The whole of my history in relation to computing really has had to do with a change from the notion of the computer as an imitation human being to the recognition of the computer as an independent entity that has its own capacities which are fundamentally different from the ones we have.

— Harold Cohen, 2011

Even before his first encounter with a computer at the ICA’s “Cybernetic Serendipity” exhibition in 1968, Harold Cohen’s (1928–2016) painting practice had already begun to resemble a formal codification, one played out during the mid-1960s in shows at the Whitechapel Gallery, Documenta 3 and the Venice Biennale. Works such as Before the Event (1963), in all their diagrammatic strangeness, effected a hinterland between representation and abstraction that begged the question that Cohen’s program AARON would later attempt to resolve: “What are the minimum conditions under which a set of marks functions as an image?”

With the Tate at one point exhibiting “Two Decorative Works by Henri Matisse and Harold Cohen,” the artist had reached an altitude at which he felt increasingly pressured to invent not only new paintings but also unceasingly new “worlds.” Cohen had always been committed to “the beholder’s share,” as Gombrich termed it, as well as what the artist referred to as “standing for-ness”: the way in which marks on a canvas evoke meanings personal to the viewer, and he firmly contested Clement Greenberg’s scientistic modernism both in person and in action. Yet for Cohen, who once described the computer as “a general-purpose symbol-manipulating machine,” the prospect of rerouting his experience into rules for a machine that made the art itself was a natural extension of his career’s conceptual arc, as well as a cure for creative exhaustion.

Over the next forty years, following his Wunderjahr of 1971, in the relative art wilderness of California, Cohen developed his second self, the program AARON, through a series of iterations written in the Lisp programming language learned during a stint as Guest Scholar at the AI Laboratory of Stanford University. As perhaps the oldest continuously developed program in the history of computing, AARON is uniquely capable of enlightening us as to the differences between human and machine learning. The stages of AARON’s development — from a drawing to a painting program to an online platform for mass printing — relied not only on the wholesale reexamination by Cohen of how he made artistic decisions but on his ability to compensate for one central problem: whereas humans’ cognitive systems develop by recourse to an external “real world,” an AI’s cognitive system has no external world to apply it to. AARON had to learn to see in the dark.

In seeking out the minimum conditions for which a set of marks functioned as an image –– and therefore the minimum requirements for AARON to exist as an artist –– Cohen sought out the “cognitive primitives” underlying visual perception. Over the course of the 1970s, AARON assumed within itself these universal skills: an ability to differentiate between figure and ground, between closed and open forms, as well as the capacity to develop a sketch based on what it had already drawn. This human approach to drawing in “feedback mode,” whereby individual lines and shapes are determined and measured in relation to an overall composition, was fundamental to Alberti’s Early Renaissance fixation on concinnitas. Yet in order for the program to attempt to replicate it, Cohen had to forbid AARON from drawing lines that overlapped other closed forms. Perspective would have to wait.

The murals produced for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1979 revealed AARON’s avoidance strategy in their chaotic balance of open and closed, bulbous and angular form, as well as cluttered and empty space. Rigged up to a mobile robot draftsman called the “Turtle,” visitors beheld the movements of AARON’s mind as it sketched out improvised compositions on the museum floor. At this point, Cohen was still hand-coloring his assistant’s drawings, but when the “Turtle” later evolved into a full-fledged painting robot, the artist observed the following:

To judge from the time people spent watching the machine painting, they evidently found it fascinating. But they went bananas when they saw it washing out its own cups, as if housework were the most engaging aspect of art.

For Cohen, art had become an epistemological problem more than an expressive, messy activity, and the robots ultimately proved a distraction.

Yet as the ’80s arrived, AARON was still groping in the dark. To make the leap from simple evocation to full representation, and from flatness to the illusion of three-dimensional space, Cohen drew on the analogy of a child’s early development. As recounted in Pamela McCorduck’s canonical work Aaron’s Code (1991), Cohen observed that the tendency of young children learning to draw by scribbling is invariably followed by the attempt to circumscribe that scribble, and so to embody something in their reality: “Mummy.” Inputting this “embodying procedure” into the program, coupled with the capacity to render overlapping forms, and therefore spatial relationships, AARON was able to produce works such as Adam and Eve (1986) that flirted heavily with figuration. Building on this development, Cohen suppressed the initial scribble so as to reveal external form without internal structure. Able to conceal some of what it had in mind, AARON was capable of constructing convincing and potentially infinite varieties of a small number of forms: rocks, plants, human figures and quadrupeds for which it had morphological schemata. In generating highly complex structures out of simple commands, Cohen achieved for the world of computing what was in fact Alan Turing’s single contribution to the field of biology, published in 1952 — his theory of morphogenesis, whereby identical cells are able to differentiate into organisms with arms, legs, a head, etc.

