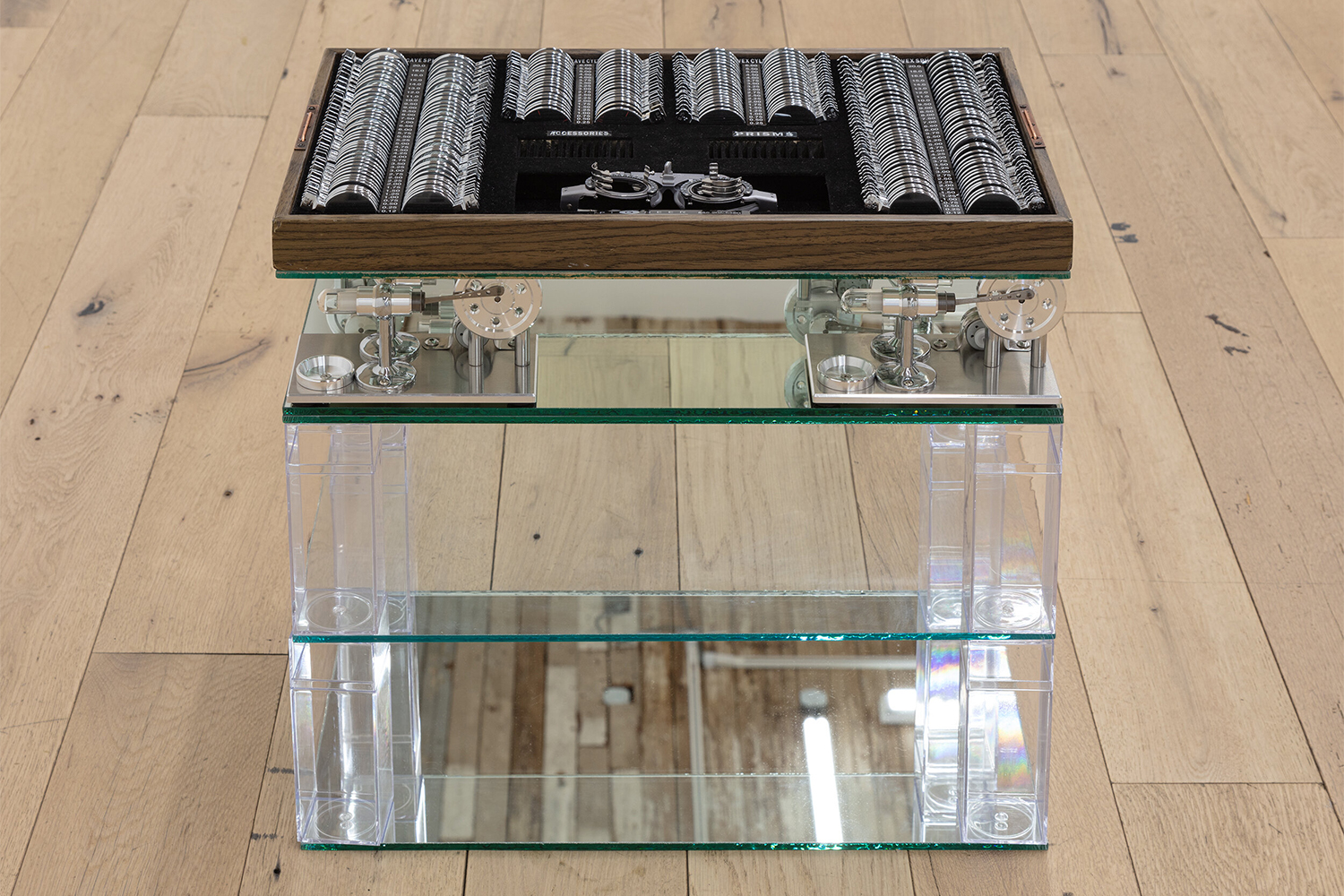

As part of his recent show at Sweetwater in Berlin, Kayode Ojo presented an ascending row of letterboxes, each opened to display an array of mirrored panels and the internal rigging of a Kiev 88 camera. While the work’s title, I put all of my energy into this tower (2021), suggests a level of overwrought tinkering, even expressive bombast, the quintuplet of boxes that compose the sculpture is stringently demure. Its geometric construction and serial arrangement obscure the artist’s energetic transmission; or, put differently, the energy in question seems to have been directed toward self-effacement. Rather than “cool” restraint, however, the gulf between the work’s locutionary address — i.e., the claims made for its sprightly animation — and the benumbed forms on view in the gallery ultimately suggested an arch sarcasm. Indeed, as Chloe Stead notes in a review of the show, the title is in fact a quotation from Ben Wheatley’s 2015 film High-Rise1. With this work it seems we are even farther from Ojo than we thought, its titular declaration revealed to be merely prosthetic. A similar tendency toward bait and switch is evident across much of Ojo’s recent production. This work, mostly photography and sculpture, takes its cue from commercial presentation schemes like the storefront and vitrine, ushering in a dynamic of desire and deceit native to the sale. This is also clear in I put all of my energy into this tower, whose disassembled camera tucked into individual showcases frames the gallery as an untypically refined and shiny chop shop. The artist consistently returns to these sorts of eclectic materials. Re-functionalizing music stands, bar carts, chairs, and other design objects as bespoke pedestals for an array of (seemingly) luxury items, Ojo choreographs a series of sly subversions by harnessing the rhetoric of display. As much as these works communicate anything about themselves, then, they also act as projection screens for viewers’ interest in particular items, ideologies, and ways of looking.

