Early on a recent spring morning, I tucked my trouser legs into my socks, hopped on my bicycle, and started a slow climb up Swains Lane, a narrow and vertiginously steep road in north London that runs from Hampstead Heath up to Highgate Village. It is tree-lined and meandering, looking more like a country lane than a road in Zone 2.

The sun was low-angled and dramatic, illuminating tarmac that was still slick with rain from showers the night before. As I made my ascent, I passed a cyclist lying on the ground surrounded by a small group of people, his face covered in blood.

About halfway up this perilously steep hill is 81 Swains Lane, which sits on a small plateau before the terrain continues to climb again toward Highgate. British architect John Winter designed and built the house for his family, and he completed it in 1969. It is a striking but simple steel-framed building: a three-story rectangular box with its facade taken up with large glazing units and Cor-Ten steel cladding, a rust-red metal that oxidizes over time to develop a dark patina that protects from atmospheric corrosion. The project was one of the first steel-framed houses in the United Kingdom and the first to use Cor-Ten in a domestic context. It subsequently became one of the few modern houses to be granted a Grade-II* listing.

The house borders Highgate Cemetery, one of eight large graveyards built around London in the early nineteenth century. Winter built his house on the garden of the old superintendent’s cottage, which shares a boundary wall with the cemetery’s western wing and a chapel that also once housed a mortuary.

The architect kept the external face of the building as flat as possible to avoid overhangs that would cause issues with uneven weathering of the steel. The building’s large double-glazed units are set flush into the steel frame with ventilation provided through sliding doors on the ground floor and a series of story-height pivoting steel-faced flaps on the upper two levels which are interspersed with the glazing.

Inside the building, the steel beams remain visible, allowing a clearly legible grid plan with modules of eight feet by twelve feet by twenty feet. The steel frame is clad externally with welded Cor-Ten that forms a continuous cover and is set two inches from the frame with the gap filled with insulation material in a valiant but ultimately ineffective attempt to reduce cold bridges.

