A conversation

Adam Pendleton: What are you reading these days Glenn?

Glenn Ligon: I started reading fiction again after a long break. I’m reading The World As I Found It (1987) by Bruce Duffy. It’s a novel that imagines the relationship between Wittgenstein, Bertrand Russell and G.E. Moore. It’s a very vivid work of fiction about Wittgenstein and his circle, but what’s also interesting is it dives into the philosophical material that they’re working on within the time period the novel was set. I think it’s pretty rare that a novel makes complex philosophical enquires intelligible, and in a style that is incredibly page-turny. What are you reading Adam? Do you always read for work?

AP: That’s a good question. It’s hard to do both — read for work and read not for work. There’s often not enough time. There are always stacks of books in the house. Downstairs are stacks that are typically specifically related to work. Upstairs, next to the bed, is a stack that’s supposedly not related to work, but these divisions are superfluous in the end.

GL: Does the upstairs stack contain poetry books or plays?

AP: I actually don’t read that much poetry. I tend to read the critical writing of poets more than their poetry. Downstairs is a book like Novas, the selected writings of the Brazilian concrete poet Haroldo de Campos, which includes his critical writings, and upstairs is a book like Remainder (2005) by the British novelist and conceptual artist Tom McCarthy.

GL: I always find that I don’t know how to read poetry. No mode of reading seems satisfactory to me. Maybe the space that is required to read poetry I can’t make for myself very often. I find myself skimming. You can’t really skim poetry…

AP: That’s funny because I often do skim poetry. I look at it as material for fragments. I’m OK with moving in and out of the space in that way.

GL: I think we’re in a moment that privileges fragments because of the speed at which information is available to us. Either I’m skimming a text or I’m reading it incredibly slowly.

AP: Maybe it’s a contradiction to say “fragment” and then also that I read to remember. I consider all of the decisions that have been made, what’s been included, what hasn’t, how it has been framed. Is that a part of why you read slowly?

GL: Partially. When I was in college I’d read books to figure out how to be. I was very curious about how people lived in the world, and so I’d read a lot of biographies, just to see how do you do this thing called life. I realized that while you’ve always approached books as material to take fragments from, allowing the viewer to reform and make meaning from those fragments, I tend to feel much more bound by the author’s sense of what that text means: that’s the starting point. And then making the objects is a little bit of a fight against that authorial point of view.

