Spread across four floors and spanning six decades, Hans Haacke’s retrospective at the New Museum — his first museum show in the US in thirty years — engenders a lucid, matter-of-fact artistic exploration of income disparity, exploitation, institutional hypocrisy, and related issues. Haacke’s sculptures and installations are tied to specific historical contexts, but nonetheless continue to be socially and politically relevant to what’s happening inside and outside of art institutions.

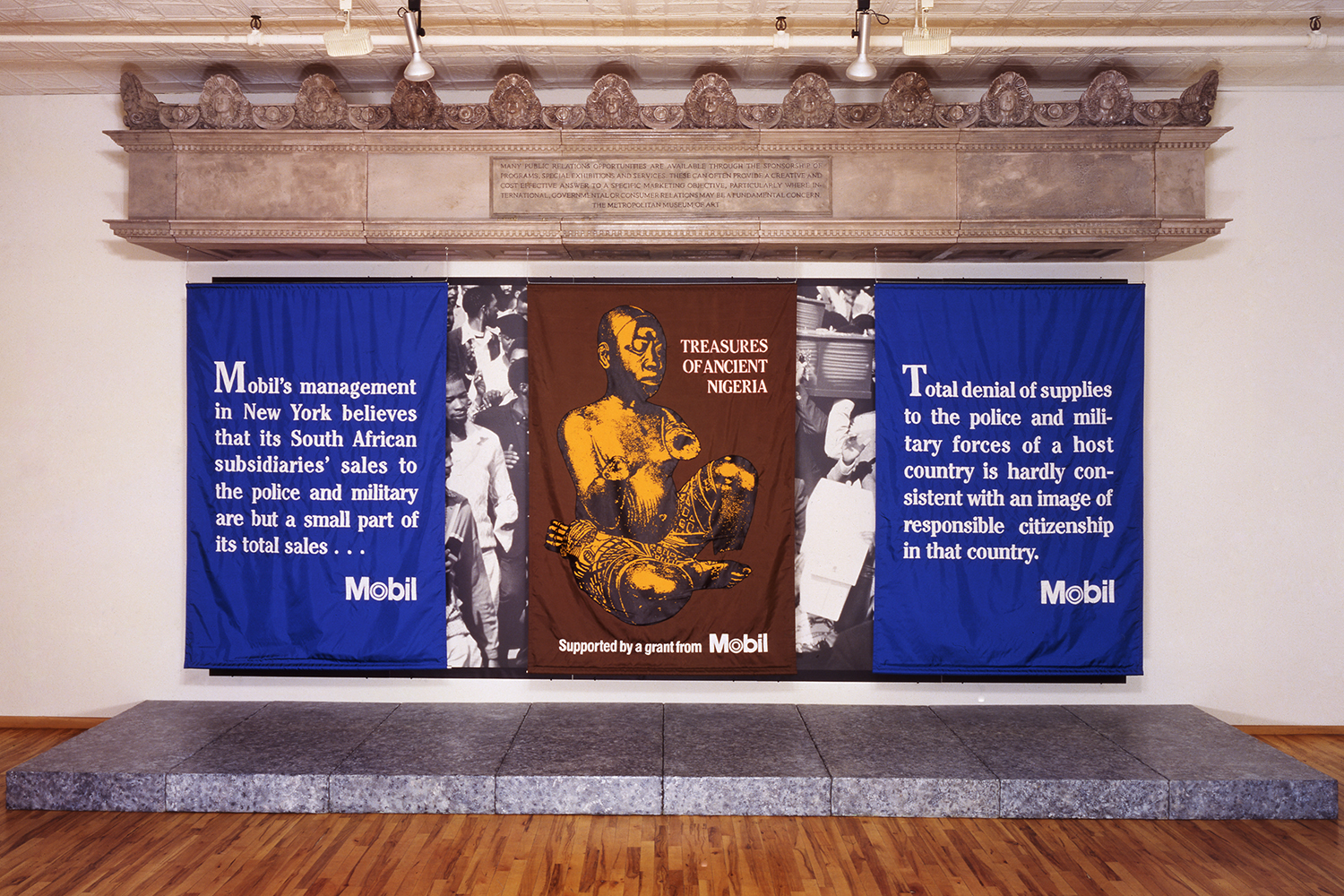

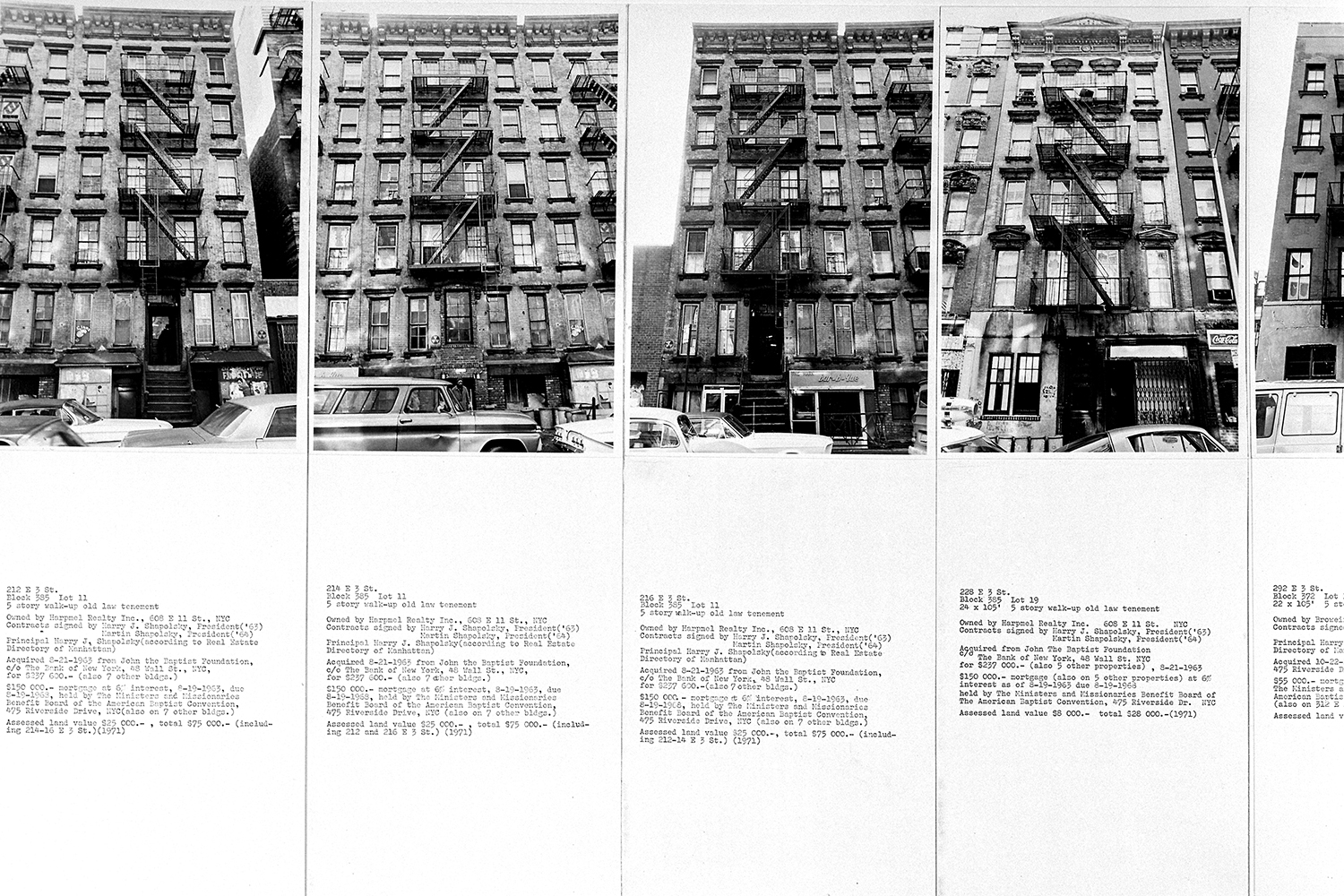

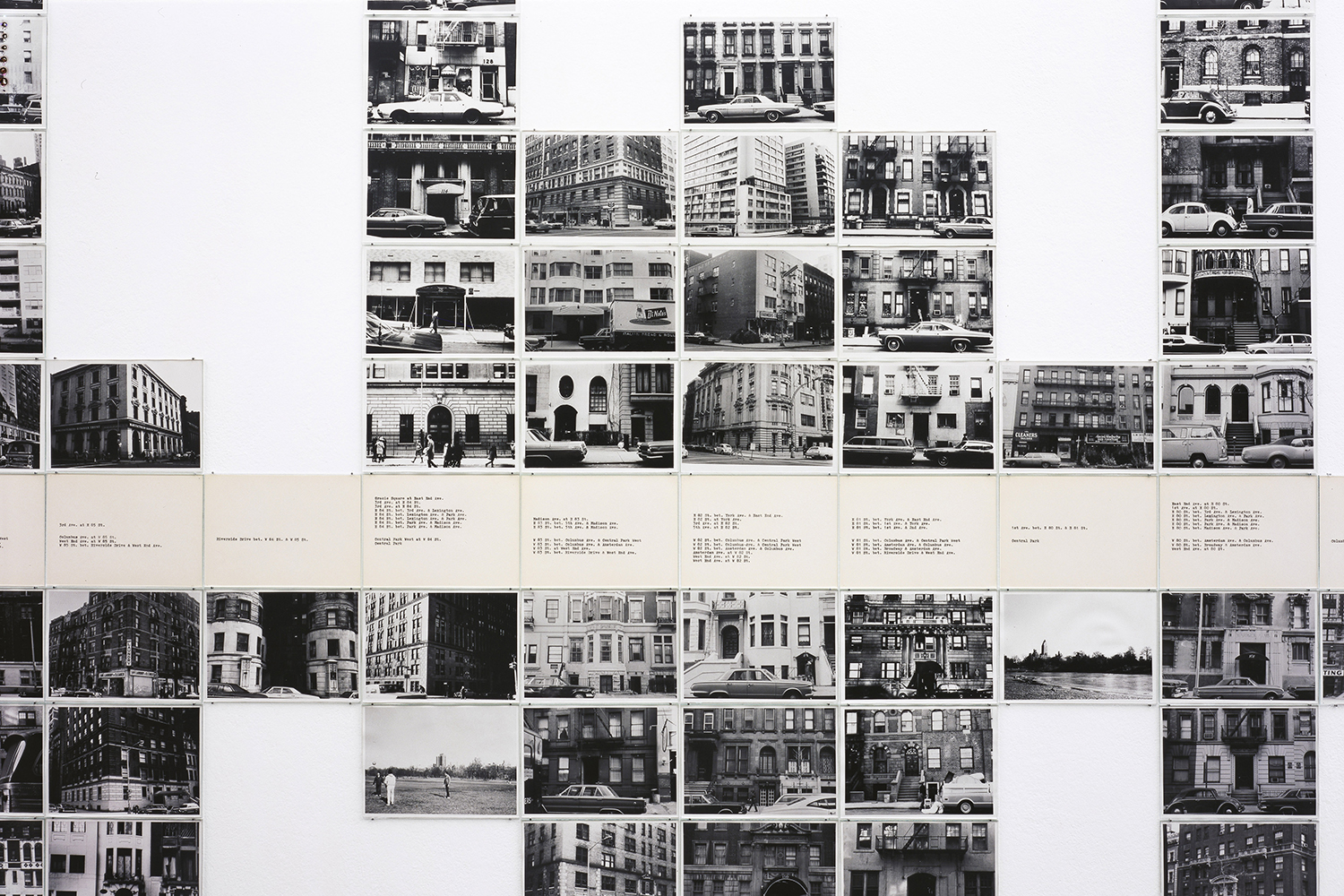

One of Haacke’s more recent and now iconic pieces, Gift Horse (2014), of a bronze horse skeleton, is prominently displayed on the fourth floor. The work was commissioned to sit atop the empty “fourth plinth” in London’s Trafalgar Square, which was originally “meant to carry an equestrian statue of William IV (1765–1837). [But] it is said that due to a lack of funds, he was never able to join his older brother, George IV (1762–1830), who is known for his ‘dissolute way of life’ and whose horseback effigy occupies the plinth on the northeast corner of the square” — so the wall label written by Haacke informs us. Aristocratic excess is hard for us to imagine today, but the bow-tied digital stock ticker attached to the horse’s leg reminds us that irresponsible financial behavior is still very much alive. Here, the work is surrounded by Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real-Estate Holdings, A Real Time Social System as of May 1, 1971 (1971), a work that was intended to be in the artist’s solo show at the Guggenheim Museum in 1971, but the exhibition was canceled. Through intricate diagrams and photos of properties found in public records, Haacke reveals the nefarious dealings of a “slumlord” real estate company. Though strictly speaking not a work of institutional critique, since none of the Guggenheim board were involved with the wrongs of the property company, the work clearly, if rather dryly, showed the interconnectedness of money, power, and exploitation — a calculus that Haacke has used numerous times since, and indeed has become the modus operandi of the institutional critique of museums.

