“No, I hadn’t heard about Ian Wilson, his life stood as an example for me, his death merely extends its essence.” (Tommaso Trini, email to the author, July 7, 2020)

It seems right to look back on the consistently radical career of Ian Wilson through the words of someone who had been following his work since 1970, from the outset of a practice whose essence overlaps, one might say, with absence.1

Wilson’s work came into its own against the backdrop of the move past modernist and, to some extent, Minimalist idealism, a shift which primarily took place in the second half of the 1960s. While post-Minimalist practices of the era were trying to do away once and for all with modernism’s self-referentiality, incorporating sizeable chunks of “life” by means of new elements such as time, biography, history, and context, Wilson in some ways set out in the opposite direction. Even more than other Conceptual artists of his time, Wilson wanted to push the abstraction achieved by modernist painting to its absolute limit, through what he came to call “nonvisual abstraction,” identifying it as a hallmark of Conceptual art.2 In this effort to break the “silence” of modernist and Minimal art, language played a fundamental role.

While a decade earlier, painters like Gastone Novelli and Gianfranco Baruchello had already begun treating the white canvas as a surface on which to “write,”3 for artists in the Conceptual sphere, language became a favorite means of making the art object “speak” once more. In the wake of what became known in philosophy as the “linguistic turn”4 engendered by the influence of Wittgenstein and French structuralism, language would be used for its analytical powers (Bruce Nauman, Joseph Kosuth, Art & Language), its evocative, imaginative potential (Robert Barry, Lawrence Weiner), and its capacity for humor (John Baldessari). The Conceptualists saw language, first and foremost, as a prime tool for achieving the “dematerialization” invoked by Lucy Lippard and John Chandler; it was a way of minimizing the objecthood of the artwork5, in keeping with Sol Lewitt’s assertion that “All ideas need not be made physical.”6 Language also became a channel for reaching a wider audience and communicating directly with their minds (“live in your head,” as Harald Szeemann put it) while bypassing all forms of mediation; this can be seen above all in the work of Barry, who went so far as to attempt the telepathic communication of thought (Telepathic Piece, 1969).7

On his end, Wilson went beyond the written language employed by other artists, pioneering the artistic use of words that are spoken, exchanged, and disappear as soon as they are uttered. This is perhaps his most important legacy of his work, challenging even the “visual” nature of what is called art: “I present oral communication as an object … I have chosen to speak rather than sculpt. … I’m diametrically opposite to the precious object. My art is not visual, but visualized.”8

