In an infamous scenario fit for a William Burroughs’ novel, the English mathematician and computer scientist Alan Turing (1912-1954) was forced by his government to take synthetic hormones to allegedly treat his homosexuality. This bizarre clinical experiment resulting in chemical castration happened in the years following the Second World War. Turing was his nation’s most brilliant cryptanalyst during the war. His accomplishments included a key victory in a battle for wartime secrecy, when Turing famously broke the Nazi naval fleet’s code known as Enigma to the astonishment of his peers and superiors.

Yet, despite his usefulness to society (or perhaps because of it) and though he made significant contributions as a computer science pioneer, the heart of the Turing story comes down to the fact that in the paranoid early years of the Cold War his sexual preference was considered a national security risk by the British intelligence community. Under intermittent government surveillance he died alone. Every era has its own brand of international hysteria, and there is something about the Turing story that makes it a stirring lesson no matter how many years pass. It is as though there was something uniquely tragic in his story that runs through all the many strange times that have come and gone since his death.

Yet, Henrik Olesen’s series “How Do I Make Myself a Body?” (2009) feels slightly different than other revivals. It relies heavily on Turing’s biography, but only in part because of the grizzly tale of clinical maltreatment and perverse medical cures. Olesen has more to tell us than the plain fact that routinely homophobia has been normalized and enacted as social control. Contrasting this ugly end to a meteoric career is a much more interesting subject: Alan Turing himself, separate from the story of entrapment. He is a subject who in Olesen’s work emerges as much more than a victim.

Social phobias that reinforce the pathologies of abnormality as related to sexual preference are here treated coolly in his art, as a sort of formula or algorithm. These visual equations are reformulated as narrative pieces running through the serial images Olesen makes of Englishman.

In The Future of the Image (2007) Jacques Rancière describes how modern art broke from the past by suspending everyday images between historical articulation and the ineffable experience of subjectivity. Something incommensurate betwen the experience of personhood and the experience of history describes a modern condition that also relates to Olesen’s Turing reprisal: “The image is no longer the codified expression of a thought or feeling. [Turing’s genius or victimhood could be an example.] Nor is it a double of a translation. It is a way in which things themselves speak and are silent. In a sense, it comes to lodge at the heart of things as their silent speech.” And this is a serene silence to the Olesen work on Turing. In part, Rancière refers to the shift away from universal religious and aesthetic codes to industrial types of encoding trapped within media’s mechanical competence. Similarly, Olesen’s images of Turing add the notion of silence and translation to the disquiet of prejudice or phobia that act en masse as automatic behaviors or affective expressions of automation that rule modern society.

Work dealing with affect by Olesen predate the Turing project. And example is the writing project Pre Post: Speaking Backwards (2006). Here we have a good example of how Olesen lifts source material in order to rearrange narratives inherited from the modern and pre-modern era. Each quotation he sources is arranged so as to be pushed beyond its contextual capacity to speak. Everything sounds like a secrete as they form what Rancière described above as the necessity of silence to create its own self-enclosed media language. To get to this precipice, Pre Post: Speaking Backwards collects writings related to performance art in the streets of New York (such as early Vito Acconci’s works), public forums for unsanctioned sexual activity (records of London’s public urinals), chance outings in an older, seedier New York (Marcel Duchamp and Charles Demuth) and regulations of private life (the infamous Buggery Act under which Turing was charged) to situate art history within an alternate chronology. The result is a kind of curated array in which we find archival sources and bits of information defy the expectations of their respective historical context.

Though this was a writing project, the outcome is consistent with the artist’s visual projects whereby the introduction of new images dislodges the research material from its source — and most crucially from the confines of straight history. (The straight has to been taken as either linear chronology or sexual identity). In Olesen’s words, his work uncovers a simple fact, “that even the most avant-garde, experimental (heterosexual) groups didn’t attract explicit visual homosexual cultural production or vice versa.” A recurrent premise found in his art, then, boils down to the idea that everything you know about modern art is wrong or fantastic, and that modern art cannot speak in fact, well, speak. At the very least we’ve been duped, and these heros turned into so many bits of information could have been stories retold in a different way.

