s also Tulsa. It gets very abstract. But not just me, nor just Jonathan. I’m trying to get something in there that’s not just what it appears to be. It’s not just documents at all. I want it to appear just documents but it’s a lot more than that. It’s very strange because I’ve had people write that the work is very creepy, that I’m sucking the life out of these teenagers. They’re trying to put me down, but sometimes it comes very close to that; to the desire to just hang someone to the wall!

PM: But you give them something. In every one of these films, people walk away with something. Some walk away with big prizes. Some walk away with careers. If you make a movie, the question might be, are they ready for it? They’re so young, they hardly know what’s happening.

LC: It’s changed so much now; they’re so aware of what’s going on, more than they used to be. When I was taking pictures in Oklahoma I didn’t know what I was doing and the people didn’t know what I was doing. Now everybody is very aware of it.

PM: At 18 years old, you’re aware but you’re not…

LC: That’s true. But in this context, it’s obvious that I’m making their world much bigger. I give them many more opportunities, whereas their world might be a couple of square blocks. I can’t say that I hurt anybody.

PM: There is a voyeur aspect. A bit of your voyeur in their world and you watch them.

LC: I think my audience is a much bigger voyeur than I am.

PM: Really?

LC: Maybe not.

PM: I mean you’re a chooser. You seek it out and you choose it and then you watch it.

LC: In the early work I was a part of it. In Tulsa I was part of the world and I was photographing myself and my own life.

PM: Tulsa was a document.

LC: Yes, a straight documentary. At that time, people were very excited to live that life from looking at my work; that was voyeuristic because they didn’t have to live it, but they could live it through my work. But maybe the later work does take on a more voyeuristic quality because it’s not me. And I’m an old guy doing this stuff.

PM: It’s like recreating Tulsa. Do you long for it? I don’t think my work is about longing for the ’70s. It’s not the ’70s that I long for. But, I remember I was talking to Kristine Stiles once and she was going off on me and said that all this that I was creating — all this stuff where I’d wear a Madonna mask or another kind of mask and then talk about it in terms of architecture — none of it matters. Essentially, that my work is latent behavior, that somehow it’s about oppression. That it’s all the same and I just decorate it with this other stuff. Your work has groupings of teenagers together, all going through some sort of journey. Each film has the same initial structure as Tulsa. And there’s a repeating of that. You could say Ken Park is different from Wassup Rockers, or Kids is different from Ken Park, but in a way, it’s all the same. You repeat the same thing. And that’s kind of what she was saying to me, and it’s true, although there are other complexities.

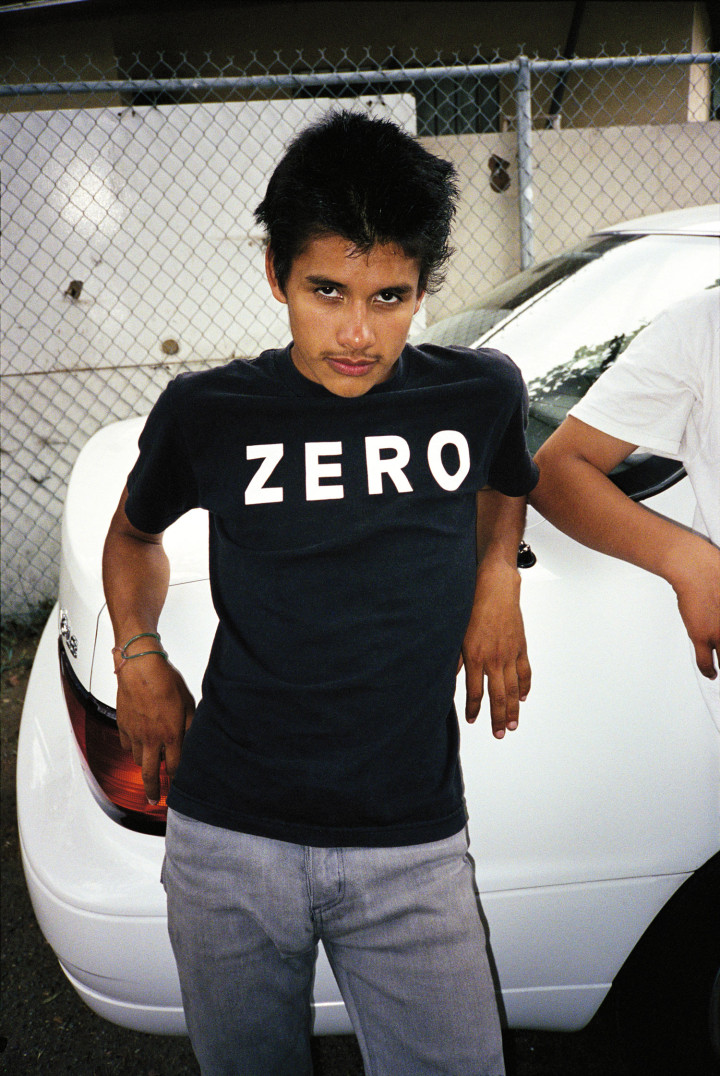

LC: In mine it’s always a small, isolated group of people that you don’t see otherwise. Like you’ve never seen the people in Tulsa or the Latino kids in Wassup Rockers in the ’hood where only blacks and Latinos live. You never see these kids. It’s not about longing at all, to me.

PM: Have you ever done a film or work of another period or time? I mean, have you ever considered a period piece?

LC: Well, Another Day in Paradise was supposed to be about the ’70s. But it wasn’t like a really different time. It was coming out of Tulsa.

PM: But another historical period is not something that you are interested in?

