I Am My Body

A thump, thump, thump opens the 1980 movie Right Out of History: The Making of Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party. Filmmaker Johanna Demetrakas chronicles Chicago’s rope jumping, a part of her exercise ritual at the time. At seventy-nine, Chicago still exercises regularly. During my visits to her home and studio, I noticed she usually stops at 4:00 or 5:00 p.m. to enter her room-sized gym. In a watercolor from her 2005 book Kitty City, she depicts herself bent in half, legs over torso, while managing to pet her cat, Romeo (5 PM: Going to the Gym, 2001). She says, emphatically, “I am my body.”²

Judy Chicago’s “Body” of Work”

A number of Chicago’s works focus on women’s bodies and bodily functions, always from a feminist perspective. For Chicago, feminism means the right to full expression of the self. In 1972, she added Menstruation Bathroom to the collaborative multiroom installation Womanhouse. At a time when television censored the word “pregnancy,” Chicago publicly claimed a basic, messy function of the female body. In her 1975 autobiography, Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist, Chicago referred to the paint on her canvases as her skin, indicating a merger of intellectual and bodily expression. During the 1970s, Chicago produced the “Smoke” series, which often featured the female body as a Paleolithic goddess among plumes of colored smoke, a symbol of bodily sanctification and the dissemination of femaleness into the atmosphere. In The Dinner Party (1974–1979), Chicago represented historical female figures by the culturally damned parts of their bodies, their genitalia, to express her outrage that women across time and space suffered from Western culture’s essentialization and suppression of the individual character and achievement of each. Glass pieces, produced primarily since 2000, feature hands and heads, male and female, sometimes showing skeletal structure and musculature to emphasize “humanness” no matter the external categories. In 2013, Chicago produced a lithograph of her own nude body. Titled Aging Woman/Artist/Jew, the piece boldly, but not without anxiety, attested Chicago’s place in the world at age 74. In the Birth Project, completed in 1985, Chicago explored meanings of the birthing female body.

Stratified Aspects of the Birth Project

The Birth Project showcases multiple needlework methods. The art world, at the time, categorized the Birth Project as traditional women’s craft. Chicago contended that emphasis on message defined the work as art; emphasis on skill defined the work as craft. In the Birth Project, Chicago transformed the status of textile and needle media.

Chicago worked with about 150 women needleworkers, scattered geographically, providing underpaintings, cartoons, mock-ups, color specifications, and written directions for the transformation of her images. Between 1980 and 1985, eighty-four exhibition units were finished, each inclusive of a textile, with documentation to tell the story of its completion and give credit to the needleworker(s). These units were shown singly or in small groups in conventional and unconventional locations like libraries and hospitals. Chicago made the work easy and inexpensive to ship, hang, and see, a means to expose images of birth to a wide, decentralized audience. Eventually, the works were gifted to over sixty collections — museums, galleries, and a number of non-art institutions. In the Denver area, Planned Parenthood of the Rocky Mountains displays Birth Trinity Quilt Batik (1983), and the Hartford Seminary in Connecticut displays Guided by the Goddess (1983). The totality of the Birth Project was never shown at one time in one place. In 1985 Chicago published a Birth Project book, no longer in print, which made her overall concept clear and unified the story of the process and much of the imagery, demonstrating relationships among the eighty-four exhibition units. The book details the roller-coaster emotions of Chicago and the needleworkers, often through the words of the needleworkers. The sentiment was summarized by Frannie Yablonsky: “We are creating within Judy’s creation.”³ The stratified aspects of the Birth Project — the exploration of a subject rarely seen in Western art, the birthing woman; the nonpatriarchal, metaphorical exploration of women’s bodies by women; the decentralized collaborative process; the metamorphosis of women’s craft into art; the redefinition of art and craft; and the means of broadening the audience — can be mined for meanings. Judy Chicago, Elizabeth Blackwell place setting from “The Dinner Party,” 1979. Embroidery on linen and china paint on porcelain. Courtesy of the artist and Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Collection of the Brooklyn Museum, New York.