Ojo has a keen eye for sumptuous austerity. One need only consider the AMAC boxes — part of MoMA’s design collection — that act as supports in Flyover State (2021) and let him speak (2020) for examples of the artist’s incorporation of reduction into a Lucullan lexicon. In these works and others, he tends towards T. J. Clark’s thesis that “negation is stylish.”2 Nevertheless, Ojo’s reductive impulse steers clear of minimalist orthodoxy. While Donald Judd disavowed his works’ affinity with “Good Design,” emphasizing instead their autotelic lack of external mediation, Ojo’s seductive sculpture falls outside this hermetic materialism.3 Chandeliers, sequined blazers, fringe dresses, champagne glasses, and guns are but some of the goods arrayed across Ojo’s idiosyncratic supports, whose glinting surfaces frame the work as equal parts precious and provocative. The French call “window shopping” lèche-vitrine, framing the commodity- fetish as an urge to lick (the translation of lécher), consume, and satisfy objects on sale. It is this sort of desiring relation that is simulated by Ojo’s sculpture.

Rather than minimalism, then, Ojo veers toward work made in the 1980s by the likes Haim Steinbach, whose shelf-sculptures also simulate an experience of shopping, topped as they are by organized rows of commercially available objects. As described in a 1986 panel at Pat Hearn Gallery, Steinbach and his peers (Ashley Bickerton, Sherrie Levine, Peter Halley, Jeff Koons, and Philip Taaffe joined him in conversation) were no longer convinced by work that broke down “the process of the corruption of truth.”4 Rather, as Bickerton explains, his peers were interested in modeling their psychic attachments to this corruption, particularly that of commodification, using it as a “platform or launching pad for poetic discourse in itself.”5 These artists, like Ojo, seek out a transitive handling of the commodity-form that attracts and refracts back to the viewer their investment in its production. Taking a term from Mark Fisher’s writing, we might say they operate under the assumption that contemporary subjects undergo a “precorporation” into capitalism, that collusion is both inevitable and a jumping off point for analysis.6 Rather than repeat a (by now) well- rehearsed reflection on the reified status of the artwork, however, Ojo harnesses the commercial frame as an analytical structure to seek out other elements that traffic through the art world and suffer a similar fate, pointing out the public’s participation in this process along the way.

Ojo consistently returns to a type of figuration rendered in absentia. Without trousers (Suitmeister) (2021), for instance, features a folded sheet-music stand operating as the skeletal substructure for a glittering set of accoutrements: carabiner hooks slung low toward the ground, StarSide Crystal teardrops, and a silver sequin blazer, its left sleeve pointing diagonally upward in a limp simulation of disco gyration. Here we have an example of what Robert Slifkin calls “abstract animism,” one pushed to the near edge of representation.7 Apart from the anthropomorphic outline of his works’ assembled components, Ojo’s sculpture indexes — or purports to index — a more potent form of figural residue. For, after collecting the clothing for his sculpture, most of it bought online from fast-fashion retailers like Zara or ASOS, Ojo usually tries them on. In turn, the works’ latent sense of presence is not only secured through their suggestive postures but also the artist’s performative pretext in which he temporarily occupies the objects on view. Similar to the winking title I put all of my energy into this tower, however, one shouldn’t consider Ojo’s imprint on the work as an uncomplicated transmission of his body into the aesthetic field. Rather, he encodes another type of misdirection.

As Isabelle Graw has written, “artworks circulate on the market

as names.”8 The minute, arguably nonexistent trace that Ojo leaves in his work puts into relief and embarrasses this hunger for artists’ bodies and biographies. In fact, these traces are ultimately hagiographic. Whatever body appears here is the by-product of speculation. Is this

mere guesswork, however, or, as Graw suggests, a more nefarious, near- financial form of conjecture in which locating the absent artist promises pecuniary advantage? Ojo’s work suggests the latter by setting up a viewing situation in which corporeal voids are anxiously filled in the by the audience. Whether these spectral forms are imagined as Ojo or someone else, the contemporary demand for figuration is foregrounded either way, framed by the artist as an exercise in consumption. His sculptures also hint at the manner in which identity positions are especially subject

to this process. Many of his sculptures, like Overdressed (Blush) (2018), feature swishy postures and flamboyant materials that might easily be read as “queer.” Furthermore, in I don’t want either of us to regret this (2021) shown at Sweetwater, the artist included a Sony television monitor playing looped footage from Call Me By Your Name, providing the work a rather unambiguous gay reference point. These examples feature a series of signaling mechanisms that coalesce into identitarian décor. In turn, rather than confirm some sort of ontological essence embodied by his work — which merely waits for the logician properly attuned to its coded iconography — Ojo reveals the dialogical construction and desirous fantasy that always define these sorts of assignations.

