I had followed James Bantone on Instagram long before I knew him in real life. I assumed he was an artist, based on the fact that we shared a lot of mutual artist friends and that he attended art school. Yet had I not known this, I might have guessed he was a fashion photographer or a casting director or a stylist even, given the high production and creative value of the images he shared. Our correspondence of the last few years began informally and grew naturally — quick notes exchanged via text soon became emails laden with attachments including reference images, PDFs of academic articles, and memes. At the heart of our discussions were the contradictory poetics of identification and a desire for anonymity, and, not secondarily, how Black, queer identity might be demonstrated within these tangled motifs. It soon became clear to me how, by employing certain aesthetic principles of fashion imagery, Bantone is able to exceed the double bind that dictates representation as equal to a kind of personal exploitation: either wearing masks or cast in shadow, his characters remain as obscure figures.

Olamiju Fajemisin: What are the “tools” of the fashion world? Just the word — “tools” — seems to suggest a material literality, that these “tools” are the very objects which make fashion. But even if someone were to cast and dress up a model, pose and shoot them, then publish the results, still, those images may not qualify as fashion photography, to which I would suggest that the “tools” are figurative instead. A reading of your work makes this clear. Your creation of such highly stylized and stylish images is not solely owed to the fact you are executing the logistics of fashion photography — this alone cannot answer for your clear affinity for visual identity and aesthetic composition, the essence of your work.

James Bantone: For me, the “tools” of fashion are the means of production linked to the industry. But as you say, anyone can work with a model, stylist, or makeup artist, but then, why call that fashion? If you were making a movie, you would follow a lot of the same processes, I guess. Also, just because you’re working with designer clothes doesn’t mean it’s fashion. For my last project, Fool of the Month (2022), we did a lot of thrift shopping.

I look to fashion photography to inspire my own style, visual perception, and visual language — how I want to show things to the world. But then, what is the difference between a fashion photographer and an artist?

OF: I do think it has something to do with merchandising — being able to sell something. Your characters’ poses are clearly appropriated from the images of fashion advertisements. They are uncannily positioned, yet we still recognize their body language as modelling.

JB: Well, what does “editorial” mean? What does it mean to do an editorial shoot? I had a conversation with Ian [Wooldridge], and I kept using this word — “editorial” — without really realizing what it meant. Ian was like, “Yeah, but like, ‘editorial’ is basically an augmented reality. You would never look that way in real life.” Everything has to be on top. Perfect. Everything has to have this smell of… feeling of… fashion. Whatever fashion means. It’s a very creative way of looking.

OF: That’s the missing word. That’s exactly it. “Editorial.” The fashion girls on Twitter and TikTok use the word often, sometimes in a throwaway sense. “Very editorial.” It’s about recognizing the high production value of such an image, its commercial function, as well as what it represents of the publisher’s values. All this feeds a sense of ephemerality in the still image which, as Ian says, simply doesn’t happen in real life. It’s why we have these iconic, sublime images of fashion history.

