In the year 2000, an exhibition was planned for New York’s P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center that was initially supposed to include the original “Disasters of War” by Francisco Goya alongside a selection of war scenes and other atrocities by Henry Darger. In the center of the arrangement of the works on paper, the large-scale sculpture Hell by Jake and Dinos Chapman was meant to be presented. Security issues with the work as a three-dimensional panorama showing a landscape of thousands of handmade little figures led to the decision that the work was too fragile to transport and that its long-term exposure to a rather young and sometimes impulsive audience might jeopardize its safety.

So, together with the artists, we decided to show a series of large-scale photographs based on the motifs of the sculpture Hell that visualized the lowest points of our civilization: war, genocide, destruction, torture and countless individual scenes of violent acts.

The uncannily brutal and merciless scenes of Goya count as some of the earliest ‘realistic’ depictions of the atrocities of war in history. Darger’s watercolor tableaux combine different layers of innocent hope, unexpected perversity, compulsive repetition, delinquent role play, naive belief, and uncontrollable rage to form a complex vision of violence informed by his regular reading of old newspapers and working as a hospital janitor.

In 2004, Hell was burned when the Momart storage facility in East London went down in flames.

The Chapman piece in “Into Me / Out of Me” is Sex II, a large-scale bronze sculpture that shows the famous depiction of bodies and body parts suspended from a tree in a complete state of advanced decay with countless maggots having consumed the human flesh. This colossal work calls to mind the small ebony sarcophagi that were made very skillfully in the late Baroque period, depicting the height of the bubonic plague through imagery of decomposing bodies being eaten down to their skeletons by vermin.

Large Hollywood productions like Alexander and Troy try to find not only a more realistic way of depicting the battles themselves, but also the devastation, blood and misery of the aftermath, both from a bird’s-eye-view and in detail. The 2005 HBO series Elizabeth I features a scene in which several traitors are publicly tortured and killed by having their stomachs scratched open and their bowels wound slowly onto a spindle. While the mere image of this on television forced me to leave the room, it is harder still to imagine how one would react if it were to actually take place in the public eye, right in front of you.

In fact, acts of public torture or executions must have left some of the strongest impressions on an audience that was not already numbed by a proliferation of outrageous images of suffering, brutal accidents and war seen on television every day. But even so, there must be a great difference between being confronted with a scene like this in real life versus ‘only’ through the media. In Elizabeth I, the audience in the background actually seems quite detached, somewhat interested but not too shocked or empathetic at all. In fact, torture and publicly exposed physical violence were acts that would have required a precise skill set and certain predisposition. The act of quartering, for example, was aimed at keeping the victim alive for as long as possible while certain body parts and inner organs were gradually extracted before the final amputations led to the actual death of the tortured.

As unimaginable as scenes like this seem to an educated audience today, confrontations with such misery and suffering must have been a daily experience for most of mankind hundreds of years ago. Just a simple tooth infection without painkillers or antibiotics must have been unbearably painful. In effect, individuals living with appendicitis, meningitis and other untreatable infections must have been ‘in hell,’ so to speak, suffering on the ultimate level while their bodies slowly and increasingly gave up the fight.

A more complex situation like intestinal obstruction would have led to cramps and then a decay process starting from the inside out. Once the bowels had stopped their regular movements, their contents could only shift up or down. The body would have tried to get rid of them before the death of tissue inside the still living individual occurred. Seeing your partner, child or neighbor suffer through such a death suggests a strong metaphor of what hell must be like, or is.

After the dissipation of small pox, humanity seemed for the first time in the history of civilization free of any visibly devastating and sweeping epidemics. Viral flu waves still claim countless victims worldwide, but this is largely due to complications of the flu and an already weak disposition, like advanced age or heart problems, for example. The flu is only a catalyst for death — not the direct cause of death like the mysteriously fast-spreading plague was at its time.

When the first public notion of AIDS began appearing in the media in the early 1980s, the uncanny new illness was labeled the “gay plague” very early on. Kaposi’s Sarcoma, a visible black lesion on the skin of the patient, visualized a growing stigma and challenge that our societies still haven’t faced to the extent necessary.