Ojo is not the only subject up for grabs in his work. Or, rather, he understands the contingencies that construct the subject include its various companions. Since David Joselit’s 2009 essay “Painting Beside Itself,” the “networked” art object has become increasingly fashionable in critical parlance.9 Taking Martin Kippenberger as an historical crux, Joselit offers a genealogy of painters that follow in his footsteps, making work that engages the expansive field of discursive and material flows in which it would ultimately circulate. One obvious aspect of the network that goes unacknowledged in his text, however, is networking, that perversion of the social field into a competitive marketplace. After parties for museum and gallery openings are one such space in which social and professional spheres converge, where the establishment of an artist’s profile becomes intimately tied to where and with whom they find themselves. At a two- person show with Zoe Leonard at Paula Cooper Gallery in 2018, Ojo displayed a series of photographs taken at various after parties, their location and the opening in question listed in the title for each. Most of these are portraits, like Afterparty for “Janiva Ellis: Lick Shot” at 47 Canal, Mika Japanese Cuisine and Bar, New York, NY (2017), and display fellow partygoers in the midst of dancing or primping, capturing the various performances through which attendees establish themselves in relation to a complex mix of (para)social factors. Unlike Wolfgang Tillmans’s images of party spaces the morning after, Ojo took these images in the midst of celebration, showcasing the ephemeral gestures, looks, and posturing that contribute to the fabrication of public persona.

Afterparty for Robert Bittenbender and Maggie Lee “Flowers in the Attic” at Bed Stuy Love Affair, The Cardinal, New York, NY, Valentine’s Day, 2015, Uniqlo (White) (2019) reconfigures the after party into a sculptural format, its expository title time stamping the sculpture and tagging Ojo’s interlocutors. A pair of distressed and dirtied white jeans suspend from yet another sheet-music stand just above a mirrored platform, their wear and tear appearing like battle scars from a night on the town. The artist’s physical registration on the object, more explicit here than in previous examples, along with the jeans’ melodramatic presentation, imbue them with a mysterious, almost libidinal pull similar to that of the relic. The artist, the opening, and the party afterward go through a process of cathexis, coming out the other end in Ojo’s sculpture as constituent features of his self-reflexive play with the commodity fetish. In this way, Ojo also grapples with the expansive site of art’s production and the spaces in which it accrues value, contextualizing “the apparatus through which the artist is threaded” as a multitudinous array of elements that includes bars, parties, milieux, and other aspects of the social field.10 If he isn’t the first to consider these ostensibly peripheral sites as coextensive with the museum or gallery, outlining the contours of the art “institution” is nevertheless an important and increasingly occasional analytical premise. Again, the critical or at least parodic accent of Ojo’s work depends upon the desiring relation established between the viewer and the work, framed as it is through the language of commercial presentation (one might reasonably bring up Tobias Spichtig’s recent series of disembodied mannequins for Balenciaga as an example of such sculptures’ use within actual stores).

Perusing the various examples described here, it becomes clear how Ojo’s work offers a way out of the division between figurative and abstract practice, between visibility and consistently invoked terms like opacity or refusal. Ojo locates a third option, one that aims to understand how representation, bodies, and subjectivity function within the aesthetic-commercial frame of the art world, one that derives value from funneling artists through a veritable regime of identification and disclosure. The artist’s choice of materials is especially important here. The barrage of reflective surfaces and mirrors that define his work multiplies the sculptures on view as both object and image, always already transformed into spectacle. Additionally, if Ojo convincingly arranges his sculptures to offer an air of grandeur, the materials themselves are knock-offs, one short-circuited representational scheme among many others. In no way do the concerns outlined here exhaust the intrigue of Ojo’s work; however, his sculptures’ self-reflexive bent to the conditions undergirding art’s valuation is, I think, an essential feature of the work’s emphasis on display. Rather than didactic indictments, therefore, Ojo’s critical accent emerges through his deft ability to model, anticipating our attractions toward particular interpretive frameworks and key words — biography, body, identity, expression — and reflecting them back to us as fetishistic attachments and false starts. These are desire machines, their product corroding the art world’s set of self-assured heuristics that transform artists, artwork, and affects into ideological pawns and conceptual punch lines.