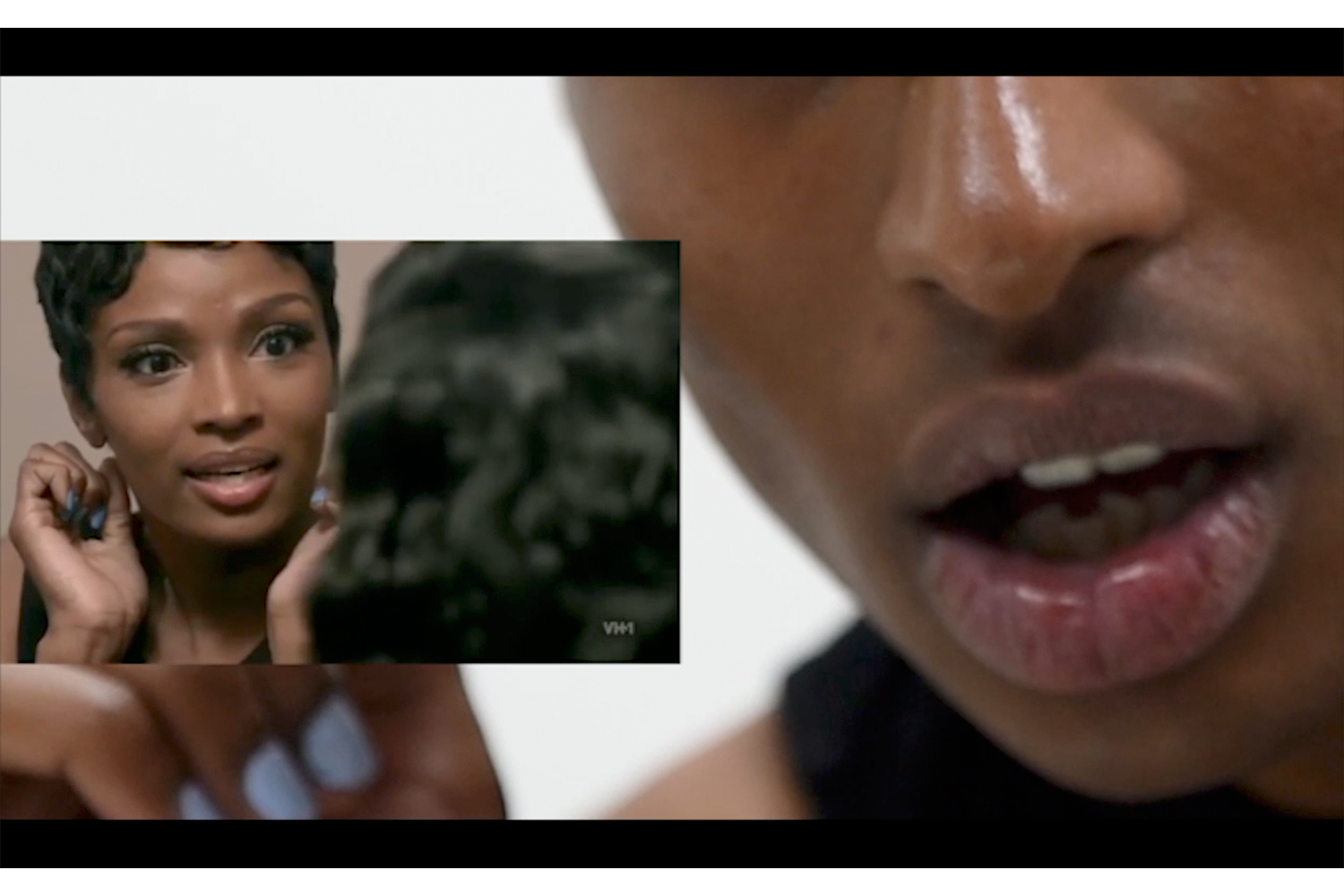

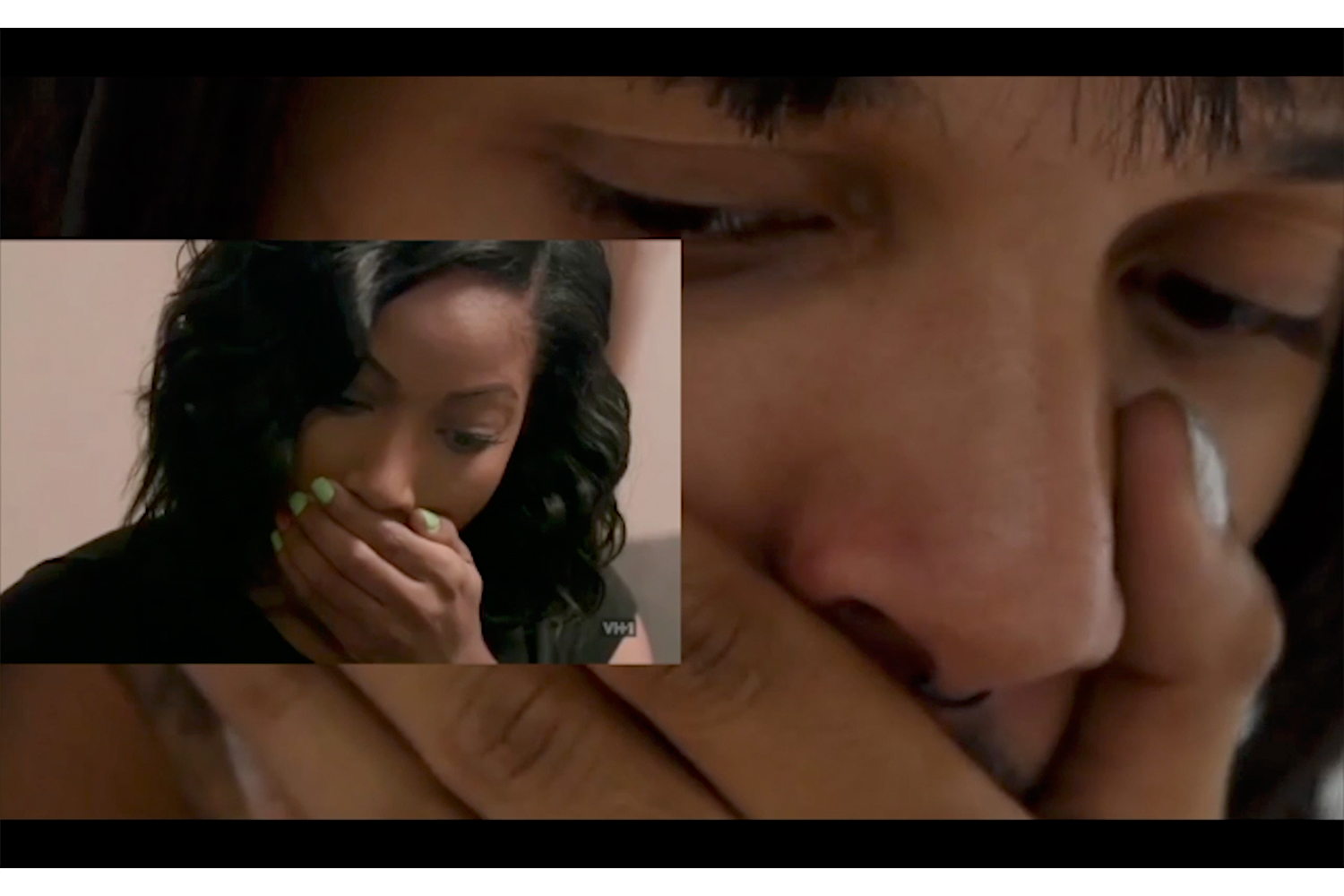

JB: It’s like a performance, and I’m the director. I’m not sure if you remember the show I did with Mohamed [Almusibli] at Dynamo Project Room 13. My first solo. There was a split-screen video of people reenacting scenes from reality TV shows (Wha Ha Happened Was [Erica & Ariane], 2019). We made it in Zurich. Being with them as they recited passages, acting with them, correcting them, exchanging with them… The performative aspect of working with the mannerisms of the body is not talked about much in fashion, even though it’s all about performing this perfection of what it means to be fashionable, or “editorial.”

OF: So, the word is also mimesis. Or, it’s a critique of mimetic desire. Your work repeats certain gestures, forms, and likenesses, but doesn’t copy them with complete accuracy. You’re refusing to appease the social, or as we said, libidinal obsession for new variations on these images, refusing “consumption of the Black body.”

JB: Just as painters or people who draw study the form of the body, I do the same, saving photos from Instagram — I have so many folders on my phone — studying how the body is posed in space, how it’s positioned.

OF: That’s evidenced by the way you use and show the ubiquitous recurring character of your work — the mannequin in a black neoprene wetsuit stitched together with bright thread, sometimes also wearing long-toed thigh-high boots, and always a mask, in your own image. We first discussed this figure when you participated in “Lemaniana” at Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève in 2021, showing Smell My Feelings (2020), and were thinking about what to write about the work. In the end, I said, “Bantone forces the viewer to engage a perverted upward-looking gaze. We peer through the looking glass into whichever realm these abject things may inhabit and are confronted with their fetishistic feet, truncated bodies, and a threatening smile. The grotesque perspective from which these photographs are taken — an impossible underneath — speaks to the metaphysical transgression which takes place when markers of gender, sexuality, and race are falsely assumed.” This atmosphere-creating, installatory aspect of your work feels very different to the photographic portion, which is clearly instructed by a mainstream fashion language.

