The most popular song of 2019/2020, “Dance Monkey,” is about mimicry, repetition, loops, and uncontrolled movement:

Move for me, move for me, move for me, ayy-ayy-ayy

and when you’re done I’ll make you do it all again […]

Just like a monkey I’ve been dancin’ my whole life

But you just beg to see me dance just one more time.1

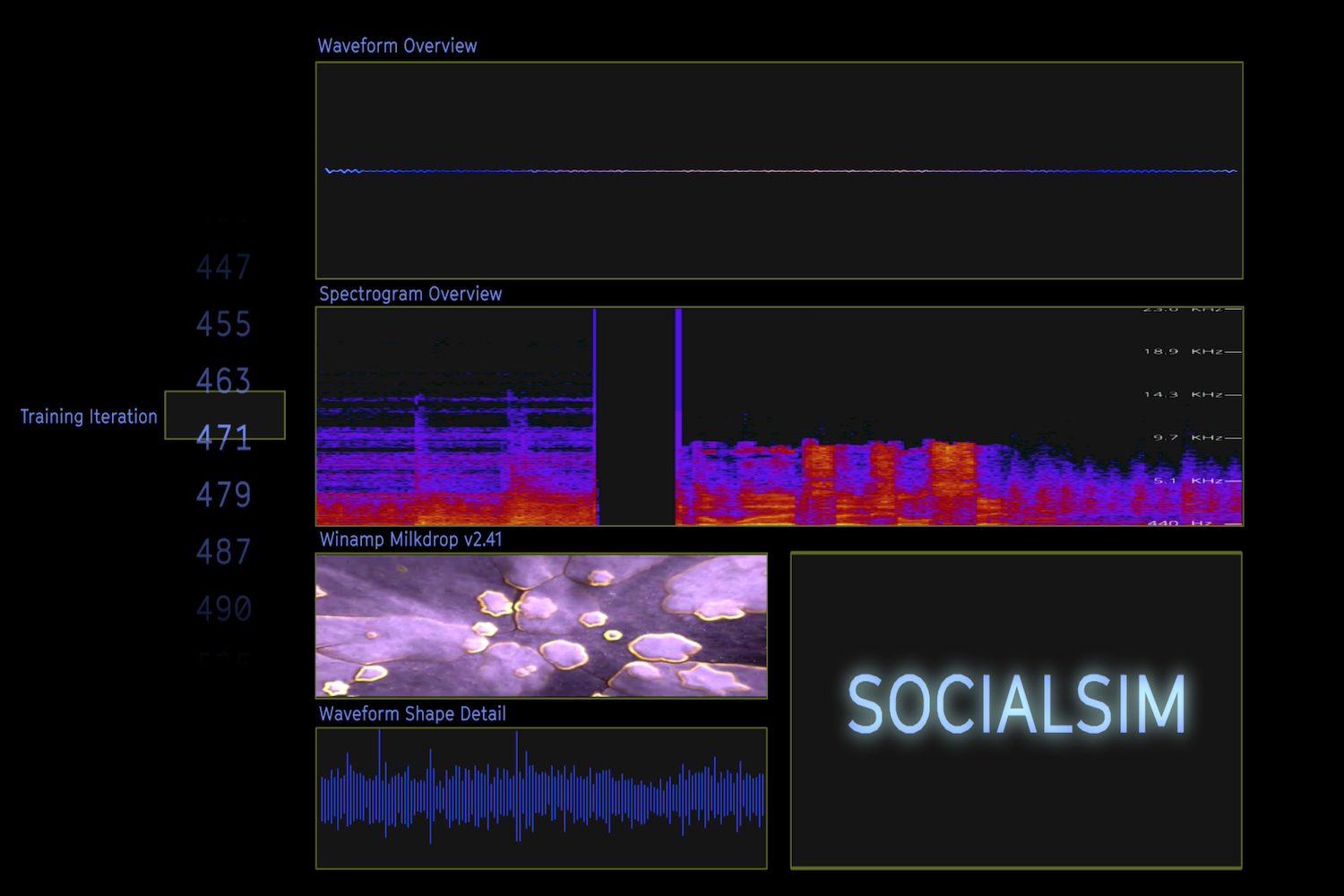

Near the end of Hito Steyerl’s latest video work, SocialSim (2020), a white male cop, foreshadowed by countless computer-generated avatars, states that he is “basically working for [his] own elimination.” This simultaneously expresses a utopian fantasy — if only cops would heed protesters’ chants and “quit their jobs” — and the mundane but disastrous knowledge that we are all basically working for our own elimination. The cop’s scanned avatar is better than he is. People cannot tell the difference, and the CGI version is cheaper, easier to produce, and easier to control.

