Aaron Moulton: You trained as a painter at the Royal College of Art in London but your work branches out into everything from painting, sculpture and drawing to different genres of performance, not clinging to one medium. Where do your ideas best take shape?

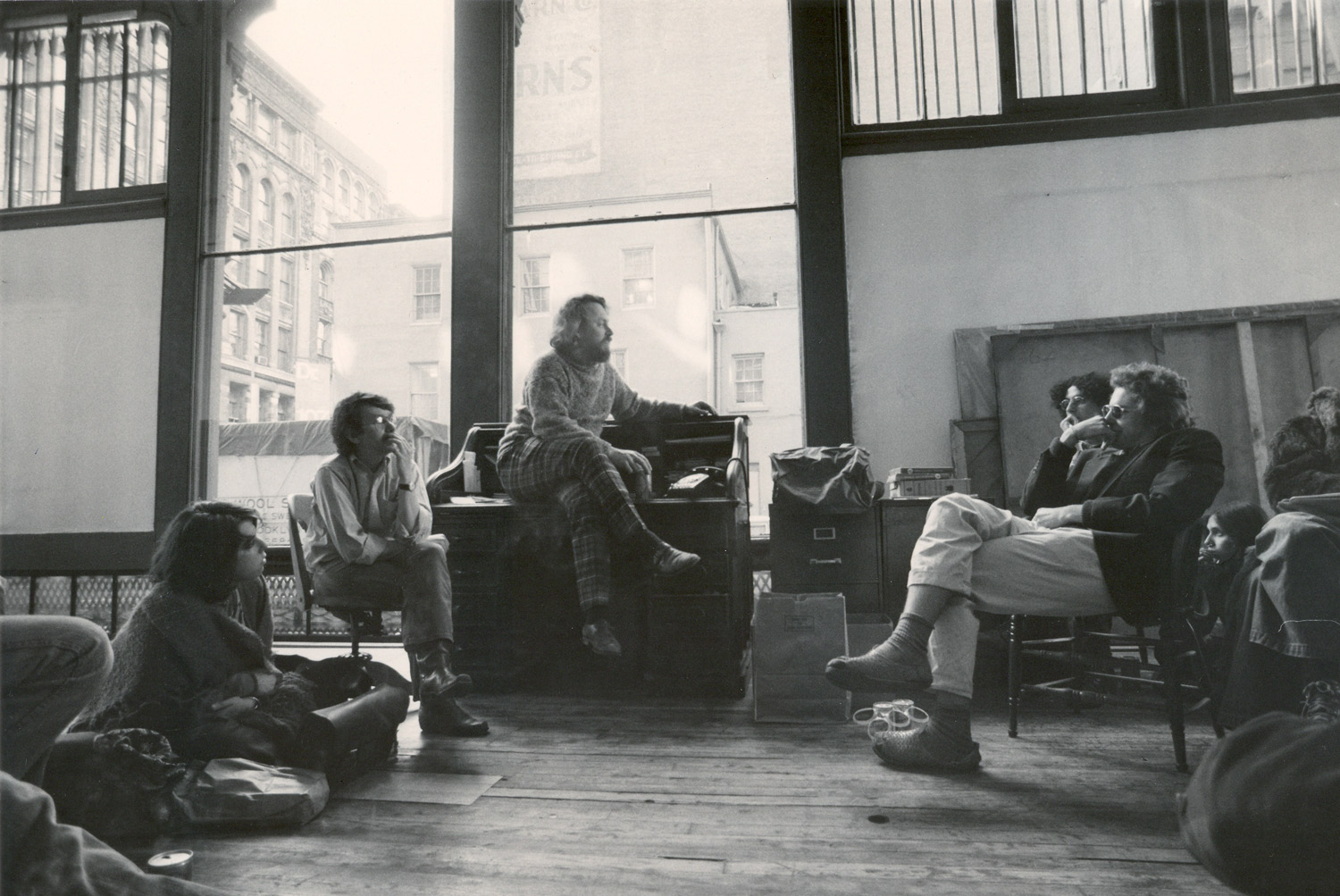

Lali Chetwynd: I have different practices and it’s important for me to balance out the pressures of each one. Working to make a performance happen means working with lots of people plus the physical work of the prop-making and costumes. It takes me about a month to prepare for a performance; after this I’ll take a couple of months to do painting. It’s a relief to have quiet time making work that only relies on me being in a small private space with a box of paints. I wouldn’t cope if I only had one way of working. Being closed away as a quiet painter year round would drive me mad.