JB: Well, it’s funny. Smell My Feelings was inspired by a Telfar advertisement, from, like, 2014. It really does come from fashion. But he’s [Telfar Clemens] working a lot with the art people, anyway.

OF: That’s true. Let me look up this ad…You know what it reminds me of? Remember when I showed you that Salvador Dalí painting? The Ascension of Christ (1958). Jesus is seen from beneath the soles of his feet as he rises towards heaven. The effect is very similar, but I’d never seen that Telfar ad before!

JB: I mean, I didn’t even know Telfar existed in 2014.

OF: Crazy…Where did you find it?

JB: I can’t remember! Sometimes I spend hours on the internet and end up coming across stuff like that.

OF: The effect of Smell My Feelings is deeply uncanny. It was shown after “He Said, They Said,” your solo show at Coalmine, Zurich, early last year. You made an installation including wall decals, shadowy portraits showing the backs of the models’ heads, mirrors, and costumed figures, surrounding a single barber chair in the center of a room like an A Clockwork Orange-style recreational torture device or electric chair. The greater installation unsettles. While there are clear, shared motifs across the photographic and sculptural elements of your installations, the result of the former is deeply affecting.

JB: It’s interesting to me, because, what do I call installation? Is an installation a group of works which go together? Or is it one work which causes a situation, somehow? I’m good at putting my own work together in a room, and that’s why I say I do installations, but many of the works can also be considered standing alone.

Yes, at Coalmine, there was one chair in the middle of the space, as the idea was to recreate a barbershop-like situation. That was the first decision to be made — everything else came out of that, and it became this installation which is very powerful.

OF: Something just came to mind: perhaps your installations are so uncanny because of the physical imposition of the viewer within the space as opposed to looking at the space depicted in a photograph. It must be like being on the set of a fashion shoot, seeing the bizarre scene before it’s been imaged through the camera and then further manipulated.

JB: Yes, the effect of being inside the installations, such as in “He Said, They Said” — being in front of this mirror, seeing these huge figures looking back at you as you’re sitting in the chair — cannot be reproduced beyond experience. That “it’s- behind-you” feeling of constant threat.

