Ever since the Renaissance, the most complex machines that humans have developed have been used as an analogy for the mind. But the human mind is intuitive and too complex an organism to formalize. For example, the head brain works together with the gut brain. Computers are, by design, deterministic: they follow set procedures. In my recent project Gut-Machine Poetry, the idea is to introduce entropic processes to computing by inserting fermenting foodstuff (wetware) into the guts of a computer.

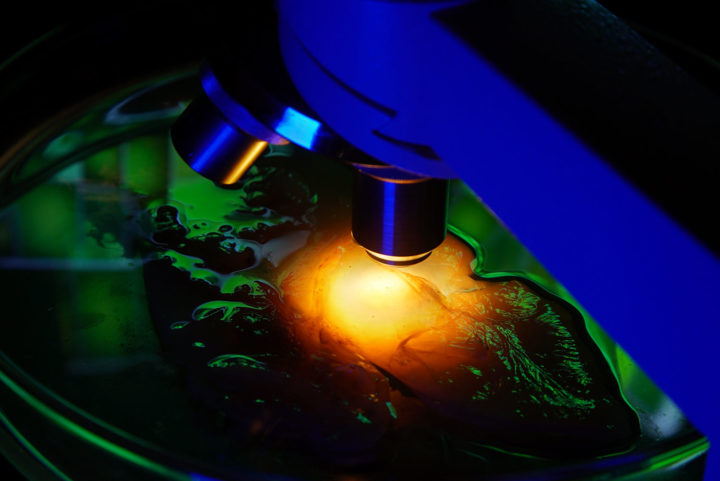

Changes in living material — the stochastic movement of yeast eating sugar in a kombucha tea ferment — are observed through a microscope, analyzed by custom software and used to generate random numbers that interact with a digital database of texts, jumbling them and producing a new kind of language. The jumbling algorithm takes after Jumbo, a program that cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter developed to solve anagrams based on the actions inside a biological cell. In his experiment, letters are combined and broken apart by different types of “enzymes” that, as he describes, “jiggle around, glomming on to structures where they find them, kicking reactions into gear.”

The following pages, produced together with Vincent de Belleval, who programmed the project, provide a glimpse of the mechanisms behind the microbial/machinic poetry culture that was originally presented as part of the Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma’s online collection, with a physical installation at my studio, and later in the video installation Nam-Gut (the microbial breakdown of language) (2017), which includes a voiceover in tongues. The jumbled text is inspired by an ancient Sumerian incantation, a “nam-shub” (see also Neal Stephenson’s science-fiction novel Snow Crash [1992]) that questions the degree of instruction — or performativity — produced by the protocols of computer code and natural language.