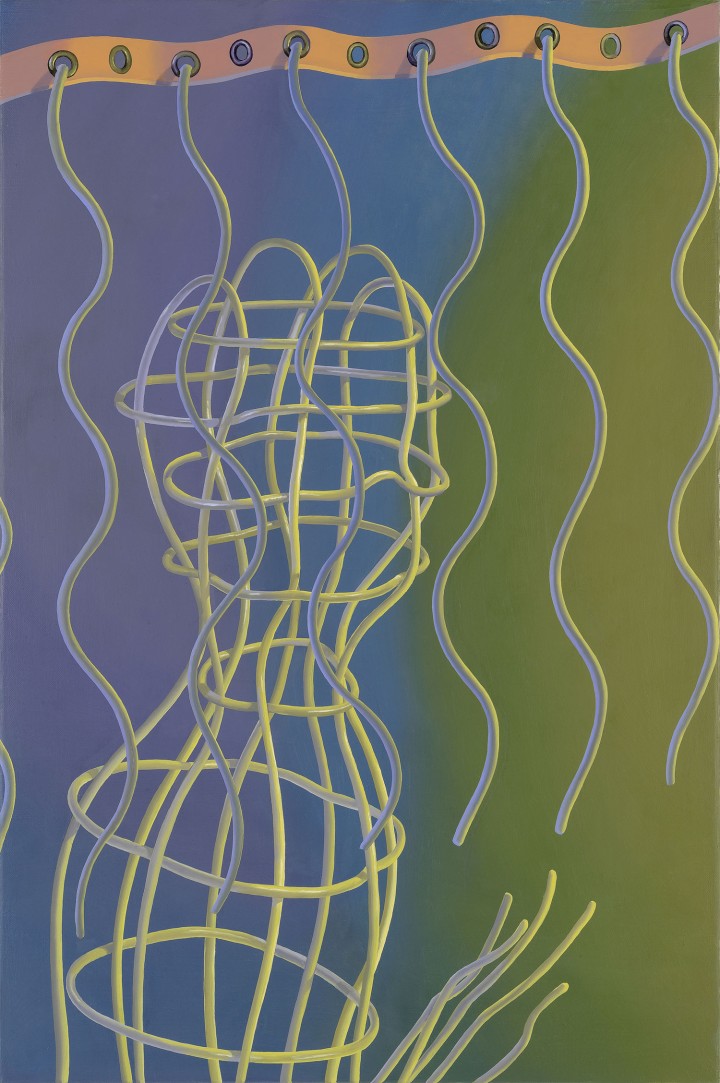

The figures in the paintings of Sascha Braunig (b. 1983, Canada; lives in Portland, ME) and Avery K. Singer (b. 1987, USA; lives in New York) are both strange and elusive: they torque in vectorized versions of human bodies, in the case of Singer, and emerge from kaleidoscopic backdrops or simply hang like shimmering nets, as if they are more border than body, in the work of Braunig. And yet, these forms are also unsettlingly familiar: in a time when our personae are increasingly mediated and detached from our skin and flesh, their surging energy and porousness feels real. Here, Lauren Cornell discuss with Braunig and Singer their processes and motivations, and how they relate their works to the politic of painting and life today.

Lauren Cornell: All of your works bring figures to life: be they busts dissolving into vibrant color fields, as in your paintings, Sascha; or a couple in the throes of a wild embrace in yours, Avery. Where do these figures come from? What are your references, if any?

Sascha Braunig: The figures are formally kind of self-generating, arising from antecedents in my own work and in others. However, their DNA is made up of lots of things. Back in college, I was making Frankenstein-like paintings assembled from the commercially produced gleams and pores of fashion magazines. The lighting and look is also influenced by B movies, art film and video, and still life painting. Over the past two or three years, surfaces have become smoother and more stylized; this is a conscious move towards an abstract openness, but also results from using casual clay and thermoplastic models as visual clues, rather than painstakingly observing detailed mannequins.