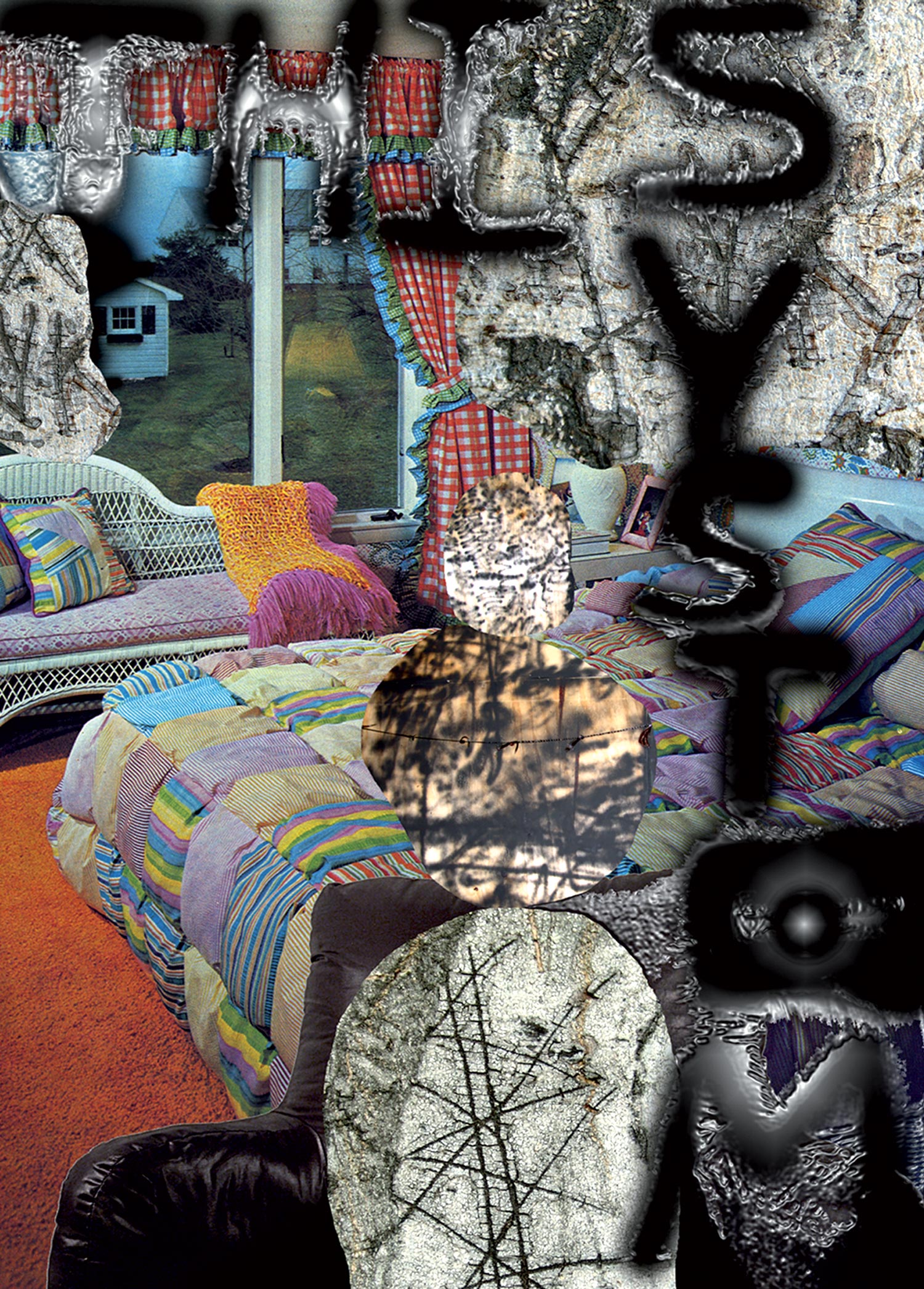

Frank Moore’s 1992 painting Debutantes creates a multi-layered collage alluding to society’s reaction to the AIDS crisis, including the isolation and stigmatization of the disease’s victims. The Spanish fly, an ancient torture device, is positioned on a giant pill-shaped pedestal. This imagery is juxtaposed with depictions of figures impaled on stakes before innocent bystanders, children. Phobia and daily reprehension of the weak and dying add insult to injury, oppose freedom with guilt, support with indifference, and caution with carelessness.

