Originally published in Flash Art no. 277 March-April 2011

Keith Sonnier is one of the first artists who worked with light as a sculptural material. In the late ’60s, he started experimenting with a combinations of incandescent light fixtures, neon tubes and other materials to explore the diffusion of light through various materials and the surrounding architectural space. His work encompasses a large range of media, including performance and film, and is material and process based. For Sonnier, a sculpture is more than merely an object on a pedestal; rather, he deals with the “sculptural conditions of space.” In the following text, I will discuss Keith Sonnier’s work and artistic development in relation to space. The text is based on the artist’s remarks during a symposium at the New Museum in New York and an interview with me as part of the project “Personal Structures: Time Space Existence.”

For Sonnier, the concept of space has been an important motive since the beginning of his career. There are two possibilities: “One can think of space as a microcosm or a macrocosm… in the sense that it is either small and you look into it, or it is big and it encompasses you.” Sonnier says that he has always approached his work with a somewhat ‘situational’ condition in mind. It is this situational condition that seems to lie at the basis of his thoughts about space: “One moves into the work; one moves out of the work; one moves past the work.”

In Sonnier’s sculptures, the viewer is a pedestrian: he moves through the space and senses the light. It is this combination that is important to the artist. Light can be perceived as a volume that one could physically move through. In what he calls his ‘floor-to-wall works’ — in which the floor and wall become the sculptural support — “one can move into the pictorial space, and in doing so, one becomes aware of the parameters of the space.” Sonnier’s sculptural objects can transmit or project light. He stresses the psychological aspects of the light in the viewer’s encounter. Whether it is clear and direct or not, according to the artist the light has an affect: “Light on the surface of the body affects the mind.”

INBETWEEN SPACE

Sonnier divides different periods of his work with regard to how he thought about space and how he used it. He states that his first objects were based on the five senses: “on how something felt, or looked, even on how something smelled.” While making these works, he noticed that there were different associations coming up. “In the end, the most intriguing thing about the sculptures was that they became about the space in between, and what actually happened when you physically got inside the piece and how the body actually felt being there.” Addressing this in-between space was the start of Sonnier’s idea of the viewer as a pedestrian: he focused on how someone would move within the space that was created by the artwork.

By leaning the work on the wall and by using the architectural support of the wall, the viewer could physically move into it. The floor-to-wall relationships within and the architectural confines of each particular space became important to the design of the work. In this sense the work was led by the space it would eventually occupy. In defining these given spaces, the relationship of the floor to the wall replaced the traditional sculptural base, or plinth, as a support. The base of the sculpture had been left behind; influenced by Carl Andre, Robert Smithson and Constantin Brancusi, the support in Sonnier’s sculptures became integral.

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL AFFECT OF LIGHT

From the late ’60s, Sonnier began to introduce light into the idea of the ‘space-in-between.’ He remarks that, so far, his pieces were mainly based on touch, or different kinds of tangible principles. The use of light and color seems to have allowed the artist to focus more on other senses as well. “Somehow the light, the reflection, the physical being of the person in the sculpture — and the fact that one could physically move through the art — became increasingly important to me. I began to embrace light […] in a very intense way.” These first works were made with incandescent light, which is an electric light. The effect of color was intensified after the artist started using neon, a gas-generated light.

It was especially the psychological affect of color and how it altered a space that was of importance to Sonnier. The artist describes his experience of the work In Between (1969): “I stood in front of the piece and watched the lights on either side of the sculpture blink on and off, and somehow this seemed important in the creation of a sense of another spatial dimension. It was this weird kind of psychological thing where I could sense that I could somehow go into the wall.” He adds that the work introduced transparency by actually allowing you to see through space.