Though these references may not be explicit to the viewer, in my mind some of these figures are descended from unstable, unpredictable characters in fiction and culture, like Charlotte Brontë’s madwoman Bertha Mason, and her ghostly ancestor, Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca. Artists who are better known as artists’ muses, like Dora Maar and Unica Zürn, come back to haunt my images. Females who, for political or personal necessity, have historically taken control of their own representation, like Madame de Pompadour or the Countess of Castiglione, are finding their way in too.

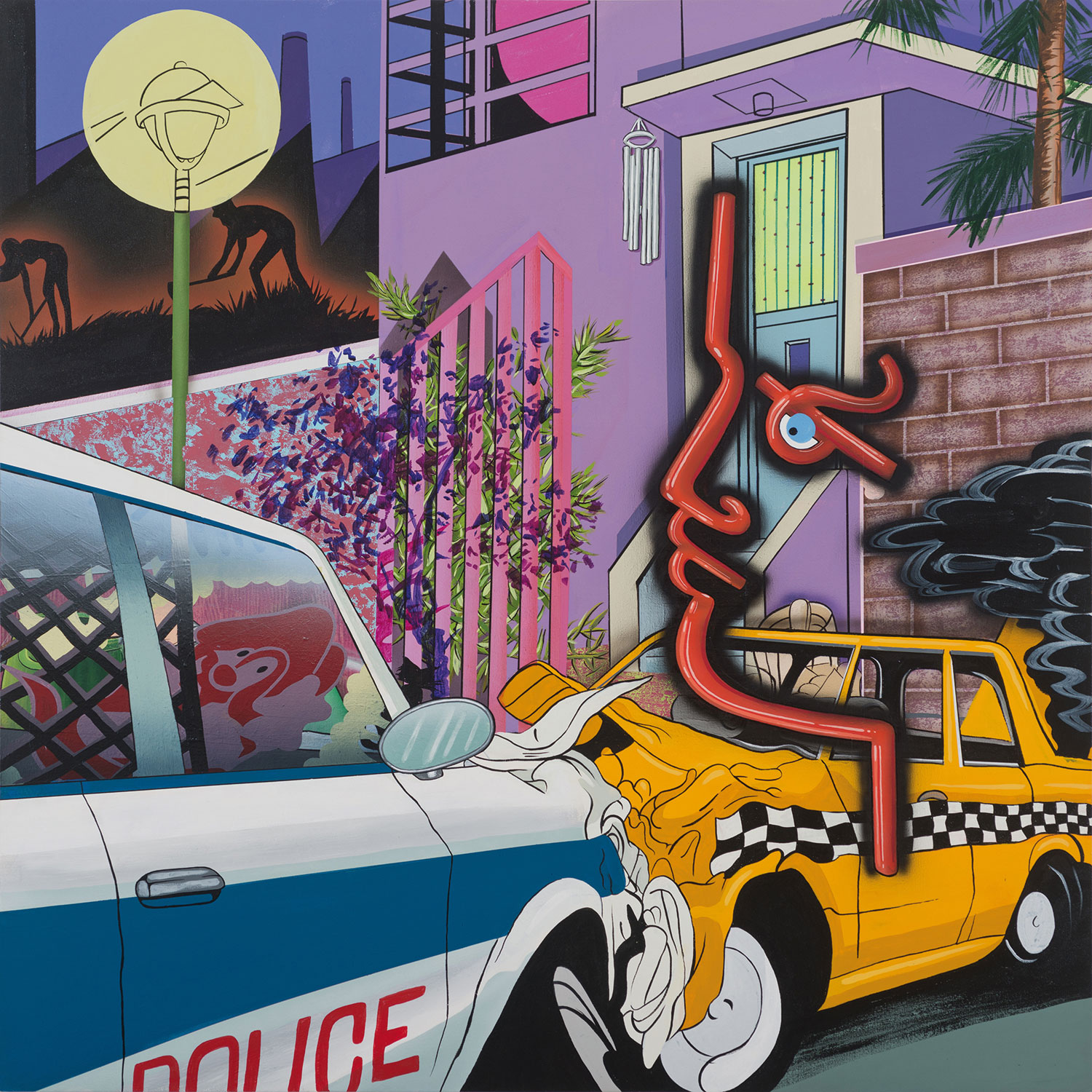

Avery K. Singer: To take a step back: my position as an artist begins with a certain kind of skeptical perspective on how my own artistic project reflects on agency and meaning within modern life, or what we would call capitalism. Thinking of and isolating ways in which we are in a fixed position as bourgeois individuals, and then filtering this through representational painting that has a kind of finite language, so the form of the painting is a metaphor for its own examination of cultural conditions. I took things that I saw as being out of fashion or not in the purview of current market tastes; for me this was narrative, figurative painting, dumbed-down computer aesthetics, colorless painting and airbrush — a hobbyist medium — to highlight the surrounding or essential conditions in which art and meaning get produced.

I realized that I had not seen paintings that employ 3-D modeling software as a means for image production, so I began to experiment with that. The figures are abbreviated human forms that are meant to convey the process of banalization that occurs through the consumption of our lives through capitalism, and how we might languish or excel in that. There was also this question of How do I break painting out of its masculine spell? What would that look like? For me, that seemed to be most potent by eliminating the physical appearance of the brush stroke but retaining the aura of mark-making.

LC: Sascha, with a myriad of representations of womanhood in your painting — sometimes even haunting your painting, as you say — I wonder if breaking that insistent masculine spell is on your mind, as well?

SB: I think that in many ways the spell has already been broken by generations of excellent female and queer artists, and artists who are simply interested in fraying the mythic origins of what Linda Nochlin terms “phallic greatness.” That being said, to be a figurative painter (and I identify as such) is to be inextricably tied to those origins, to a long Western history of avant-garde innovation being enacted on the clay of female bodies. As a female, it’s impossible not to want to respond to that history anew, for myself — the spell must be broken over and over! But my response is not a direct-line critique. I feel implicated and involved, and so my response is rather to perform my position as a “creator” of images in a critical way.