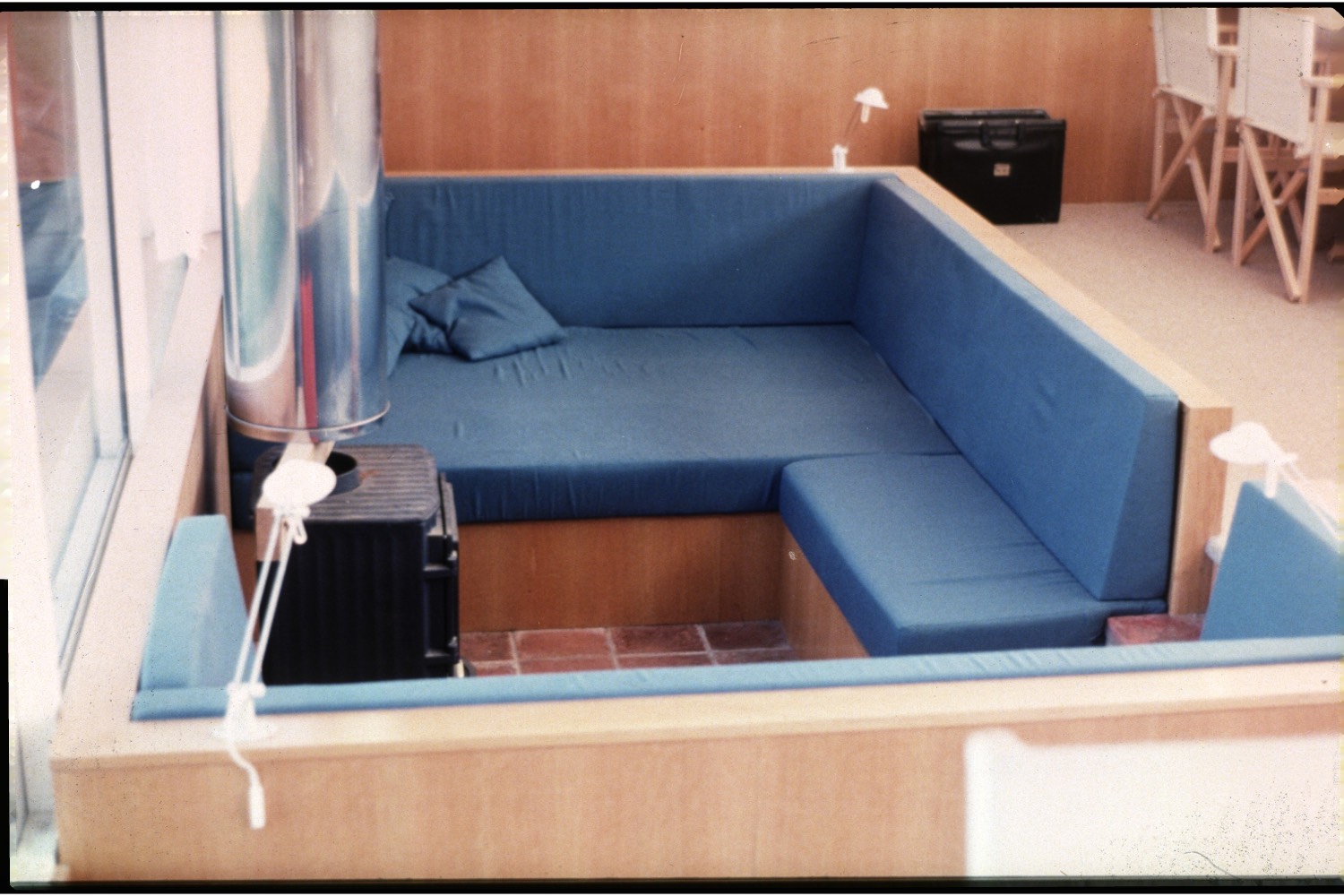

Winter developed an unusual program for the house, with the kitchen and dining room located on the ground floor, lined with industrial quarry tiles, four bedrooms and a bathroom housed on the first floor, and the study and living room located at the very top of the house arranged around a central fireplace and stairwell. This made the room impractical for hosting or getting furniture into, but gave it a sense of quietude and of sitting up in the tree canopy. “Quiet living on top. Sleeping in the middle. Noisy at the bottom,” as Winter described it.

It was the second house that Winter had designed and self-built for his family, the first being located on Regal Lane in Primrose Hill, overlooking London Zoo. Both houses were heavily influenced by his time spent living and practicing in San Francisco in the 1950s, where he worked for SOM and the Eames office and developed an interest in simple steel-frame building methods and a culture of self-built projects, both of which he took back with him to London.

A study on the building published in Architect’s Journal, in 1970, notes with interest that the Winter family already had “experience of living in a modern house.” The tone sounds like they are about to take part in a radical social experiment or embark on deep-space time travel. It highlights how forward-thinking the design was at the time, with its minimal yet inventive use of industrial materials and an internal flexibility intended to shift and adapt as the life of the family developed.

I grew up not far from the house and went to school just down the hill from it. It has been a consistent backdrop to a good few decades of trips up and down the lane for the miscellaneous purposes that make up the tapestry of life: going to the dentist, visiting friends, attending piano lessons, crashing terrible house parties, playing tennis with my grandmother as a child, and later taking her on long walks after she developed Alzheimer’s. I no longer live in the area, but my family do and my most recent visit to the hill was just before midnight on Christmas Eve as my brother and I cycled up the silent and dark street looking for a pub that was rumored to still be open somewhere on the other side of its crest. For many of these years I was unaware of 81 Swains Lane, or had little interest in it, or both, but at some point that I can’t quite remember I started cycling up the hill just for the sake of looking at the building.

In 2013, the house went up for sale following Winter’s death a year earlier. From the outside little seemed to have changed. Going through my iPhone and selecting the location in my camera roll I found the last image I took of the house, which was in late 2021. The exterior garden walls were covered with overgrown vines and a geodesic domed greenhouse was visible through the cast-iron fence. Through the heavily glazed facade it was possible to glimpse, in that way that will never cease to be fascinating, the details of another person’s life.

Between then and now the building was resold once more and now sits unoccupied as it awaits renovation. In its present condition it is striking how run down it looks. The windows are dirty and streaked. The upper floor has been entirely stripped. A child has covered the windows with painted drawings: big splodgy love hearts, a unicorn, stick-man families holding balloons. In the now-vacated house, they look disturbing rather than sweet.

The first floor is filled with the trappings of a life either being packed away or waiting to be unloaded: plastic boxes, cardboard boxes, suitcases, indiscernible debris pushed up against the windows. Black wooden hoarding bearing the name of a contractor has sprung up around the building’s perimeter, inhibiting the view into the ground floor and garden.

Early imagery of the Winter house heavily juxtaposed the building with the gravestones and statues of the cemetery. On one level this can be read as a striking contrast of the new and unapologetically modern with a fading Victorian fussiness. But there was also something ironically gothic in how the intentionally rusty building echoed the crumbling and time-worn graves that surrounded it. After the building was completed Winter’s friends presented him with a plaque that read “Rust in Peace.”