At the height of the crisis, many people did not know that HIV is based on a viral infection that, unlike many other contagious illnesses, is solely transmitted by direct intimate or intense body-to-body contact where such fluids as blood and semen are brought directly from one person’s system into that of another organism. Still today, millions of people die of AIDS, and the most simple protection against it seems not even affordable or possible to practice by the thousands of people that become infected every year.

The knowledge of having been infected with HIV was until the late 1990s a countdown to a certain death with an average projected life expectancy of approximately ten years, at which point the patient was expected to lose the battle against the virus and the infections that followed it. Whereas AIDS had the traits of a death sentence and heavily influenced younger generations as they went through puberty, questions of ethically responsible behavior developed alongside feelings of guilt and paranoia.

Today’s medicine, as advanced as it is, still faces enormous challenges despite the fact that the aforementioned stages of hellish suffering through disease and illness might not be so visible anymore throughout our daily lives, in the media, and on the streets. While every single hospital and cancer clinic is in a certain way a very necessary structure, they are also the means by which we hide away such misery, containing and concealing unpleasant realities behind its walls.

Hannah Wilke’s life-size photographic self-portraits document the advanced stages of breast cancer leading up to her death in 1993. The physical vestiges of her various tests and treatments are apparent, revealing the brutal assault and side effects of the contemporary medicine intended to save her: hair loss from chemotherapy, bruises from injections, stained bandages, being hooked up to machines and penetrated by tubes. She even had herself photographed seated on a bed pan, so as to portray the fundamental helplessness that comes along with the systematic attempt to prolong and save life — and by the same terms, an extended period of narcotically controlled pain.

Physical pain is often paralleled with psychological fear, anxiety, and suffering. Caught in the vicious cycle of the nightmarish realms of phobia and angst, it governs one’s world entirely. Drugs again seem to be a rather ‘modern’ way of dealing with this kind of hell — a hell that is happening to an individual but is not willingly or maliciously inflicted by another. States of deep depression and strong fear might already equal in their anticipation and presence a suffering that could be described as hellish. Before the introduction of psychotherapy and even psychopharmacological influence, these states of mind must have been utterly intolerable, marking an extreme of the inner anguish one can face.

In Bas Jan Ader’s 1971 silent short film I’m Too Sad to Tell You, the artist releases his sadness, letting the tears flow. This image and its title suggest an inexplicable melancholy too unbearable for words. Indeed, it was four years later that he disappeared while attempting to cross the Atlantic Ocean in a sailboat.

Self-imposed torture, in the forms of martyrdom and self-mutilation, is not an invention of performance artists of the 1960s and 1970s, but rather it has profound ancient and religious pretexts. Saint Simeon Stylites, for example, stood on a pillar in Antioch until his feet and ankles started to decay and rot, throughout the hot days and exposed during the nights, just standing there, withstanding time. Such religiously motivated prolonged self-torment pre-dated performances by ritual and duration-obsessed artists. In contrast to these arduous tests of stamina and willpower, the elaborately staged antics of such a contemporary entertainer as David Blaine seem a weak allusion to the traditions of the legendary Houdini.

In her 1973 performance The Conditioning, the first action of her “Self-Portrait(s),” Gina Pane reclined on a metal bed directly above burning candles, and in Sigalit Landau’s video Barbed Hula (2000), the artist stood upon her native Israeli coast and Hula-Hooped with a ring of barbed wire. Ana Mendieta’s photographic performance series of 1973, Untitled (Rape Scene) and Untitled (Self Portrait with Blood), also connect the idea of suffering with a political, domestic, and everyday societal level of violence.