DEEP SPACE

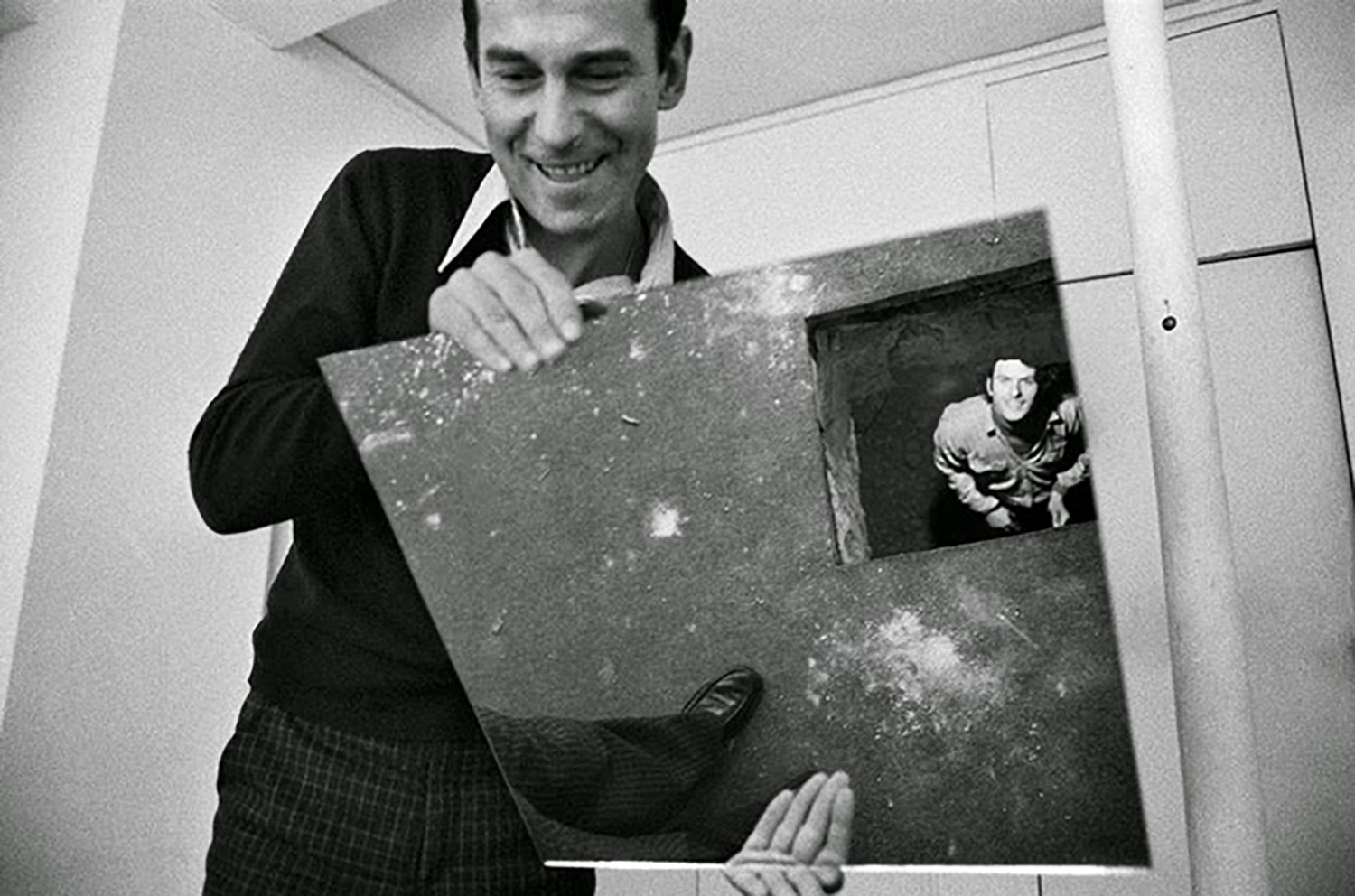

Sonnier began to make video works on the basis of his installations and began to question what was beyond the concept of the enclosed space. Mirror Act (1969) is an example: it was installed in the artist’s studio and made from two parallel mirrors on opposing walls. The two mirrors facing each other began to create a different, ‘channeled’ kind of space. The artist remarks that it was a much more complex kind of space for him to work within and refers to it as an ‘infinity channel.’ “Before, I could stand in front of the work and somehow attempt to move into it, but now with these mirror pieces, I could literally be in the sculpture and see both my front and my back. It was this front and back sort of working idea that began to alter my thinking about using light and working within architectural space. When I stood in the sculpture and the mirrors allowed me to open up the frame, so to speak, I could begin to set up a different kind of dimension. […] I could see the front and the back, the top and the bottom of the space. I could move into space in its entirety. I could literally go into it and feel all its dimensions.” It was this situation that allowed Sonnier to think about what he calls ‘deep space.’

