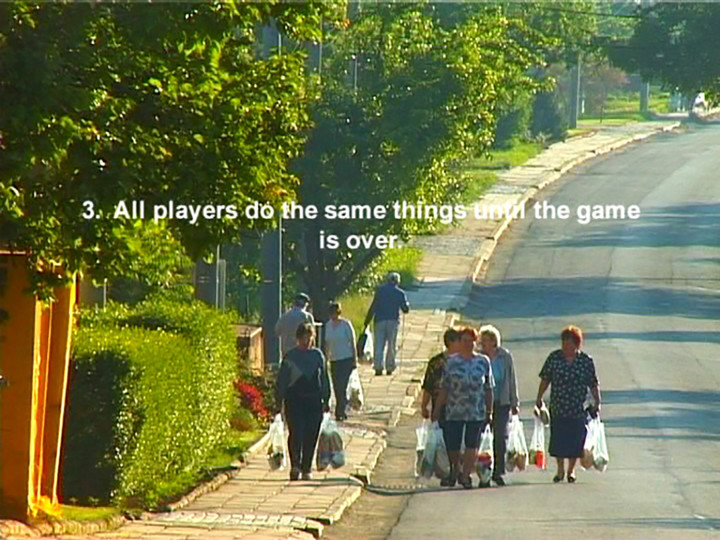

Kateřina Šedá’s work in the rural atmosphere of Central and Eastern Europe is usually interpreted as social intervention. However, when Kateřina Šedá synchronized the activities of nearly all three hundred inhabitants of the small southern Moravian community of Ponětovice for one day, she was not trying to get them to reflect on themselves or change their behavior, but rather to showcase ‘nothing.’ Perhaps this is best expressed in the title the artist chose for the project, There’s Nothing There (2003), a phrase used by the people who live in the environs of Ponětovice to describe ordinary life there. When, for the duration of one day, all the village’s inhabitants did what they usually did — with the sole difference that they did it together — the everyday was transformed, paradoxically, into a festival. Kateřina Šedá developed her particular relation- ship to the regime of visibility in her projects It Doesn’t Matter (2005) and What Is It For? (2006) that she worked on together with her grandmother, Jana Sedá. The aim of the first was to eradicate the phrase “It doesn’t matter,” a phrase used by her grandmother in response to all efforts on the part of the family to awaken her from her lethargy. Her interest was piqued only by remembrances of the years between 1950-1983 when she was in charge of inventory at a large department store that carried a wide variety of goods. Thus Kateřina Šedá tried to induce her grandmother to recon- struct the world of her active life by drawing the goods she would order for her stock room. The resulting series of drawings by Jana Sedá are thus a singular archive of intimate memories that nonetheless take on the stark form of an inventory catalogue. The effort to attain the most complete listing possible contrasts sharply with the frag- mentary quality of the items, which are, unlike tools, merely spare parts, lacking independent functionality. Each object before us appears quite mechanical, with no context whatsoever, as when we recall memories out of chronological order from different periods of our life.

Equally mechanical are Jana Sedá’s answers to the questionnaires prepared for her by her granddaughter, in which she was supposed to react spontaneously to what different things were good for. Listed in alphabetical order are the names of things and activities to which Jana Sedá was then to associate a corresponding function. Considering her advancing illness, it must be noted that a significance-laden and frequent reaction regarding the functions of things or activities was “for living.” Jana Sedá not only responded that way to temporal and vital concepts, but also to place names. Paradoxically, places that were geographi- cally or politically closest to Jana Sedá did not fit the pattern. Although she lived her entire life in the environs of Brno, she did not refer to that city as “for living,” but “for making tractors”; similarly, “Russia” was “for everything.” On the other hand, “grandmother” was “for nothing.” For Jana Sedá and for us as well, life was elsewhere.