Maurizio Cattelan: Ciao, Kerstin. Sorry about that before, I didn’t hear you coming. I’ve always got these things in my ears.

Kerstin Brätsch: What are you listening to?

MC: My studio manager sent me the new Britney Spears, Femme Fatale. It’s great. All production, pure exterior.

KB: I’ll always remember her in 2007 at the MTV awards. She was barely there.

MC: I don’t know that. Maybe we can spend some time talking about celebrity. I’ve seen you in so many publicity photos recently. In magazines but also on the sides of buildings, on posters.

KB: Have you?

MC: And in other people’s publicity photos too.

KB: I don’t know about that. I am a woman, you know.

MC: Are you a narcissist?

KB: The myth of Narcissus has been inspiring artists for some time now. You see it in a lot of historical painting, from Caravaggio to Poussin to Dalí. Narcissus peers into the water looking for his true love, but finds only death. Today we look at the news for pictures of ourselves, but find only others.

MC: Is that a quote?

KB: Just because I pose for an image doesn’t mean that I’ll spend any time looking at it.

MC: I ask, you know, because sometimes a silly arts journalist will ask me something similar…

KB: About your works? The “Mini-Mes”?

MC: Maybe.

KB: Warhol once said that you should always have a product that’s not just you. Something that has nothing to do with who you are or what people think you are, so that you never start thinking the product is you, or your fame or your aura.

MC: I wonder what he meant. Do you paint by hand?

KB: Most of the time.

MC: Quaint. But isn’t Kerstin Brätsch anyway, all ways, only herself?

KB: Depends how you spell it.

MC: Your product and you, or that space between. Maybe you can help me figure this out. It’s tricky, and some people want to know.

KB: Your readers?

MC: Some writers.

KB: The designer Scott Morrison once told me that you never put your name on something you make. You can always come up with a better name. It also deflects some of that negative psychic energy that seems to accompany so much cultural reception these days.

MC: Energy?

KB: Much more interesting to talk about than inspiration, source, influence or even the drugs you’re on.

MC: But what about your name? Is the product you, in that sense?

KB: Perhaps this is more closely related to the signature, an old technology that seems to persist in spite of, or maybe because of, the general decline of handwriting — which is another great piece of technology, by the way.

MC: Do you sign your works?

KB: Never. But I’ve signed my friends’ works before. Debo Eilers and I made a show in New York last year, and I signed all these paintings he made.

MC: You work with a lot of people it seems. Adele Röder is another frequent collaborator. What is DAS INSTITUT, anyway?

KB: A beautiful friendship.

MC: You take pictures of each other, those I’ve seen.