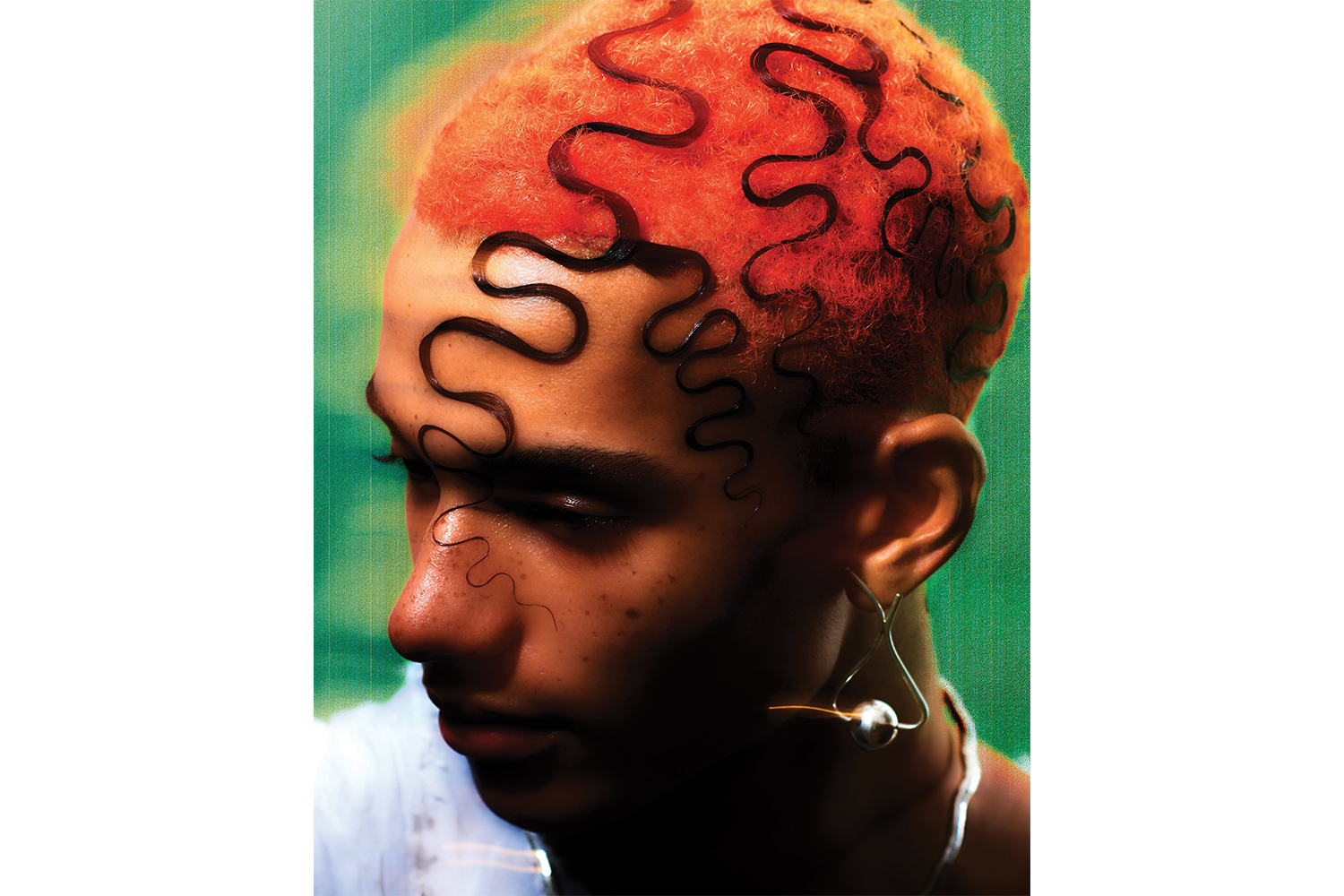

OF: The unmanipulated “lived experience”of being inside the exhibition is as important as (or maybe counter to?) the ways you also distort images, such as the portrait series you showed as part of “Cuts of Love” at Karma International, Zurich (2021). You cut, ripped, and stitched the photo paper, treating it almost like textile, before rescanning and framing the final work. Surely image manipulation can also be considered a “tool” of the fashion world?