This mode of inquisition and appropriation began Pre Post: Speaking Backwards (2007), but the general continuum works by finding solace in heterogeneous textual and visual fragments (not just one or the other). Once collected in a significant bulk these fragments are used to override the heterosexual and/or straight assumptions underlying the historical content the artist chooses to relay in his new artworks.

Surrealist artwork was one key source for Olesen as well. Starting in the 1920s, of course, the continental group made art that displaced 19th-century bourgeois values in various ways, literary and in visual art. Without disregarding this fact, Olesen’s Anthologie de l’amour sublime [Anthology of Sublime Love] (2003) remakes a Surrealist artist book to question what he considers the still lingering value systems of the 20th century — and suddenly the 20th century looks very Victorian. Similar to the works already discussed, the works asserts that homophobia constituted a blind spot even for the Surrealists. In this artist’s book based on an artist’s book, Olesen maintains the worlds-within-worlds atmosphere of Max Ernst’s original work, which he appropriates by adding to Ernst’s collages portraits of gay bondage and overtures of same-sex affection. Adding these fragments to the interiors of Ernst’s familiarly uncanny bedrooms creates renovated gay boudoirs where there was once Hansel and Gretel. The latter look more like the interwar avant-garde than ever before. But this détournement goes beyond what would be a pedestrian act of disturbing the original element of Surreal shock value in the pictures.

Rather, the Olesen work of Ernst’s book explores to what extent gay phobias linger in what is the very concept of the historical avant-garde. As was the case for the Surrealists, collage work amounted to an anatomical engagements with surfaces that visually reformulated and decontextualized out subconscious image of our psychic bodies. Additions to preexisting images magnify hidden psychological structures, in short. The new collages surrealize Surrealism, adding to it what Olesen clearly sees as more pleasurable, subconsciously omitted, gay content.

This said, Olesen is a gentle iconoclast. The additions have the air of homage, not rebuke. For there is a larger issue at stake, as he wrote in 2009: “Manipulation of Ernst’s collages in Anthologie de l’amour sublime was a direct examination of Surrealism and homophobia… I wanted to visualize the conflict — one that obviously goes much deeper than just Surrealism — inherent in looking at art history from the position of a non-heterosexual male.” Rewriting history as not merely straight goes beyond the privilege of bodily interventions. It is more than an encroachment on Ernst’s famous work. It refuses to take for granted any assumption that might shield the historical avant-garde from the very scrutiny it unleashed on art in the first half of the 20th century. To this end, it is very much in the vein of the source it affectionately co-opts.

If Anthologie de l’amour sublime acts as a kind of template for Olesen’s brand of revamped history, a basic — one could say democratic — sense of inclusion is usually an important element in the artist’s work. The work that concerns art history asks what kind of liberation, sexual or otherwise, the received mythos of that history chronicles as it pronounces, reiterates and repackages the canonical avant-garde, year in and year out. To his credit the artist gives open-ended responses that are free from simple oppositions of sexual preference or a dismissal of the straight sources he uses to drive his research, as the détournement of the Ernst book exemplifies.

Some Gay-Lesbian Artists and/or Artists Relevant to Homo-Social Culture Born Between c. 1300-1870 / Sex-Museum 2005-2007 (2007) is a set of series with slight alterations to the title. It relies not on the avant-garde but pre-modern art history to trace the emergence of homosexuality and the non-straight, while simultaneously paying homage to the eccentric scholarship of Aby Warburg.

As its title suggests, Warburg’s famous Mnemosyne Atlas (assembled between 1924 and 1929) was a map, one that charted the progression of European — especially Italian aesthetics. The Mnemosyne Atlas displayed reproductions of masterworks. A display of paintings and sculptures spread out in a grid across placards highlighted similarities across many centuries of art production. Warburg’s atlas isolates various grammatical orders in figurative art that lent the painted or drawn body a gestalt that connected it to an indelible social order in historical sequence.

