Maurizio Cattelan: I liked that blue woolen sweater you wore yesterday.

Helen Marten: Thanks. I borrowed it. It’s actually really huge when unfolded on the ground.

MC: Well then, so what about shopping and flatness?

HM: I love the violence of it, the brutality and coldness of objects frozen in display. But there’s a traction to it — the hilarious material pull entangled in the idea of frozen fashion; the idea that you might get your skin stuck, your lips caught. There is a stickiness despite the sanitization, the packaging. I walked into a beautiful tap shop recently and the reverence of it, the wealth, was practically ecclesiastical! But there was this amazing perversity in that all the taps worked and flowed into this giant urinal-like basin. You could use them all; it was so pornographic! And then all this latent eroticism is stripped back to flatness again when everything is graphicized back into consumption, into the catalogues — so delicious.

MC: So there’s a sickness parallel?

HM: Yes! I love that there’s this floppy malaise. And it’s contagious… a phlegmatic flood of wanting; the lungs are full of it! And all this dispersing (maybe you can’t use that word anymore), this generic ooze, is wonderfully viral.

MC: It’s connected to walking, right? To being a little bit naked…

HM: I love cities. So yes, the walking part is like unfolding a love letter; you’re stepping in and out of intimacies, the secret bits, the dirty parts. You can push the buttons you want to push, walk around with different lenses fitted — rinse your eyeballs or make them foggy! And doing it with someone else can be scarily lucid, erotic even. This nakedness — it’s how you fit your brain that day, whether you make a semi-conscious choice to see more, to connect at greater speed because there’s another set of intelligences there, another head to crack against, to rub up. So this nakedness is kind of juvenile, too, a quick-fire charge! It’s an immediate kind of wanting, a genuine haptic excitement.

MC: We will have to go for a walk!

HM: Sure. I often worry that artists can get into this hilarious kind of masturbatory practice… I mean, how it can be mean-spirited or self-congratulatory if all the hooks, all the one-liners, the loops, are a contented pat on the back: hermetic. Or the danger of rhythms of production that just become one type of ungenerous plodding. I like theft because it inherently bundles so many additional voices alongside this idea of a wicked gesture. There’s something of it in graffiti… rhizomatic chaos. But latently systematic, too.

MC: You mean like a kind of stunted smear campaign… But actually in the flurry there is method?

HM: Maybe. Yeah, I think so. I think there’s use-value in doing too many things at once; it means that you can accidentally fall over much closer to where you wanted to be, and without the route you initially planned…

MC: So you get lost a lot?

HM: Frequently. I can’t read clocks or maps. And I like the idea of touch colliding with real awfulness, a border perhaps, where trashy meets total formal seduction.

MC: Like makeup?

HM: Perfect. Tarting up art can go either way — like you’re either giving an acid peel, or really slapping on the foundation over a cracked or wobbly base! Material maneuvering could almost be like creating a pictogram… But in choosing the route you decide whether this silhouette is going to be quick or slow…

MC: How sharp the outlines will be…?

HM: Right. So in this idea of fuzziness and edges maybe we can make a wild leap to CGI.

MC: Common Gateway Interference? Like internet delegation?

HM: Ha! Perfect misunderstanding, right? No, I’m talking about computer graphics… Gorgeous 3-dimensionality in brain-twisting flatness: computer generated imagery…

MC: You’re talking a lot about things being flat, or flattened…

HM: Well, I want to know where all the information goes. How can you read the temperature of something that’s so instantly and seductively dishonest? I’m highly suspicious of compression. Although I’m totally not interested in this umbrella idea of “digital” things; there’s more flirtatious potential in the medieval… I’d rather get a semaphore than an email… Heraldry and hieroglyphs: the economy of it is wackily displaced…

MC: Unless you’re initiated…

HM: What is slippery is how the transferal functions, or how you can miraculously triple or half the content of a piece of information. And instantly, too, without the labor of finding the material to do it: the sweat and the dirt is eradicated, or at least momentarily obfuscated.