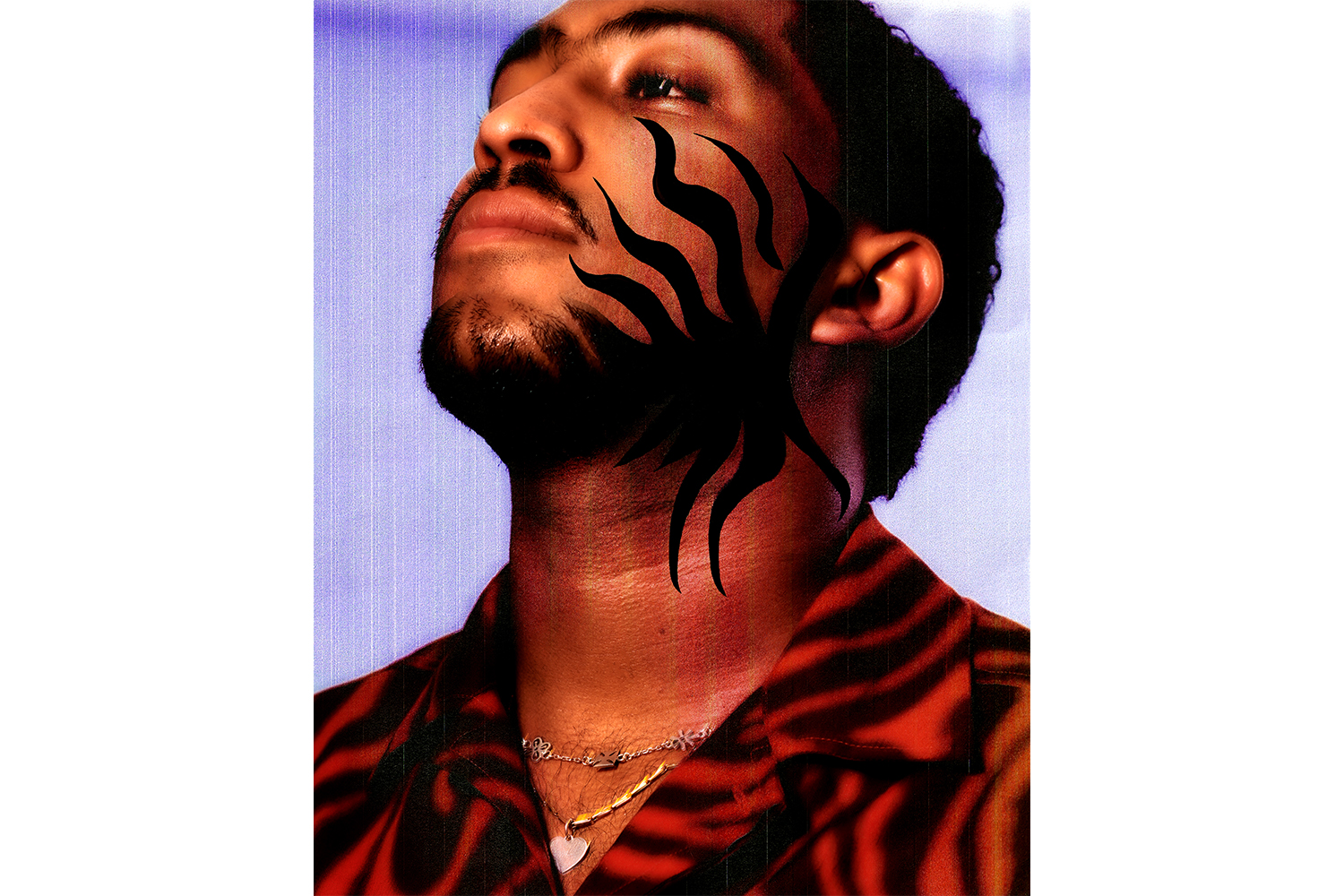

JB: I always like to experiment and play. With “He Said, They Said,” the idea was to play with refusal. To use my own body to block the light from reaching the models. I would place myself in front of the flash so that it was behind my head, and then I would take the picture. My shadow as the photographer becomes an imposition on the work. It’s a reflection on who’s looking at the models. Who’s taking their picture? Who’s objectifying them? Is it the spectator, who comes to the gallery to look? Or is there already a first level of objectification made by the artist? This effect visualizes that thought, in some way. The idea of making it visible is to make the model disappear by way of my own body.

When it comes to “Cuts of Love,” I’ve always liked to play with scanning images. By printing and rescanning the image, I get back some of the texture I lose since

I don’t shoot analogue anymore. I’m able to have an intervention with a material object, but then once it’s rescanned, everything becomes flat again. It’s not

like a patchwork; it doesn’t become cohesive as a single work — everything just goes back to flatness, as it was in the beginning.

OF: It’s like a page from a glossy magazine.

JB: Exactly.

OF: The image is infused with dimension, yet flat. But as you also explained, your manipulation of the image is prepared sometimes before the image is even taken. Intense, bright lighting. Sometimes red, or blue light. Standing so that you obscure the flash. I’m looking at your portrait of Elie [Autins] facing the camera (A Demon Hairstyle Guide, 2020) — almost any perception of their face is obscured, there is very little depth, no contour… it’s almost as if they had been scanned as an object.

JB: Just their eyes.

OF: Exactly. It looks like something I’ve seen in a dream or something.

JB: Really, it’s nothing crazy. Just a red background with flashes directed on the background and away from the subject and one low flash behind myself. Then retouching in post-production, I upped the contrast. I also tend to make all my images very soft, creating a dreamy effect.