AM: How do you become interested in subjects like bats, different interpretations of a religious story, classical and pop mythologies and then treat each with the same amount of investigation? You use subjects as more than a muse but a medium that produces its own body of work.

LC: Ideas come to me “out of the blue,” William Blake-style. If I get excited about an idea then I try to be as logical as I can to execute it. It isn’t really thought out or calculated, it’s more like over excited enthusiasm. After the fun-inspired flash, I make drawings and plans. Also I check with the friends in my troupe if they like the sound of it. I seem to work with the idea of rehabilitation or translation, something completely out of fashion now, not of interest to mainstream cool that I think is worth singing and dancing about. Meatloaf or George Stubs or Yves Klein are some examples. The more I research the more I find myself thinking they have so much fantastic material here, why don’t people appreciate them more… it’s slightly a case of loving the underdog.

AM: And with something like the bats…

LC: Who are always given a bad name in culture.

AM: Did you see the bats leading into the Bat Out of Hell performance from Liverpool in 2004? Even when looking at your paintings, they always seem like studies or parts of something larger.

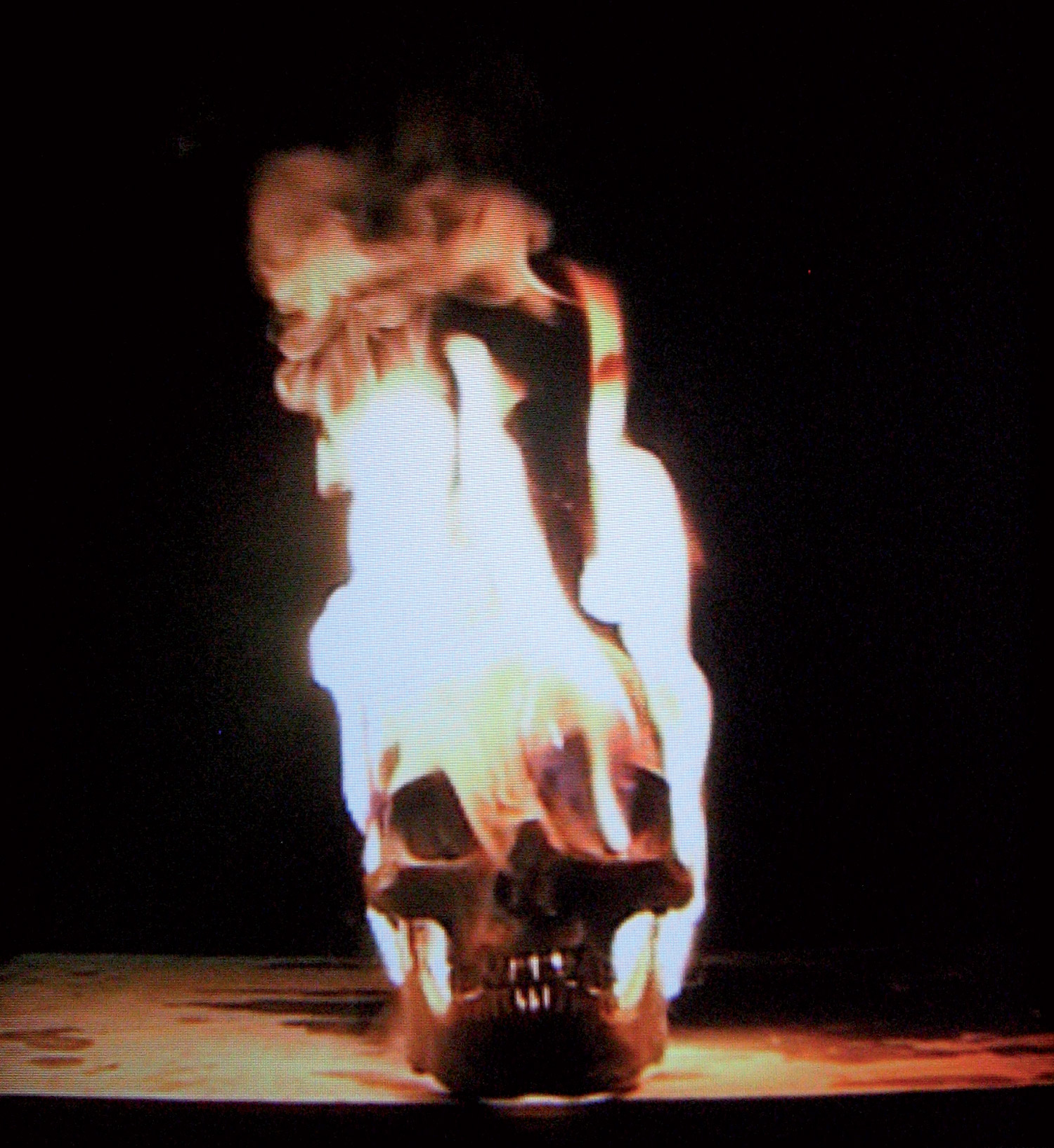

LC: If you mean did I see the original bat project developing into Bat Out of Hell, not really. To tell the truth, I found a fantastic book in the zoological section of the University College London library which had amazing portraits of bats. The photographer had mounted his photographs of bats against these stunning turquoise blue backgrounds that totally reference Holbein. I wonder if the photographer realized this, or whether it was subconscious. So they end up in an odd way looking like formal miniaturist paintings from the 1600s or Francis Bacon’s Pope paintings with the really chewed-up faces. The little bats have this ugly appearance, looking like pompous people of authority, slightly deformed yet also bulbous and snooty. I had a quick recognition when I looked at this book that I could use them as comic anti-heroes. That classic tension in painting between repulsion and attraction… Within painting discourse this can be dubbed simplistic, but for me, this makes them great subject matter — intriguing, repulsive, yet anthropomorphic qualities and a history of being associated with evil. So in this case, the zoological photographs began it all. I knew they’d be good painting subjects because the photographer had already made the jump.

AM: You seem to move away from traditional materials moving between nylon and latex, and painting for example.

