Harry Lime, the cynical and diabolical character played by Orson Welles in The Third Man (1949), would have never imagined that his legendary sentence was a prophecy. It became reality in Venice on June 4th, 2011, during the Golden Lion ceremony for the 54th edition of the Venice Biennale. From the top of the large Ferris wheel in the Prater amusement park in Vienna, Lime says to his moralist friend: “In Italy, for thirty years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, they had five hundred years of democracy and peace — and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.” In the end, the Golden Lion for best artist went to Christian Marclay, an American raised in Switzerland, for his work entitled The Clock. Marclay’s work of art is not a cuckoo clock, but rather a twenty-four-hour-long video consisting of fragments taken from several films, all having in common the presence of some kind of clock, whether a watch, a bedroom clock or a clock tower. One might say: “So?” Well, what makes this work of art a masterpiece deserving the most prestigious award of the Biennale is the fact that all the clocks in the video always show the viewer the actual time.

For instance, while I am writing this text in the last room of the Arsenale in Venice, there is a scene in which the clock says 5:39, the same as my mobile phone. In a minute there will be another scene with a clock showing 5:40, and so on. And therefore whoever purchases Marclay’s artwork will buy one and get one free: a contemporary artwork and a real clock that can be projected in the kitchen just to know the time.

The funny thing that everyone notices about this Biennale is the colonization of Switzerland, a pacifist country (according to Welles) but apparently capable — like humidity — of going everywhere. In fact, beside the winner of the Golden Lion, the artistic director Bice Curiger is also Swiss, as is Swatch, the main sponsor. The fact that Marclay won thanks to a clock makes for a hilarious confluence and seeming déjà vu. It is as if sometime in the ’80s the artistic director was Oliviero Toscani, the main sponsor was Benetton, and the winner was a citizen of Treviso with a work of art entitled Sweater.