What was in classical terms a means of representing a figure or subject as simultaneously symbolic, aesthetic and lifelike is placed in a matrix of social life by Olesen when he appropriates the Warburg trope for his contemporary art. Olesen collects some faggy gestures — Some Faggy Gestures is the title of a similar alternate series from 2010 — found in pre-modern artworks (c. 1300-1870). For Warburg, universal order was built into art—meaning that a collective social body could manifest itself in gestures at once artistic and affective, thus isolating the genus of genius, so to speak, and reveal a hidden overarching transhistorical order. Installation and juxtaposition was essential to this. Likewise, it is only via suggestion and juxtaposition of “faggy gestures” that a veiled and anti-classical narrative emerges in the selections offered up by the contemporary artist. In this sense it is an homage to Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas, which attempted to prove how ritualistic cultures were often already shared, even if subconsciously, and ready to converge if given the opportunity to be freed from their academic containers.

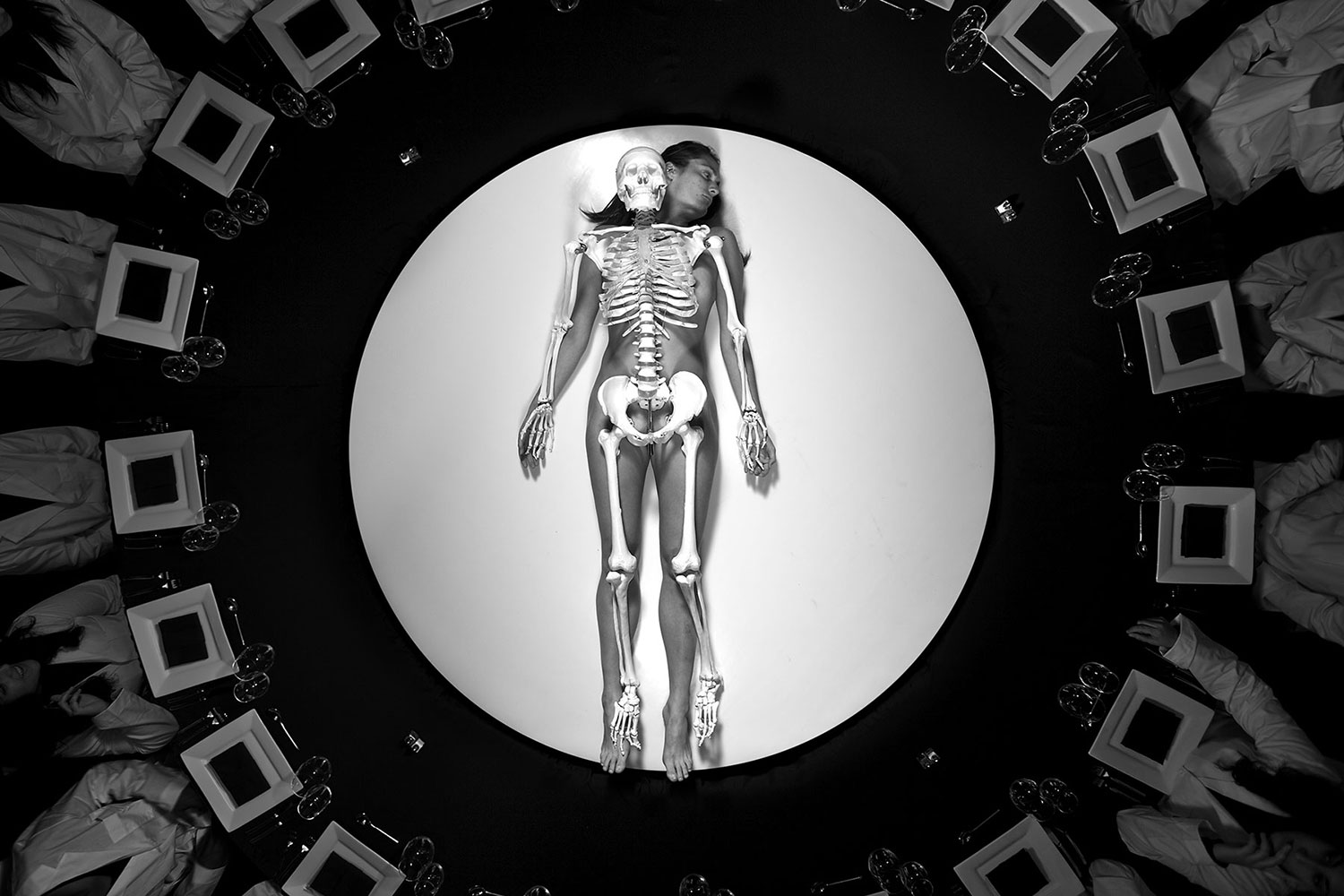

And in terms of subconscious content and returning to the Turing-themed installation How Do I Make Myself a Body? (2009), the images here consist of double-faced or obscured heads. These are suggestive of the hemispheres of conscious and unconscious mind. To my mind, some of Olesen’s reworked portraits of Turing recall the Janus faces found in the Surrealist works of Claude Cahun (1894-1954). Surely Cahun comes closer to the desired purview of open-ended inclusion that Olesen pursues. In the ’20s and ’s30s the French artist used the idea of the twin to assert sexual ambivalence and the power of endless transformation that can harness the past and the future in static pictorial space.Hers were staged portraits of a quasi-spiritual bent, more a self-religion harnessing life and death within highly own stylized pictures indistinguishable from her muted subjectivity.

The Alan Turing found in Olesen’s series also floats in an separate space that seems self-generated. Though not apparently like Cahun, the Olesen compositions are after-the-fact reflections of Turing’s cellular world that was created by his nonconformity and the social engineering project the government made of the incorrigible genius. Though he floats in the mystique of a mounting and unnecessary tragedy, in a space where we from the future know forces incapable of appreciation are destined to meet him, Olesen’s artwork seems to take in balance the fortunate consequences of Turing’s ordeal.

