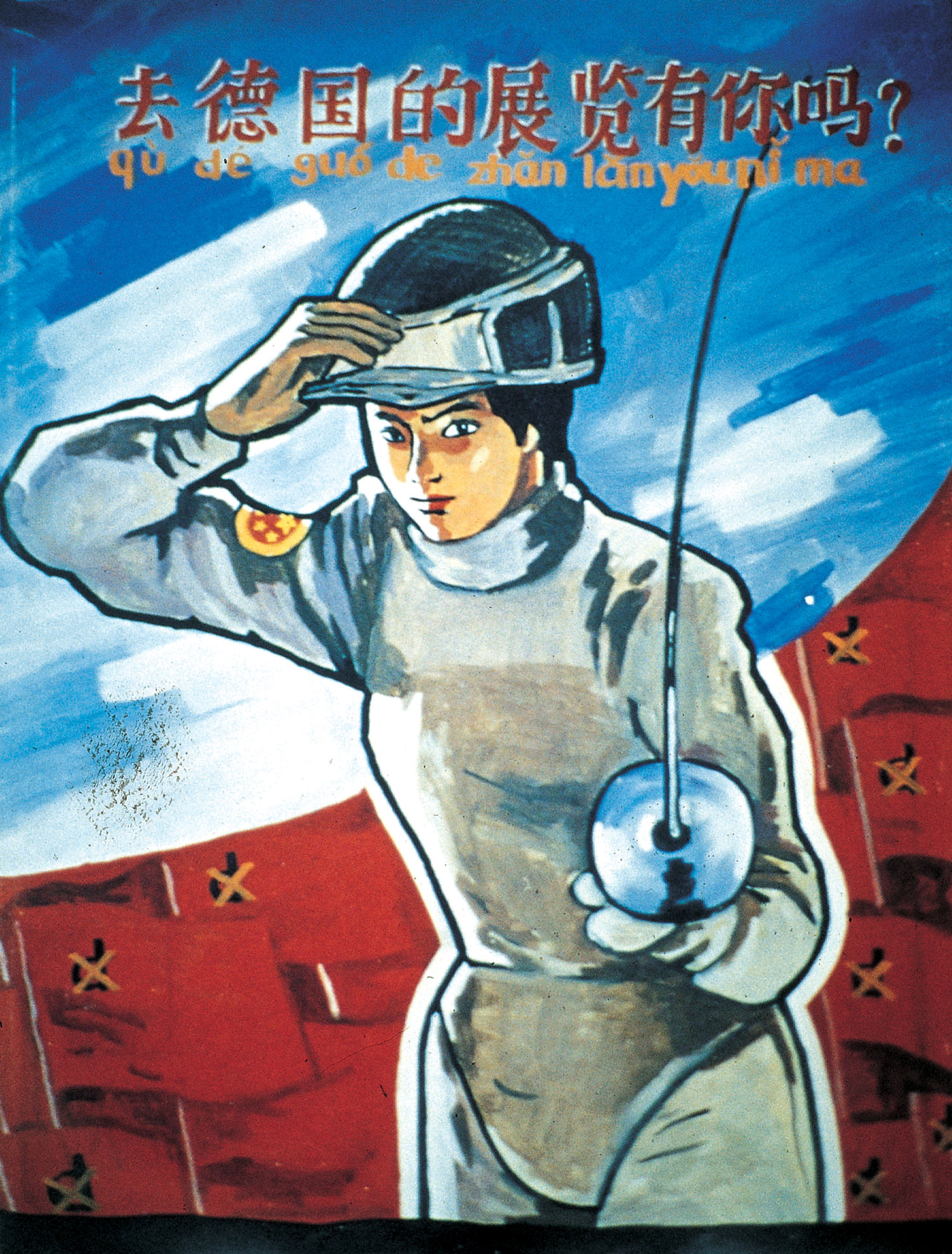

La Force de l’Art,” the first edition of a triennial initiated by the French Ministry of Culture, opened in the 7,000 square meters of the grand nave under the impressive, recently restored, vaulted-glass ceiling of the Grand Palais in Paris. With this impassioned and somewhat pompous title, the organizers, who delegated to fifteen curators the responsibility of realizing individually curated shows in this setting, were hoping not only to make up for the lack of such contemporary art events in Paris, but also to demonstrate the vitality of French art while trying to rally the interest of the general public, who, at the very least, would be interested in seeing the renovation of this illustrious Parisian edifice.

Whether its goal was met is difficult to ascertain, as the exhibitions were so closely related in terms of physical proximity, without being related at all. The diversity of the fifteen separate spaces seems to essentially be the consequence of a desire not to choose or sketch out any kind of general narrative, each curator simply writing their own story. Conclusion: “La Force de l’Art” reflects more than it foreshadows, highlighting a constellation of artists who have really counted in French art over the past fifteen years (Bertrand Lavier, Claude Lévêque, Alain Séchas, Bernard Frize, Jean-Luc Moulène, all of whom are represented several times throughout), in a kind of belated validation, which comes at the expense of younger artists, mostly absent from the show. This is revealing of two French qualities characteristic of the relationship between the art world and the State, which continue to condition the visibility of artists in France today.

Although clearly not facilitating the task of the organizers by its monumentality, the choice of the Grand Palais — site of the 1900s Universal Exhibition of which one of the pediments states its original function as a, “Monument consecrated by the Republic to the glory of French art” — testifies to the imbrication that the State fosters between the arts and patrimony. Rather than having new work produced, the majority of the works in the exhibition came from French public collections. That these collections, exceptional by virtue of their scope and quality, should be the object of such vast shows is the point: nevertheless, one can’t help but wonder why so few artists (i.e., Thomas Hirschhorn, Pascale Marthine Tayou, Véronique Boudier, Boris Achour or Yan Pei Ming with his redoubtable, still wet portrait of Dominique de Villepin) offered to show new work. Were they asked, them or their galleries, to take the opportunity? Or was there really so little time? To force could have been added a little velocity. In the words of Gianni Motti, who has tried in other instances to telepathically force a president of a republic to resign: “Nada por la fuerza, todo con la mente…” (Nothing by force, everything with the mind).