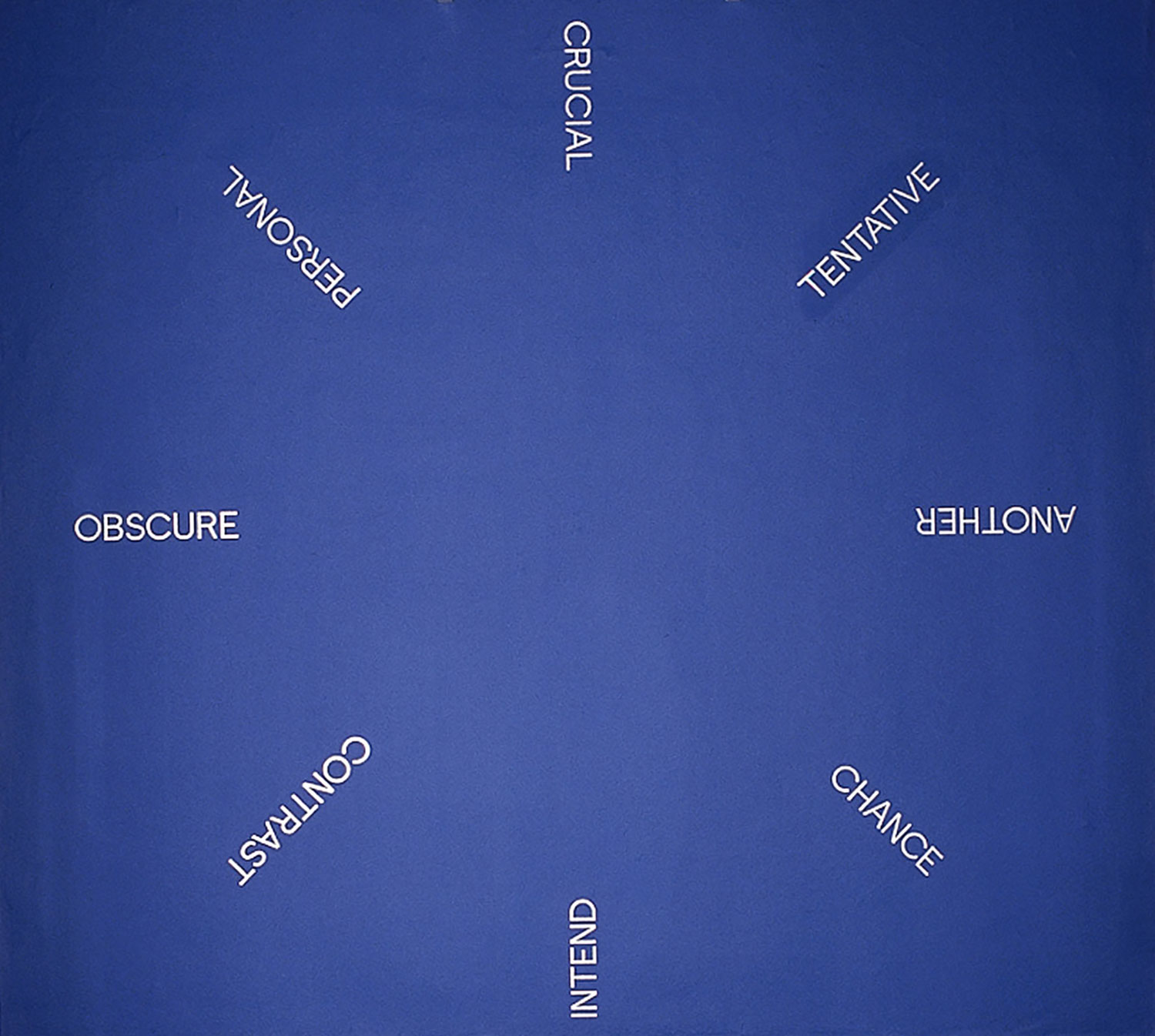

AP: To put it plainly, the use of language in your work serves to move away from what you’ve interpreted as a fixed meaning of a particular text.

GL: The transformation of a sentence or a text, the way it’s placed on a canvas, the way the text breaks down, is a strategy to move myself away from the specific meanings that I’ve given to the text. But also, in some way, to move the reader from some very easy formulation. The meaning of the words changes as I’m making the work. So the meaning of a text that I was initially attracted to changes through the operation of making a painting or a neon.

AP: So do you consider these texts to become yours?

GL: I don’t know. I don’t think they become mine. I described them other times like doing a film adaptation of a novel. The medium you’re working in has its own logic and rules, and you have to make choices that are not the same choices you would make in the original medium.

AP: But it’s certainly about contributing.

GL: Right, it’s an interface between you and the text. I think of the possibility, in your work, of the interface between the viewer and these text fragments particularly in relation to the body of work, “System of Display,” that has mirrors in it.

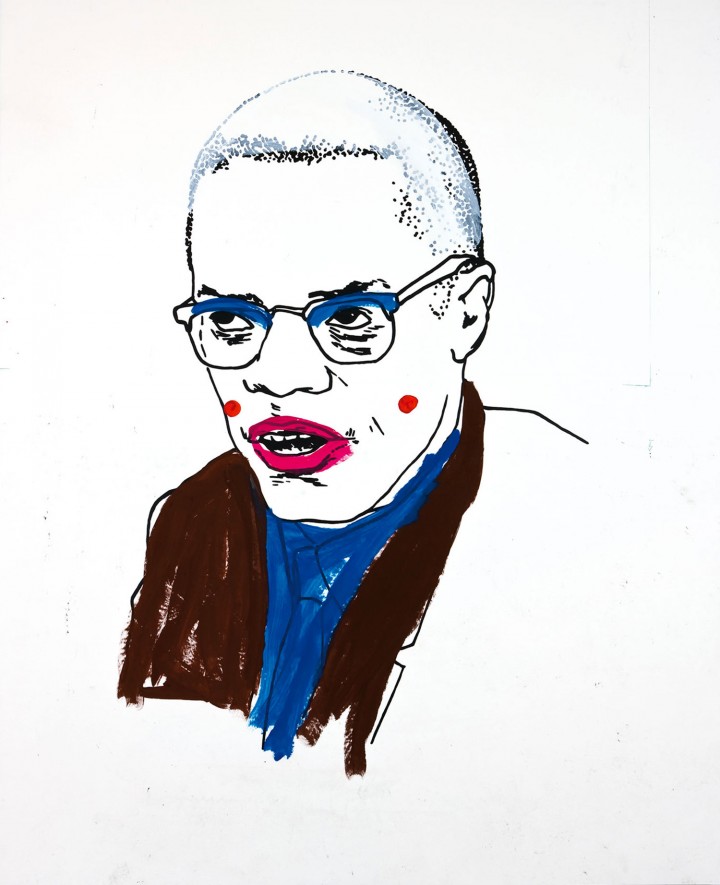

AP: Yes, the “System of Display.” I also think of the “Black Dada” paintings in this way. These works ask the viewer to establish new relationships to both language and image. I like the fact that people don’t know how to “read” the language in these works, even though the titles, from a practical standpoint, give you everything you need to know. It’s interesting how a concretion of language, for many, explicitly moves away from a factual position towards a purely experiential one, but I would argue that they are one in the same.