MC: This information shuffle is the same as all those taps flipping in and out real wetness to their starchy product pages.

HM: Just like that. But back to animation…

MC: …which is becoming a very hot method for making, no?

HM: I think it’s all to do with how miraculous it is as a “substance,” the infinity potential; there is a gorgeous fluid ease to the look of it, a blasé terror that is addictive. It’s weirdly ectoplasmic.

MC: But very difficult, of course — no? A very laborious process?

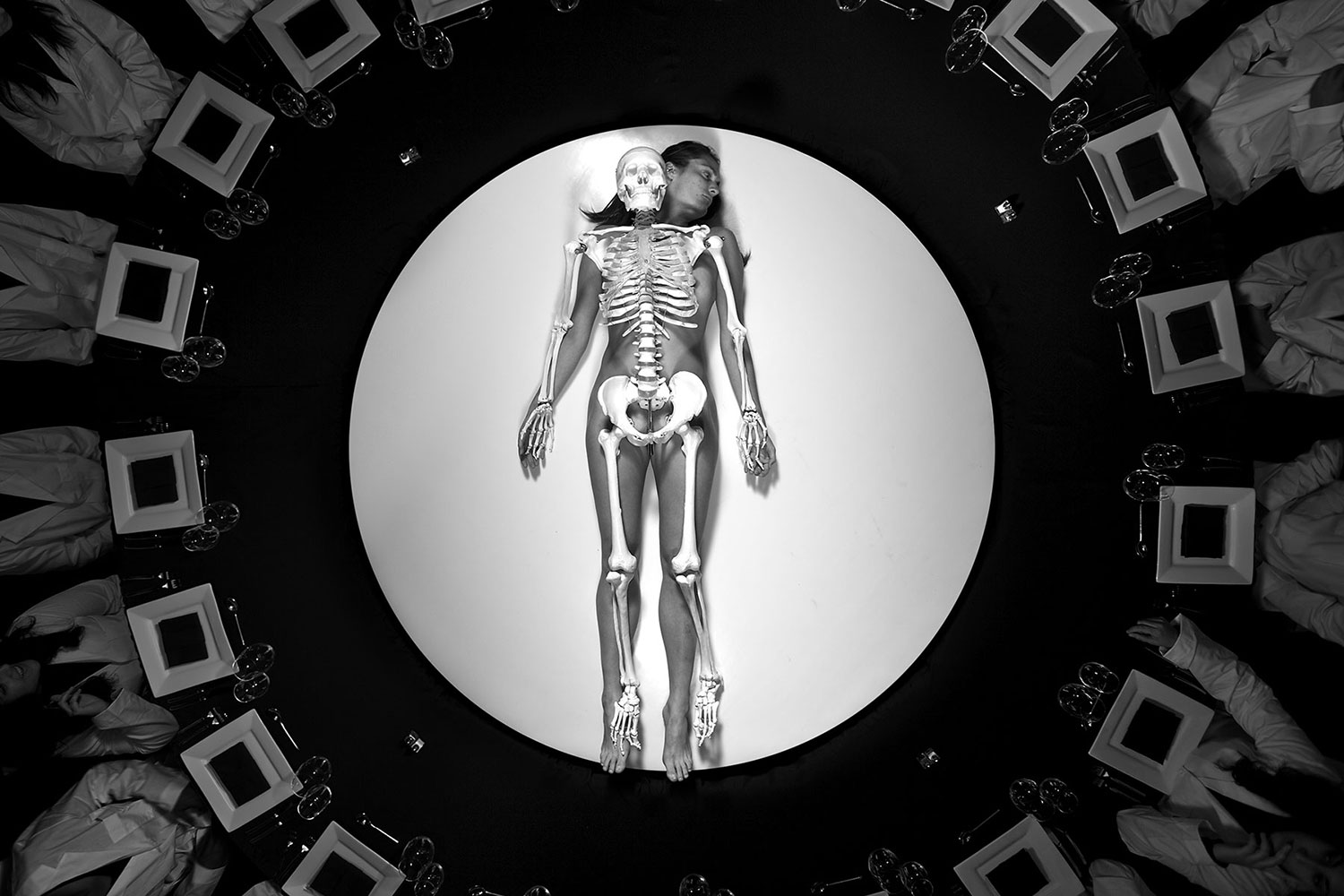

HM: Very. But there’s something too that’s linked to impatience — somehow a desire not to linger in the material world. But I find that idea very difficult, because I think that there is in some way a base philosophical crustiness to it all. Like in the process of rendering — in creating the final gloss of CGI, what you’re doing is layering skins and light in an algorithmic jumble that is actually incredibly fleshy. There’s rigging and calculation, so a very finger-tippy historical nod to puppet-making, a skeleton deftness of movement. And because there is often sound or audible text there’s a continual vice versa to it.

“No juice about it,” (2011). Courtesy Johann König, Berlin

MC: You have to listen as well as see…

HM: Except there is nothing to touch, no smell, just this weird rubbery shell that at that same time is both materially dead but data-osmotic! In some ways perhaps it is more code than text, and strangely weightless, genderless. So you’re tweaking different erogenous zones. And because the look is recognizable…

MC: Television, hoarding, billboards, traffic…

HM: Traffic, exactly, yes. So everything reflects back to total image, to shine and to package; take or leave what you need, when you need it. Spielberg’s Industrial Light and Magic idea is so alchemical. A universal elixir paradox!

MC: What kind of chemical high happens in the space of a blur?!

HM: Programmed hallucination!