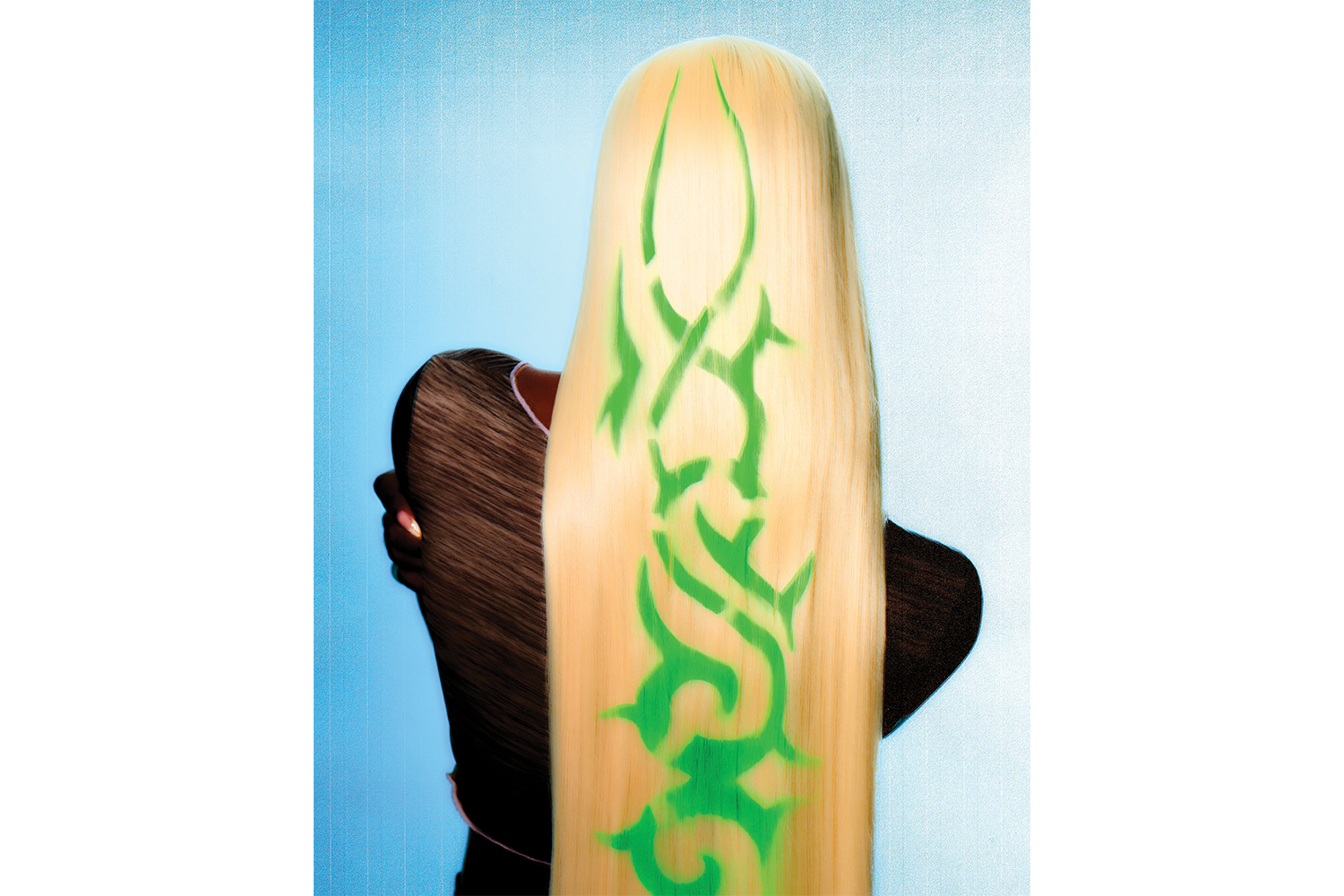

OF: Given the steady realization that the master’s tools cannot dismantle the master’s house, that is, that we (Black people) cannot photograph or image ourselves to liberation, you seem to have found an out in your work.By appropriating the “tools” of fashion and sometimes perverting their application, you’re approaching a new method of representation shrouded with layers of refusal — the masks and tight suits which reveal no skin; sometimes you allow your models’ hair to cover their face or pose them facing backwards, other times you intentionally stand between them and the flash, barely hinting at your presence. Plainly, you are refusing the identification of your subjects and thereby refusing their exploitation.

JB: I wonder if I cracked the code, or if I did it unconsciously, but I’m not sure if I’m playing the representation game, or if I actually détourned it. For the latest series shown this year at the Kiefer Hablitzel Göhner Art Prize in Basel (“Fool of the Month”), you can see the models’ faces for the first time. Can I ask you a question?

OF: Go ahead!

JB: Are the works popular because they’re shown in white spaces?

OF: Well there’s always that.

JB: Is it working out for me because I’m a Swiss boy of non-Swiss origin showing in Switzerland?

OF: Maybe, but still, you’re not giving up everything they want! If we think about libidinal obsession in visual culture — this is particularly evident in Western Europe, where institutions cling hungrily to their piles of looted artworks and precious objects, like ethnographic collectables — the desperation to be “in possession of” an image or likeness, whether literally or in terms of just looking, drives the appetite for so-called “Black art.” Your work denies this appetite in that it, through its many strokes of refusal, can be described as “post-Black,” as it is deeply concerned with redefining complex notions of Blackness while opting to assume an oblique means of representing the Black subject. Some of those are Thelma Golden’s words.