Timely Now

Current societal/artistic interest makes the Birth Project timely. In the United States, reproductive rights are under threat of termination legislatively and through court action. The 2016 presidential election revealed acceptance of demeaning attitudes toward women and their bodies after a candidate bragged about his proclivity for illegal sexual groping of women and yet was elected.

Psychological Shift: Self-Knowledge, Power, and Determination

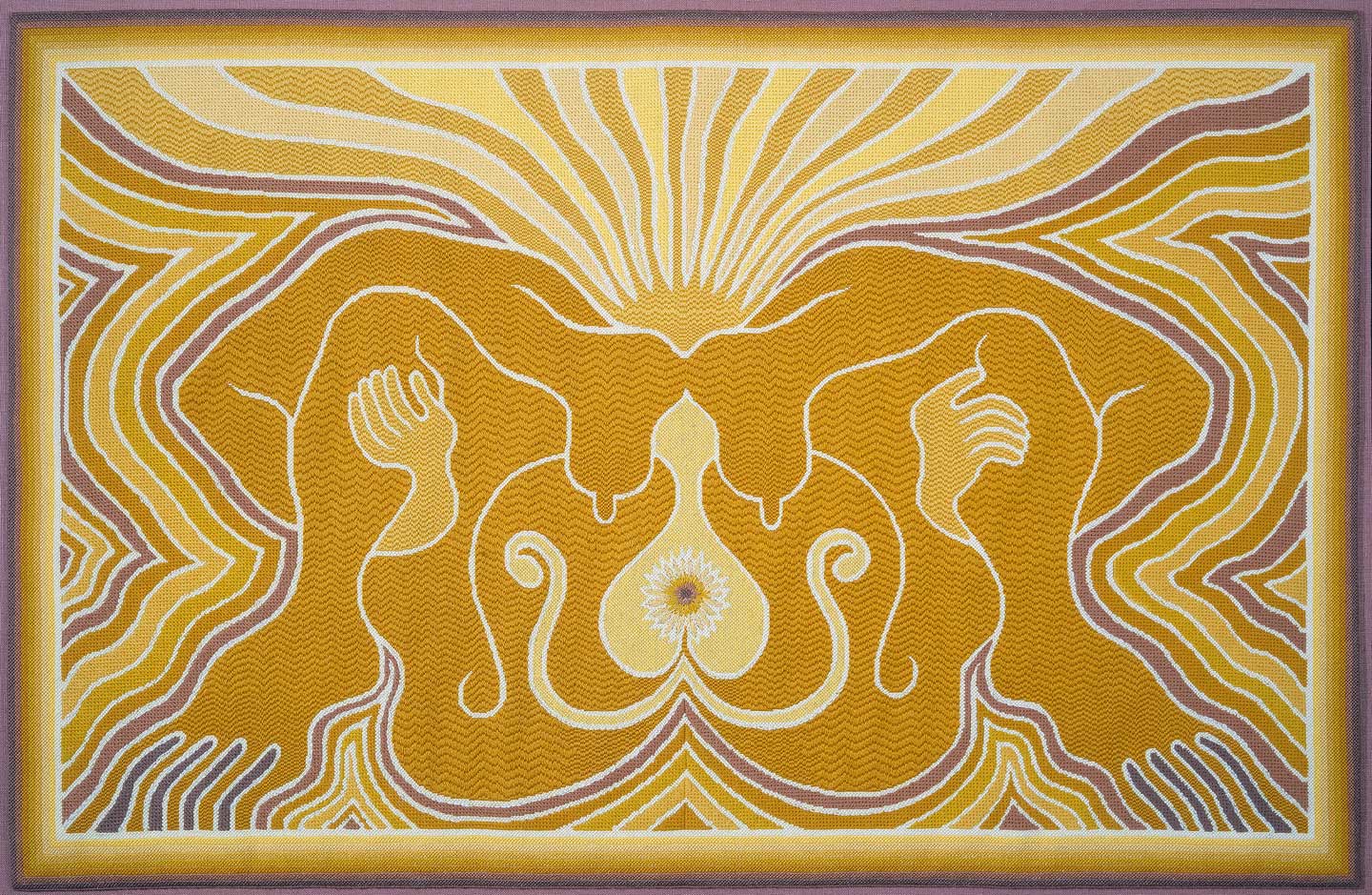

Chicago’s images demonstrate a psychological shift within women in Western culture. They afford a vision seldom seen since the Neolithic, when woman embodied creation. Chicago’s images, however, transcend visual resurrection. Together they extol women’s will to self-power on an expansive scale, their will to create and self-create, and their ability to celebrate themselves for that creation. In the Birth Project women birth themselves; they birth the universe and its contents; they birth and care for children. Chicago’s images expose the physical and real but also reveal birth as spiritual and intellectual, a source of myth and symbol.

