For Ian Hamilton Finlay, not only is our contemporary world a secular, materialist and fallen one from which ideal meaning has been banished, but also our perception of nature (as our sole tangible link to the extra-human and sacred) is now inescapably framed and informed by a welter of previous interpretation.

Most striking about the work of Ian Hamilton Finlay is the almost unbroken presence of language, of words and bits of signage that speak, elliptically, of half-hidden meanings. This language, always connotative, imagistic and succinct, has been made by Finlay to compellingly inhabit the space in which it might be situated and into which we, viewers-readers-visitors, are drawn. The space — be it a gallery room, the field of a printed page, or even a hillside garden — is itself, as a consequence, translated wholesale and quite wondrously into language’s (i.e., thought’s) own domain. If sufficiently mindful, we, for a spell, when encountering a Finlay work, are conveyed there too.

Summing this action with elegant pithiness is a 1989 Finlay Maquette in marble made for a circular “Classical” temple. The frieze of this temple-in-small carries a verbal pun — “Temple, n., a marble edifice, a veined edifice; the seat or summit of reason” — that conflates the sacred architecture consecrated to a god with a spot on the skull that is delicately transparent. “Reason” here, we realize, means not merely logic but rather the all-engendering, all-ordering “Logos” of ancient Greek philosophy; and Finlay’s little temple comes suddenly, through the addition of a phrase, to sturdily epitomize an unfathomably vast universe of human thought and spirituality. As implied in this Maquette, Finlay’s art is unusual for threading adeptly through all manner of discourses and mediums: philosophy, Classical mythology, history, poetry, visual art, nautical lore, warfare and revolution, and landscape design are variously given form in cards, books, prints, sculptures in stone, wood or bronze, neon signs, gallery installations and fully realized gardens. Yet the constant of language in Finlay’s work is the engine powering his art’s both sensorial piquancy and far-ranging allusiveness.