In Turing’s time, both his legacy and his arrest could have been framed as part of an advancement of social progress. At any rate, both his mistreatment and his genius point to the kind of bodily concessions available to the producing consumer today. “I see this series of collages as a menu,” Olesen writes, “where you can choose your own body.” If this sounds similar to the interfacing menus on a computer or an online storefront, it should. Olesen artistic gesture subtly points to the convergence of self-design and unrestricted control of the body from without. He neither endorses nor resists the role of “prosumer” (i.e. a productive consumer) that has become synonymous with technological advancements in Western individualism. The Turing work soberly looks at how patterns of consumption are deeply encrypted in the individual and how intimate control and industry is linked to the body.

Olesen has tied this idea to other works as well. “It flipped my mind to take my computer apart. […] It was like taking apart my own body,” Olesen said of I Do Not Go to Work Today. I Don’t Think I Go Tomorrow / Machine-Assemblage I-II (2010). Boris Groys writes that “the slogan of the previous age was ‘the private is political,’ whereas the true slogan of the Internet is ‘the political is private’.” To Groys, the digital sphere that makes everything an act of social networking and private consumption exposes personal taste. Henrik Olesen, too, has a knack for reversing these kinds of constructed relationships by starting with the imprint of the machine on the body.

The artwork of Olesen points to different registers of visual data that unravel like an unending Turing Machine tape. But, unlike a machine, the artist processes information in order to dissect social mores and behaviors that function like the binary code driving computing machines. Within this process of visual and historical dissection, heterosexual or straight history on its own constitutes but a fragment. It is zeros without ones — undifferentiated and therefore useless input values. Cutting into various meta-narratives is not new, but Olesen reveals how contemporary art remains an ever-shifting code that, once opened to history and allowed to wallow a bit in its native silence, gives way to researches more relevant for their pluralism. It is not just visual art. This push towards a separate binary or pluralism is as old as the avant-guard of course. Yet what is different is that today every alternative, every contrast contends with a startling computer-generated system of integration. Olesen seems to be wondering aloud if art will survive the networked monads of the computer age that are globalizing history as a creative endeavor, and doing so whether or not artists are there to intervene.