A different approach is added by Bob Flanagan. Like Wilke, found images for illness, and chronicled his death from cystic fibrosis. He was known throughout his life for his performative masochistic experimentations with his body’s limits. In three parts of the seven-channel installation Video Scaffold (1992), created together with his wife, Sheree Rose, Flanagan has incisions made in his chest and drives nails through his genitals. His facial expressions alone, depicted on a separate monitor, help viewers empathize with the pain he must have been experiencing. With the motto “Fight sickness with sickness,” Flanagan engaged self-inflicted violence as lifestyle, performance, and potential statement about the undergoing of medical practice.

The wide range of pain inflicted by purposeful or intentional acts upon another individual suffer is a different chapter in itself. In the Roman Empire, citizens had the right and custom of keeping the physical integrity of their bodily surfaces intact, even in the case of the death sentence. The method of crucifixion through impaling the hands, wrists or feet only applied to persons who weren’t granted civil rights. Transhistorically, few civilizations have successfully abolished torture, the death penalty and other punitive procedures that defile and mutilate the human body. Whereas one condition to be considered for acceptance into the European Union is to have abolished the death penalty, it is still a lawful practice in many of the biggest states worldwide.

All of the above acts are within the order of law and civil life, but once a state of war is declared, or even in the situations of terror and genocide we still face today, there seems to be no variation that is too cruel or too barbaric to be carried out. It is said that the genocide in Rwanda did cost nearly a million lives. The killing there did not take place with anonymous weapons of mass destruction, but was mostly committed in direct contact, human being to human being, face to face.

Afterwards, many of the killers described their deeds as though they had been in a state of rage in which if a victim wasn’t killed by the first cut or hit or shot, one had to fully complete the task, and then move on to the next in a nearly ecstatic orgy of atrocity. Survivors and other witnesses described the situation as very loud and smelly. In a symbiotic relationship, this kind of violence was not only an ‘extreme’ experience for the victim, but also for the ‘executioner.’ The one only exists with the presence of the other.

These were multisensorial experiences that images in magazines could not communicate. A decade later, several movies tried to visualize a fraction of what had actually happened in its full tragedy, but no pictures were available in the vocabulary of the world’s media to gain the attention and reaction that depict the growing aggression between the Tutsi and the Hutu would have needed to deserve. Had these tensions been more widely and accurately exposed, perhaps a different or lesser disaster would have developed. Perhaps this historical lack of articulation is precisely what makes Alfredo Jaar’s 1994 photolithograph Rwanda, Rwanda so strong. Very simply printed eight times in a bold, black typeface, the word becomes a projection surface for the entire disaster, its repetition a chant of late recognition.

In their coverage, journalists reporting on the genocide in Rwanda reminded global audiences about atrocities in the former Yugoslavia. On the most extreme scale of horror, the Holocaust calls to mind a level of evil that was long thought of as having been made unthinkable by the progress of civilization.

Today’s society, no less than any other era, has cultivated a strong distinction between active and passive players of history, between those individuals who are on stage performing and those who sit back in the audience watching and consuming it all. Thinking about the spectacle of gladiator games in the Coliseum where panem et circenses served as entertainment for the pacified Roman populace, onlookers could be there live, in real time, watching people dying, fighting, being heroic, achieving victory, and surrendering to downfall, pure and unadulterated right before their eyes. Today the Internet and TV provide simultaneous access to imagery of disasters, torture, death and violation, loss and victory.

Overweight couch potatoes watch the model-like casts of Survivor or MTV’s The Real World to see how they fight, succeed and fail. The percentage of body fat in the members of the audience in relation to the actors might be very similar to the way things were 2,000 years ago. Consumption is determined, triggered and fueled by access to the spectatorship of a ‘fatal’ moment. In order to be on stage, one has to work hard and suffer pain or embarrassment, insult or even physical injury.