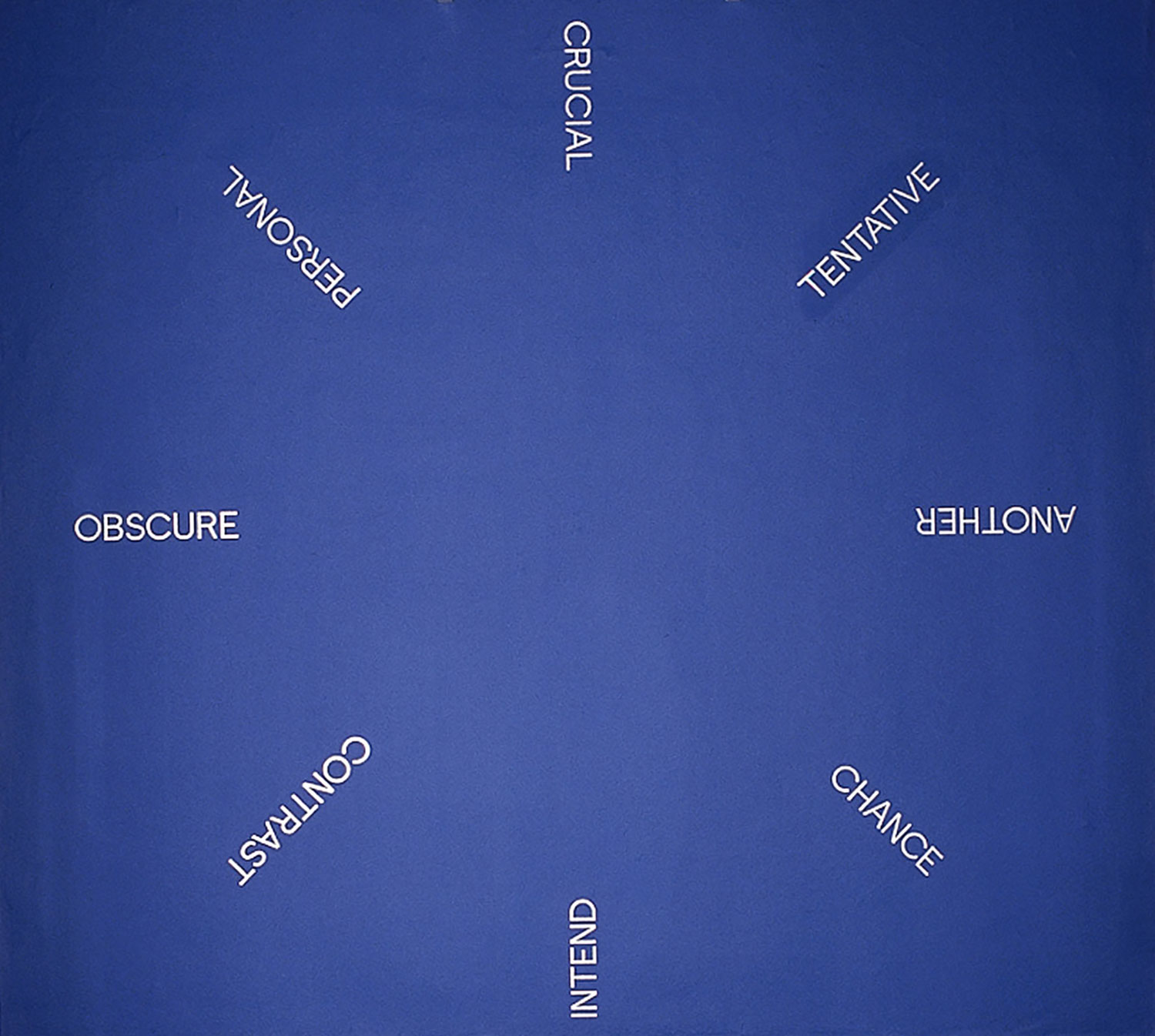

Finlay, by his own description, was first and foremost a poet. His practice, as a poet, was to give body and thus urgency to an array of ideas, perceptions and feelings that are not readily contained or communicated by words. Poetry’s time-honored instrument for snaring or embodying thoughts as fugitive as breath, as air, is imagery and above all metaphor. Metaphor, in an invariably adroit and arresting way, is the mainspring of all Finlay’s art. In every Finlay work, two or more seemingly incongruous terms are placed in direct relation, often a simple physical propinquity. These terms, in turn, can only be encompassed metaphorically (conceptually) and, through their enforced collision in thought, each is brought to radically redefine, or transform, the other.

Every Finlay work, as a metaphorical construction, thus also enacts a metamorphosis meant to spark cognition and spring open our power of envisioning. A beehive becomes a temple; a fishing boat becomes the fruit of a lemon aglow with the light of the ancient Mediterranean; a machine gun becomes an “Arcadian flute” as its air vents are translated into finger-stops; the pineapple of hospitality becomes a grenade (“granate”); a girl becomes a reed that becomes music that becomes air.

Finlay has explicitly invoked Ovid, the poet of metamorphosis, whom he defines as “the first poet of camouflage.” Camouflage is in Finlay’s universe a type of engaged or “armed” poetic language that conceals even as it gives hint of forces beyond human rendering or reining and of a god-like vitality that is cataclysmic as well as re-creative: nature as Nature, the forever unfathomable Other, which, in one of its Finlay guises, is the Sea. A Finlay metaphor may be as both concise and profound as the two-word and solemnly punning poem “WAVE / avé”; and it may travel in an instant from the humble or comfortingly familiar to the exalted and enigmatic — from, say, the “rose” of a garden watering can to the half-wild “rose” of fable and literary romance.

Finlay’s genius and wit, however, was to take metaphor quite literally into the world by means of inscription, or the grafting of language directly onto real objects and ultimately the landscape itself. This use of inscription evolved naturally from Finlay’s early work as a concrete poet. In the ’60s Finlay began to experiment tirelessly with the formalist properties — color, scale, composition, layout, typography — of the printed word and to shape a forceful, almost consistently beguiling visual shorthand by which verbal meaning might be inflected, unsettled, and immeasurably enlarged. Finlay found that the connotative dimension of his “poems,” his works, could be equivocated and breathtakingly expanded, even to the brink of articulation or the unknown, through the simplest of literal means. For example, a lovely “Concretist” folding card of 1974 consists only of the word “Schiff” (“ship” in German) set in a blue font that visually transmutes the “S” and double “ff”s into billowing sails and the word itself into an imaginary, antique galleon venturing into the uncharted geography of the white page. Is Finlay’s “Schiff” a kind of neat baroque fancy, or an emblem of the poet-artist’s own endeavor or possibly of the wayfaring human soul?

To treat words, letters, phrases or other signs as visual as well as signifying devices is to give them, automatically, a certain “object-ness” or resolute solidity; and most of Finlay’s works “read,” both in fact and in sense, as unassailable assertions. It is also, however, to situate these devices in a real space that, known through the senses, impinges on the viewer — a space suddenly, provocatively and almost uncannily made fraught with meaning. For Finlay, the concrete poem and, later, the inscription — each “a model of order, even if set in a space of doubt” — answered a moral imperative, actively re-affirming poetry’s (art’s) place and thus relevance in the world. As inscriptions, whether on paper or in stone, on a gallery wall or in a garden, Finlay’s metaphors — or rather the ideas his metaphors would convey — at once acquire a sensuous, emphatic, seemingly irresistible physicality and lay bare a polemical edge. Finlay’s famous garden Little Sparta, at Stonypath in southern Scotland, was so named to proclaim its creator’s embattled stance.