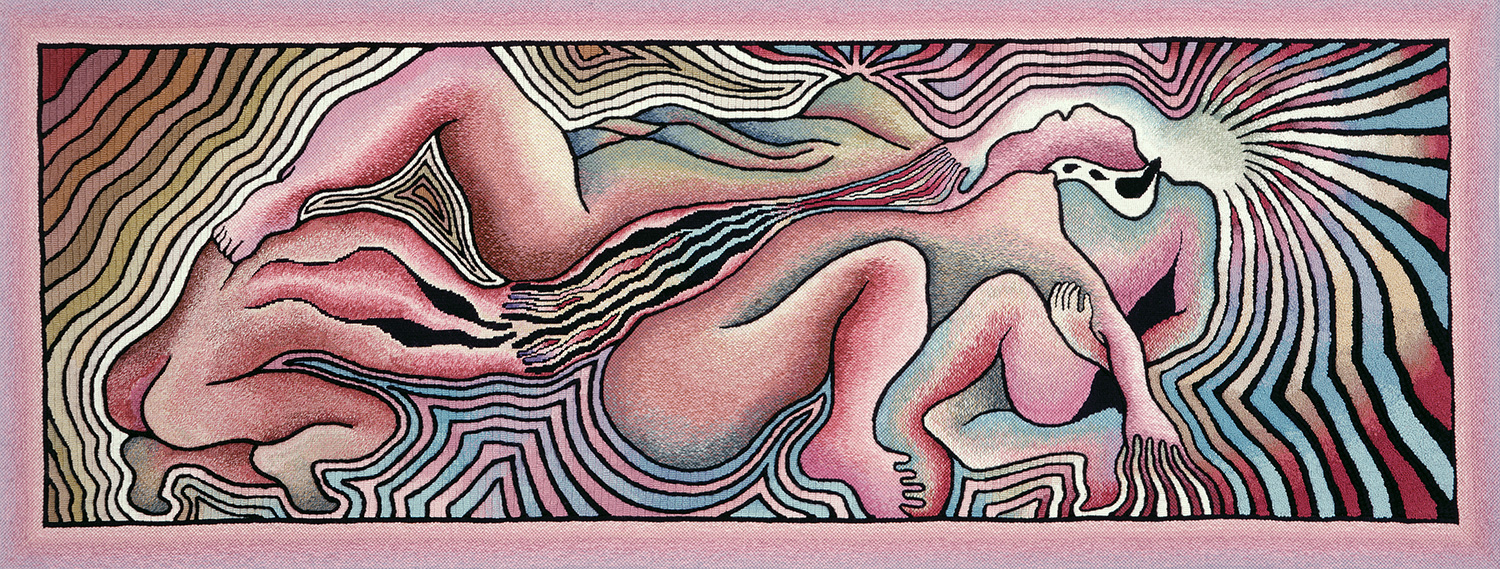

In “The Crowning” series women look downward to view their own processes, to know, to declare self-authority. In The Crowning Needlepoint 3 (1983), the body forms a lepidopteran silhouette, a symbol of bodily and psychological transformation, a reference to the birthing/creation at hand but also to this realization of knowledge and self-determination. This woman confidently holds her own legs apart while bands of yellow and gold stream from her head like thoughts to span the space of the composition. Energy reverberates from her body and the act she oversees. The crowning, the moment the baby’s head appears, symbolizes the climactic realization in all creative endeavors — the birth of a human, the construction of a building, a painting, a dinner, a business, a scientific research project. The holiness of the woman, inclusive of her knowledge, creative act, and body, is emphasized by the central altarpiece-like composition as well as by the stitched patterns of light-giving color and sparkling threads.