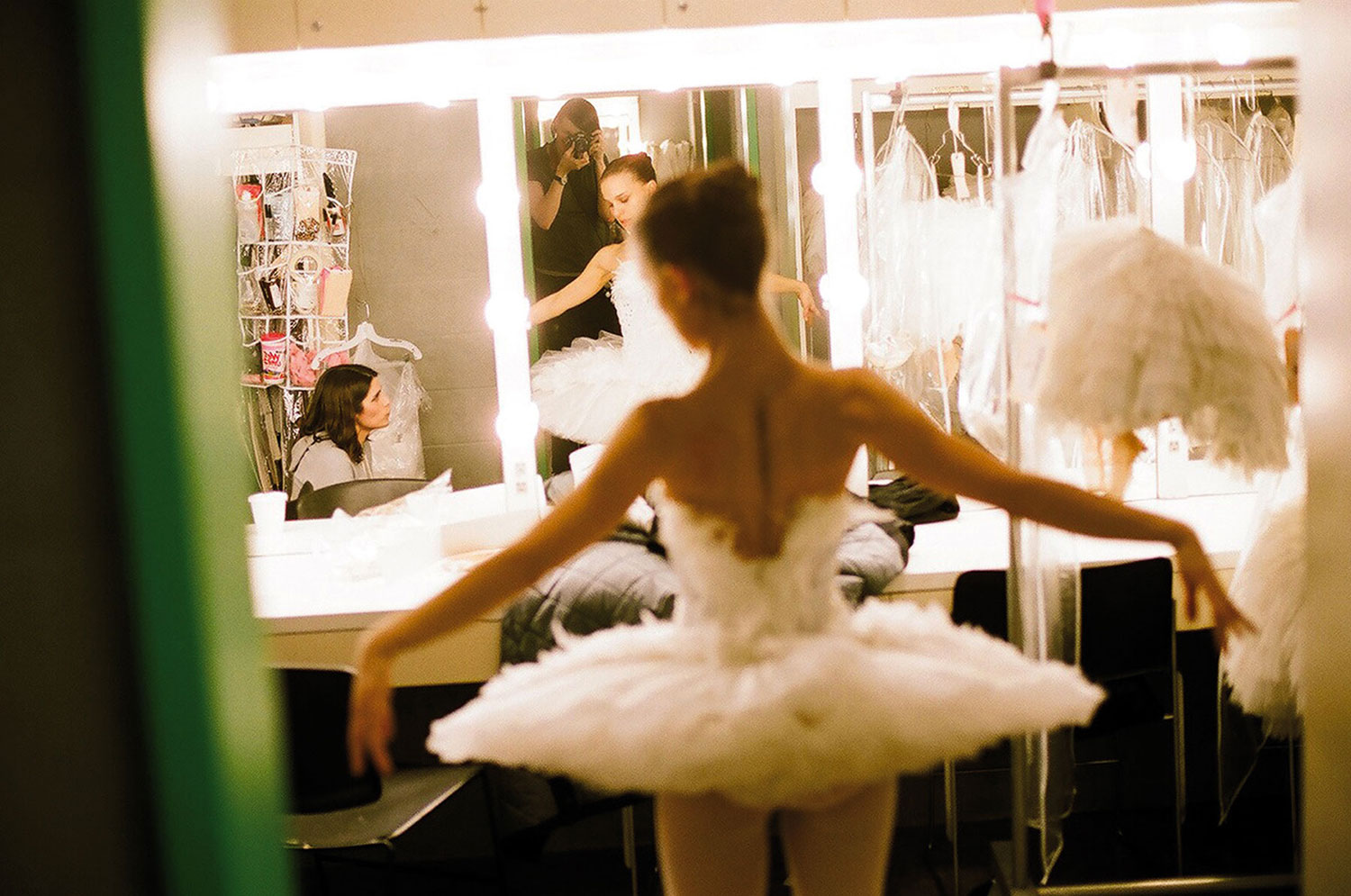

Not only the aspect of the infinite channel and being able to see all sides of the space were important. Sonnier adds that he thought about this space in terms of being literally immersed in the space. He gives another example: Fluorescent Room (1970), which he made in Eindhoven, The Netherlands. “It was completely lit with fluorescent powder. It was like a wild abstract disco. The piece was extremely successful, and being inside it felt like being in a kind of lunar landscape; it felt like you were moving in deep space in a controlled abstract environment.” The work is related to some of the early works in which he felt he could enter the space, being able to ‘move’ through the mirrored glass. Sonnier says that its realization led to a renewed embrace of the architectural element and to a new understanding of what contemporary architecture is about.