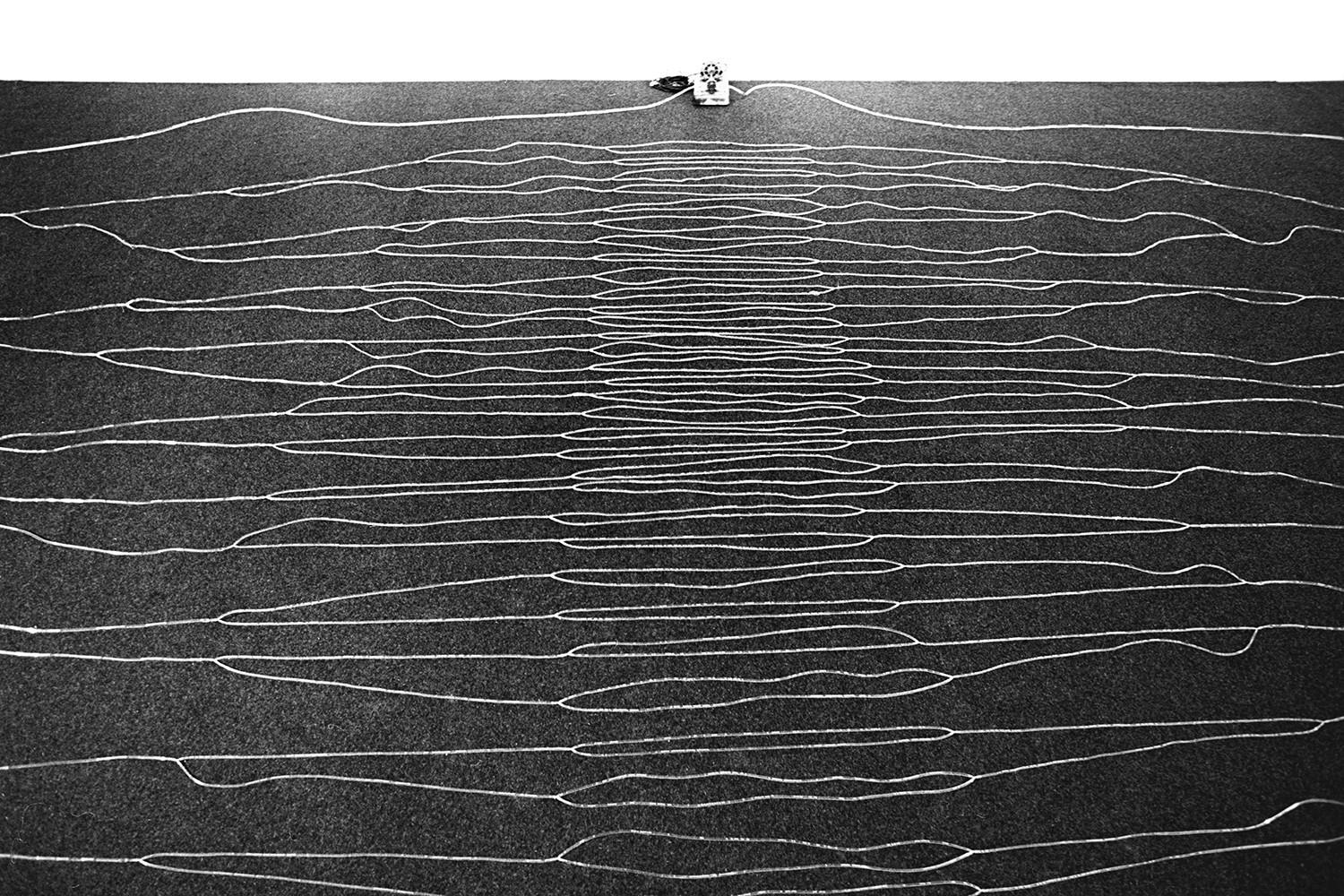

Moving away from Haacke’s politically charged art, one of the earliest pieces in the exhibition represents the German-born artist’s foray into conceptual art. Large Condensation Cube (1963–67) is a hermetically sealed Plexiglas cube that develops moisture on its interior based on the conditions of the room it is in. Haacke had excursions into many types of art, including environmental art, as in Grass Grows (1967–69), a heaped mound of earth with grass growing on it; and kinetic art, as in Blue Sail (1964–65), a square blue tarpaulin weighted in the corners and blown from below by a fan, creating floating, billowing blue ripples of fabric — one of the more fun works in the show. The uniting factor for Haacke’s works, however, is how all things — a tarp, the person watching it waft, the air in a museum, and the museum itself — are tied together through systems of connection: environmental, economic, and political. Younger artists have no doubt absorbed this lesson, but as Haacke’s poll works — such as MoMA Poll (1970) or his New Museum Visitors Poll(2019), which predictably confirms the left-leaning sensibilities of museumgoers — show us, the art world exists in a bubble, and one that needs to be popped sometimes.

Haacke has had a lasting impact on art as well as other artists. As Andrea Fraser notes in the exhibition catalogue, “Haacke may have been the first to understand and represent the full extent of the interplay between what is inside and outside the field of art” — something that “All Connected” does in spades.