GL: Viewers sometimes don’t recognize they have skills; most images we see come from the television or movies or magazines, and are meant to be digested in a certain way. To provide a space for the viewer to exercise this kind of underutilized sophistication about reading images is an interesting project. Also, technology has broadened the idea of context. Any text that you use operates in its original context and operates in radically new ways.

AP: Meaning is always present. But the question I ask myself is when does meaning return to the body as a site of engagement? That is why I return to the idea of the body as both a physical and intellectual site. Now, in 30 seconds, you can construct a body of knowledge around something. But isn’t that kind of knowledge about forgetting or forgetfulness? People forget the information they glean from web searches in a couple of hours or minutes even. How do we get people to engage with these “meanings” from a physical space?

GL: Do you think certain forms of your practice do that more succinctly than others?

AP: I think I address that notion in many different ways. My publishing projects, the “Black Dada” paintings, and BAND (2010) do it in different ways. One is not more successful than the other. These things in relation to each other create a site where we move beyond just registering information.

GL: I am curious about the different strategies that are employed in different works to make the body as a site of engagement happen. Obviously in “System of Display” it’s about the putting together of images, and allowing the viewers see themselves during this operation.

For example, in BAND, because of the multi-screen format, your attention has to shift because you are watching three screens and multiple viewpoints on the same action.

AP: I’ve always wanted to ask you how you feel about the conversations that you have about your work and the language that is attached to the work. Are they as you want them to be?

GL: Often not. I think one has to be quite vigilant about what one says because those things follow you forever. It was instructive when working on my retrospective at the Whitney Museum to go and look at all the things that have been written. I could see the beginnings of a certain kind of trajectory in the critical writing around the work. To change that direction is very difficult.

AP: It is. It becomes rather pervasive and powerful. I do think certain strategies can be used to move the conversation along. That’s one of the reasons I’ve started to compose books that collect texts and images related to the work. The designers I collaborate with say I am building my own library. I like this idea.

You could almost say there have been three bodies of knowledge around your work historically. You could say more, but I’m thinking about it in terms of the publications Unbecoming (1998), Some Changes (2005) and now America (2011). For each of these, one would assume, you were a part of the process of “What do we want to talk about and why?” This week I re-read the Unbecoming catalogue: that could not be a catalogue for today.

[both laugh]

GL: We have to make our own books. In the Some Changes catalogue I was pretty deliberate about the fact that the voices that I wanted in the book were divergent, and so there are essays that took very different approaches. Some were much more about source material and engagement with history. And I felt both of those approaches were valid, but now I’m more interested in a text that can do both at the same time. So, yes, one has to be vigilant about how rigorously people approach one’s work. But I find it a burden.

AP: I think I found it a burden at one point. I think the first works that were shown publicly raised a lot of questions. But the conversation that was beginning was not one I could have publicly.

GL: I think that artists have to be engaged into the discourse around their work. Now it is more urgent. Take the things I’ve written for art magazines: often I’m frustrated about the fact that one has to start from very basic conversations.

AP: Silence can be useful as well. One of my ongoing projects (and this goes back to your question “Do you only read for work?”) is not only creating language for the work, but a vocabulary in general. Creating new vocabularies for how we look at, approach and address material is one of the only ways to make information truly register with and for people. That’s why I’m always looking at a variety of linguistic and visual representations. Darby English once wrote that your work exhibits a “commitment to the difficult.” It’s a useful commitment, which is why it’s so important to make a decision about narrative, because narrative is usually about creating a foundation for people to understand things. I wonder how you would see yourself moving forward in that way. Do you feel as though you’ve created narratives that you can move forward with, or are you mostly interested in new ones?

GL: I’m more interested in working in mediums I haven’t explored very well, like video. I am also interested in the artists I was interested in when I started making work, like Cy Twombly, Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning, and I often ask myself: “What does it mean to go back to the abstraction I was in love with when I was in college?” You know, it’s not 1955. How do you bring that practice into the present? That’s what I’m excited about.

AP: You say your interest is moving towards video. I think paintings are cinematic for sure.

GL: Painting has become cinematic. Even when it’s abstract, a painting is very engaged with the cinematic, with the images. I am interested in painting that attempts to be other things.

AP: I saw the Baldessari retrospective at the Met. It was surprisingly refreshing to see. Something he said, that I often say to myself, is that “we walk around with movies in our heads.” It sounds like you are thinking about film through the discourse of Abstract Expressionism.

GL: A film project I did called The Death of Tom (2008) started out as a narrative film but turned into abstraction; but curiously enough it turned back into a narrative film with the addition of a score by the pianist Jason Moran. I’m curious about what a painter (as I still call myself) can bring to those cinematic spaces. The Baldessari quote is very relevant in the aftermath of 9/11: people often say, “It’s just like a movie!” It’s almost as if the real is the movie, as the only way we can organize our thoughts is through the cinematic.

