GEA POLITI: Is there a particular reason why you switched from painting to photography after a while, like did you feel that painting was old-fashioned or obsolete or out of time?

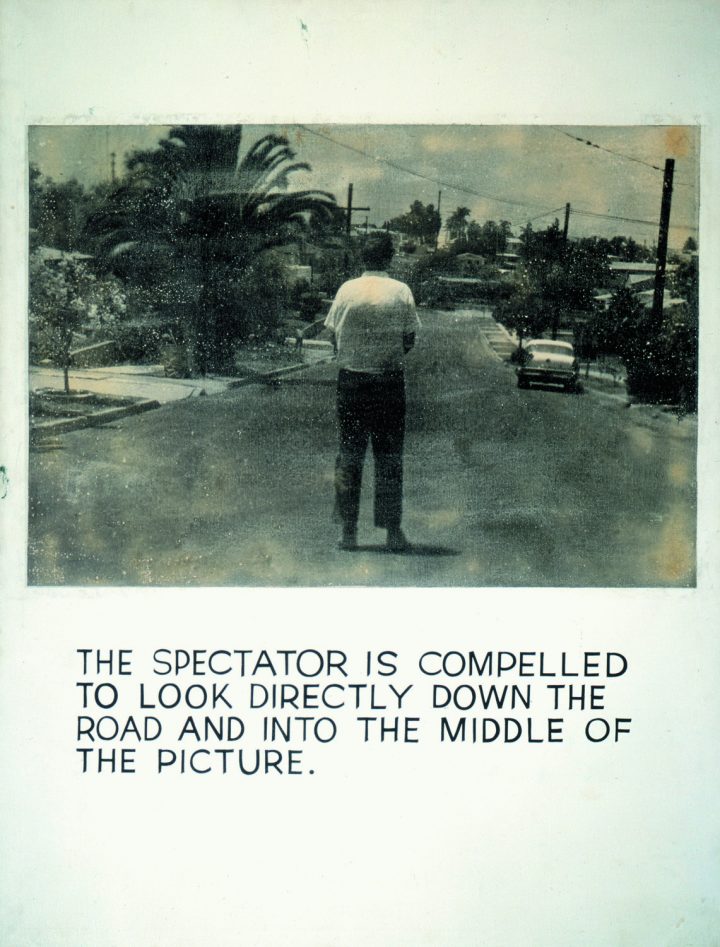

JOHN BALDESSARI: Well, a little bit of that, but there were specific reasons. The milieu I was working with, my peers, were basically inheritors of Abstract Expressionism (but maybe fourth or fifth generation). It did seem to lack a kind of energy. The thing you always get about abstract art from the public is “I don’t get it,” or “My kid could do that.” So I thought, “What would happen if you made things perfectly understandable? Would it work any better?” Well, of course, the answer is no. What I decided then was, “I’ll use text and I’ll use photography because people probably read magazines and newspapers and watch TV. That seems to be a very democratic language.” And so I decided just to give people what they wanted and see if that would be any better. But of course, it wasn’t any better [laughs]. That wasn’t art either.

