There is something rotten about the old ideal of sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll. Attending a concert of Lady Gaga’s Monster Ball tour proves it beyond any possible doubt: the first part is performed by a New York band named Semi Precious Weapons, whose lead singer explains how it’s all about “motherfuckers,” “fucking New York,” “Champagne” and “doing sexual favors.” Dressed as an ambivalently sexualized entity, he walks and dances on high heels, trying to express his metaphysical Dionysian energy. The problem is, it just doesn’t work. It all looks incredibly fake, and the whole pattern of a “rock star” that he seems to follow looks nothing but sadly exhausted. The only moments when he was able to provoke the audience’s reaction, during the first part of Lady Gaga’s concert in Paris, were precisely when he mentioned, shouted, invoked the name of “his Lady.” His stage performance did not represent “an event,” so to speak; as the philosopher Alain Badiou would put it, it was something that exists per se. Therefore, Semi Precious Weapons’ difficulty in reenacting the ideal of the rock ‘n’ roll ethos may well embody the very end of that form of performance.

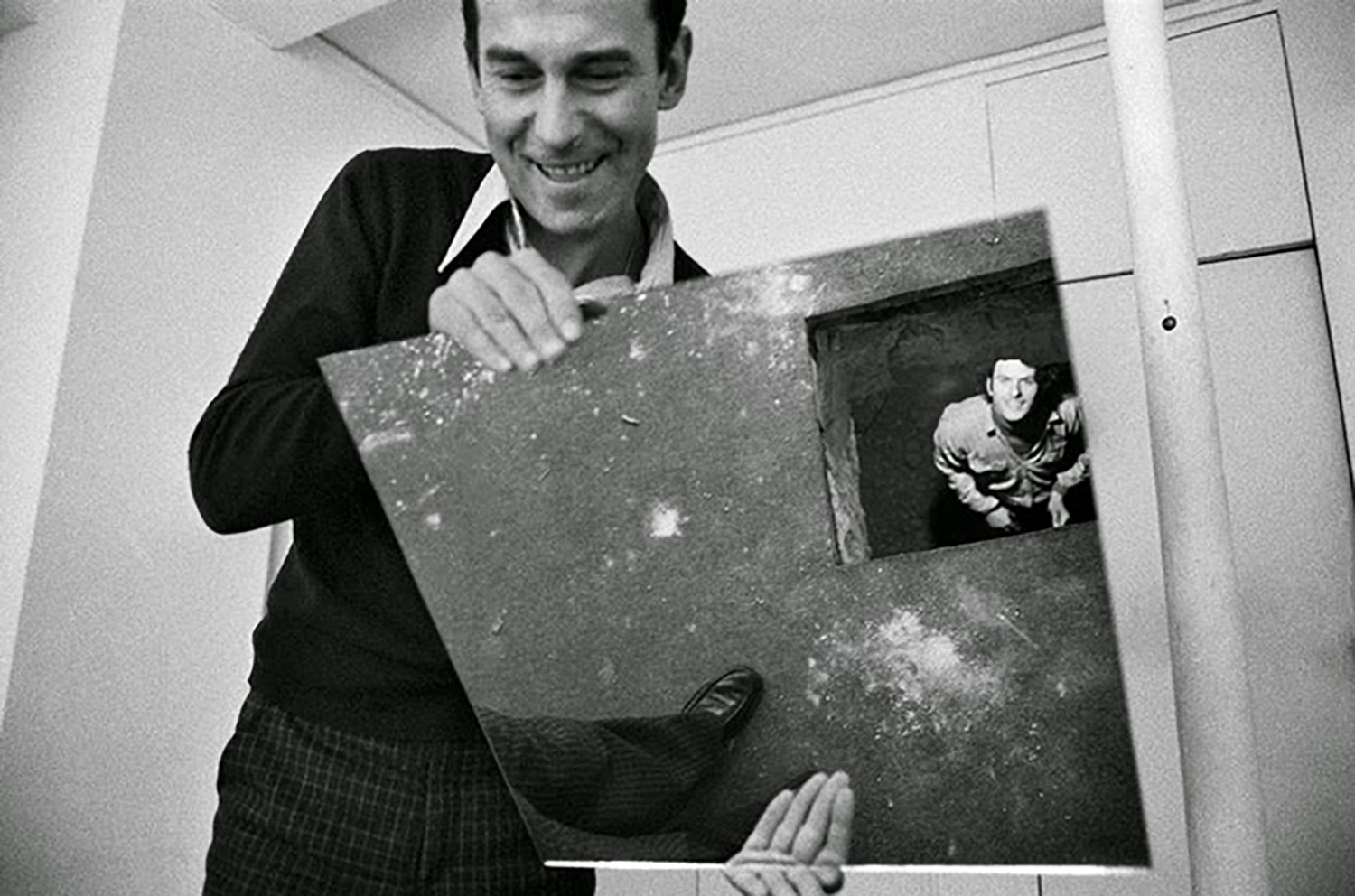

Rock ‘n’ roll is dead — that painful reality needs to be faced. Even the Rolling Stones are becoming older and older… Hence the need to reinvent musical culture. And Lady Gaga has found an efficient and creative way to reshape it: by connecting it to contemporary art. Indeed, she has collaborated with contemporary artists such as, most notably, Francesco Vezzoli, with whom she did a performance at L.A.’s MOCA in 2009, inspired by Sergei Diaghilev’s Les Ballets Russes; Damien Hirst, who designed the piano she used then; and Terence Koh — she has been part of his famous “Terence Koh Show” online, and he has designed a piano for her as well. It appears fairly obvious that she relates her activity as a pop star to the medium that is becoming a mainstream form of contemporary art: performance. As a consequence, she is redefining the meaning of the word, from the common syntagm “a musical performance” to “performance art with music” — or, to use her own words, “pop performance art.” That expression is in itself incredibly significant, as much as it is ambiguous. “Pop performance art” can be understood as “pop performance/art,” i.e., the art of a pop performer, that is to say a pop star, or it can be interpreted as “pop/performance art.” There once was a “pop art” that was supposed to reframe art by taking into consideration the impact of popular culture; now, there would be a “pop performance art” that would propose new perspectives for performance itself. In other words: Is Lady Gaga the Andy Warhol of performance art? And is there in her work the same ambivalence as in Warhol’s duality: an extreme association between visual energy and insights on deep philosophical questions?