MC: And this takes us to terror as well, right? To the usefulness of fear…

HM: Absolutely! Fear is like a jolting chemical flood that keeps the synapses in need of constant re-wiring — in a place where justifying is not just useful but essential to keep moving. There is a huge amount of comedy in fear: the ghoulishly cartoonish moment of hovering over the cliff chasm, but not being able to fall until you look down and the consciousness of the seeing triggers action.

MC: Comedy and violence have a pretty marauding history; cartoon punch-outs, stand-up — they’re so sadistic or masochistic.

HM: The brick on the head, the banana slip, the comic who forgets the lines — as images they’re really amazing graphic moments, such a tense tactile humor.

MC: You like the vaudevillian?!

HM: More the idea of dozens of errant banana skins that can read as bleaker metaphors when you realize that the alternate skid is into dog shit.

MC: So slapstick? But also somehow connecting lots of other dots?

HM: Kind of. The violence of the self-awareness in a stand up routine is terrifying, but jaw-droppingly brilliant. The poignancy and catharsis slippage is so knotty — how everything crumbles, only to be lightly built back up and then pitched further back into blackness. Comedy can be like a great emancipator or social condenser. The best is also so indecent, so taboo. The difficult mix of empathy, blatancy, language, repulsion, wrongness — it’s the same kind of tone I’m trying to find.

MC: Like sticking a Galliano shirt in a glass water bottle and persuading it to act like a Molotov cocktail? Such a poor one-liner!

HM: Ha! All thumbs! Sometimes it’s useful. The pathetic and the obvious can pretend be the opposite. This humanistic impulse to tidy away, to redirect the crumbs, is a funny one. I’m stealing directly from an SMS sent from a friend,* but extreme minimalism is just a fur coat turned inside out, a Benedictine attempt at denying our decorative nature…