LC: Yes, when I studied Social Anthropology I came across Levi Strauss’ definition of bricolage (from “The Savage Mind”) as an unorthodox way of working. He uses the term to describe an approach that is ‘hands on’ or intuitive. The bricoleur does not use formal tools appropriate for a specific task. Instead you grab whatever’s at hand and collage it together. I think I am especially experimental when it comes to materials for performances… Recently I have been interested in using muslin, ink and starch paste to make top hats. I always use a lot of cardboard and latex, and I couldn’t live without my glue gun, and I recently had a breakthrough with plumbing piping.

AM: And when constructing a performance, linking together these totally disparate subjects, how do you form a narrative? They often feel well thought out, but still random.

LC: This is the best way to describe them. I research them heavily, but at the same time there is completely random association. There’s a little bit of Hokusai’s octopus, next to the Emperor Nero’s sex life, next to Meatloaf’s Bat Out of Hell. In trying to get a balance of what you are presenting, the cultural references should be jarring but also self-referential enough for someone to make the associations and yet also enjoy the obvious juxtapositions. It’s meant to be read quite easily like the way people dissect advertising.

AM: You also make these playbills that help give the audience direction.

LC: The booklets give the original source material, for example a section of text from the book that I’ve researched or images. Also it’s really important to give the credit list. I’m pretty sure the secret to collaborating is giving full credit to the parts that make the whole.

AM: In terms of the performances there is a definite amateurish quality. Could you talk a little about who the participants are and what the preparations are for the execution?

LC: I guess the main thing is that the performers are not professional. Most of the performers are friends, family or people who I’ve met out dancing in clubs. The casting is important. It’s important for me that the people that turn up can see how the costumes are made, and the effort that has gone into them, but also to see that someone’s been cast really well. That might sound bizarre, but if, say, someone looks disturbingly like the Hulk or makes the most fantastic poodle in their physical shape, and is also really willing to do it, someone in the audience could pick up on that and enjoy it. So yes, casting is important because there is a sensitivity to the role that each of the performers play.

You can pick up on the feeling that someone’s excited about doing what they’re doing, like being in a poodle costume. It is important that there are some subtle and well thought out aspects to hold it together.