Set in the windswept Pentland Hills, the garden of Little Sparta, Finlay’s great work of over four decades’ making, is itself a protracted poetic inscription upon a once- barren upland. Finlay’s use of inscription in the landscape consciously harks back to the Neoclassical English garden of the 18th century and to a tradition of the garden as a place, in Finlay’s own words, “not [of] retreat” but of “attack,” a place intended to elicit serious or “noble” poetic, philosophic and even political thought. At every turn along Little Sparta’s paths or in its woods, language — now plaintively, now aggressively — waylays the visitor. Plaques and tablets, benches, bridges, planters, column bases or capitals, urns and more all carry words or other signage. This language, in relation to the objects upon which it is inscribed and the landscape in which it is positioned, functions in the end metaphorically to conjure up a radical space of the mind beyond sight or touch — a space stretching, in Finlay’s poetics, as far both as the Ocean, in all its possible meanings, and as Classicism’s mythical Golden Age. The remarkable inscription that is Little Sparta, in an action recapitulated by almost every Finlay work, moves through the concrete and literal in order to vividly — to palpably and vehemently — recapture the ideal. For a grove or a glade, Finlay asks us to read anew “Grove” or “Glade”; or for a tree, to see a wood nymph armored in bark; for a pond, to perceive an “exerptum” (excerpt) of the far-off Sea. In short, for Apollo, god of the creative faculties, to apprehend a militant distillation of all the arts in their potentially fine, complex mordancy. Inscription at Little Sparta thus mediates as a bridge between the familiar world of sensory phenomena and a fabricated and open-ended realm of pure reference. Little Sparta is garden as well as idea, also mediating quite literally between the cultivated and the wild. Mediation is a point of departure for Finlay, who transformed his garden into a sustained meditation upon the entangled relation between Culture and Nature: his art became a study of our culture’s shifting representations of Nature. Over time, Finlay gradually commuted the garden at Stonypath into the deeply reflective artwork that is Little Sparta.

Inscription, especially in stone, is commemorative by tradition: a lapidary record intended to safeguard its contents from oblivion or loss. A Finlay inscription taps this tradition and is an artifact of its maker’s respect and even affection for his varied subject matter. Most Finlay inscriptions combat an oblivion effected, however, not merely by the passage of time but also by what, far more critically, Finlay perceived as our modern culture’s materialism, secularism, utilitarianism, cynicism and vacancy. More pointedly, modern art, severed from faith and from a perception of the universe as vitally informed by meaning, has shrunk to an empty formalist exercise, to decorative irrelevance.

Like other Finlay installations, the garden of Little Sparta bristles with disconcerting images of warfare, revolution and out-sized violence. These images are forms of sublimity and terror in our corrupt age. Through such imagery Finlay sought to arm his art with an aura of perfect, or god-like, significance, immediacy and force. Nature, too, though addressed through a contemporary garden, is not merely a modern garden’s pleasaunce (or, for Finley, a “Cytherea”) but has been re-invoked, formidably at Little Sparta, in all its terrible, ancient, god-visited beauty. Nature is once again to be understood as an “Arcady,” a severe if enchanting pagan Eden.

One of Finlay’s “Definitions” spells out the distinction: “MILITARIA, n. aggressive hardware, the absence of which distinguishes Cytherea from Arcadia.” At Little Sparta and elsewhere, the visitor-viewer is impelled by the presence of militaria to re-conceive both Art and Nature as they were once apprehended in nature philosophy from the pre-Socratics to the Romantics: i.e., as boundlessly potent and potently present, as sacred.

Another Finlay “Definition” revises the concept of neoclassicism: “NEOCLASSICISM, n. a rearmament programme for Architecture and the Arts.” Ideal power, vitality and transparency of expression are attributes only in myth and, more particularly for Finlay’s art, the Classical myth of a Golden Age. All our latter-day neoclassicisms — which together mapped for Finlay the field of Western Culture as an ongoing efflorescence of Greek and Latin Classicism — are at best failed attempts to recover what Finlay, by another name, has called Classical “purity.” At worst, however, the history of neoclassicisms, the history of our culture, has been one of deadly perversion: a history in which Classical forms and imagery, cut loose from their original contexts yet still wrapped in associations of illimitable power, originality and ineluctability, have been appropriated time and again for brute temporal ends.