MC: Sanitizing…

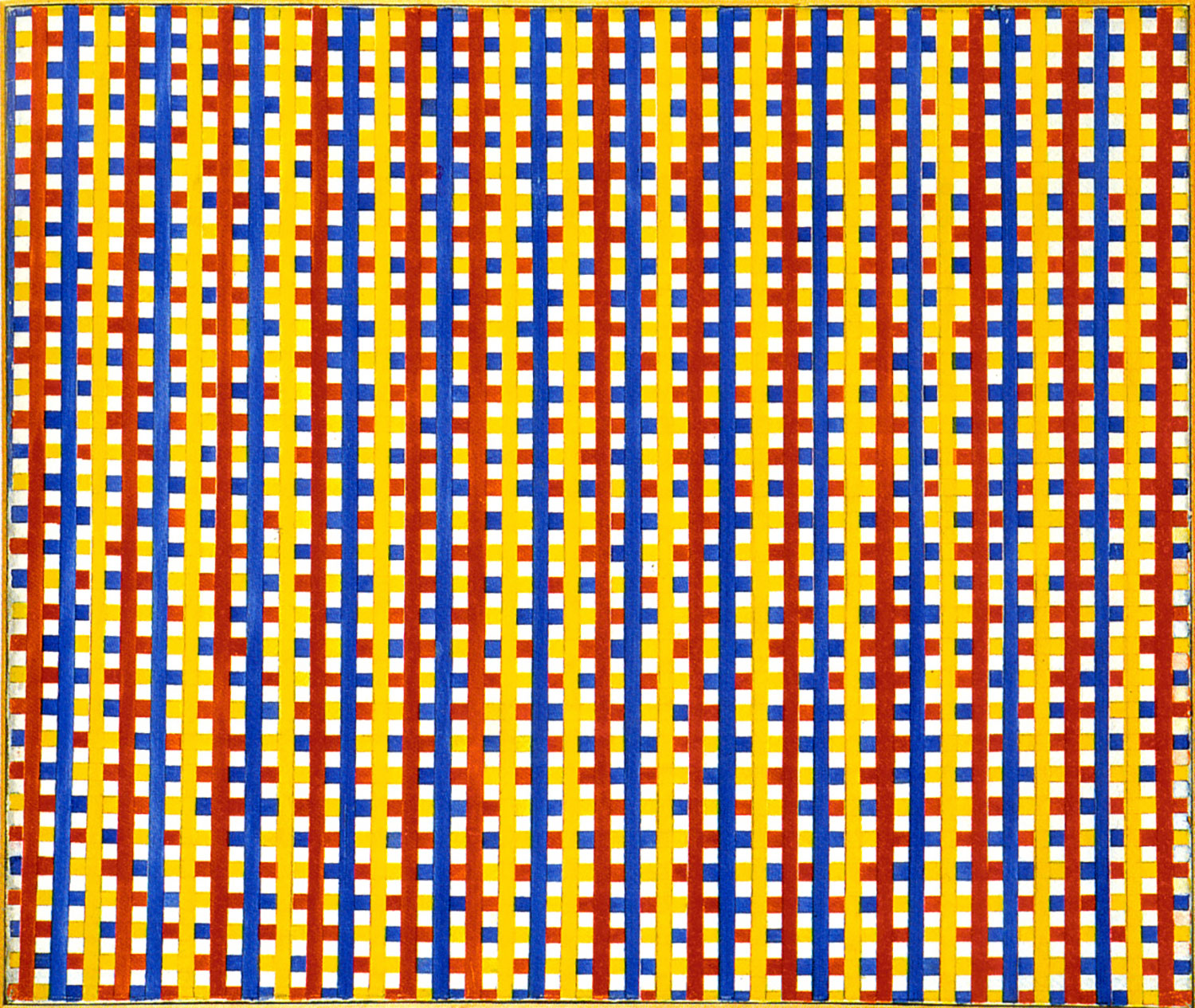

HM: When Hergé draws tartan or tweed patterns on his clothing, the lines stay in a grid, regardless of the volumes or twists that the fabric makes; the floppiness is treated with optical defiance. But the earnestness of the line is so believable: Egyptian in its retinal innocence, and such a great fiddle. So the cartoon men wear their own steel bars, and they’re political, but somehow detached so a child can read them. It’s a perfect piling up of absurdities, but stubbornly flat too. You get the same feeling with the porno Utamaro prints — how the stickiness of sex translates via the grating dryness of woodblock to a suggestive but ultimately condensed line.

MC: Can you namedrop somebody for me?

HM: Formica Benetton Andrex Crisco Festool Grape Nuts.

MC: Nuts!

HM: Of course. And everyone knows the name.

*Kit Grover, via Richard Wentworth, text message,

31 October 2011 8:30 pm.