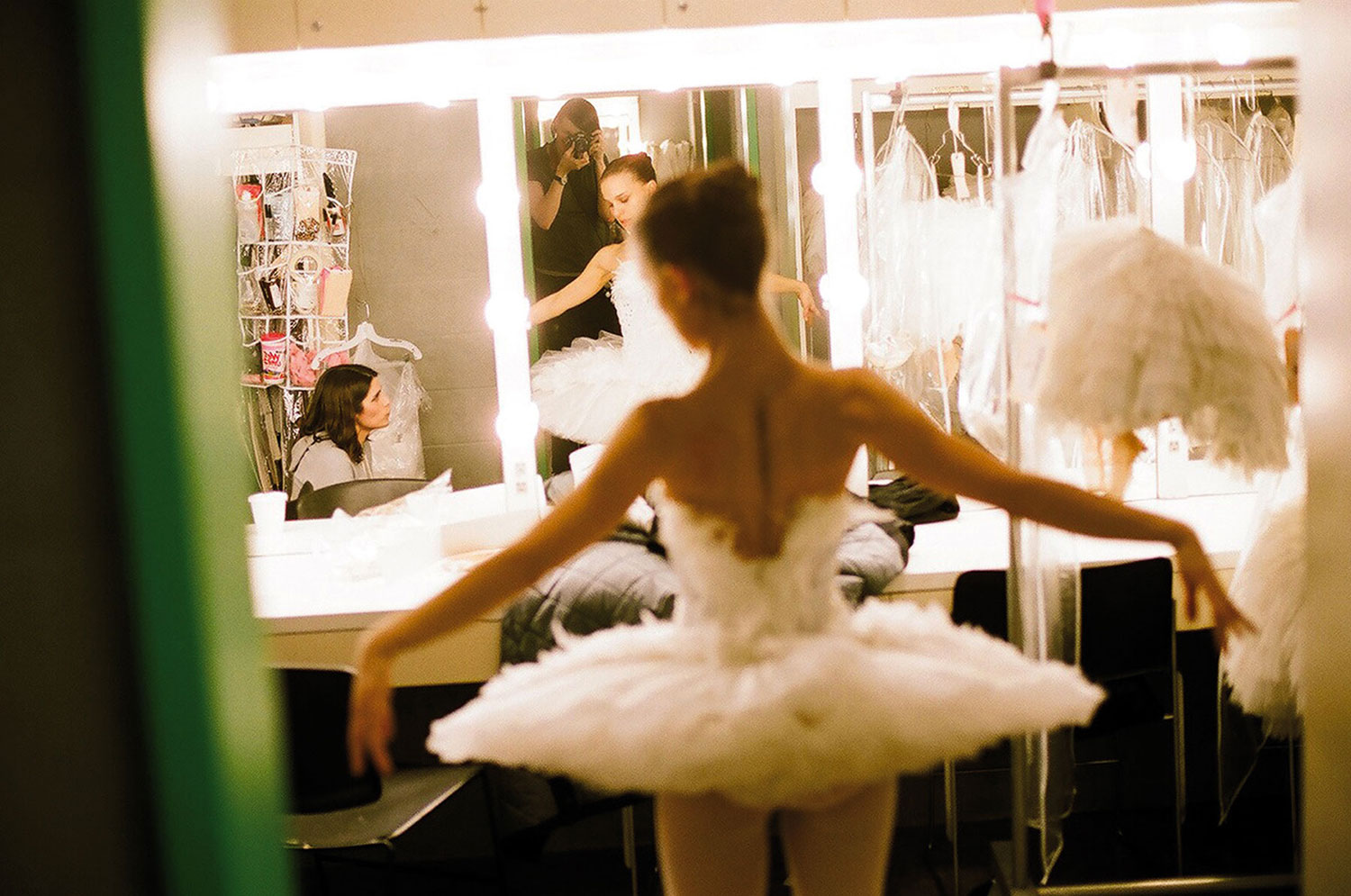

The very concept of “pop performance art” would be impossible if it weren’t formulated today. As such, it is the perfect form of “contemporary art,” a creation of a certain time period. Indeed, since “The Artist Is Present,” Marina Abramovic’s show at MoMA, performance has probably become, in its own way, the most popular format for art. In New York, everyone does performances: waiters in cafés do performances during the weekend; models, when it’s not fashion week somewhere, do performances as well. And the unique success of “The Artist Is Present” epitomized and made visible this revolution inside the art world. It’s not by chance that, when asked about “the limit,” Lady Gaga cites Abramovic as her main inspiration, as a “limitless” ideal.

It is a commonplace to connect Lady Gaga to Madonna: they both have Italian roots, they both picked Italian-sounding names. But among many differences between the two, one might note the most fundamental one: they don’t belong to the same time period. Madonna, in the ’80s, was indeed friends with Andy Warhol, but her main acquaintances were fashion photographers such as, of course, Steven Klein. She didn’t say she was a “performance artist” — which would have been rather insane, since the relationship between her appearances on stage and Vito Acconci’s or Joan Jonas’s work was quite loose. Whereas, on the contrary, in the age of Marina Abramovic’s “pop performance art,” it doesn’t seem that strange for a pop star to claim a certain sense of familiarity. The name itself makes clear that times have changed: using “Madonna” as