SocialSim is a dense commentary on the frenetic state of media consumption, the complicity of art’s privileged internationalism in the policing of national borders and gross income disparities, and the ways that machine learning interprets, misinterprets, and ultimately reproduces an incoherent but still potent version of the authoritarianism that underwrites the whole enterprise.

It is a surprisingly pleasurable index of the past year — one that combines an astute commentary on bleak realities with a bright, playful, dance-worthy aesthetic. But this, of course, is itself a comment on the forms of our own algorithmic undoing: the disaster (all of us replaced by algorithms) disguised as utopia (cops eliminating themselves through the use of contemporary media).

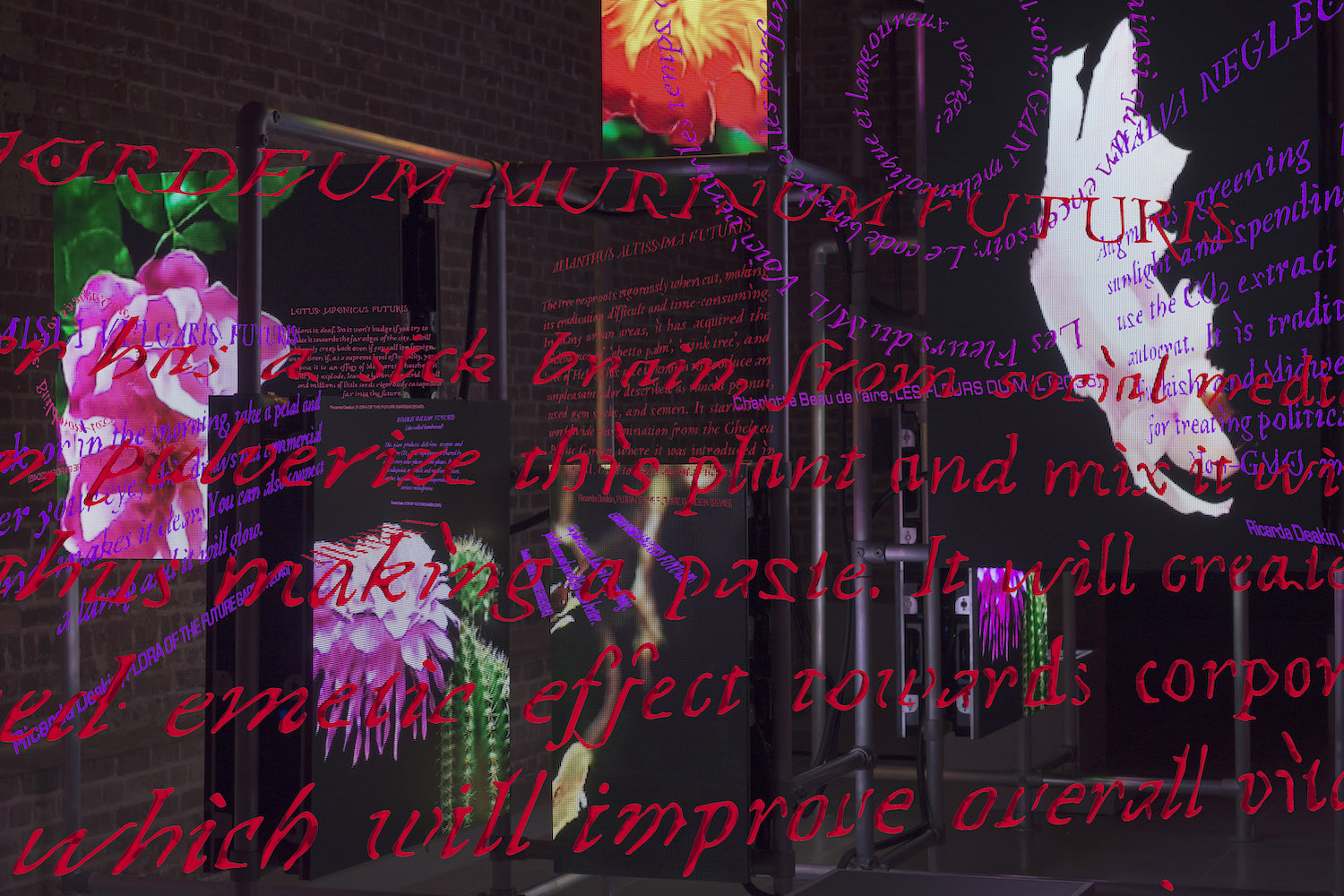

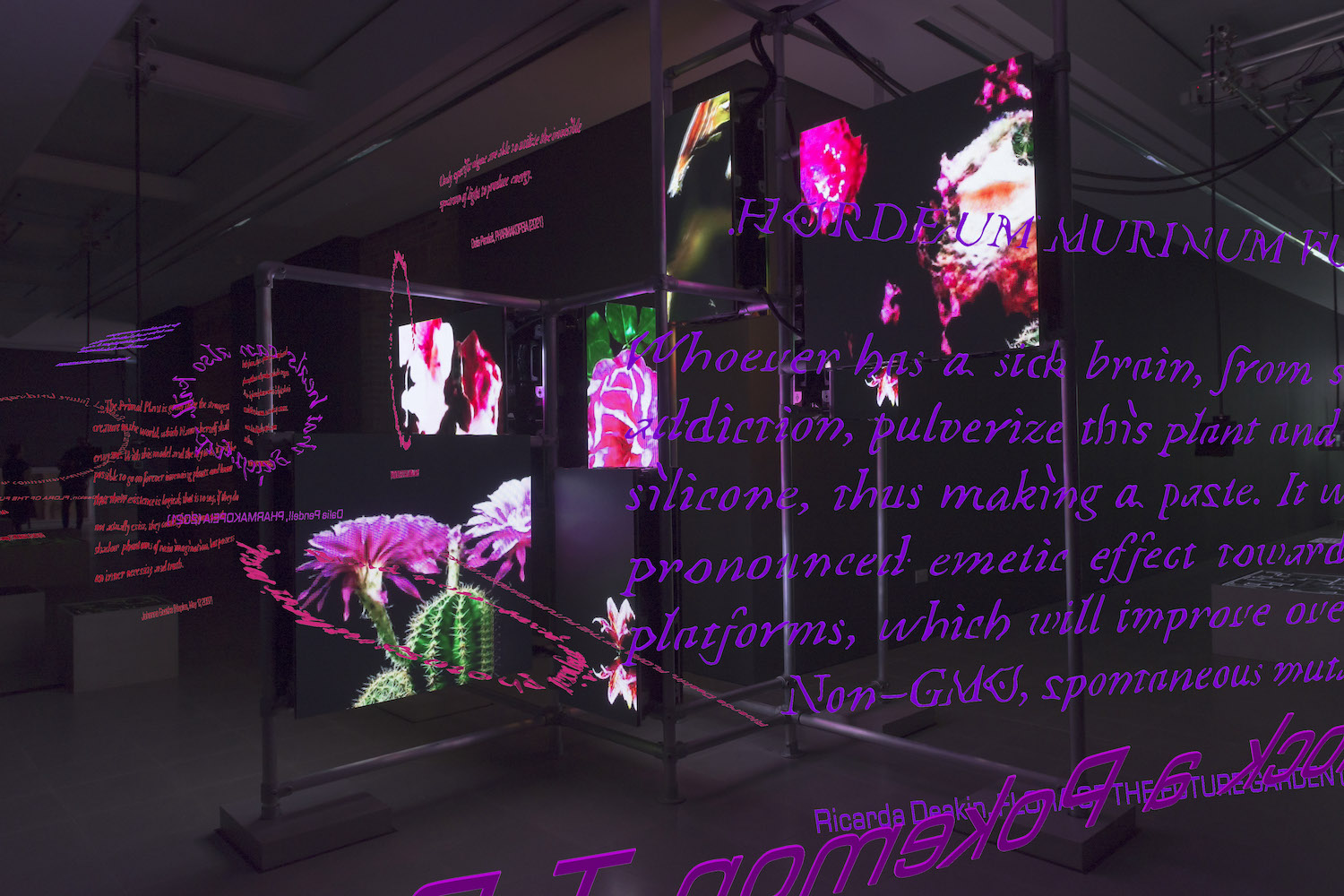

Prediction “science” is at the core of the artist’s latest work, along with machine learning, technology and law, power relations, intervallic space, and planetary concerns that span from communication to environmental realism. The exhibition “I Will Survive,” which premiered at Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen and is supposed to open at Centre Pompidou in February 2021, brings together work that collectively offers a comprehensive commentary on global power relations that resists summary and thus, appropriately, offers us no single, usable, or easily digestible analysis or answer.2

What is clear, though, is Steyerl’s interest in the relationship between machine learning, authoritarianism, and prediction.

The use of predictive technologies and networked surveillance for contact tracing during the COVID-19 pandemic realized what Steyerl calls “digital stupidity.”