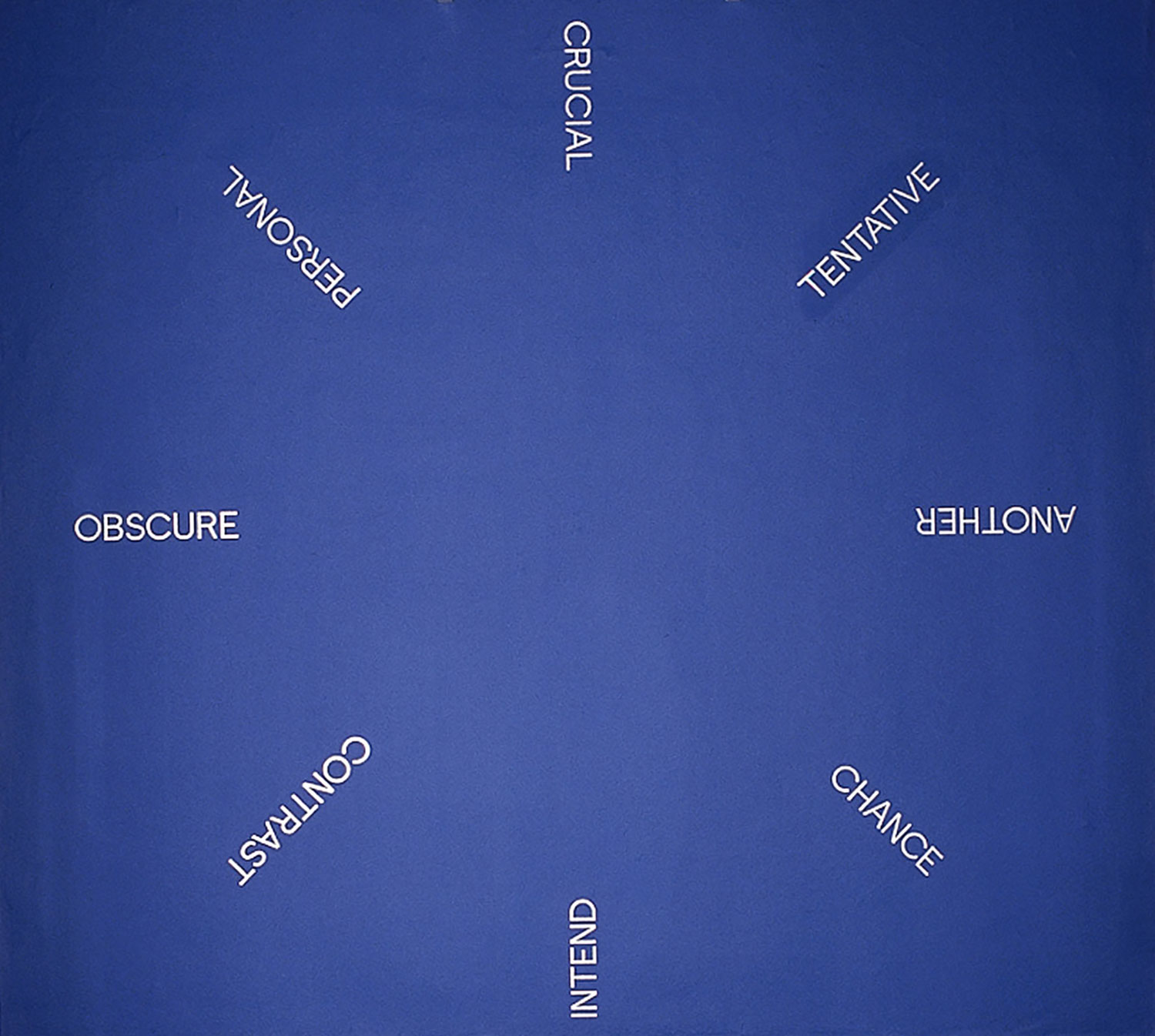

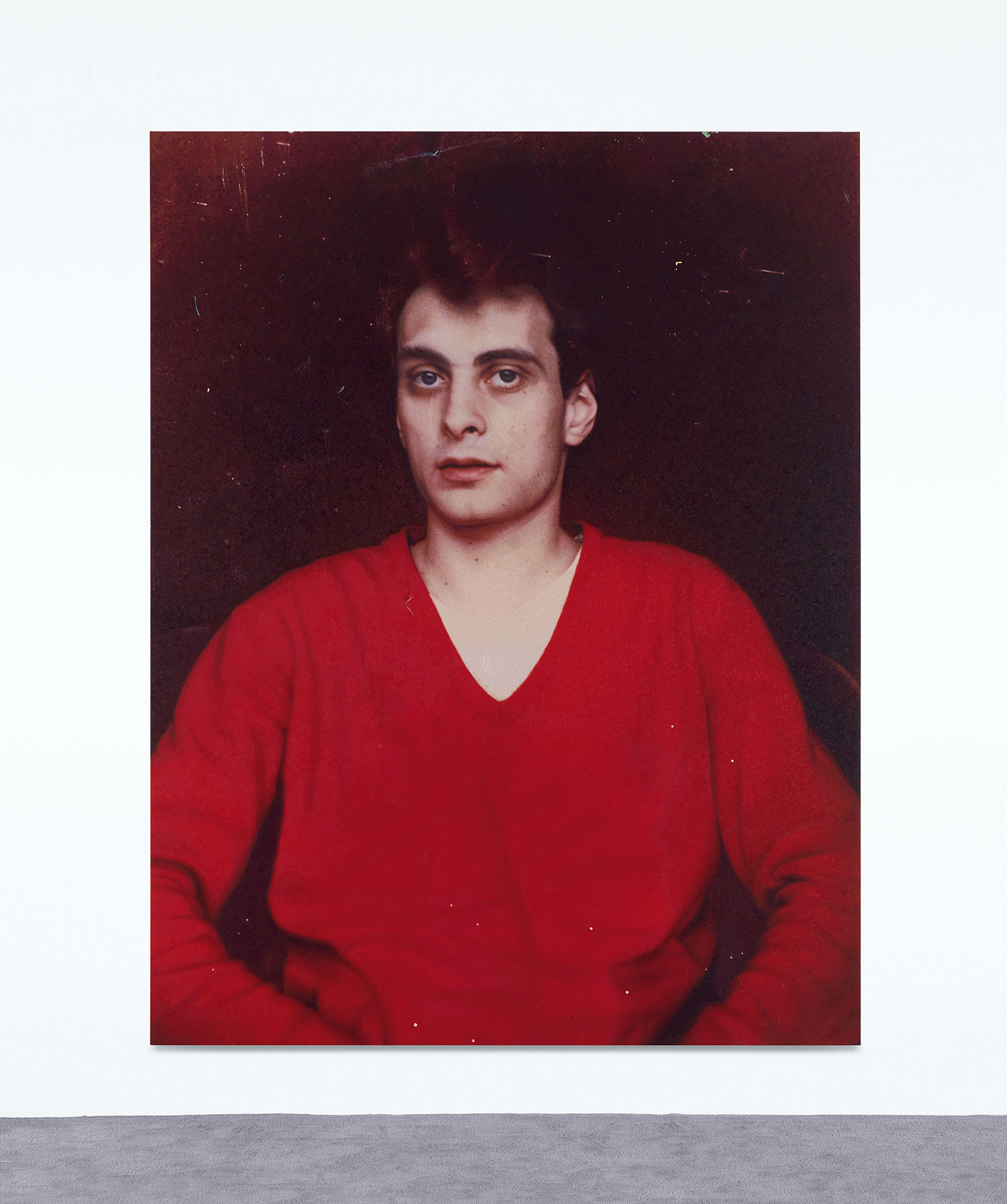

Also receiving an award for lifetime achievement was Franz West, the fragile guru and old-style artist who makes abstract and colorful sculptures exuding the desire to use art as a poetic game. The other Golden Lion for lifetime achievement went to eighty-something-year-old bad girl of contemporary art Elaine Sturtevant, aka STURTEVANT. A real character rediscovered only recently, this wild girl and feminist has spent her entire career making fun of and ripping off her male colleagues. While receiving the award she thanked those who have followed her career with trust and patience, including François Pinault, who anticipated the Biennale and devoted two rooms to her work at Punta della Dogana for the new installment of his collection.

However, the opening ceremony of the Biennale was just one of many — too many — events that have transformed this edition of Venice into the center, or perhaps epicenter, of a media earthquake, with celebrities competing against one other to put their names on shows, dinners, parties, awards, and to fly their flags on some palazzo in the lagoon: from Anish Kapoor’s magic (though slightly out of order) column of smoke at the Basilica of San Giorgio Maggiore, which required a horrible metal conduit that came out of one side of the Palladio-designed building, revealing the “magician’s trick” as if the paws of the rabbit were visible at the bottom of the hat; to the exemplary exhibition of the Prada Foundation at Ca’ Corner della Regina; to “Modernikon” featuring young Russian artists presented by Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo at the newly restored Casa dei Tre Oci at the Giudecca Island; to the dozens of national pavilions, which, not having a space in the Giardini, were scattered throughout the city — a fact that makes a visit to the Biennale feel similar to a treasure hunt.

In addition to the exhibition of Marisa Merz at Fondazione Querini Stampalia near Santa Maria Formosa, there was also a very delicate installation by English artist Ian Kiaer — a commentary on the restoration of the foundation’s building designed by Carlo Scarpa, who is the tutelary deity of Venetian modernist architecture.

