When Marina Abramovic was in the early stages of planning her “Seven Easy Pieces,” the re-staging of seven seminal performances that would eventually be realized in November of 2005 at the Guggenheim Museum, she asked me to organize a meeting with Susan Sontag and herself to discuss how Susan could write a piece introducing and accompanying the performances. In order to find a quiet moment away from the frenzy of the studio, we organized a lunch meeting. Both Susan and Marina loved Japanese food, though I myself am allergic to it.

The meeting began with a welcome sake as Marina explained that the idea of “Seven Easy Pieces” was to reinterpret historically significant performances and extend their life spans by performing them for a new generation of audiences. At that time, Marina wanted to realize Chris Burden’s Trans-fixed performance of 1974, in which the artist was secured to the roof of a car by nails impaling his hands.

Susan was very decidedly against this concept of the willing destruction of one’s physical integrity, and the certain risk of inflicting short if not long-term physical damage. There we sat at the table, our arms and hands gesticulating, guiding the drinks to our mouths, and we talked, discussed and disputed. More sake arrived, and loosened by the alcohol I decided I wasn’t really fragile against Japanese food after all. When it finally arrived, I joined in the ritual of eating, only to be reminded of my allergy shortly thereafter.

We didn’t really come to a resolution that afternoon, but after I excused myself, allowed my stomach to turn, and returned back to the table, we were all too conscious of the situation at hand — aware of the ritualistic nature of the taking of a meal, eating and imbibing in a social context, seated around a table that could easily have been a public symposium for a panel discussion. As we talked about performances that entail the insertion of something into the body onstage, we gradually started elaborating on the concept for an exhibition that would bring together different aspects of the exchange between the human body with material matter, or more simply, “into me” and “out of me.”

Starting with the act of crucifixion that was our point of departure that day, we moved through discussions of ancient punishments and torture methods, mythological and religious narratives of perforation and other acts of violence, daily routines of eating, drinking, and breathing, and complex imagery of reproduction and sexuality. The dialogue came to a close with a conversation about Marina reinterpreting Vito Acconci’s famous 1972 performance Seedbed at Sonnabend Gallery, in which he masturbated beneath a ramped floor.