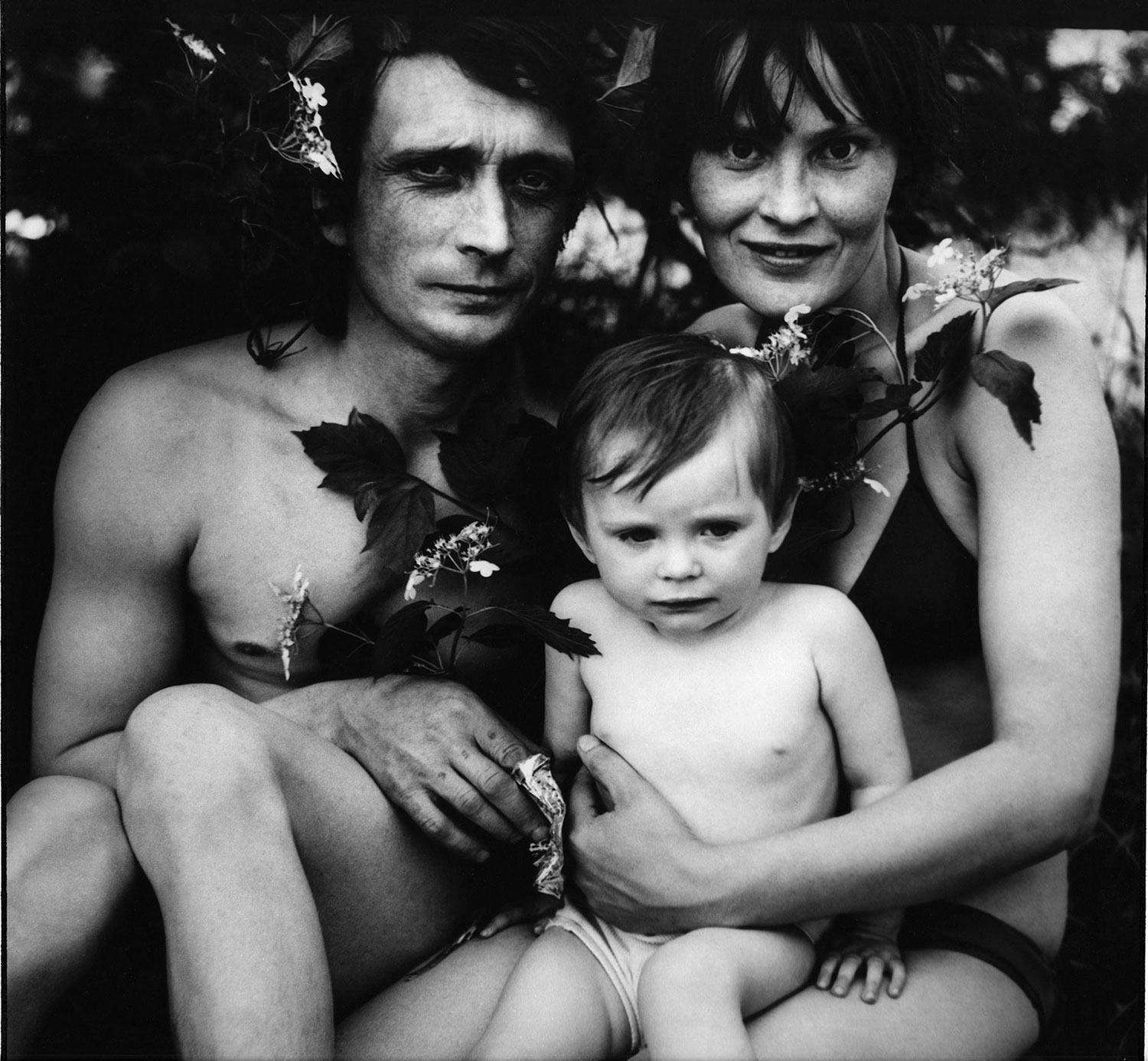

KB: Perhaps you saw them in some publicity photos. We did a series called “When You See Me Again It Won’t Be Me” (2008), where we just photograph each other very simply, against a black background. We paint ourselves black in part, altering our silhouettes and profiles. It’s an old cinema trick, before the green screen. Our bodies in that case are the templates from which we work. Actually, I guess that’s the case for other works too. Anyway, those pictures, like all of my pictures, have different uses. They are collected in a 35mm slideshow projection called Viola! (2007- ongoing). Others end up on posters or in other people’s projects — I gave one recently to a friend for his album cover. Sometimes they are also in magazines, like a lot of other art works. But for us when those photos are in the magazines, they are not documentation or excerpts of a work but rather an instance of it.

MC: But then your name, in signatures or titles or whatever, is that a brand?

KB: It’s an abstraction. If I wanted to use the trendy theoretical language of the moment, I might say that it’s a kind of lossy compression, since once performed that source material can never really be restored to its original state. And if I did restore it, its fidelity wouldn’t quite stand up to the original. This is all to say I can’t really be my name anymore. But what’s a name anyway? Someone once described this situation to me as a trap. Which makes me think: maybe it would have been better to pick another name, when I was first starting to show my work.

MC: What kind of name?

KB: Something easier to spell. I remember getting a phone call when one of the biggest tabloids in Germany ran a poorly researched knockoff of an American newspaper’s article about me. My name was in this big bold headline there. I had no idea about this until my parents saw it and called me. The text made some ridiculous claims and made me a kind of painting star or anti-star — it was hard to tell which. The scandal was the artist, not the works. But that’s what this game wants: all of you.