AM: Since there is usually only one rehearsal, a lot of the role-playing seems left to intuition. There is an interesting slipping between the role and self-consciousness within the role…

LC: Yes, this comes from Brecht’s theater in the round, where you don’t suspend belief, the difference of changing in front of someone and stating that you are now representing a role. Someone saying, “I’m going to be the old woman” and putting on the costume in front of the audience is the same as a performer being in character and then pausing to sip a beer or check their phone. I use simple structures to lay out a pattern for performers to work within. These are ‘hooks’ offering something to hold on to within the performance, such as a square drawn on the floor; the performers know that within their expressive ecstasy, when the music changes, they should get to the next corner. There’s a balance between giving them enough information so that they feel like they know what they’re doing but not so much as to take away improvisation and cause the need for more rehearsal.

AM: You tend to use the audience with a notion of active spectatorship, engaging far beyond them merely looking. How does that relate to something like The Walk to Dover which is disengaged with no audience at all?

LC: It really was a case of the romantic gesture of leaving the city and walking into the countryside. The audience participation could be in following the Walk in their mind’s eye, the romantic notion of knowing that we were walking. Similar to the land artists, it was like leaving the gallery. Anyone could have joined and walked with us. One group of kids on bikes got down on their knees and gave us “Wayne’s World” salutes as we walked through their estate. The crucial part of the work was really the actual walking. I realize now, if I do anything like that again I will bear in mind that you don’t need any sort of performance, it can be totally ephemeral, like a gesture.

AM: With Dover you were separating yourself completely from the safety of the art context, and then suddenly you’ve passersby, people in their cars… In a more formal setting, for instance what you did with Cousin Itt in The Walker Gallery, Liverpool, giving guided tours to an uninitiated and uninformed public, wasn’t there a certain unpredictability to the situation?

LC: I thought I had hedged my bets by using someone like Cousin Itt. He’s meant to be a hit with the ladies. You know, to be set at ease, because he’s so comic, he’s all hair! Similarly with Jabba, when I look at him he is a lovable monster. Not menacing in any way. His little grim mouth is ridiculous. In my opinion Jabba and Cousin Itt are real communicators!

AM: With Jabba it was quite a particular situation as you were hosting a forum for talking about world politics…

LC: Yes, he is meant to be talking about world affairs. The human language he knows is Farsi. The incredibly sexy female who translates Jabba’s Farsi into English is the Sunday Times correspondent for Iran. To be honest I seem to have a natural link with a non-art audience as I use source material that is from popular culture. When I was at college, the people who went crazy about my work were the security guards. What is an uninformed audience anyway? I don’t think you need to be art educated to be able to analyze advertising. It’s a normal enough part of anyone’s day-to-day skills

AM: You get your audience to somehow be in character, whether it’s the guest of a to0ur, or the participant on a round table on world politics. With the Iron Age Pasta Necklace Workshop (2005) at Artissima in Turin you were shattering social hierarchies by humiliating collectors with your characters. There is a definite softening of the austerity of a subject.

LC: It’s a case of trying to make something that’s erudite and academic, and out of sight, completely within reach. Cousin Itt gave an informed (though translated) gallery tour on George Stubbs. I am trying to make things like the delicate Roman jewelry in the British Museum accessible, totally goofy and fun, and interesting, disseminating information but hopefully not in a condescending way and also not in a way that is totally recognizable. The problem is, like any format, once it is recognizable it slightly collapses. It’s like that classic Simpsons line when Marge Simpson says, “I’m just afraid of the unfamiliar.” It has to have that slight quality of unfamiliarity to be intriguing, to allow people to let down their guard and be involved and engaged. I am using lots of established patterns definitely, but also looking at what’s of interest at the moment, such as trying to locate a gap between traditional theater and carnival. Maybe it’s the fact that the art world has had a lot of physical body politic performance and now it’s welcoming artists that are using theater as their research source. I’m focusing on what I think is interesting at this moment, but not in a calculated or cold way. It’s more intuitive.

AM: Are there any other disciplines that you would like to incorporate in your work?

LC: I’d like to improve my pattern-cutting skills. I’d love to make and wear my own medieval clothes for a whole year. I’m also changing my name to Spartacus Chetwynd.