The world contained in Graham Little’s drawings is one of effortless luxury and beauty, a women-only world where the main requirements are to look good and pose elegantly, maximizing the effects of the clothes worn and the hairstyles sported. The women here are strong, confident and powerful, and yet somehow without personality or opinion — one is easily interchangeable with the next, leaving only a memory of the stripes on a skirt or the tilt of a head. This is not to suggest that Little’s drawings are throwaway; in fact they are exquisite — honed and crafted over months to create an atmosphere more in keeping with a portrait by Gainsborough than with most contemporary artists, although comparisons with Elizabeth Peyton and John Currin are often made. Little’s sitters are not aristocracy or significant society figures though. They are models from glossy magazines, from old editions of Harpers & Queen as well as contemporary publications, and it is this contradiction, the intense study of something usually quickly flicked over, that makes his work so interesting.

The fascination of these women for Little has its roots in adolescence, in a sense of disappointment about being male and an over-awareness of the powerful ’80s image of the self-assured, emancipated female. “Being brought up in the ’70s I noticed that in advertising from the ’80s the man always came off looking stupid and the woman always looked super powerful,” he explains. “It’s easy to feel quite down being a man. That’s why I started making sculptures. I just loved women’s clothes and wanted to be part of that. I think it was that I didn’t like being a man.”

The intrigue was not a sexual one for Little, and his most recent series of drawings, shown earlier this year at Alison Jacques Gallery in London, is derived from fashion magazines from the same era, the pictures chosen specifically for their marked lack of sexual imagery in comparison to most fashion shoots today. “Pornography is so accepted in our culture now; in fact it’s odd when it’s not there,” says Little. “I guess that’s why the images of women I draw are so attractive — they seem softer, doing more gentle things. They’re incredibly exotic and beautiful, yet fairly non-sexual as well.”

With these new works, Little was also intrigued how the photographs from these top-quality ’80s magazines somehow did not match the fashion times they were in, containing none of the punk edginess that appeared in The Face or other prominent style magazines of the era. Instead the images have a gentleness to them that makes them appear slightly quaint and old-fashioned now, especially as punk has become the mainstream mode of expression in many forms of creativity. “They’re refreshing because the youth thing is everywhere now,” he says. “There are a few passports to success in contemporary art that I wanted to avoid — pornography, aggression or making work about the working classes. These seem to be used a lot and I find it can lack honesty.” Little’s drawings deliberately avoid the easy acceptability of popular culture, choosing instead to use a more traditional style — ironically a rather dangerous route to take now in the contemporary art world. “I think the punk ethic has come back and now people are perhaps more scared to make gentle, immaculate work,” he says. “People are still really cautious of being seen as Sunday painters or verging on that.”