Roberta Smith of The New York Times compared this swarm and accumulation, this tangled pile of exhibitions and events, to an enormous and untamable beast on which the viewer seems to have lost control. For Smith, the most hysterical, scandalous and embarrassing example is the perpetually stressful Italian Pavilion, a reminder of the sad state of Italy itself. Many visitors, most of them specialists who arrived in Venice for the four days of previews, began to ask if what was until a few years ago an exceptional richness of variety and dynamism has become a big pot in which everything is cooked together until it tastes the same — where everything looks so similar that it debilitates even the central event, the core, which is the Biennale.

On the streets, I often heard people complain of exhaustion, threatening a possible defection in the future. Certainly further reflection on the topic is required. During the opening days, Venice and the Biennale — which runs until September — are invaded by 13 million tourists; in just one day almost 17,000 people arrived on cruises. Only a small percentage of those will visit the Biennale and its many tentacles. In 1895, when the Biennale started out from Riccardo Selvatico’s conception, it was supposed to be a tool for revitalizing a decadent and moribund urban context. Selvatico correctly understood that the past could be kept alive only with a big dose of modernity. However, today the idea seems lost. A hundred and some years later, Venice is still a moribund city, if we consider its infrastructures and its daily life, although every two years the city gets this overdose of contemporary art that makes it lively again without making the situation vital enough to survive.

Maybe it is time to rethink the cure. Instead of a biennial electroshock treatment, it would be more effective to administer a daily or monthly dose of the contemporary art vitamin. The 54th Venice Biennale is a unique show that at the same time has shown itself to be at a saturation point. Before this saturation and related disaffection, already at a critical stage, undermines our remaining enthusiasm, it would be good to take a step back and try to imagine how to best go forward.