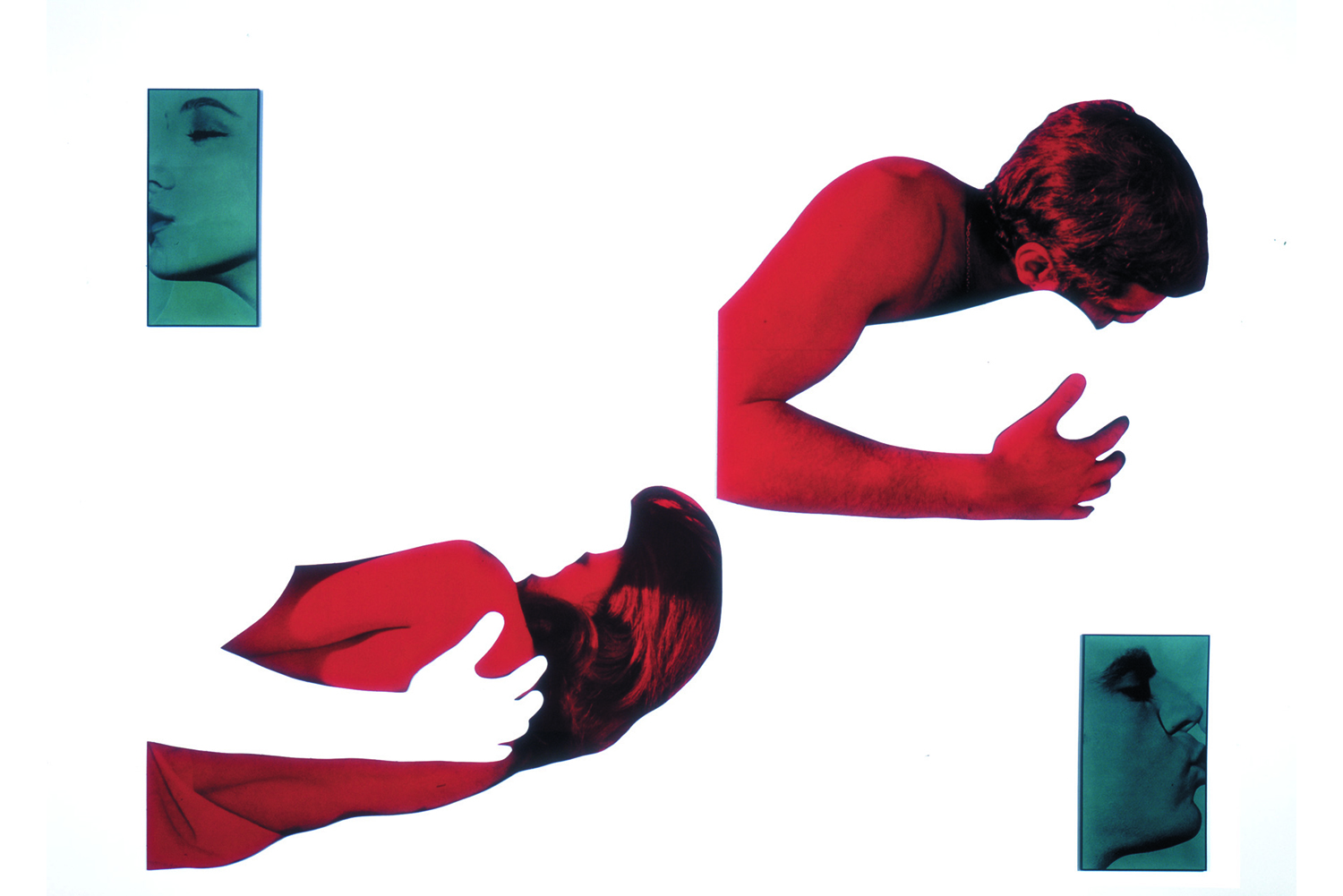

GP: What imagery sources do you rely on for your photocollages?