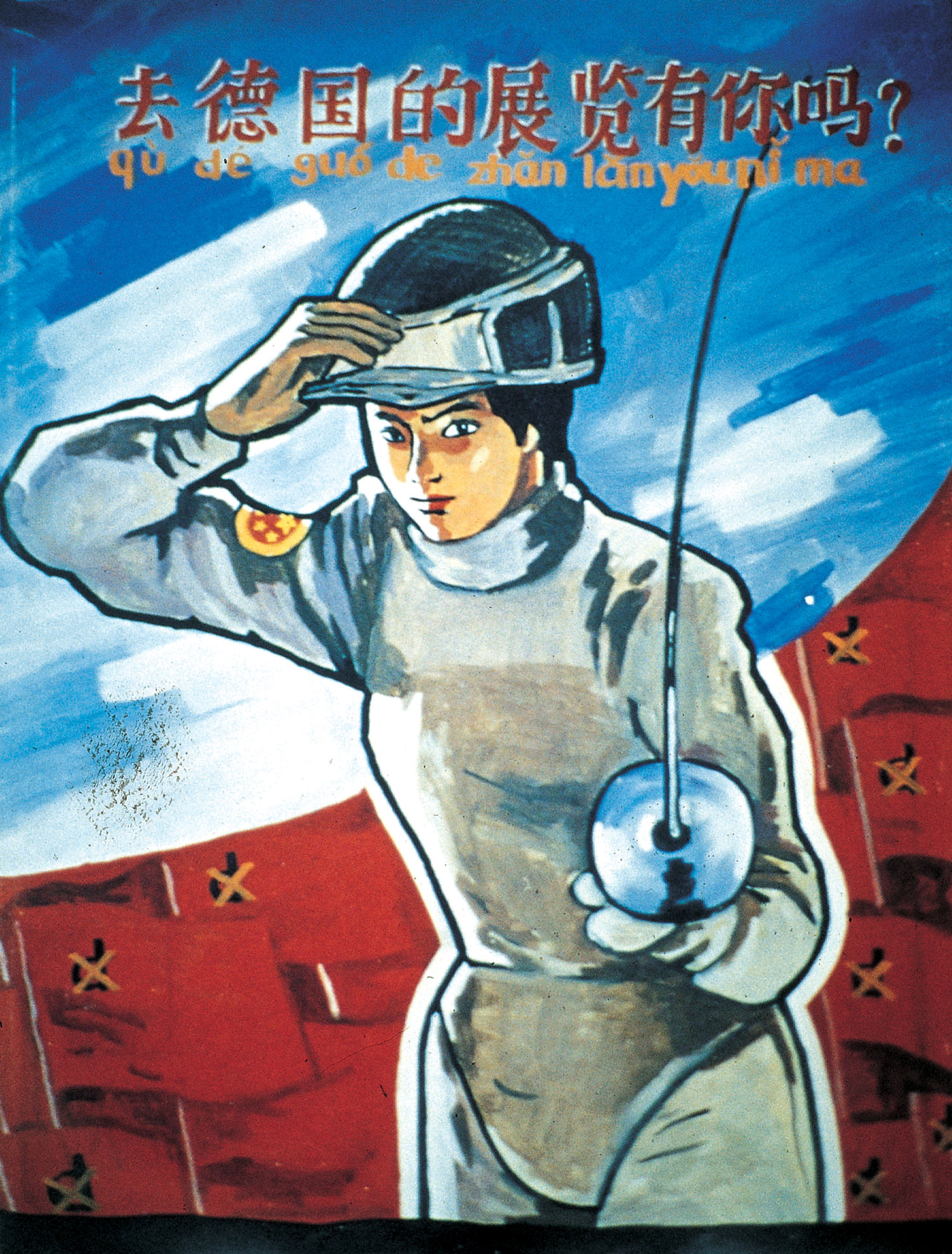

It seems as if more than in the ’50s, in the ‘revolutionary’ ’60s and ’70s artists experimented with utilizing their bodies as the subject and object of their artistic practice increasingly often. New explorations bringing changes in politics, media, technology, and the sciences into mass consumer culture were frequently anticipated and commented on by contemporary art.

Even in trying to focus on such a banal act as eating or drinking, a surprisingly complex collection of images comes to mind. Looking at various appropriations of and reflections on the Last Supper, in the multitude of drawings, prints and paintings that Andy Warhol did after this motif, for example, the stage-like situation of the social gathering at the long table becomes evident. It is nearly the ritual of all rituals: to sit down around a table, to start a meal together, to stay put for the duration until everyone has finished. The idea of a ‘toast,’ speech or possibly even a prayer shared with a familial unit gathered together for an occasion makes the bond a real moment of truth that constitutes the formative nature of one of the most primordial models of civilization.

Whereas in the iconography of The Last Supper the transubstantiation of bread and wine into flesh and blood is visualized, the notion of accepting Christ’s body into the earthly and banal circuit of one’s organism implies that eating is an act of incorporation of more than just food, alluding to ideas about salvation and forgiveness. Manfred Leve’s 2001 photograph Block Beuys captures an image of a Joseph Beuys work, a small clay likeness of Christ positioned beside a Eucharistic host on a plate.