AP: Particularly with projects like “System of Display” and “Black Dada” I attempt to empty my mind of these images. It’s also something I feel you do in your work. Feeling that you have nothing left is actually very encouraging; it’s a good place to be. I wrote this down: “…pleasure is possible even in a situation of unrelieved frustration.” It’s a Jacqueline Rose quote in regards to your work.

GL: There are things that I know how to do. I know how to make a painting that looks good; it’s easy, and to work against that facility is always interesting to me.

AP: It’s funny because that is something that people have just started to think about in regards to your work. Would you agree with that?

GL: A lot of the discourse overly focused on social aspects and political engagements, and not enough on formal qualities. In some ways I am a very old-fashion painter. Beauty matters to me; that’s where the work starts. The things I said about the struggle to create meaning and the legibility issues are all there, but there are formal issues that I’m engaged with that haven’t gotten quite enough play. As you said, people are just starting to look at the paintings now.

AP: For me this brings back that notion of emptying out a space. Now people are able to step into the space you’ve created. A lot of the work that I am interested in has some relationship to or is an investigation of the documentary. I’ve always thought of my works as “documents” of image, of language, and I’ve often thought of your work in the same way, specifically projects like A Feast of Scraps (1994-98), even Day of Absence (1996) or The Orange and Blue Feelings (2003).

GL: I think there’s some bodies of work that try to work against what documentary film might be. The Orange and Blue Feelings was based on a discussion with a therapist. I thought it would be interesting to make a video that promises the inside view of a relationship between a therapist and their client. But you never quite grasp it because you’re thrown in the middle of the therapeutic discussion and there’s a lot of material that the viewer doesn’t have access to. Also you don’t have access to me in other ways, and you only hear my voice and I don’t appear on screen. So it only promises the authenticity of the therapy session… But you’re talking, I guess, more conceptually about documents. One of the things that was interesting to me in Day of Absence was the use of newspaper photographs of an event, the Million Man March. I was curious about what happens when images you use are loosened from framing devices, like captions, that make those images intelligible. One of the things I was fascinated by was how people become visible and invisible. The Million Man March was a rallying of black masculinity on the mall of Washington DC, a rally organized around the absence of women. The absence that structured the march was what I was trying to bring out in my use of the photographs, and the way I did that was a similar process to what you do when you use photographs: I Xeroxed them, enlarged them, and in that process they became indistinct. The images fill in, information drops out, and so these absences and voids get teased out of the image.

AP: I had no idea you Xeroxed those. I Xerox every image I use. The copy machine is the queen of the studio! It renders a certain level of anonymity but in a certain way also contributes very specific formal qualities that I am interested in.

GL: Specific in the sense that your intervention becomes much more apparent? If you flatten that image out, the source material becomes less apparent and that allows the image to float freer.

AP: Which is why I Xerox. The Million Man March works also have a painterly quality.

GL: It is because they’re silk-screened one, two or three times, and silk screen can be an imprecise form. The moment when a silk screener presses too hard or too lightly or mis-registers the image is the moment when I’m happiest, when those things are not controllable. What are you working on these days?

AP: I’m working on a new group of “Black Dada” paintings. The idea of “Black Dada” has changed in so many ways. I’ve been thinking a lot about the work of Ellsworth Kelly with this new group. At times I’m only aware of the phrase as a “B” or a “K.” I’m also interested in the work of the writer Joan Retallack, hopefully for a film project. Joan has done a lot of scholarship on the work of Gertrude Stein and John Cage. I’d like to use some of the ideas that their work raises to look at Joan’s own work. It’s tentatively called A Portrait, and I hope in some ways it will be like a Gertrude Stein textual portrait.

GL: Do you anchor projects in a text usually? Be that a movie or a novel?

AP: I always have to begin with something. It’s a lot of research, shifting through materials. I’ll write a text to move ideas along. I need to be deeply curious, in trouble, on edge even. What about you Glenn?

GL: Everything is now kind of potential. I’m very interested in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1951). At this point it’s a classic, it’s an over-determined text. But what I’m really interested in is Ellison as a figure writing a novel. Reading his biography I was struck by the notion of him sitting at his desk with Fanny, his wife, in the other room typing up his manuscripts for him, and I am using that as a structure to organize a film project around the artist sitting, working on something, daydreaming essentially. Again, I don’t know where this project will go. I have to do way more research. I’m also interested in abstraction. I want to figure out what that might mean, how it’d work for me. I’ve been very interested in looking at people like Twombly again, because so much of my work has been text based, and so much of his work has been about the things that come before text: the scribble, the scrawl, the random mark, the mark that approaches writing but doesn’t quite get there, but still conveys some kind of meaning and legibility.