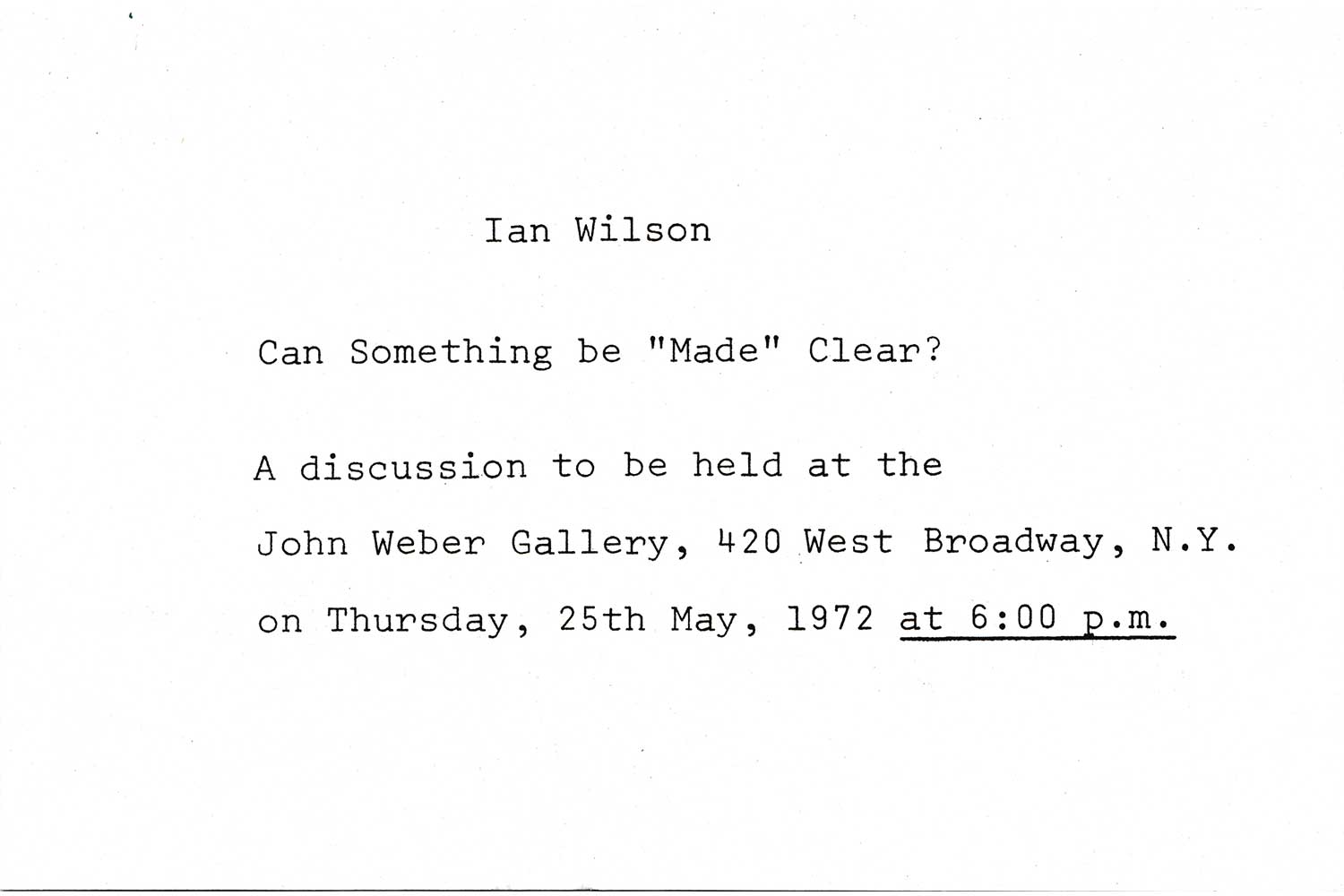

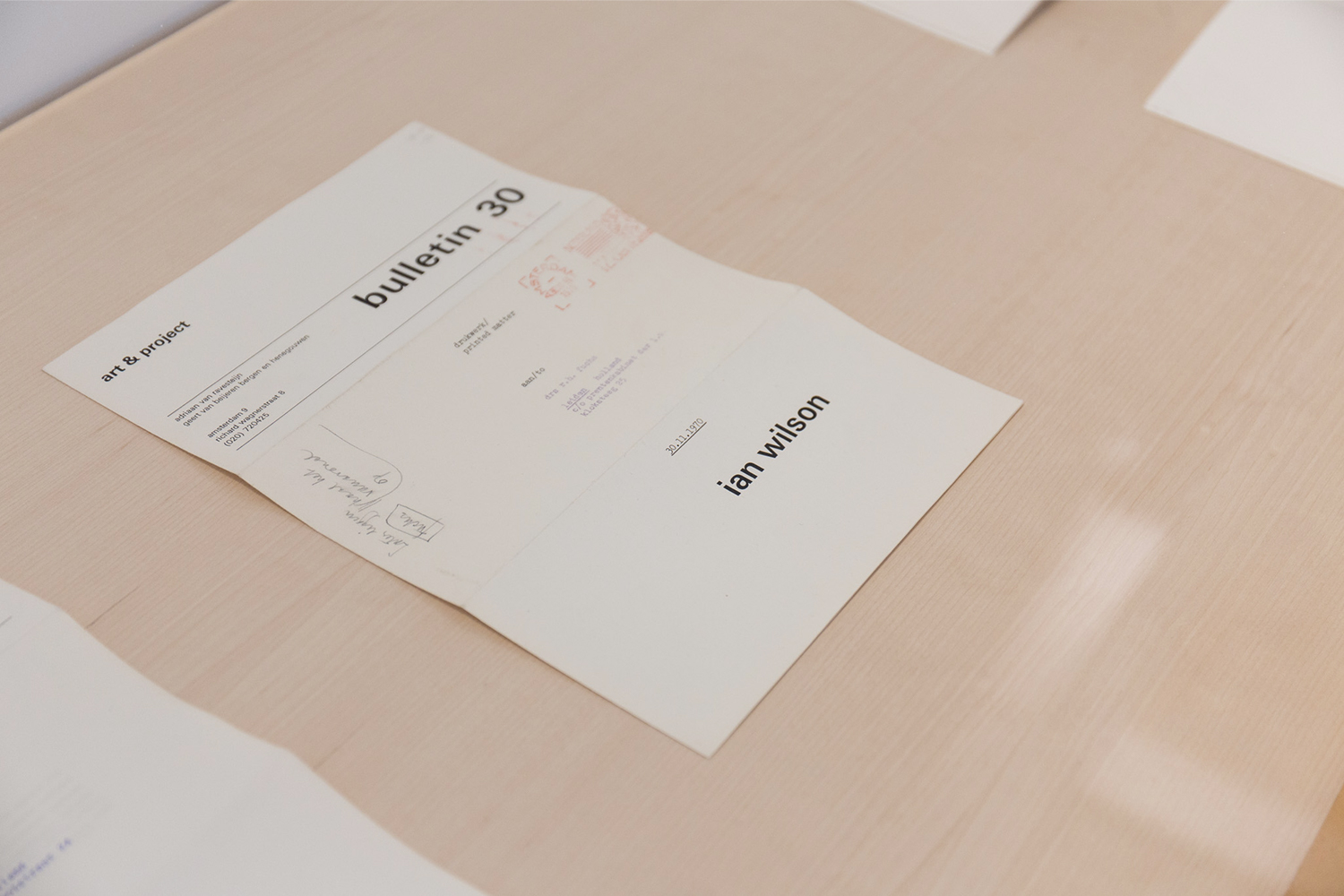

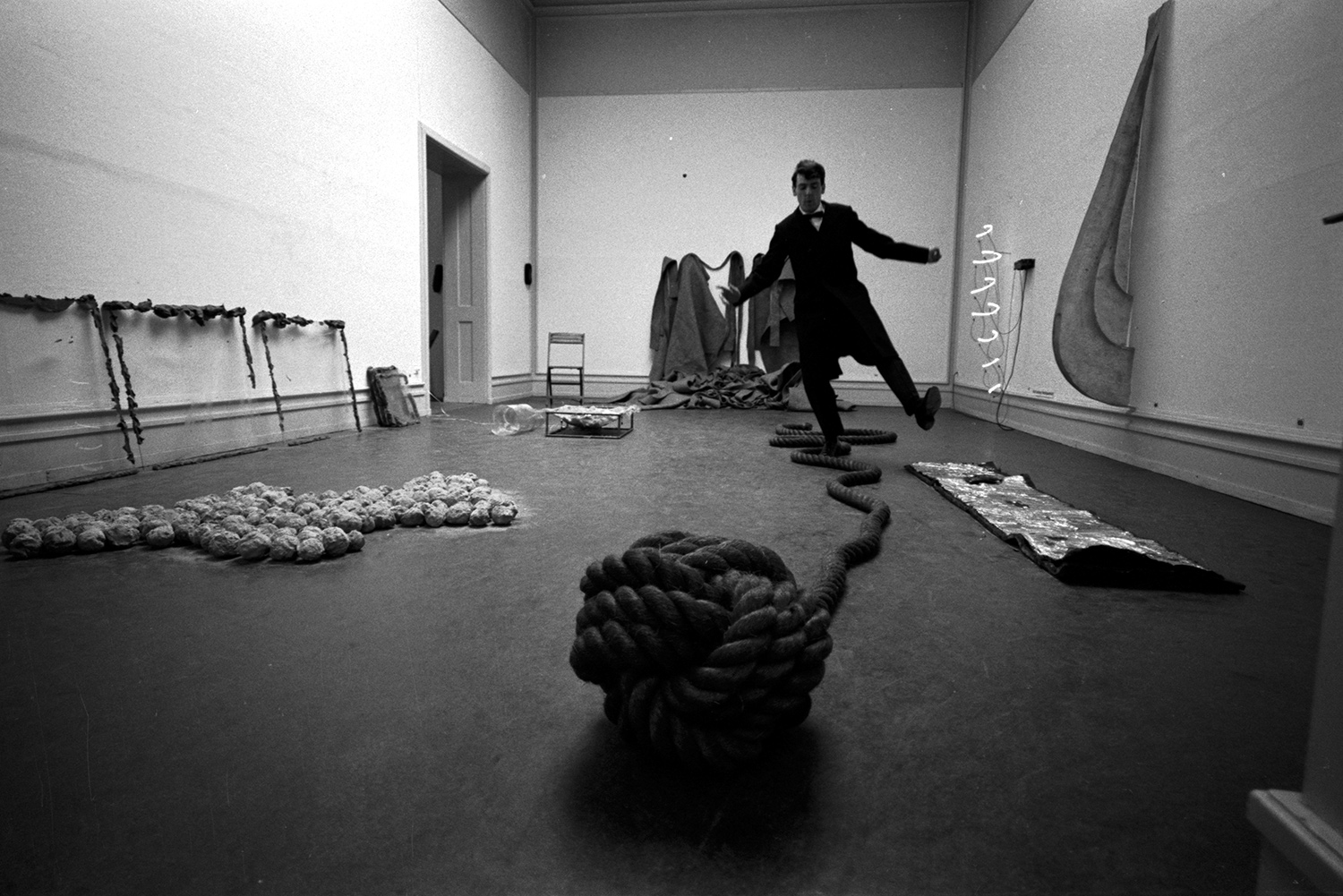

Through the simple act of chalking out a six-foot circle on the ground (Circle on the Floor, 1968), Wilson not only moved away from his earlier Minimalist works, which already tended to have a relationship with their context verging on invisibility (Discs, 1966-67), but came to realize that the discussion of the work could be more interesting than its visual aspect: no longer contemplation but, over time, action.9 Rather than conducting the kind of self-referential inquiry into the nature and language of art that characterized Kosuth (the “Investigations” series) and Art & Language (Index), Wilson’s work turned words into a maieutic tool; the conversations in which he applied it were at first completely informal and spontaneous, but later became structured events with a willing, engaged audience. After experimenting with brief, unannounced conversations involving various random participants, centered first on the word “time” (for about a year, starting in 1968) and then on orality (1969-72), in 1970 Wilson began to hold publicly announced conversations in art galleries, museums, and collectors’ homes.