Childbirth in America

Chicago, with collaborators, developed three exhibition units in 1982–83 titled Childbirth in America, to be mounted at hospitals, libraries, and conferences. Each included a textile with extensive documentation to trace the historical migration from woman-centered birth events, often attended by midwives, to events controlled by medical men who increasingly, often unnecessarily, intervened with tools. Once anesthetics were introduced to alleviate pain, women overwhelmingly accepted the medical model. In first-wave feminism, this relief became a political goal for women. Then, in the 1940s and ’50s, “natural childbirth” and the Lamaze method were introduced by male practitioners. Pain was to be managed and utilized as a natural barometer of the process. A scan of articles from the last decade on natural childbirth/midwifery versus the medical model shows Chicago’s presentation may be more salient currently. Interest in women-centered births has grown alongside a rise in the number of childbirth rights organizations, yet many feel the medical model predominates with an increase in interventions but without greater assurances for birthing women. Some feminists, on the other hand, criticize the righteous stance of the natural childbirth movement and rejoin their first-wave sisters in accepting medical interventions, particularly to negate pain.

Birth Trinity, Needlepoint 1 (1983) relates to Childbirth in America. Birth Trinity demonstrates an alternative to the traditional “lying on the back” position, used pervasively by the medical profession in the United States until change began to be demanded in the later decades of the twentieth century. Historically, other cultures favored positions like squatting, kneeling, kneeling on all fours, sitting upright, or standing. Women also lay on their sides or often took a sitting or semi-sitting posture in which another supported the woman from behind while a midwife kneeled in front to administer to the woman laboring and to the child emerging from the womb. These positions encouraged greater pelvic space, less pain, and fewer interventions. The sitting or semi-sitting posture is used by Chicago in her Birth Trinity image. She includes the birthing woman, a supporting figure behind her, and a midwife.