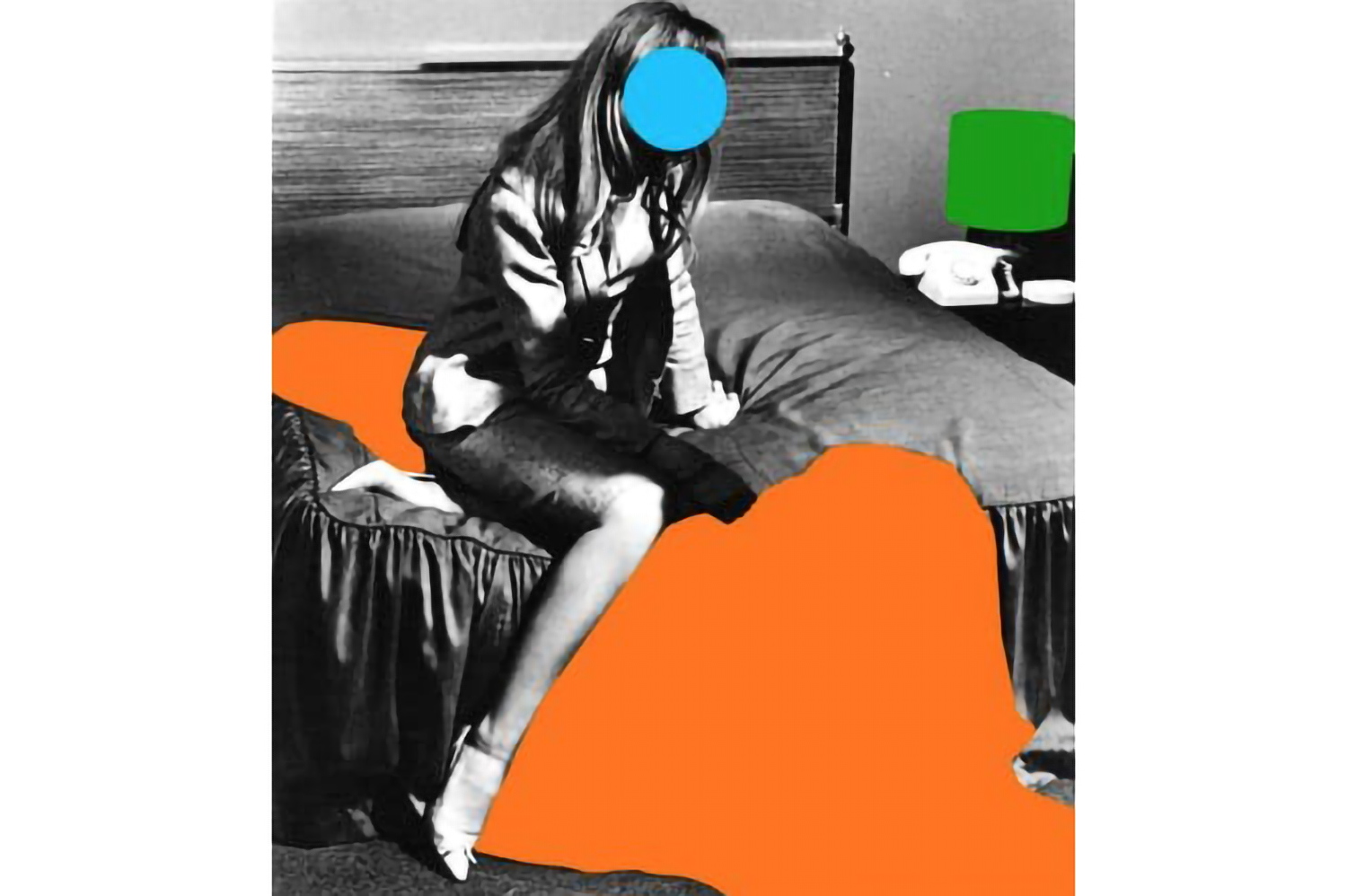

JB: I have big files of found images, either from newspapers or movies or stuff I take, and somehow I can keep a lot of it in my head. I always thought it would be wonderful to have all of those on a computer and say, “Give me any photograph that has a teacup in it,” and it would show it to me. You can kind of do that now. You can certainly get images of teacups. But are they images of teacups in an ambiance? I’m usually more interested in the surroundings an object occupies. Certain kinds of images stick in my head. For instance, I saw a great exhibition of Chardin at the Met, and I noticed he would always have something balancing on a table and coming straight at you, like a knife or a spoon, where it looks like it’s going to tip. So I’ve been wanting to explore that photographically, where you actually want to put your finger in the image and turn it or push it back — to create some degree of discomfort. Now this is something that you’re not going to find images of. You’re going to have to do it yourself. So I think there are certain things I photograph myself because I just haven’t been able to find that imagery. There are some images that I have around that are just in my mind. Like there’s an image that I haven’t been able to use (but I will one of these days) of a guy climbing up a tree. Now, I could go out and ask somebody to climb a tree and I could photograph them. But the reason would be that I remember that photograph. Sure, I could repeat it, but that’s sort of like discovering the wheel after it’s been invented. I think if an image already exists, why replicate it? It’s a complicated issue. Because also I think I’m a real formalist in some way, and a lot of times it’s just how the darks and lights distribute themselves, say, in a black and white photograph. I like it for a purely abstract reason.