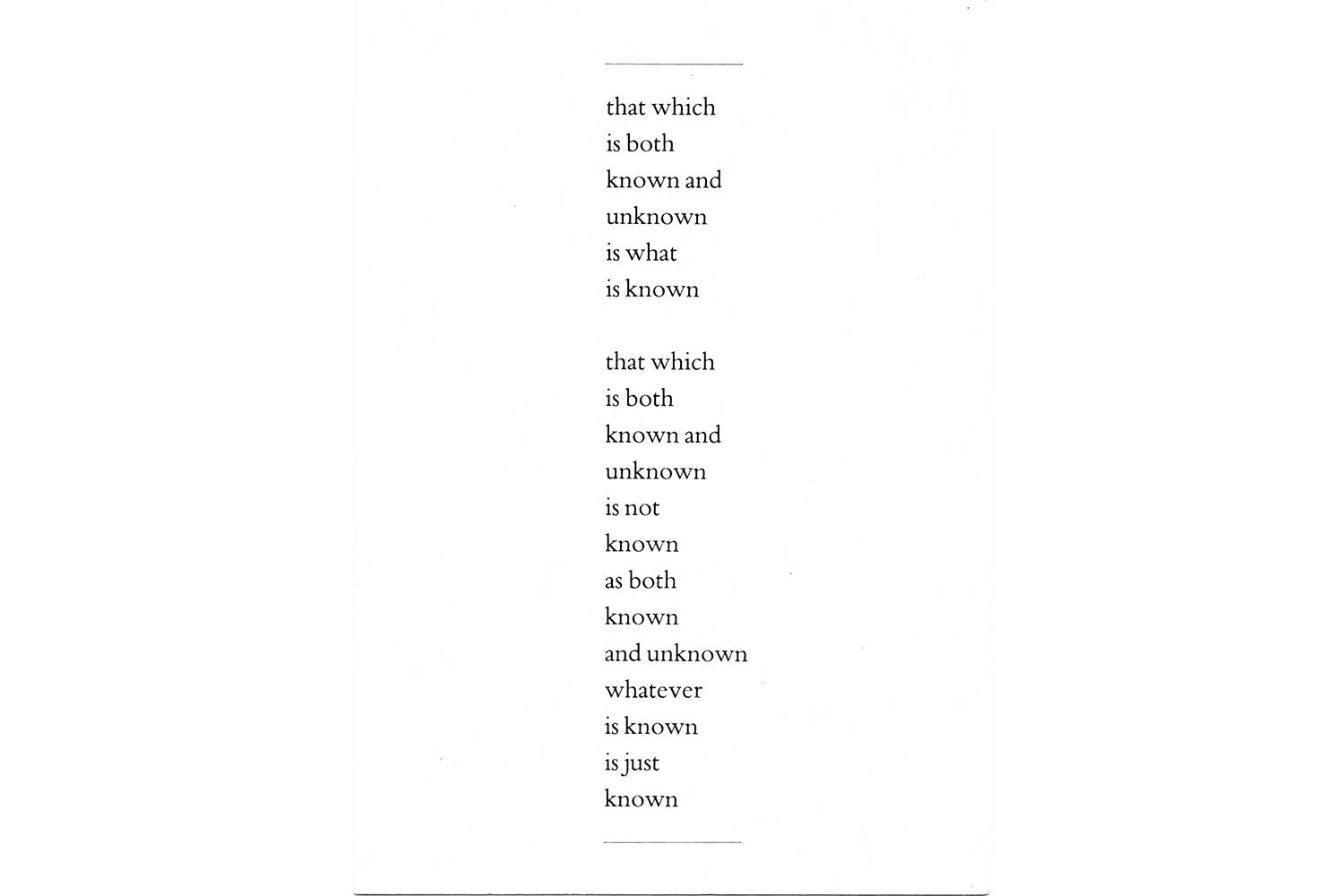

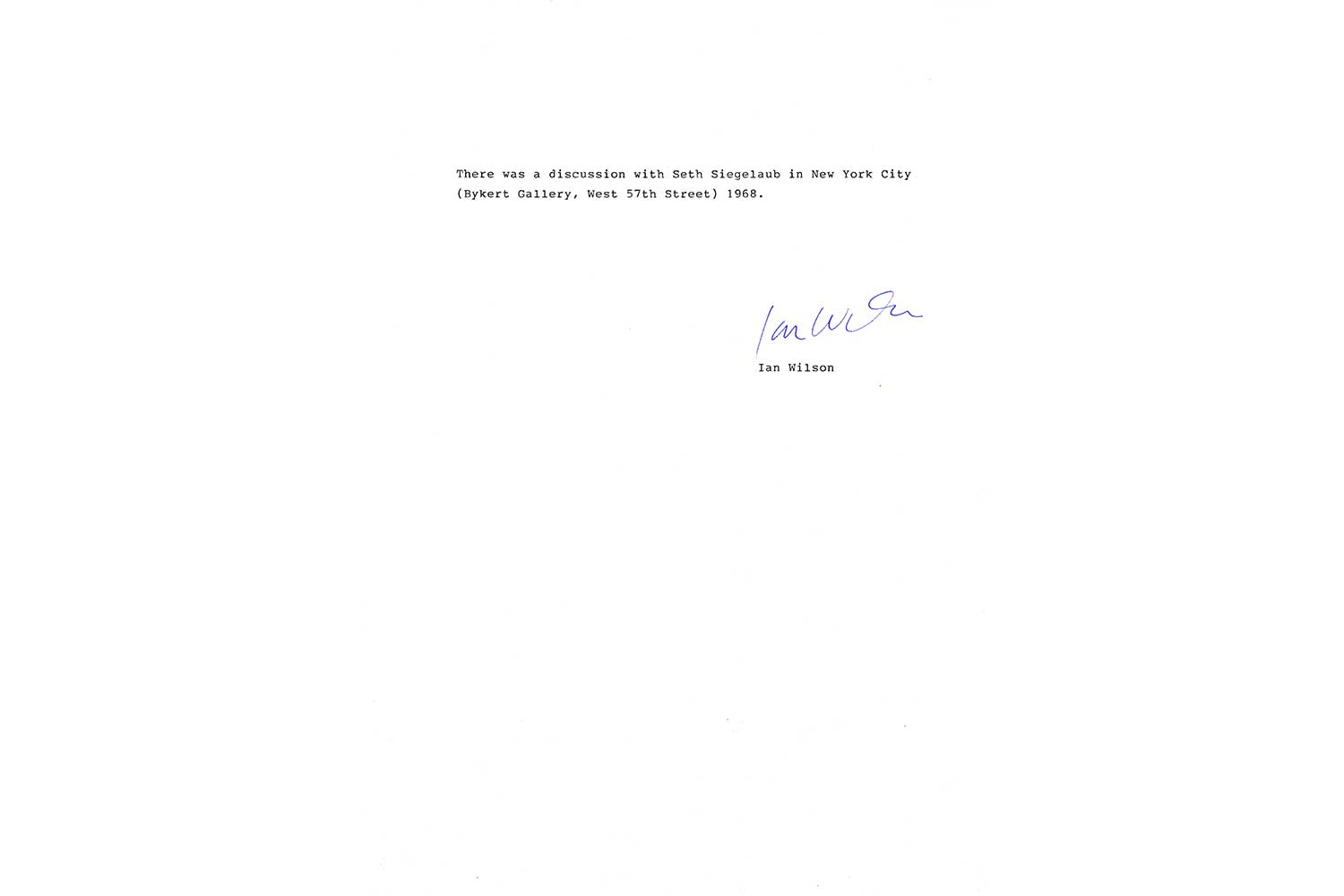

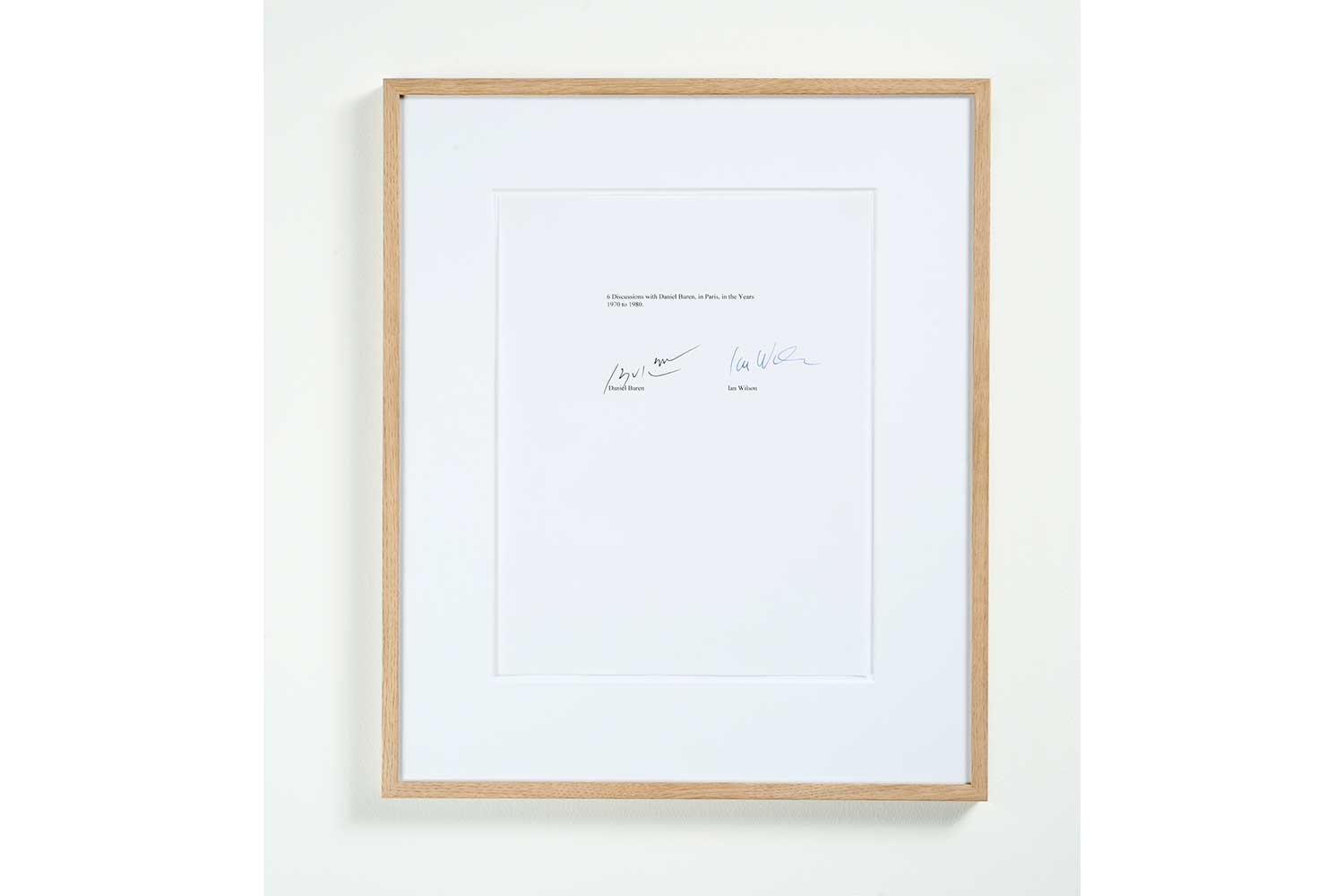

Focused on speculative themes such as “the known and the unknown,”10 and, from 1994 to his death, “the absolute,” Wilson’s discussions were “forums for deliberation and debate”11 employing methods similar to Socratic and pre-Socratic dialogic orality. While Socrates’ speculations were put down in writing by Plato after his death, Wilson ruled out any visual or written documentation of his discussions, so as to avoid “removing the viewer from the discipline of searching for the abstract nature of the truth.”12 Only laconic certificates signed by the artist bear witness to the event and generate an object with monetary value.