a stage name means that you relate to sanctity and religion — i.e., to the ancient world of Catholicism. Even if you want to shock the audience, it is still from the point of view of sacrality that the impact is intended. On the other hand, “Lady Gaga” is much more of a hybrid: Lady also relates to the Virgin Mary, hence, to the heritage of Madonna’s transgression, but Gaga is reminiscent of Queen’s song “Radio Ga Ga” (1984) — that is to say, it relates to pop culture itself. It mirrors its pop-cultural identity.

Lady Gaga’s attempt to be seen as, in a way, an actual contemporary artist could easily be mistaken for another token of what the French theoretician Guy Debord called the society of the spectacle: in such a social context, “pop performance art” would be just a new fashion for the spectacular to dominate human beings and to challenge their autonomy of mind. And of course, since, in the end, a musical performer expresses his or her talent in huge concerts, it also has a sense of “rowds and power,” as Elias Canetti would put it. All these people dancing together follow the lead of the singer, they follow Lady Gaga’s lead, in the exact contemporary equivalent of what Debord described in The Society of the Spectacle (1967). As he states it: “Where the real world is transformed into mere images, mere images become real beings — dynamic figments that provide the direct motivations for a hypnotic behavior.” Lady Gaga’s world is indeed made of images that are designed to strike the viewer and to shock him or her: the meat-dress she wore for the MTV Video Music Awards is a perfect example of that.