LC: From working with you previously, I know that you are both constantly driving towards experimentation in form, subject matter and, sometimes, scale. Avery, you’re about to open a totally immersive painted environment as part of Art | Basel Statements. What’s at stake in the scale of a work for each of you?

AS: I saw Fritz Glarner’s Rockefeller Dining Room (1963–64) in Zurich and the grisaille trompe l’oeil hallways in the Vatican within the past year, and these spaces just sort of rocked my world in a way I can’t describe. Despite my claims of being interested in innovative technological forms, what I’m doing has obvious antecedents that go back 500 to 600 years. I also want to make clear that I do make small paintings, but they tend to stay in my studio so I can continue to evaluate them over time.

SB: At this point, my work is not about immersing the viewer through large scale. I’m interested in evoking aspects of the experience of viewing traditional portrait painting — particularly the closeness of the encounter. You must approach the painting’s surface and see its flaws or its jewel-like precision. It adheres to illusion enough for you to feel a human presence, but sometimes that illusion collapses, for whatever reason — the artist’s skill falters, you are distracted by the frame. You recognize yourself. Maybe you forget yourself.

LC: Avery, you begin by mapping out your works in SketchUp and then translating these virtual models to canvas. As you say, painters have been projecting onto canvas for centuries, and thus the technique is not new, but the use of 3-D models is, and I believe it lends your works a unique sense of depth, as if the canvases are film stills or jpegs taken from a virtual environment.

Sascha, your works have a distinct tangibility: it seems as if your figures could leap off the canvas and, in many cases, they do leak or seep out of their own boundaries. You’ve also recently extended your practice by presenting one of your models — for the painting Chur (2014) — as a sculptural bust. Could you both discuss the role of the model or modeling in your work in both a practical sense — Do you use them to map out your compositions, and if so, how? — and also conceptually — Do you see your works as models of states of being?

AS: Art making is the question of “What do you find when you interpret?” I utilize computer modeling as a means to set up a kind of digital still life. I take the basic information that a selected still from each model gives me as a point of departure. I had begun a body of work in 2010 using Photoshop to produce sketches which I later based graphite drawings on. I saw after about ten drawings that it wasn’t an interesting path to take — I had seen these images and this approach to art making in many places prior. Instead of treating computer graphics as a flattening tool, I thought of using them as an illusory one, as a potential way to generate an unfamiliar visual reality.