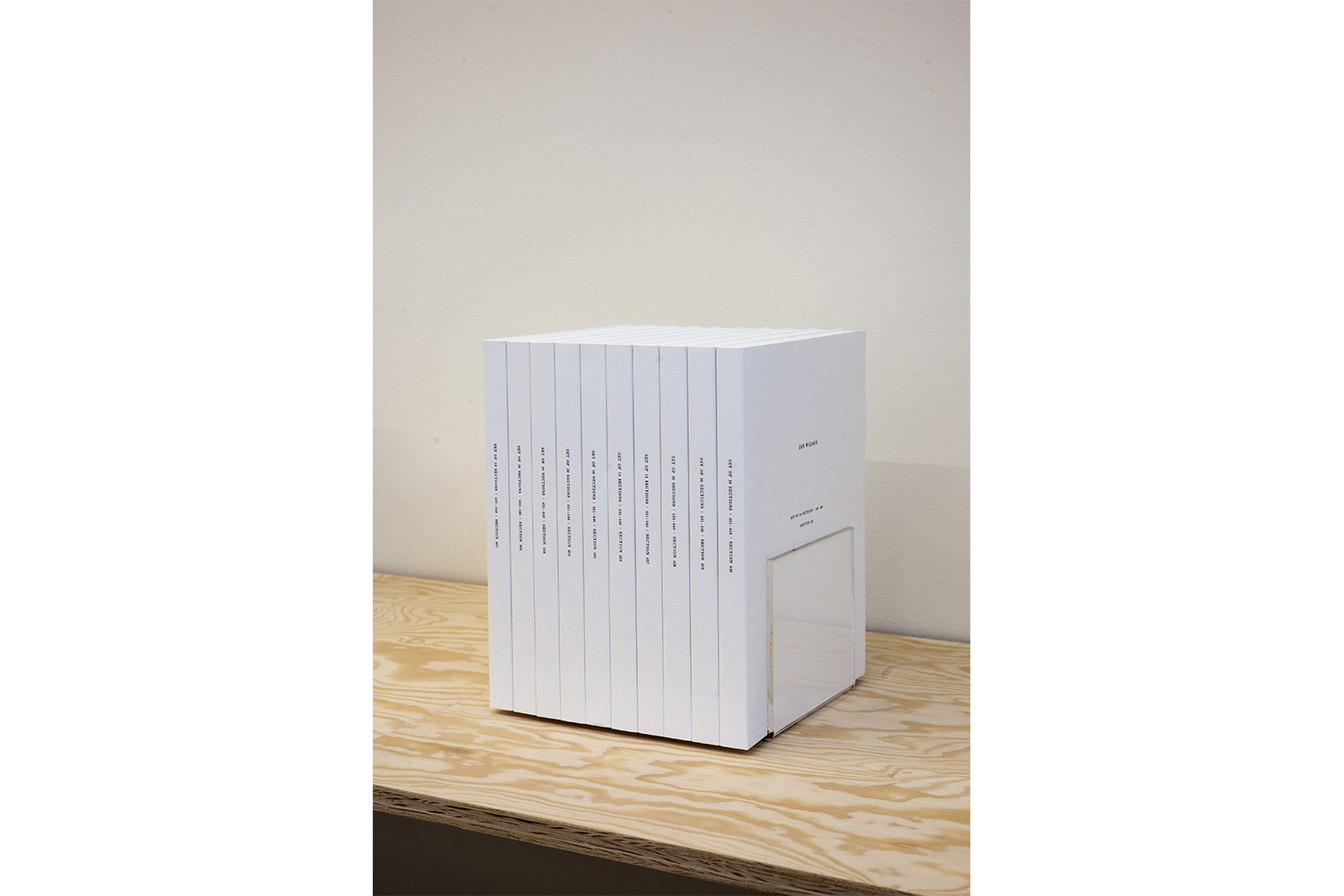

Apart from its vestiges in these certificates and a few rare publications (the “Section” series, from 1971 to 2014), Wilson’s work took the form of words that were spoken and exchanged, shared by the artist with one or more individuals. It was through this “interactive mental engagement”13 with the other participants in the discussion that the work manifested itself. It is thus a kind of artwork that exists in its own moment of encounter and experience, within a specific, delimited time, though it differs from the “realism” of Happenings or the scandalous, head-on approach of body art. One might say that, once every word has been uttered, the art vanishes and gives way to the artwork. On the other hand, a record of the work remains in the oral accounts of those who have taken part in the discussions. This cultivation of an oral paradigm, in both the experience and documentation of the work, is one of the most radical tools Wilson used to break out of the linear evolution of modernism, entering a circular time free of memory or progress.14

In this sense even Circle on the Floor (an unlimited edition that, while not mechanically produced, always remains the same) could be seen as foreshadowing the way that time, orality, and experience intersect in Wilson’s work. Its form suggests both a possible depiction of circular time that seems to predate his interest in Hindu philosophy — which the artist later explored more directly by entering an ashram in 1986 — and an action carried out within a span of time, however brief: the moment of making the circle, which is always new yet always the same. On the other hand, the circle drawn on the floor also evokes a meeting ground, a perimeter around which people can gather to talk. The themes of time and orality, of words that vanish like/with time, of art that takes place only in a given moment,15 already seem to be converging.

And so this circle could be seen as the starting point for a wave that would touch more than a few artists, all prompted by Wilson’s discursive practice to question the objecthood of art and its independence from time. One might begin with the generation that emerged in the early 1990s, especially in France, around the critical and curatorial work of Nicolas Bourriaud and Eric Troncy. Artists like Liam Gillick, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Rirkrit Tiravanija, and above all Philippe Parreno focused on the element of time within their artworks and exhibitions, in part as a response to the new technological world that was emerging with the spread of personal computers and the birth of the World Wide Web.16 These artists wanted their exhibitions to be a “space-time zone,” “a place where time was experienced ambiguously,”17 where works exist in a constant state of