This history extends back to the Classical World itself (Imperial Rome) and has found its instance of possibly most egregious excess in 20th-century Nazism. Finlay’s “Neoclassicism” is a “programme” to redeem Classicism’s formal vocabulary and this vocabulary’s original but now long- buried meaning from historical debasement. The neoclassical devices — e.g., lapidary inscription, the temple form, columns or column elements, sundials as memento mori and obelisks (these last taken from Renaissance and 18th-century classicisms) — that Finlay has borrowed for his works are cunningly restored to their first source in nature. In a garden this restoration is literal; it has also been made to occur through the superimposition of naturalist imagery (birds, wildflowers, leaves and woods, streams, the heavens, the ocean). Nature, both as the raw universe of natural phenomena and as the haunt of the divine — of the untrammeled human imagination — becomes once again the first and ultimate referent.

Finlay’s inscriptions — elliptical, fragmentary, allusive — communicate a very modern awareness of language’s instability and imprecision while looking back to Classical inscription as a not only memorializing but also epigrammatic device. A Finlay inscription, for all its assertive, sensuous presence, is semantically elusive as well as elegiac. At the core of every Finlay work, behind or within its suggestive “camouflage” of words and imagery, is to be found, finally, absence. The Golden Age of Classical myth is a vanished dream now only to be summoned through artistic conventions or figures of speech. All of our envisioning and representations of Nature, even so-called empirical ones, remain but man-made, or cultural, constructs.

Our vision, as one Little Sparta work quietly insinuates, is deeply “shadowed” — at once occluded and richly inflected — by earlier language, above all Latin (the conduit from Classical to modern): “Cogitatio Sub Umbra Latinae Celata.” We come belatedly to a nature thickly tracked- or written-over, digested, and de-naturalized. Finlay, through quotation, citation and incisive excerpting, has set a vast array of these prior re-definitions of Nature — from textual remnants of pre-Socratic philosophy to the nature imagery of the French Revolution to the poetically evocative nomenclature of Scottish fishing boats — into the real landscape of Little Sparta and elsewhere in order to reinvent and revitalize them. Broken vestiges of now remote discourses, Finlay’s inscriptions are capable, however, only of indicating Nature and the Ideal metaphorically, or indirectly, and stand at last as epitaphs to their loss. A Finlay work, even at its most truculently militant or invitingly tender, survives within elegy and twilight. Like all great lyric poetry post Virgil, Finlay’s art is haunted — has been chafed into being — by a mortal sense of diminution, absence, uncertainty, impermanence, imprecision and frailness.

Presence vs. absence, concrete vs. Ideal, near vs. far, intimacy vs. grandeur, delicacy vs. power, now vs. a mythic then, shade vs. light, ceaseless change vs. perfect form, garden vs. Ocean, Culture vs. Nature, these are among the intertwined pairs of opposites upon which the meaning of Finlay’s art hinges. As a metaphoric recasting, each pair is a reflection of the schism in language between literal and figurative.

Finlay understood instinctively that meaning resides not so much in the said as in the unsaid: in the gaps between words, in the conceptual space between a metaphor’s terms, and in the now inescapable disparity between words or symbols and their ideally intended sense, a disparity that measures our remove from divinely flawless expression. Terms, words, inscriptions are in themselves but inert, narrow pointers —fragmentary traces — of once- living, protean thought and feeling. “how blue? / how sad? / how small? / how white? / how far?” laments, in searching doubt, an early Finlay concrete poem which then defiantly concludes: “how blue! / how far! / how sad! / how small! / how white!”

Finlay’s art finely mines the notion of language as a field of representation in which every word, sign, mark, letter or symbol, no matter how small or succinct, stands both for itself and for something other and absent and endlessly fugitive. (Naming, a type of re-defining of which Finlay has made express use, is itself a metaphoric act at once invoking and irreparably distancing the thing named.) Within the “distance,” or difference, between each concrete fragment of language and its wished-for referent or between each metaphor’s terms, Finlay has located a dynamic space of connotative possibility. This space, a carefully recaptured arena for imagination’s play, has been made by Finlay as open, fluent, unanchored and far-stretching — yet still vivid — as possible, short of its slipping into incoherence. (Another Finlay “Definition” suggests this space is a maze to be navigated by supple thought, or concepts: “CONCEPT, n. the thread of Ariadne.”) A Finlay work, which is in essence a Finlay metaphor, is paradoxically both riddling — provocatively enigmatic — and sharply urgent because so utterly pared down (“laconic”), so very free of qualifiers. Half-cloaked in mystery yet always stubbornly speaking, Finlay’s works are meant to detain us, and it is finally we, the viewers-visitors-readers, who are goaded to bring them, through strongly imaginative reinterpreting, newly and ever again newly to life.