GP: Do you think that some of your works happen by accident or by luck?

JB: I don’t think anything is by accident. Do you? I just don’t. I’d like it to look that way, but I think it’s all very calculated. Actually, I heard a talk by Frank O. Gehry the other night, and he has the same problem. People think his early houses look very casual because he used plywood and chain-link fence, and he said “No, that’s very aesthetic. I’m a very classically trained architect, and I pay attention to every detail. So if it looks accidental it’s because I’m planning it to look accidental.”

GP: There are other artists that say everything happens by accident. Like Francis Bacon, for example — he always said that all his paintings and all his works happened by complete accident. I don’t believe that either.

JB: Well, it sounds a little disingenuous, doesn’t it? It’s a good sound bite, I suppose.

GP: [thinks about it] I guess so. Do you remember the moment when your life changed from—

JB: Oh yeah.

GP: When was that moment?

JB: First of all, I thought that one did art as a vacation, not as a vocation. So I thought I would just teach in school and paint when I could and have a family and pretty much that. And then my life changed. It wasn’t by accident. I think it was just one of these things of being in the right place what we call a community college, and the University of California moved into San Diego with a new campus — UC San Diego — and I met socially with the new chairman of the art department they were forming there. I met him on several occasions, and we sort of hit it off. And I just got a call from him, and he said, “How would you like to come teach for me at the university? I’ll give you a studio. I’ll give you fewer hours to teach and better pay.”Well, who can say no to that? The rest of the faculty were from New York, and I didn’t know anything about art in New York at all.

GP: You never lived in New York?

JB: Well, I have, but not then. So all of a sudden I was making these social contacts with people in New York and meeting other artists. So that was something I could have never done on my own. Then when CalArts started here in L.A., in 1970, the same person asked me, “Will you come teach for me at CalArts?” So that got me to move up here, which I probably never would’ve done either. I’m not very adventurous.

[laughs] And that changed my life because I was meeting not only artists from other parts of the world but musicians, actors, filmmakers, writers — from all over. The other thing that changed in my life was that I always thought art was kind of masturbatory.

GP: Masturbatory?

JB: Yeah, it didn’t help anybody. And I have a very strong religious background. I wanted to help feed people, help shelter people. All those classic things. And I think teaching is one thing that helps people.

GP: Is there a particular time when you felt you were really helping someone?

JB: I happened one time to be teaching juvenile delinquents in what they call “honor camp,” where there are no walls, but if they try to escape then they go to prison. It’s up in the mountains. They live there, and the teachers have to live there as well. I have a credential, so I can teach any subject at that level. But you know, these are criminals. They’ve got an attention span of about five minutes in a forty-five minute class. So it was real hell. But then one of the kids asked me one time at night if I would open up this arts and crafts room where you did art and whatever you wanted, and I thought really quickly and I said, “You know, if you pay attention in class I’ll give my time and open it up at night so you can work in there.” And it worked like a charm. And I realized these young criminals cared more about art than I did. It was more necessary for them. So I thought, “Well, art must do some good somehow.” And that’s what made me commit myself to art. I still don’t get it any more than that, but I do know art does people good. I’m not sure how it works. It seems to be necessary.

GP: You’ve passed through four generations of artists. How would you say that the art world has changed from that time?

JB: Well, I certainly think there is more pluralism. When’s the last time two artists got into a fight over their aesthetic differences? You can’t even think about it, but it used to happen!