It is a playful phrase, but its consequences can be dire: the algorithms have been known to misidentify individuals and quarantine the wrong person. Forced quarantine means removal from society (from family, from employment, from networks of care). Furthermore, once in place, the technology used for contract tracing can be (and has already been) used for more nefarious purposes, such as locating and kettling protesters.

The “science” of prediction is explicitly taken up in This is the Future (2019), previously shown at the last Venice Biennale, in which the protagonist, Heja, makes probability-based predictions and observes that “as the future becomes predictable, the present is much less so.” Statistics — which are, by design, meant to locate the common and ignore the particular — often provide information for predictions. Thus the future is prescribed by a quantified version of the past. Standard deviations are likely to be excluded because they make future predictions based on past behaviors less conclusive. In other words, the future, in order to be predictable, must conform to the past. What presents as progress is actually a form of stagnation disguised in the loop.

The possible range of mistakes coming from digital stupidity, predictions, disruptions, and “creative destruction” are represented in comical moments in How Not to Be Seen (2013), Hell Yeah We Fuck Die (2016), Robots Today (2016), This is the Future (2019), and in real life as well.3 In an interview, Steyerl discusses her experience of a digital mistake from a 2017 BBC news report in which the opening looped clip got scrambled and turned the “breaking news” into “broken news.” This momentary mistake, conjured by the automation of the news, presents a key potential. A realm of nonbinary possibilities stemming from this observation connects to the politics of the loop. Mainstream media .4 accommodates this more easily: once the loop is exposed, it can be digested back into the system or it may leap out of its constituting logic to create a multitude of possibilities opening onto a commons.

There are moments when we are able to exploit the stupidity of the machine that normally runs our lives; when we recognize the immense potential of the glitch; the moment we encounter the feedback loop, the intervallic space.

These are moments that can be easily absorbed into the capitalist logic of creative destruction. At the same time, it is an open-ended moment of production in which things phase in and out of syncopation and the loop is supplanted by multitudes.5

What becomes visible from this sketchy, wobbly aesthetic is an economy of care and solidarity, wherein images move and circulate out of love rather than control, power, or profit.

The Ride Never Ends

Steyerl is a researcher of these systems and movements. She traces “objects” like shifting neurons in a closed system. She traces the ways they move, encounter, contaminate, shape, become, and disseminate — how they evolve and conjure.

Like a cartographer of unknown machines, she maps a system by tracing those objects and their sources of movement and dynamism.

Those “objects” can be considered as the poor image, the poor piece of information, and the poor sound. What follows is an interrogation of the way they operate; what generates and enforces their differing movements; and how they exert gravity in a closed media circuit.

The poor image, described by the artist in a 2009 text of the same title, evolves along with media. In opposition to the sharp, glossy image of a simulation, CGI, or digital reenactment of an event, the poor, low res, easily transferrable image suggests a subjective, and therefore potentially politicized, understanding of an event. This capacity for politicization is not simply a result of its capacities for distribution and dissemination, but is integral to the way that it performs subjectivity.

In an era when forensic aesthetics are largely dominant, the “truth” is constructed by way of an aesthetics of science, abstracted graphs, coded presentations, and PowerPoint decks that stand alongside experience and offer an evidentiary version of the truth.6

This imagery looks glamorous, clear, cohesive, and lacking in contradiction. Conversely, the poor image is identified with real human activity, like political demonstrations. It is central to uprisings and revolutions: video footage generated by participants during the Arab Spring, Hong Kong’s recent pro-democracy movement, Black Lives Matter in the United States, and elsewhere. This version of the poor image is one of love and mutual support. It thus circulates via networks of solidarity that are politically challenging. The poor image often appears sketchy, sloppy, but it is real and is derived from the desire to support — to help and nurture.

The poor image is antithetical, in this sense, to the poor piece of information, and the latter’s aesthetic form of mainstream media that enables the depiction of white supremacist terrorists as somehow equivalent to Black Lives Matter activists — a form that co-opts all movements of or for difference into the movement of the loop. Which is to say the false movement of the status quo; the non-movement of endless political “repetition.”

Here the poor piece of information is key. The racialized English term “riot” is exemplary of the violent consequences of the unhinged, slippery signifiers of mainstream media. The term “riot” has been taken up and interrogated or reappropriated by many Black scholars and activists, including Gwendoyn Brooks, Martin Luther King Jr., W. E. B. Du Bois, M. NourbeSe Philip, Young Thug, and Cheryl D. Hicks. The word, in the mouth of mainstream media, signifies Blackness and attaches Blackness to irrational, violent destruction. The word “riot” has been weaponized throughout American history to remove African Americans from the very idea of democratic process and participation. Its use, as opposed to the word “protest,” has allowed for wanton acts of violence against demonstrators.