THE TRANSMISSION BETWEEN SPACES

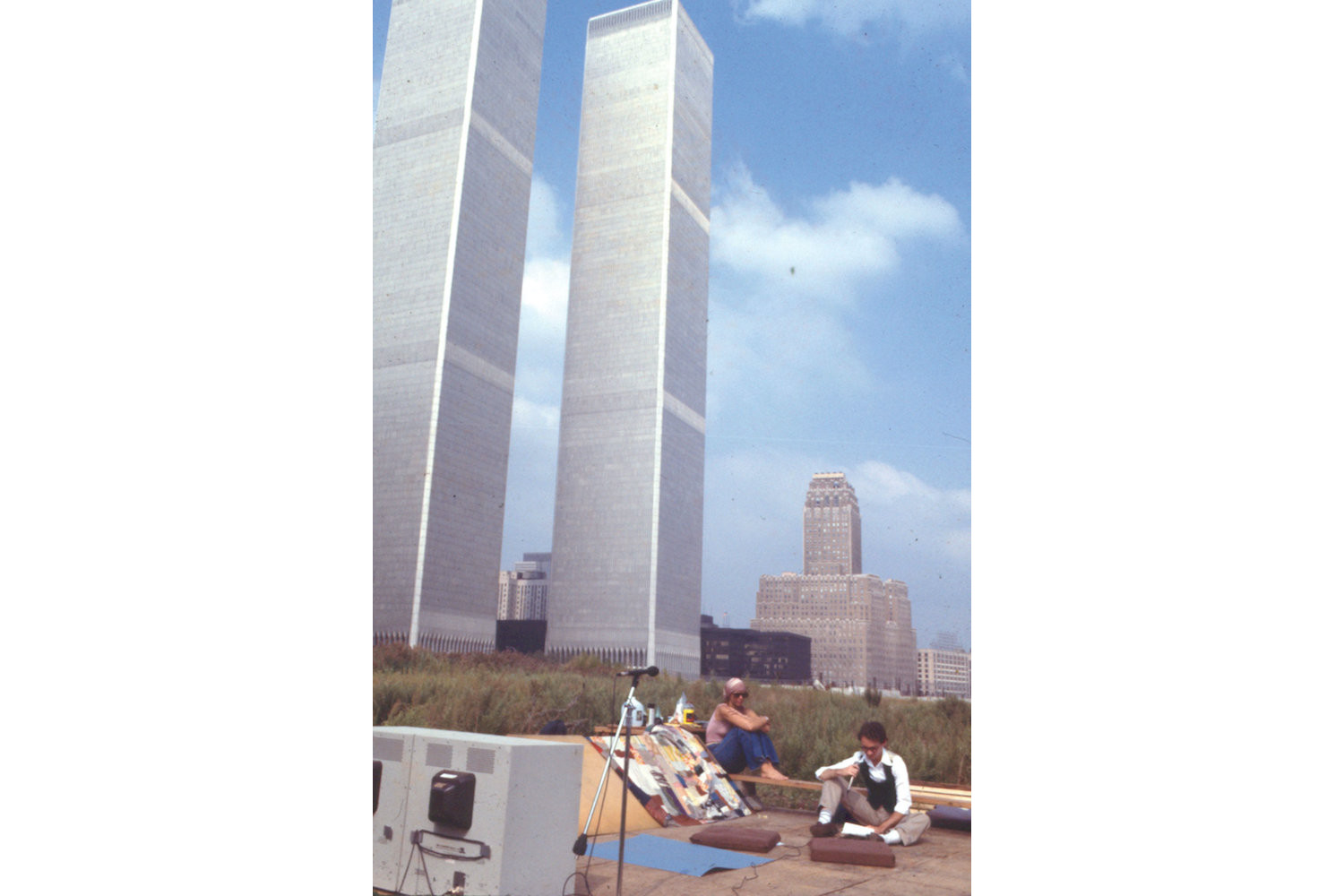

It seems to have been this research into the concept of deep space that resulted in experiments with radio waves, sound waves and different types of radio signals. “I did interactive sound pieces, where one space was connected and amplified and bugged to another space, which in turn was amplified and bugged back across the country.” The works revolved around the possibility of a person to physically be in Los Angeles, while his voice would be in New York. The artist adds: “You could feel these people were enclosed in a confined space, but there was also this sense of the sound traveling through the expansive space between.” After these works with the transmission of sound, Sonnier made a similar transmission happen visually, for example with Liza Bear in Send/Receive Satellite Network (1977).

NATURAL SPACE

Influenced by the situation in the art world in the ’80s, Sonnier left his experiments with sound and returned to his early work. “The art world reverted back to normal, with paintings and lots of bronze sculptures. I had to reinvent myself once again, because I realized that if I were to continue to make art and have some sort of interest in space, I would have to try and work in other directions.”

The environmental use of space became important to him again. A series of inflatable pieces, which he did early on in his career, began to re-enter the work. “I got interested in atomic bombs and what happens to a space when a bomb goes off: the impact, the explosion and the implosion.” But soon after he started working with the idea of architectural space and how the viewer as pedestrian might negotiate and move through the space to experience the art. He created several works for airports, and it was around this time that the artist began to think about color as being able to create a volume. Sonnier still continues his experiments with space. Nowadays, his work revolves around a natural type of space. “I am trying to deal with space in its most primitive sense.” A new series of light installations called “Oldowan Series” was on view at Mary Boone in New York in January 2010. Referring to the finds of the earliest manufactured stone tools at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, the individual works in the series are named after the designations of Paleolithic riverbed sites. In reference to his own artistic research, Sonnier remarks: “Artists are supposed to delve within many different levels of the culture. The job of the artist is to acculturate society. We need art in order to live.”