becoming. Parreno’s practice has been a perfect example of this. While in the last few years, the French artist has overcome his early elusiveness and begun to construct exhibitions that are monster-machines, devices that seem technologically unconstrained by human presence, one cannot help thinking of Wilson upon reading recent statements such as: “If an exhibition is not based on objects, it can be easily broadcasted. It can become an idea, and ideas can be spread and influence people.”18

The maieutic approach of Wilson’s “Discussions,” the possibility of turning the spoken word into a form of art, could surely be considered a precursor of the discursive turn that has spread through contemporary art since the early 2000s. The lecture-performances of choreographers like Xavier Le Roy (as early as 1999, with Product of Circumstances), artist-essayists like Seth Price, and artists like Benoît Maire and Falke Pisano, as well as the “situations” of artist-choreographers like Tino Sehgal, have a discursive, sometimes meta-linguistic aspect; but in addition, they exist above all, or even exclusively, during the artist’s encounter with an audience, in a dialogue that may be participatory and may exist only within that moment of experience, in a specific place and time. In this sense Tino Sehgal’s “constructed situations”19 take Wilson’s legacy even further, in at least two directions. On the one hand, there is the aspect of philosophical speculation in dialogue form, recurrently found above all in some of Sehgal’s early works: in This Is About (2003), an interpreter tells viewers about Sehgal’s artistic practice, while in This Objective of That Object (2004), interpreters keep repeating the phrase “The objective of this work is to become the object of a discussion,” then collapse, as if utterly drained, unless visitors take the hint and begin a conversation. On the other hand, Sehgal’s wish that the work never be documented through photographs seems to build on Wilson’s oeuvre: emphasizing the unique moment of encounter between work and viewers, the possibility of an experience that, like the “Discussions,” can be passed on only by word of mouth, through the accounts of those who took part in them.20

In short, the kind of art that is manifested only “live” in the context of an exhibition, however vast and even spectacular such shows have become, has a key precedent in Wilson’s discussions. If some artists — perhaps in response to the ease and pervasiveness of documentation through images in the digital era — are focusing more and more on the exhibition format rather than the artwork, on constructing an experience inseparable from a given “here and now,” they are indebted to Wilson for the idea of an artwork that exists solely as an encounter between individuals, avoiding all forms of technological mediation.