The poor piece of information also has another kind gravity, and gravitas, that Steyerl eloquently traces in SocialSim. The poor piece of information multiplies into an infodemic: the video shows how infrastructure and velocity are brought together by an invisible algorithmic hand to create an infodemic that, in the words of the director of the World Health Organization, “spreads faster and more easily than this virus.”7

The video Mission Accomplished: Belanciege takes on the question of infodemics and fake news directly to show that, like all feedback loops and processes of machine learning through repetition, once this process kicks in, it changes the structure of the system. As we learn in Belanciege, there are conscious strategies for creating aesthetic and consumer desire. Three times, explains Steyerl in Belanciege, is enough to align a narrative with a thing.

The “magic” of capitalist digestion and technological loops casts its spell — it widens the circle so that terrorists are incorporated in the interior ring while the exterior remains intact, protecting the freedoms of “ALL” Americans. The ever-expanding Mobius strip is designed to generate an abundance of disinformation, fostered by compulsion loops (that often includes hate speech and conspiracy theories), to discredit, undermine, or reposition truthful accounts. It expands the loop to create more signs: three iterations combined with proper media positioning are enough to make terrorists and activists the same, precluding any possible future resistance.

When we consider how the poor piece of information’s movement sketches a place of discourse we see that this politics of the loop is bound to diminish the space we occupy — like the kettling of protesters by police, which restricts the movement of political change in real space.

Gravitation here is based on a different logic that has been thoroughly naturalized: profit making.<href=”#_edn1″ name=”_ednref”>8. Steyerl brilliantly shows in Belanciege the architecture of the system of privatization — a spatially stretched, closed spiral that can be seen as a plateau of consumption on one end and reveals a layered, hierarchical, abusive structure from another perspective. The question that is posed by Steyerl — the question that must be posed — is how to open this closed system.

Love is Gravity | Sound Travels

The poor sound is the most complex object of the three.

Steyerl isolates sounds and sends them throughout her video works into the digital sphere. The sound of Broken Windows travels to SocialSim, while in it the sound of the word “socialism” is broken down, abstracted, and reconfigured as “social abstractions.” Kurdish music from Robots Now resonates in fragments of This is the Future, which in turn remixes the artist’s voice alongside other fragments of Kurdish music, together with re-soundings by Kojey Radical and others.9

In his masterful analysis of diasporic Black sounds, Louis Chude-Sokei suggests that the meaning of “sound” in Jamaican English contains an entanglement of meanings operating simultaneously, coming from different Black diasporic geographies.10 “Sound,” in Jamaican English, includes the notion of a sound system. Thus, sound means “process, community, strategy, and a product.”11 Sound requires a community of producers and a community of listeners. In this vein, he proposes that sound systems in Black diasporas, with their extended diversity, have functioned as critical spaces that provide alternative symbols and a spiritual sensibility that was missing from other modes of identity production and group construction such as nationalism.12 Unlike the technological machine that disseminates remixed sounds, here the “system” has to do with the meaning of culture as a way of listening.

Listening is also a form of solidarity, of love, and an important driver of an economy of care. Unlike hearing in general, where sound simply reaches an ear, listening is intentional.

In contrast to various sound types, Chude-Sokei treats the remix as “the most blatant form of capitalism: it maximizes profit while minimizing labor. It turns producers into artists and reintroduces finished commodities back into the cycle of production.”13

This distinction reveals something about the slipperiness of the poor sound: it is diasporic; it stems from longing and gravitates by love; it can be messy, unclear, collaborative, incoherent, inconsistent; it can assimilate with other tunes that undermine it. Sometimes, to find it, we have to listen hard. But once we do, it opens up to a common ground of non-narrated, non-instrumental possibilities. It can remain poor until it’s caught up by the machine.14

If digested by the machinery of mainstream media, its production values improve; it becomes crystal clear and, although it presents itself as inventive and pure, it is disseminated via an algorithm that is concerned with listener preferences — not their relation to the sound or its makers. It gravitates by interest in surplus accumulation through the monetization of information. It might just as easily contract, surround, diminish, kettle.

In March 2020, Steyerl added a paragraph to a conversation with Trevor Paglen that is reproduced in the catalogue. In it, she mentions that machine learning and surveillance technology might make positive contributions to “medical research” or create “stronger local networks,” but this optimism is tempered. “People like me used to say that about the internet too,” she says.