As such, there is a certain form of synesthesia in this pop performance art she suggests: the audience is at the same time a group of viewers, attending the spectacle, which is seen as the most fascinating reality. As she herself says to the crowd dancing at her concert, “You’re gonna remember that you are a goddamn superstar and that you were born this way.” By doing so, she produces a manifesto for a redeemed version of the society of the spectacle: indeed, it is no longer considered to be an instrument of oppression, a form of oppression in its own right. On the contrary, the oppression brings its own redemption: the spectacle has been transformed into a fairy, into a Monster Ball. It has been turned into its own Monster, into its own “phenomenon.” If Lady Gaga is “gaga,” it is over her own audience: she creates the illusion that these ordinary people who just come to see a pop star live, these crowds of workers, are her “baby monsters,” as if they emanated from her identity as the “mother monster.”

Of course it is an illusion, but this illusion exists during the performance: this little woman, nearly a girl — she is 24 — pretends to incarnate the anger, the energy, the magic of all these human beings. It is what pop stars are here for, obviously. But there is something different about Lady Gaga, an idea of sacrifice that could relate to Marina Abramovic’s famous piece Rhythm 0 (1970), in which she provided viewers with objects that they could use upon her body. As Gaga says herself: “My little monsters, I’m gonna be brave for you. I want you to forget your insecurities.” She sacrifices herself, not only for her audience as audience, but for the individuals that are part of it. Hence, she doesn’t really address them as a group, but as a gathering of identities. She is Lady Gaga and not Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta anymore, and that is because her self has disappeared into the persona she embodies on stage, the persona that is made up of the encounter between her and all the “weird people.” It is not meaningless that she wants to unite the feelings of all people that are generally seen as “outsiders,” gays and transsexuals in particular. Her features are not those of a person anymore; they are those of a symbol.

Lady Gaga collects all the identities of her spectators — she unites all of them, and her vision of pop performance art has a lot to do with the reinvention of the Ego. Indeed, her public figure is the result of the fusion of two very different conceptions: this symbolic perspective, that turns her into an expression of collective fulfillment; and another theoretical view, which is a renewal of the Platonistic concept of enthuziasmos. In a dialogue entitled Ion, the Greek philosopher Plato has Socrates explaining that a poet cannot be rewarded for his work, because, in the end, he is not the person in which the production originates: it is a god, a “theos” that comes inside of him and insufflates the piece of poetry he finally delivers to the world. As such, it appears very clearly that Lady Gaga is “enthusiastic” in Plato’s sense. And since we are in the age of pop performance art, and not of rock ‘n’ roll anymore, this revolution has an impact on her identity: “You can be whatever you want,” as she puts it. You can exist beyond the categories of beauty — a concept that is recurrent in the lyrics of her songs — or ugliness, beyond ideas of truth and falsehood. Among the inscriptions present on the stage of her show, one of them is particularly significant: “sexy/ugly.” Not “beautiful/ugly,” but another dichotomy, or perhaps, equivalence. One may ask: wouldn’t it be Lady Gaga’s final goal to make ugly things look sexy? And in that sense, she could accompany a fundamental shift in the morals of contemporary beauty, which is that ugly can be sexy, and sexy is perhaps the new beauty.

Knowing that, one is better prepared to understand the passion she shows for her attire, why she uses so many costumes on stage. Madonna has the same habit of changing looks, but not so often, not as much in one concert as Lady Gaga. By doing so, the new pop star attests that identity nowadays can only be conceived through multiplicity. She is a nun, a whore, a devil, an angel. She is a poor child threatened by a monster — she is a monster herself, as well. In this way, we perceive that her actual self is a fusion of all of these fictional personae. Pop performance art happens only during show time, during all the public appearances in which the pop-star-artist has made the world her stage. Aside from this public performance, we don’t know anything about Lady Gaga — nor do we want to. Like Andy Warhol, her personal life does not interest us. Or not really. Because what matters, more than anything else, is that during the time of the performance she creates a whole new world that is open to her “monsters.” That illusion is called art.