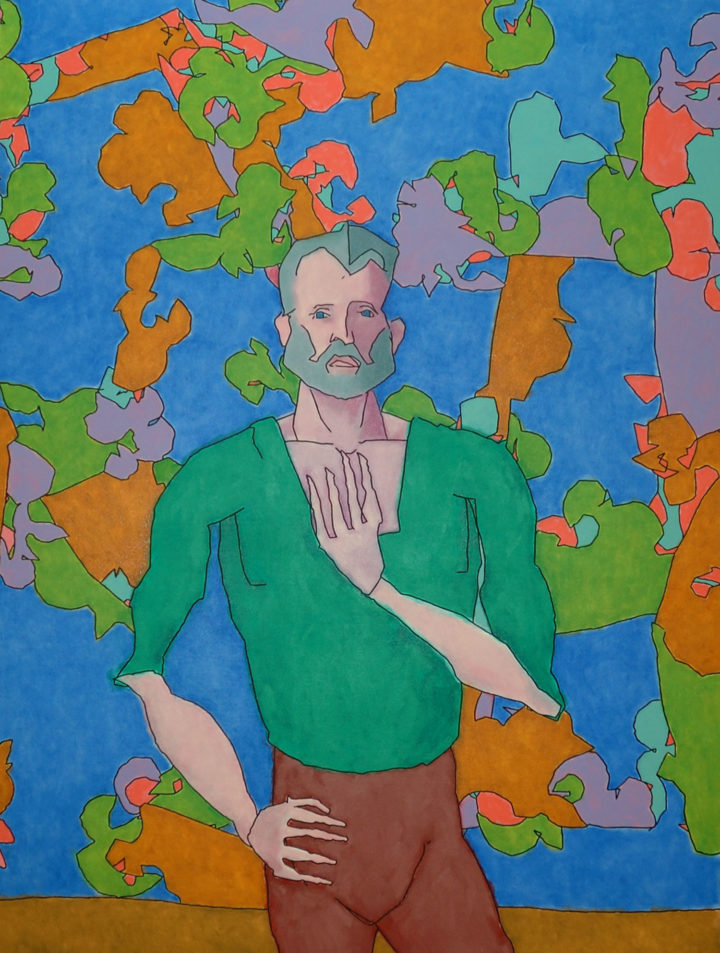

In AARON’s “portraits” of the early 1990s, a cast of almost-humans built entirely from scratch –– many of whom reminded Cohen of people he knew –– one witnesses the algorithm’s cognitive procedure in probably its clearest externalization. Works such as Two Friends with Potted Plant (1991) and Aaron, with Decorative Panel (1992) reveal, in their awkward foreshortenings and oddly distended anatomies, the problem of knowledge that is inherited but not empirically tested. Of course in their overt “two-and-a-half-dimensionality” they served as perfectly modern easel pictures, but the problems of representation seemed to determine AARON’s ultimate evolution into a colorist; Cohen certainly had no intention of producing yet another solids modeling program. Capable of “reasoning about color without seeing color,” AARON’s colorful imagination gave it an edge over its human collaborator, such that Cohen was never able to replicate the combination of values used to make AARON’s one and only “black painting.”

Toward the end of his life, Harold Cohen spoke of himself working “almost entirely in the program’s space.” Having constructed the equivalent of a musical score of infinite variations, AARON’s assistant had inverted the artist’s historical tendency toward self-mythification, as well as the requirement that art be expensive (Cohen often sold AARON’s drawings in the gallery at twenty-five dollars each, and in its web-based manifestation it became the first art-making program in history to provide original works of art on demand). AARON also consistently challenged the unwritten contract that dictated art show evidence of human intention, with Cohen gleaning from gallerygoers’ responses that it was enough for AARON to display “entitality” — that its works had a particular signature implying intention –– for it to exist as an artist in its own right. Should it have been subjected to the Turing test, under which machine intelligence is measured by its capacity for human communication, AARON’s art would be the work of a genius. The age of AI may augur a dystopian future, but AARON paints a picture of our second selves in color.