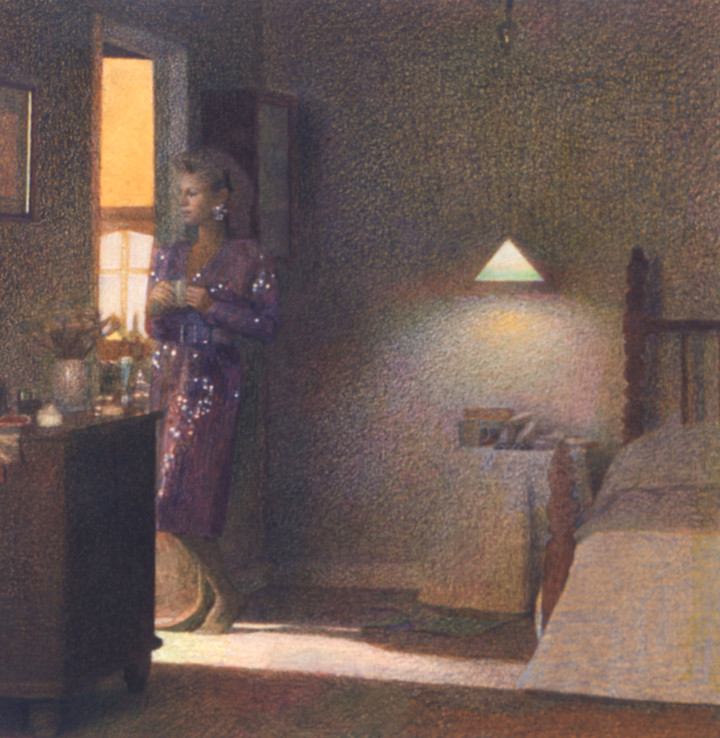

His latest drawings also contain a sense of narrative that is absent from his earlier works, which focused solely on the models, placing them against a sketchy or undefined background. There is almost a cinematic quality here with one woman portrayed gazing wistfully out of a bedroom window, while another is interrupted by a phone call while typing. For Little, these works are more emotional than his previous drawings, and he’s keen to explore his subjects’ moods and attempt to understand what they are feeling. Regardless of this, there’s still a marked lack of reality, through both the exaggerated posing and the absence of expression. This lack of individuality continues in his naming of the works, which all remain untitled, though Little disputes that his drawings are portraying idealized versions of women, arguing instead that “maybe they are a generalization. It helps me to deal with the fact that I’m a man — for a while I can be the woman in that world. The works come instinctively but this is my guess about my motives. I think that’s why they’re all so well honed; I completely immerse myself in that dream.”

In contrast to the restraint of his drawings, Little’s sculptures seem to be buzzing with words. Awkwardly shaped and erupting in every direction, these works could easily be quirky design artifacts instead of art. Yet they evolved directly from painting when, as Little puts it, “things got so huge, they had to be on the floor.” The artist continues to relate to the works as paintings, no matter how different the effect on the viewer is. In the work A huge mass of luminous gas erupted from Mars and sped towards Earth (2003) it’s virtually impossible to view the piece in its entirety from any one angle, and its many sides exhibit patterns ranging from the stripes and geometric shapes of fashion design to circles, triangles and bubbles. The titles of the sculptures alone, most of a similar length and style, emphasize how different the sculptures are from the drawings, and while for Little the titles exist simply to guide the viewer with these more abstract works, they are also fitting for the hectic quality the sculptures evoke. The names of the pieces also make direct reference to popular culture, with A Huge Mass… taking its name from Jeff Wayne’s concept album The War of the Worlds, while other works have name-checked ’80s UK television series Howard’s Way and Jean Michel Jarre, as well as various fashion designers.

The sense of speed in the sculptural works is intentional, and while the drawings aim for an intense stillness, even isolation, the sculptures are instead trying to capture an excited impression of the world flitting by. A Huge Mass… was in fact inspired by Little’s experience of roller-skating around London, and tries to depict all the textures and colors he glimpsed as he glided around. Like the drawings, these works are absorbed in the surface beauty of life, in portraying the intense pleasure in what is seen every day and usually taken for granted, or at least rarely scrutinized. The importance of surface becomes even more apparent on discovering that Little’s sculptures are constructed using MDF, a material known for its cheapness and easy availability, which seems to belie the immaculate objects it becomes. The sculptures also serve as gentle mockery of our minimal furniture preferences and the dominance of Habitat and IKEA in our design of the home. “They’re vandalizing the IKEA furniture habit that’s taken over from anything old-fashioned,” explains Little. “I wanted to make my own version of something that was visually rich, but I had to do my 21st-century version, which of course also relates to IKEA, you can’t get away from that.”

Little’s art holds an interesting place in the perennial and somewhat tedious debate over the relevance of painting in 21st-century art. While sighing somewhat when the subject is raised, he acknowledges why the discussion won’t seem to go away, no matter how much important and relevant painting is produced in contemporary art. “In every decade there have always been exciting painters, but in some ways I understand the criticism of painting in terms of the work I do,” he comments. “In Gainsborough’s time, painting held everything — there was no TV, no posters or magazines. They had to show all the fashions of the time and be the storytellers in the way that TV is now. Now painting’s had that all taken away. In that sense it’s hard, but like everything else this gives it room to change.”

Little’s drawings and sculptures are firmly contemporary in their subject matter, commenting on our beauty-obsessed society and on our increasingly sophisticated ability to dissect and absorb the imagery that constantly bombards us. Yet his work is equally instilled with a sense of nostalgia for a time when things were slower and less aggressive, and this is expressed in the earnest, methodical way his works are made and presented. It is perhaps here that Little’s art is at its most honest, openly admitting all its influences, yet consistently adapting them into something modern. “I think art always is nostalgic,” he acknowledges. “Either for something that doesn’t exist that you wish did or for something that once existed and now doesn’t. Or maybe never did.”