Today individuals are inundated with images of war and terror to an overwhelming degree. Licensed press agencies as well as tourists and accidental witnesses with video recording devices in their portable phones and laptops capture the moment when ‘hell’ happens without any hesitation. Passersby equipped as such are more likely to preserve the fleeting instant in which cruel reality permanently mutilates a victim’s body, physical integrity or dignity.

The images of Saddam Hussein’s sons’ heads distributed throughout the media were treated as trophies in such a way that they could at all levels compete with images of ancient victors hoisting up the heads of their defeated enemies on poles in public gathering places. The moment Saddam was captured, he was penetrated by a doctor sticking a tongue depressor as far into his mouth as it could reach. Penetration in front of the camera was achieved as an act of claiming territory and asserting power.

The historical role model for the fantasy figure Count Dracula was a 15th-century Romanian prince, Vlad III Dracula, or Vlad fiepe∫, which translates to Vlad the Impaler. He was known for punishing his prisoners by forcing them to sit with their anal or genital orifices on a sharpened pole, where the consequence of one’s bodyweight and vanishing muscle strength was a slow and protracted death. Torture is still one of the frameworks in which hell is re-created willingly and purposefully on Earth.

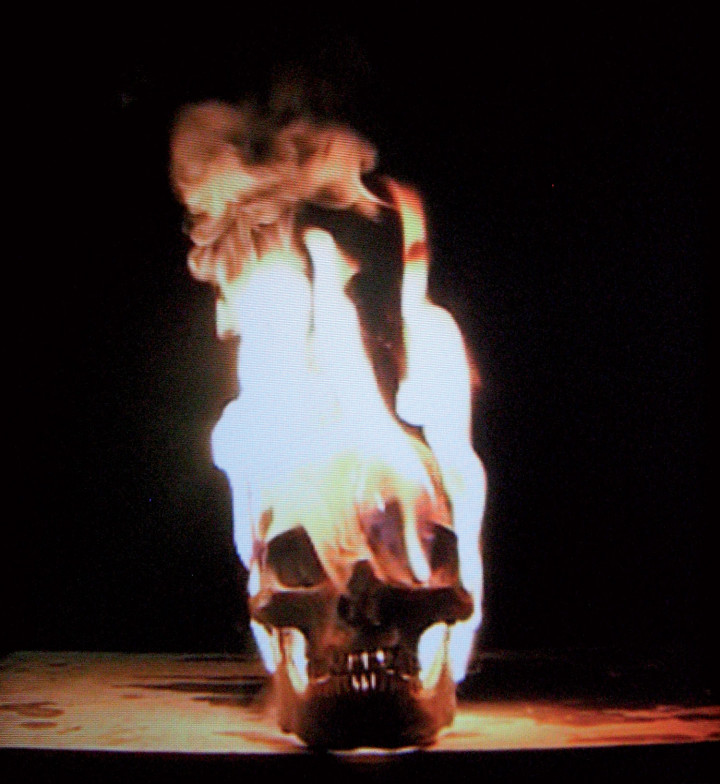

In Paolo Canevari’s 2006 Burning Skull, a human skull is exposed to a strong fire. Gasoline must have been used to intensify the heat of the infinite flames that seem to kill the already lifeless remains of an individual. Amidst the resonance of Goya’s thematic, the skull embodies the iconic fiery depths of hell.

Somewhat less archetypal was Thomas Hirschhorn’s large installation Superficial Engagement shown at Gladstone Gallery in January and February of 2006. Part of the installation consisted of life-size wooden figures that visitors could drill holes into with the aid of a screw gun. Overflowing with images showing victims of acts of violence, war and terror, some of the content was unbelievably graphic in nature, revealing photographs of faces, heads and other body parts that had been brutally destroyed, torn into pieces or blown away by the sheer power of raw force.

Hirschhorn’s exhibition also consisted of a selection of works by the Swiss artist, clairvoyant and spiritual healer Emma Kunz. The task of identifying images of states of being that are among the strongest a human life can experience poses a multitude of challenges to contemporary artistic practice, especially since the Internet is full of images that cannot really find a consensus-driven place in the public debate.