LC: You mean going earlier, like before I was born? It could. That’s a good idea. But I think that Tulsa was so real because it was a document. But, instead, Kids was a scripted piece with acting and a lot of people came out of the film really pissed off thinking it was a documentary. It’s interesting because the last thing I did for Flash Art was a talk with Mike Kelley [“In Youth Is Pleasure,” Flash Art International # 164, 1992]. Mike and I talked about Tulsa having this fictive quality to it. It was real but with a fictive quality.

When I made Kids, I turned it around. It was fiction but had a documentary quality to it. In Tulsa, I was making friends into movie stars. I was photographing that instant when they were doing what they were doing but the lighting was good. I was making a movie with real people living real lives. I recognized the drama that light and shadow cause and did something with it, when most photographers would have thought it was ugly. A documentary photographer would have made everyone ugly, focusing more on the action than on the people. I was more interested in the people than in the action. My friends could be murdering somebody but I was making sure they looked good doing it.

Basically what Kristine Stiles was saying is that we all have one story to tell. You are telling one story, but it’s what most artists do. It’s who you are. It’s very interesting to see your piece with you fucking a pig and then Bush’s head…

PM: I made this piece, called The Train, where eight figures are behind a pig and it looks like a train. Then I made a rubber one where the head turns, the eyes and mouth move and it talks to you. A figure is fucking the pig and a little pig is fucking the eye of the big pig. When you enter the room the heads will follow you. It’s a complicated animatronic figure. That piece still has a straight-on view. The bodies melt together where the little pig’s body is part of the big pig’s and the Bush character now has three heads. One head is a pig’s head. I also want to make sculpture that people can climb up into and get inside them. There’s something about that which goes way back to somehow getting inside the body. The mask is not just a mask. It’s a head inside a head. These structures are in one way formal, but in a way they’re also very psychological. In the architecture of the body, being on the inside and being on the outside… Yeah, I want to translate the sensation of rubbing a penis, but it’s more than just that.

LC: I’m trying to get inside of these people. With your work, I start tripping out on it poetically, about life. It can also be very political because I can read that into it. You’re bringing out emotions and feelings and thoughts that can take you many places. I’ll see your work about Bush and the pirate, and it just gets into how complex life is and what humans are capable of doing in the worst sense. It’s really overwhelming to me.

PM: A few years ago I was using things like Santa Claus and Popeye as cultural fabrications. Santa Claus is a cultural fabrication, like Mickey Mouse. When I decided to do the Piccadilly Circus piece, somebody asked us how it worked. I said, “I’d like to shoot a movie in this weird building, a bank.” They said, “You can do it, but you have to do it at night.” But when we were sitting there, they said that the upstairs room is called the American Room, in this British Bank. And we asked why it was called that and they said that Bush was in the top room and Bin Laden was in the basement. And I said, “and the Queen is in the middle.” Suddenly the structure was set up. At first I thought I didn’t want to deal with that: George Bush at the top, Bin Laden in the basement and the Queen in the middle.

PM: A few years ago I was using things like Santa Claus and Popeye as cultural fabrications. Santa Claus is a cultural fabrication, like Mickey Mouse. When I decided to do the Piccadilly Circus piece, somebody asked us how it worked. I said, “I’d like to shoot a movie in this weird building, a bank.” They said, “You can do it, but you have to do it at night.” But when we were sitting there, they said that the upstairs room is called the American Room, in this British Bank. And we asked why it was called that and they said that Bush was in the top room and Bin Laden was in the basement. And I said, “and the Queen is in the middle.” Suddenly the structure was set up. At first I thought I didn’t want to deal with that: George Bush at the top, Bin Laden in the basement and the Queen in the middle.

I realized these figures where Bush and Bin Laden are almost cartoons, almost fabrications. They’re almost not real. In a certain way they exist in a cloud zone. I said to someone, “They’re no different from Santa Claus and Mickey Mouse.” You can’t help but feel this hopelessness. We are in a spectacle controlled by a spectacle and George Bush is a cartoon within it. And you’d think, “Well, just change the course of the spectacle.” But is it really going to change? This is what that piece is about.

But, to go back to my question about the period, I was only interested in the period, I’m not interested in a period piece. I’m interested in appropriating a period. It’s almost like a film about Hollywood. By appropriating a Western, it’s political. I think that a discussion about Hollywood is political because Hollywood is so much a part of Western colonialism. In one way, it’s like critiquing the art world and critiquing Hollywood and critiquing Bush.

LC: Well, a lot of the art world is like Hollywood and like Disney. It’s about the product.

PM: It’s like that piece with the man in the chocolate factory, turning a gallery into a store. An interesting thing with you is that you do have a real foot in the art world, in the photography world and Hollywood.

LC: It’s always about the work. It’s certainly not about money. One thing I like about you is that the money that you make goes back into the work. You’re spending more money on your work than you’re making. And you’re able to make bigger and bigger work. Whatever’s in your imagination you’re able to realize.

PM: I don’t know how I got here.

LC: I don’t either. I mean, I was a photographer and I was fucked up; I was dying and I couldn’t do anything else. The only thing I wanted to do was to make a film. And I cleaned myself up and changed my life and my image just to be able to make a film, and you’re doing that to build a town. It’s all about that.

PM: You do a show, a film or a sculpture. Do you have hierarchies? Is one larger than the other or is one more critical to you?

LC: It’s more about what I need to do at that point. It’s all hard, but film is extremely hard because there’s so much money and so many people involved, so many things that can fuck up as they always do and then it’s a struggle to fix it. It might take ten years to make a film but I need to do other things too. I can’t just do that.