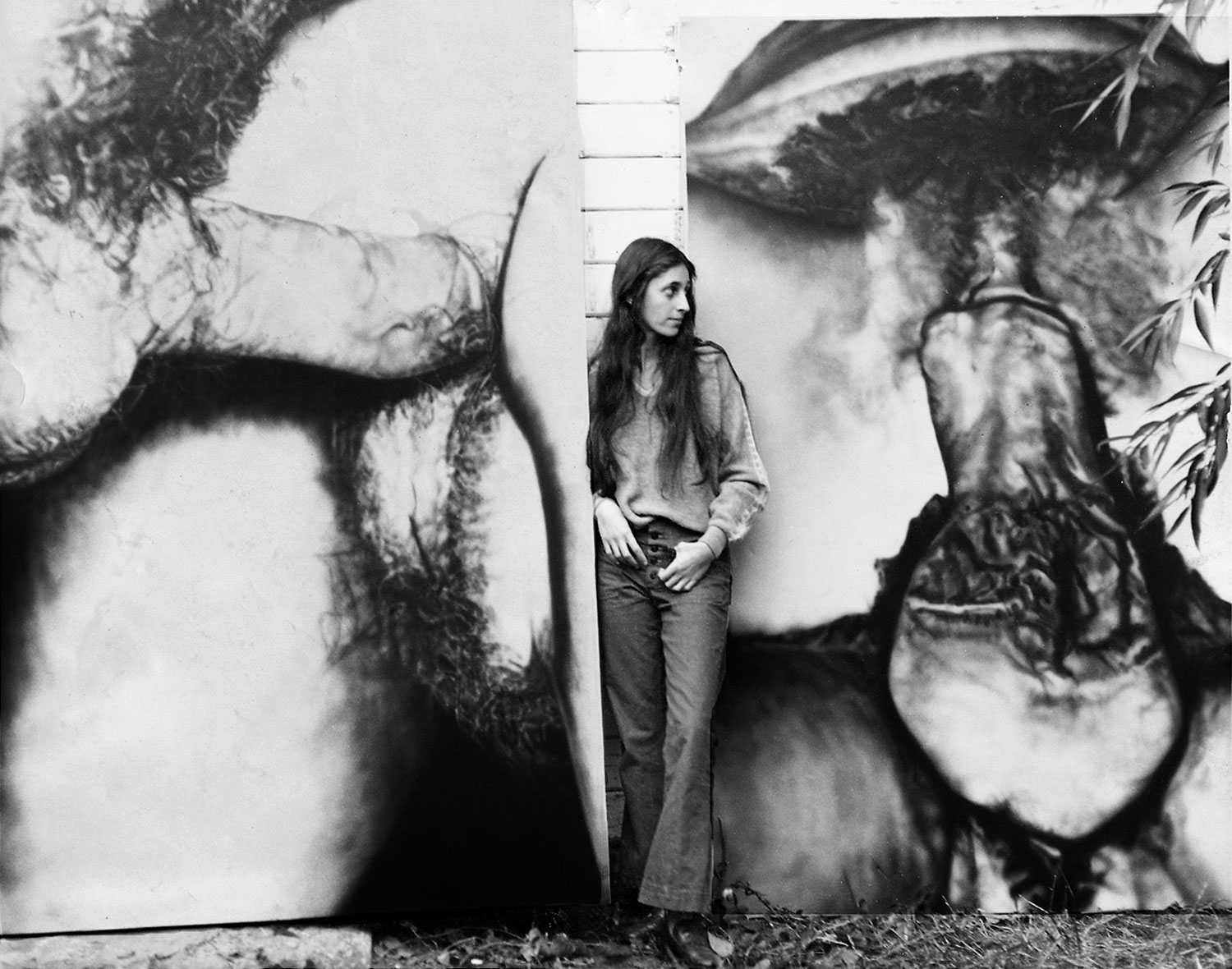

SB: Working from a model importantly creates a tangible dimension to the painting, because I’m observing real light and shadow — though this effect is no less strong in Avery’s work, where the light source is determined in a program; really these methods are different means to a similar end. At the start of what I think of as my current project, around 2008, I was making quite elaborate props using plaster or latex life casts, wigs and so on. I really felt like I was “playing with dead things,” to borrow the title of Mike Kelley’s essay. It felt slightly taboo, certainly an archaic move, to be painting from these props, a step away from someone like Cindy Sherman’s frank presentation of the things themselves. I felt like I was inhabiting a forbidden zone of the modern male grotesque, the zone of a Hans Bellmer or Oskar Kokoschka, but defining the perimeter myself. But to further complicate things, while I am the director of these works, I identify just as much with the paintings’ subjects, who would traditionally have occupied the role of the artist’s model. The figures are models of myself, sometimes literally, models for a female fiction. Among the ways I’m thinking of them now is as fictional descendants of artists’ muses who have become hypertrophied or attenuated, but nevertheless are defining their own relationship to the controlling boundary of the pictorial frame.

LC: Your works have both been spoken about in relation to the digital, perhaps because your figures have the feeling of avatars or virtual identities, as if they are skimmed off our bodies in order to give shape to the incorporeal: unconscious feelings, confining behaviors, expressions of liberation — sexual or mental. I would suggest your works respond less to digital media, i.e. tools, and more to the contemporary mediation of the self, where persona and socialization can be freed from the body. How do you think through this association?

SB: Lauren, talking with you over the past year has brought this topic to the forefront of my mind. I’ve always thought of the skins and layers over figures in my work as being ambiguously porous. They act as a decorative barrier over a core being, but are sometimes becoming shredded or perforated. To what forces are they porous, though? What do they need protection from, or what are they welcoming into those gaps? Well, interaction and the onlooker’s gaze, perhaps. It’s an understatement to say that a reliance upon the digital collective, a surrender to an infinite field, has strongly supplemented our social interactions in recent years. So my paintings, which in one way are about the subject’s interaction with its environment, have to reflect this change. Recently, yes, I have pushed figures to extremes of dissolution, where they are just a mesh or markers of volume in air. These are single figures, but they are often embedded in or dissolving into their matching environment. It’s unclear who is acting on whom. Is the figure reflecting its ground, or vice versa?