You do not offer the satisfaction of identification or ownership. You refuse

to show face, or fate for that matter. I think this is exemplified in Terminal Irony (2021) shown at Karma International. The mannequin’s head is beyond the plane of the mirror, his hands push against the reflecting image, and we hunger to be able to see beyond the event horizon. Maybe the white viewer hungers more.

JB: And with “Fool of the Month,” which is fully in your face? Did I not give something away?

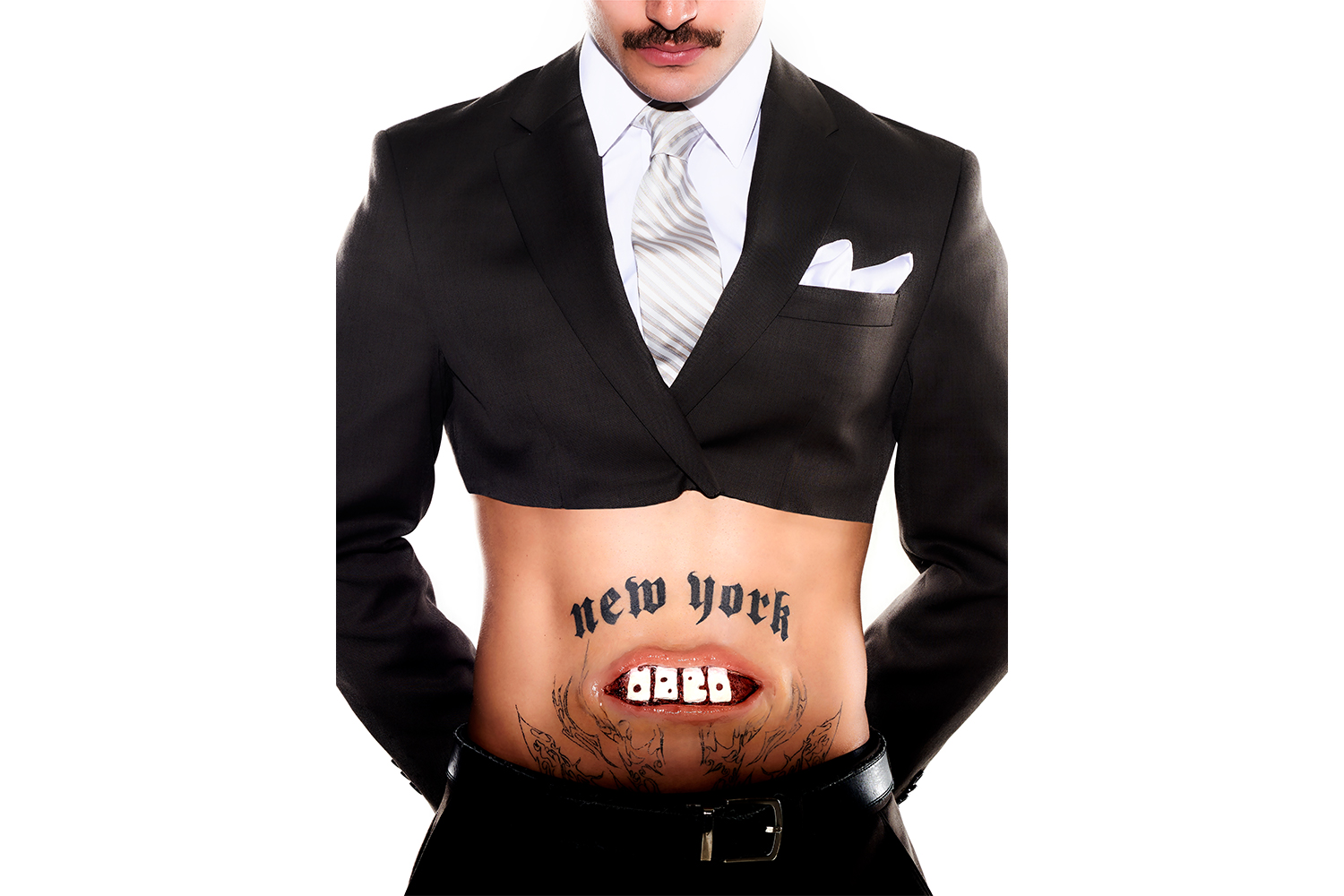

OF: While you can make direct eye contact with the models, or characters, in this series, the imposition of the grotesque, oversized prosthetic mouth de-characterizes the subjects as human, so to speak. Though I can look into them, I don’t want to — or cannot — trust their eyes.

JB: When I started working with prosthetics, it was more instinctive, but there is such a long history of prosthetic use — from their development, following the Second World War, as bodily replacements, to being able to modify the body in any which way, temporarily. “How far can you go in extending and subtracting from the human figure before it ceases to be itself?”

OF: That hits the nail on the head.

JB: It’s from a Guardian article.1

OF: So, you extended your usual representation of the human figure by revealing your characters’ eyes, but then, you altered their figure drastically in another way. It seemed clear, in earlier works, that these figures were human somewhere, back there, in the darkness. But now that they’ve come into the light, and look very unlike how we might have imagined them, another layer of refusal is added. Where you grant us light and vision, you take away personal, even human identification. It’s pure cinematic horror.