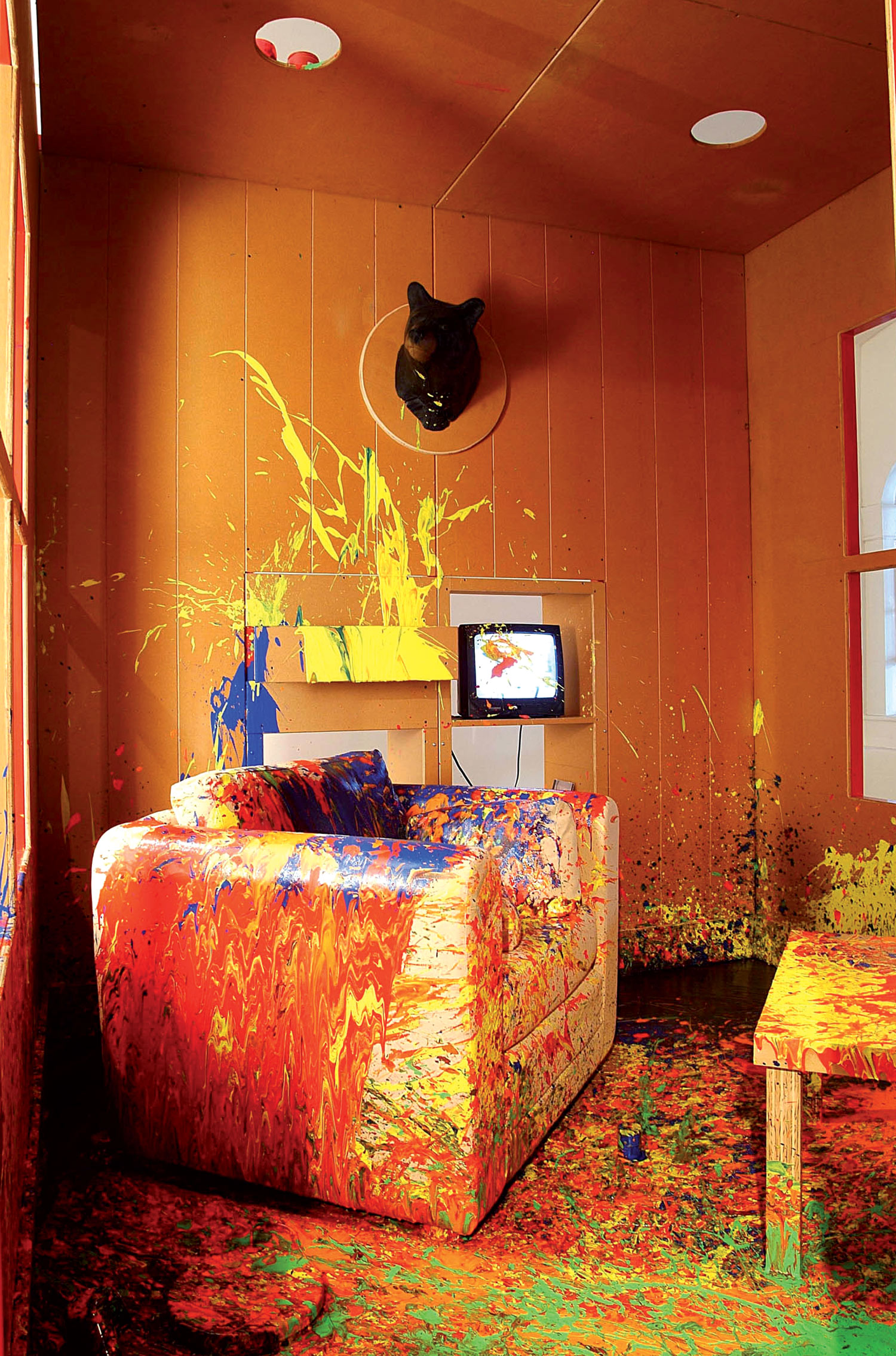

At the same time, drinking and eating are of course the most basic forms of survival, necessary to keep one’s metabolism in balance with the levels of energy consumption that everyday life brings. Our daily routine is structured around this need, through breakfast, lunch and dinner. Gordon Matta-Clark offered more than just nourishment in his Food restaurant that he opened in SoHo amidst the up-and-coming art scene in New York in 1971. Rirkrit Tiravanija also translated the benevolence of the basic gesture of feeding into the relational discussions of 1990s art practice. In Cheryl Donegan’s video Head (1993), the artist tries to swallow milk pouring out of a puncture in a milk container. While the milk spurts out in a stream, she tries to catch it in her mouth without spilling it or compromising her capacity to breathe.