Today that gothic quality extends to an overall sense of decay and fading presence. The building at 81 Swains Lane is now rusting in ways that it was never intended to. Bits of it are falling off. Windows are slowly turning milky white. Once at the vanguard of what was new, it now appears ghostly and of another time, heavy with the sense of past lives.

The building is one of a growing number of experimental midcentury residences, built either by architects for themselves or commissioned by a small coterie of progressive clients, that are reaching a key turning point in their lifespans. Their original occupants are dying. The remaining family members are selling. One era is ending and a new and complex one is beginning as the buildings find new owners.

For many buildings in London, this would be the point where significant redevelopment takes place. Some might undergo a program of adaptive reuse, more still are simply flattened and transformed by the logic of neoliberal capitalism into new build apartment blocks with a maximum number of units crammed into the available footprint. However, due to many of these pioneering buildings having listed status, or otherwise being cherished by the architectural community, there are certain limitations and awkwardness around them being demolished or drastically altered.

These buildings are particularly concentrated around Camden, the north London borough in which Winter’s house is located. Many architects lived and practiced in the area, making them well placed to capitalize on sites that became available in the postwar era. Added to this was the fact that the borough had a relatively forward-thinking attitude to planning regulations, and at the time was embarking on one of the capital’s most substantial and now celebrated programs of social housing. While from a client perspective, north London and particularly the area around the Heath has a long history of being a hotbed of liberal intelligentsia, which meant individuals with financial means and an appetite for forward-thinking modernist architecture. Projects such as the Housden House on the south side of Hampstead Heath and the Burton House in nearby Kentish Town, as well as various projects built on the borough’s cobblestone mews streets, are all examples that spring to mind.

In the intervening time, the combined effects of a growing market for projects by prestigious architects, scarcity of land, and rising property values has meant that the houses have been pushed into astronomical price brackets. The original cost for 81 Swains Lane, labor included, was £12,421. The guide price when it was listed in 2013 was £3.2 million.

This often places the buildings between the conflicting interests of a new wave of high-net-worth owners who have certain expectations about access to modern conveniences, and preservationists and planning authorities who live in fear of architecturally significant buildings being gutted and filled with Crittall windows, marble countertops, underground swimming pools, and private gyms. (Listing may protect a building to some degree, but they are still vulnerable to opportunism and insensitive refurbishments, as well as typically being in need of significant care and repair.)

Often such buildings get caught in an existential limbo: too expensive and legally awkward to be worth the investment, and too important to disappear. They are liable to sit empty for long periods of time, unable to find new owners or frozen in the red tape and expense of redevelopment, thus leaving a small but growing stock of spectacular midcentury ghost houses.

At present, the resurrection of 81 Swains Lane seems to be going ahead. The confirmed project architects, SHH, specialize in luxury retrofits with a client base that — judging from the languages tab on their website — largely comprises buyers from the Gulf states, Russia, and China.

Being heavily listed means that the interventions are strictly regulated, and work on the existing fabric of the building appears to be limited to improving its thermal efficiency. Still, loopholes always exist. For the time being at least, most of the heavy change is set to take place in the surrounding grounds where the planning regulations are less stringent.

A single-story extension made from cinder blocks and a corrugated steel roof, built when Winter’s wife Valerie was no longer able to use the stairs and deemed “not of special interest” by Historic England, will be razed and replaced with a new guest wing.

Maybe the spookiest feature of the new scheme is a proposed excavation of a long-buried tunnel, formed in the mid-1800s to take mourners from the chapel under Swains Lane and into the eastern side of the cemetery. A section of the six-meter-deep walkway ran through what later became John Winter’s garden; the architect cut it off, backfilling it with waste from the construction of his house in place of a skip. The plan is now to unearth the tunnel, where it will house an indoor garden, sealed under a glazed roof, and, below that — because this is London in 2024 — a private underground cinema.

Despite all the ambitious talk, it is worth noting that this is not the first time that the house has had publicized plans for redevelopment, the last being in 2014 when Ellis Miller + Partners were announced as the project architects. On the day I visited, the construction site was inactive, with the most recent paperwork on the building’s front door dated to 2022–23. So perhaps its time in purgatory is not over yet.

Later that morning, a group of international diplomats and their executive assistants received a private tour through the cemetery led by a woman named Julie. The sound of birds and the smell of wild garlic were both heavy in the air. In between inspecting the graves of the likes of Alexander Litvinenko, George Eliot, and Karl Marx, some of the party stopped to take photos of the Winter house. It was striking how imposing the building looked from inside the cemetery, as well as how quickly it receded from view. At one moment looming and incongruous, impossible to miss, and only a few steps later disappearing almost entirely, now only faintly discernible through the dense foliage of a tree.