MC: What do you mean?

KB: This system that directs the traffic of art. Everything changed a lot with the introduction of wider markets, elaborated professional training and greater stakes in the realm of presence and celebrity. We know that. But the price for all this is your social energy, your friends, your leisure time, your image and your past, the fabric of your life — it all becomes in a sense some kind of exploded biological script, a living text. Rather than being absorbed into your work, it’s absorbed into something much more abstract, along with your work. You’ll see shows with titles like: “Names Not Works.”

MC: So what can you do?

KB: I hope the work speaks for itself in that regard. What do you think about scandal?

MC: A good living.

KB: Didn’t Richard Prince say that once?

MC: I think he said that about art.

KB: Do you have any more questions?

MC: What about social networking?

KB: I’m not on Facebook. Some of my friends are. I was thinking about that the other day. Like, most people today use Google and Facebook. They use both of these things. And both companies are making a lot of money. But their approach to the world is different at a foundational level. Google is rational and scientific. They hire the best engineers in the world, pay them the most competitive salaries, and engineer the shit out of the world’s problems. Facebook’s approach on the other hand is to…

MC: Engineering makes me think about well-made objects manufactured by experts.

KB: Do you think that’s out of date in our field?

MC: I’m not sure. Tell me about your ghosts.

KB: The ghosts are paintings on mylar, which is an industrial plastic film. They’re oil paintings, done by hand, and many of the motifs are inspired by digital effects and digital brushwork, if you will. You can hang ghosts however you like, both sides are fine for display. On one you’ll see through the plastic, so the paint will have a flattened, produced appearance. The opposite side reveals the brushwork, the production.

MC: They’re transparent. It’s hard to isolate them from their environment.

KB: The ghosts are mostly copied from original paintings that are oil paintings but are not ghosts.

MC: Those are not transparent then?

KB: No, they’re on paper.

MC: The one you showed me is large, the paper curling at the corners.

KB: That’s from the studio, the abuses of the studio.

MC: So they are similar, ghosts and the non-ghosts. Why repeat yourself?

KB: There are many answers. How to choose one?

MC: Give me a moral answer.

KB: Truly democratic learning happens by way of repetition. Access to the richest fountains of knowledge or the best learning technologies can never compete with the radical potential of repetition and cognitive agency. Have you read The Ignorant Schoolmaster?

MC: No. You’re also interested in fashion.

KB: Fashion fades, only style remains.

MC: That’s Coco Chanel.

KB: Maybe not the first to push that one along.

MC: Tell me about the parasite patches you and Adele made?

KB: They are big, square knitted pieces — and they’re intended to live on the backs of other pieces of clothing. You can pin it to your Uniqlo sweater and have a Uniqlo parasite patch, or maybe your Jil Sander jacket and have a Jil Sander parasite patch.

MC: Punks do that on their leather jackets.

KB: Do they?

MC: Yes, I’ve seen it in Rome.

KB: Well, the parasite patches are fashion pieces but not quite, since they require a host to be used properly. They’re not fully functional on their own.

MC: They’re not paintings?

KB: I’m interested in painting that’s a bit more animated than something you’d just hang on the wall. A character or an experience is interesting.

MC: You’re getting very conceptual here.

KB: No, it’s all quite simple and real. It’s the real world.

MC: So we’re talking about technology, fashion and painting. What’s going on here, how are these things related in your work?

KB: My friend Bosko Blagojevic once said that all technology is destined to become fashion. And the model or primal scene for this kind of movement is the wristwatch. It starts on your wrist.

MC: I’ve heard of that guy.

KB: Things in motion seem a little more interesting to me than things that are growing.

MC: What’s the difference?

KB: Endless growth, without restraint or respite, cancer, finance capitalism…

MC: Listen, I have to go soon. Maybe we can have lunch together next time.

KB: What about tomorrow, back to Milano?

MC: Tuesday. Tomorrow I go to the Met to study the masters.

KB: Don’t forget a pair of binoculars for the passing present!