In the history of human civilization, the toothless newborn child is breastfed by its mother in the first stages of life, and at some point is provided with the wet and soft surrogate of food. The mother carefully chews the food first and then gives it to the child, from one mouth to the other. Comparative behaviorism has described this ritual as the origin of the intimate act of kissing. In her piece In Love (2001), Patty Chang exemplifies this paradigmatic gesture through an act of intergenerational intimacy. She simultaneously chews a piece of onion and passes it back and forth between her own mouth and that of her mother’s and father’s, essentially kissing both parents.

Orally coded traditions emerge as means for interaction between the generations. As a result, similar to The Last Supper, the tableau of the dinner table materializes as the backdrop against which knowledge is transmitted from one generation to the next. In the long takes of Warhol’s 1963 film Kiss, it is the famous Factory ‘couch’ that serves as the setting for the first steps toward intimacy, acts of kissing, between various adults.

In medical school one learns that the human body basically has two different kinds of skin, the dry, visible, outer skin and the wet inner skin. A metal placard by Jenny Holzer from 1980-82 articulates this concept of the internal and the external, reading, “The mouth is interesting because it’s one of those places where the dry outside moves toward the slippery inside.” One could actually imagine the body as a complex version of a hose with an inner and outer surface. The main orifices of this hose would be the mouth and the anus, since both orifices are muscular apertures and function as circular sphincters separating the internal from the external. In one Robert Mapplethorpe photograph from the “X Portfolio,” the subject basically brings the proverbial hose full circle by literally kissing his own anus with his mouth.

The passage through the body from the mouth downwards is a motif employed by many contemporary artists. In Pipilotti Rist’s Mutaflor für Wien (1996), for example, a camera travels into the artist’s mouth and out again, only to be swallowed and expelled repeatedly. In Mona Hatoum’s Corps Étranger (1994), the viewer can ephemerally place him or herself inside the artist’s body. In this installation, footage taken with an endoscopic camera fills a life-sized chamber. In Hatoum’s 1996 work Deep Throat, she returns to the socially coded ritual of eating while projecting an image of the inside of her body onto the surface of a dinner plate. The plate is situated on a table, arranged accurately between a fork and a knife, beside a drinking glass.

The act of incorporating the outer world, or at least parts of it, into the inner invisibility of the human body is not only one of the basic requirements of the body’s physical nature, but it also describes the libidinous relationship of the individual with the world of desirable objects of consumption. That being said, one is what one eats, but is one as much as one eats? The ritual of eating is taken to great extremes in many recent works. In Nayland Blake’s 1998 video work Gorge, the artist is hand-fed a variety of foods methodically for the duration of a full hour. In her documented performance 180 Wishes (2002), Nezaket Ekici forces eight kilos of grapes into her mouth in only three minutes. Derived from a Spanish New Year’s custom of eating twelve grapes when the clock strikes midnight, each grape symbolizes one wish. In Anna Berndtson’s I’m Not Scared (2002), the artist puts food into her body while standing on a scale, charting the gradual changes in her body’s weight. At the opposite end of the spectrum, the artist duo L.A. Raeven (twin sisters Lisbeth and Angelique Raeven) makes a statement against the unrealistic standards set forth by contemporary popular culture by starving themselves to the point of skeletal emaciation.

The inherent generosity of our food-based repertoire of rituals is heavily challenged by the ideals with which the media pervades our perceptions of youth and beauty. Such eating disorders as anorexia pose a realistic threat to physical development into adulthood and fertility, while other tendencies can seem to expedite the metamorphosis from childhood into adulthood. The Italian artist Roberto Cuoghi nearly visualized the latter strategy — he ate so much that he developed his father’s bodily proportions. In addition to growing a beard and changing his manner of dress, he even adopted his father’s mannerisms and tone of voice. When his father passed away in 2002, Cuoghi abandoned the transformation.

Experiments with the “into me / out of me” exchange call into question the limitations of one’s own physicality, specifically where familial traditions, expressions of personal intimacy, and their common origins come together as a challenge to the individual’s freedom to self-determinately live the modern or ‘better’ daily life.