AS: I think I found a digital “look” as an effective attempt in my semi-narrative scenes to satirize nostalgia for bohemian tropes. The tropes of the artist’s career are essentially nostalgic, commercially constructed fantasies. SketchUp reflects a late capitalist assumption that connectivity, communication and especially production within these spheres are themselves economic assets.

LC: These concepts of anti-nostalgia and the digital collective underpin, I think, how much your works capture aspects of our current lives, or, as Avery says, “the surrounding or essential conditions in which art and meaning gets produced.” This — not just figuration, but this approach — is arguably different than the one ascribed to abstract paintings, which can still slip, in their interpretations, outside language, even outside time. Do you find that you’re actively trying to situate your works in our moment, in conversations around painting and visual culture now?

SB: I’m not trying to situate the work as being particularly “current,” but I do take a view similar to Avery’s materialist view of art history, wherein art is made by individuals but also by the conditions surrounding its making, whether those be very stable or very unstable. Surreal — or hyperreal, if you like — imagery in sci-fi literature and in image culture has been preparing us for years for the developing conditions of the digital collective, and by and large, we embrace this new way of being. Digital networks are literally suffused through the air — how can art not reflect and absorb them?

AS: The understanding of issues surrounding abstract painting seems so reliant on specific, well-defined 20th-century historical tracks, and often about how we can romantically inhabit their mystical quarters. Not that I’m trying to defend representational painting — I think these categories are wholly inadequate to address the entire scope of concerns germane to contemporary art production. I’m not really interested in having my work “look back” romantically, nostalgically. I find it weird to try to be and behave like you would imagine someone fifty or more years ago. To answer your question, I guess, in a way, yes: I’m trying to look forward from my own vantage point, because that seems like the most challenging and complex thing to do.