Ambivalency in Motherhood

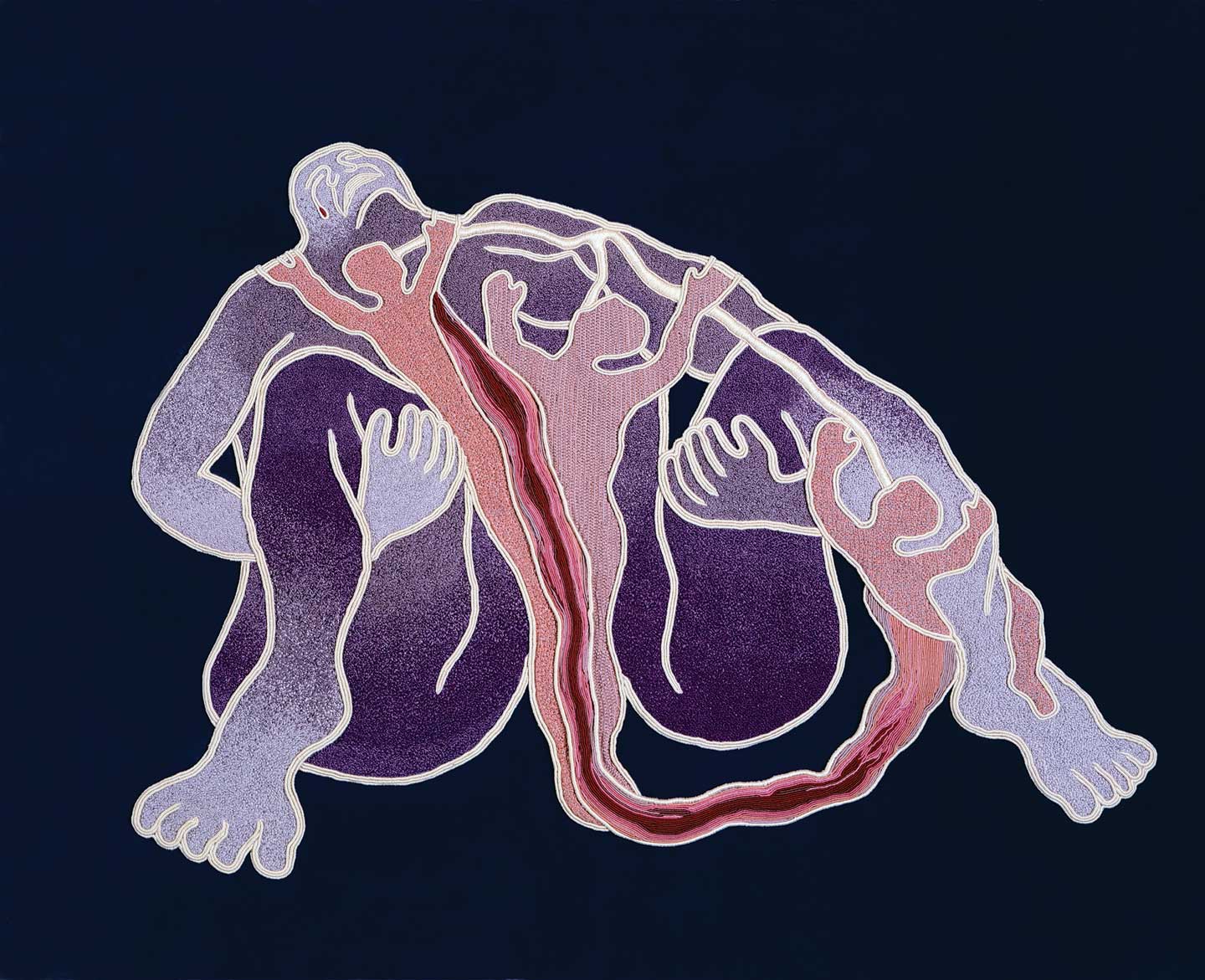

Historically, images of mothers, particularly mothers and children, propagandistically molded women into culturally acceptable roles. Chicago defied the norm by including images of maternal ambivalence. Chicago gave respectful, even heroic, voice to feelings not customarily allowed to women in a patriarchal society. In Smocked Figure (1984), a woman covers her face with her hands, distressed at the prospect of her pregnancy. The needleworker for this piece, Mary Ewanoski, recalled finding her own mother crying when she knew she was pregnant with a fifth child. In Birth Tear/Tear (1985), a woman strains to birth and nurture her children who cling to and grab for her. The “double tear” of the title refers to the 50/50 possibility of perineal tears during childbirth, but also refers to the weeping of the figure in response to her struggle with motherhood.

In several exhibitions mounted during the early 2000s, a complex view of motherhood also emerged. Myrel Chernick, an artist and curator, based the exhibitions “Maternal Metaphors” (2004) and “Maternal Metaphors II” (2006) upon her own experience. In her essay published in 2012, “Reflections on Art, Motherhood, and Maternal Ambivalence,”⁴ she recounts grappling with pressure and chaos, with finding time for herself and her work. Still she drew inspiration from mothering. She felt anger and guilt but did not doubt her decision to have children. She felt most mothers endure powerful dual feelings. Chicago’s own visual exploration of maternal cognitive dissonance within the Birth Project precedes these exhibitions by nearly twenty years.

The Narrative Continues

A number of collections, curators, scholars, and artists continue the narrative begun decades ago by Chicago. Among them is the collection at the Department of Midwifery, King’s College, London, which pioneers an effort to gather artwork devoted to birth and its processes. Titled the Birth Rites Collection, it includes several Birth Project works. In addition to Myrel Chernick’s curatorial work, mentioned above, in 2010 Jennifer Wroblewski curated “Mother/mother-*.” In 2012, Rachel Epp Buller published Reconciling Art and Mothering, essays by artists and art historians, with a jacket featuring a 2005 graphite Self-Portrait by Diana Quinby that showed her massive prenatal body as viewed from below. Chicago’s 1982 quip is still apropos: “If men had babies, there would be thousands of images of the crowning.”