[laughs] See what I’m getting at? I teach half time still, and I don’t see any dominant mode. I just don’t. Everything seems to be available. I also think more careerism has come into art. Not that I’m pure — by no means. But in my generation there wasn’t any money around to speak of. If you sold anything it was a big surprise, and you called all of your friends and you went out for dinner and you got drunk, and that was it for whatever money you made. But now it’s a career, and you read about art on the business page and in The Financial Times. So that’s come into it, and I think because of that it’s very easy to get into art for the wrong reasons. It’s a way of having your 15 minutes. If you question any of those people, they’d rather be rock ‘n’ roll musicians, but because they can’t be rock ‘n’ roll musicians, the second step down is to be an artist. [laughs] I don’t think anyone starts out to be an artist. They want to be musicians.

GP: Okay, here’s something my father really wants to know: can you describe for me your usual day?

JB: My usual day? Well, that’s interesting. Okay, you ready? [rubs his hands together] I usually get up at 5:30, and I read both The New York Times and The Los Angeles Times. I make breakfast and coffee and orange juice. Then I come here at 8:00, and then I work on the treadmill there for 30 to 45 minutes for aerobic excercise. Then I have a trainer that comes at 9:00, and we work out over there, lifting weights for an hour. And then at 10:00 Kim and Brienne come, and we go over all of what I call “the fires that have to be put out today,” in other words, the urgent things. Now I’m working on a book with the critic Hans Ulrich Obrist. He’s putting together a book of writing and notes of mine, so I’m having to edit and go through all this material. But there’s always more than one project. I’m working on a show for Marian Goodman in New York for November. And the collaborative video project with Lawrence Weiner and Juliao Sarmento is now complete and showing at the Centro Cultural de Belém in Portugal. I’m working on a show for the Deutsche Guggenheim in Berlin for October. And I have retrospective shows coming up in Vienna and Graz and Barcelona and Nimes which includes an outside billboard project after that. Then the next shows are Margo Leavin, Los Angeles, and Mai 36, Zurich, Switzerland.

[laughs] That’s what I’m working on. Okay, then at 6:00 we quit here, and I immediately go to my house and sit on the front porch and have a martini. And then at night is when people passing through town, like yourself, have dinner. And I get to bed usually around 10:00.

GP: That’s a lot.

JB: [laughs] Now tell your father he has to tell me about his day. And we can compare notes. But tell him I keep having a difficult time planning to have any fun. That’s always at the bottom of the list somehow. Tell him to tell me if he has any idea what to do about that. Living in Italy would make it easier, I know.

GP: Not in Milan anyway.

JB: Well that’s true, not in Milan.

GP: Do you watch a lot of TV?

JB: Not really. I like looking at movies.

GP: Did you ever think of writing a screenplay?

JB: I’ve done some movies, you know, artist’s movies… You mean like a commercial one?

GP: Yeah. Like Lord of the Rings.

JB: Yeah, I think I’m too perverse to do that.

GP: Have you ever worked when you were drunk?

JB: Yeah, no. Drugs, drinking, back in the ’60s. [laughs] But now I can’t take it anymore. But I don’t know, maybe on drugs I could work — cocaine or amphetamines. Not with drinking, no. Some artists can, some poets. Doug Huebler is an old friend of mine, and I remember he said he always drank a little bit when he was working. He always had to be just a little bit drunk. But I don’t think I could do that.

GP: Do you ever get bored of your works?

JB: No, Boredom propels me. I made a famous piece where I said, “I will not make any more boring art.” And I think it’s the worst thing, but it’s also the best thing because if I get bored more easily than most people, then I’m going to be aware of not boring people. Whereas they probably wouldn’t notice. And I think that’s the best thing that can propel your art, when it doesn’t bore people. But you know, I’m putting a slightly large definition on the word boring. You know, I’m saying, “Be interesting.” That’s what I’m saying.

GP: Did you ever think of quitting art and starting in another field.

JB: No, I don’t know what I would do. I wouldn’t commit suicide. I don’t know what I would do.