JB: Well, when we were talking ahead of “Cuts of Love,” I was already leaning towards ideas of horror, abjection, and certain cinematic aesthetics, but it wasn’t until Basel that my work truly started to head in this direction. Creating a feature film is something I would want to do at some point. Working with video and fashion in this way also makes me think of performance. I spoke with Hans Ulrich [Obrist] last month, and at the end of our discussion, he asked me about a project I haven’t had the chance to do yet, but would love to realize. The idea I have — I’m not sure if it would be a video, or a movie, or an actual performance — is to create a place where people can go and get haircuts, and while they’re sitting in the chair, the barber tells them horror stories. Part of my writing practice, which I’ve left on the side for a while, is to gather captions and tweets and other things I find on the internet, and making horror stories out of them, or with them, then putting this script to film, or a performance.

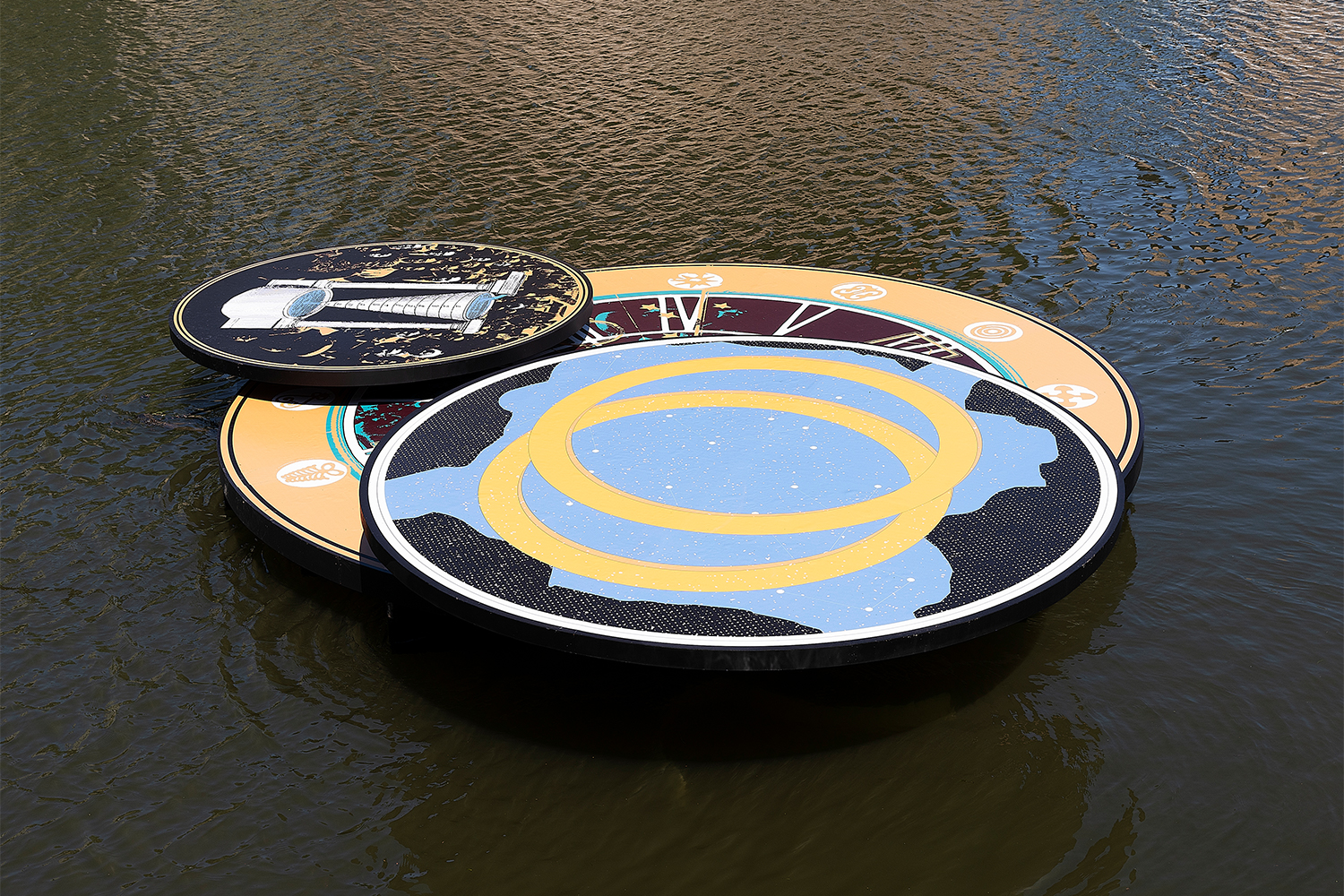

OF: What a fantastic full-circle moment that would be! The first work I ever saw by you was YA MIBALI (For Men) – For Success (2019) at your graduation show at ZHdK (Zürcher Hochschule der Künste). The Nivea ad reenactment, two screens on a blue background. It’s been years since I’ve seen it.

JB: One sec, I’ll send you a link.