Statements about Germano Celant’s contribution to conceptual art usually limit themselves to invoking his invention of the notion of arte povera and mentioning the exhibitions he curated. But meticulous analysis of the genesis of post-minimalist conceptual art and its dissemination1 shows that his first exhibitions and critical texts constitute its first iterations. From a chronological, artistic, and theoretical point of view, “Arte Povera-Im Spazio” (Galleria La Bertesca, Genoa, September 27 – October 20, 1967), “Arte Povera” (Galleria de’ Foscherari, Bologna, February 24 – March 15, 1968), and “Arte Povera più Azioni Povere” (Antichi Arsenali di Amalfi, October 4 – 6, 1968) form the prolegomena to the major post-minimalist conceptual art exhibitions.2

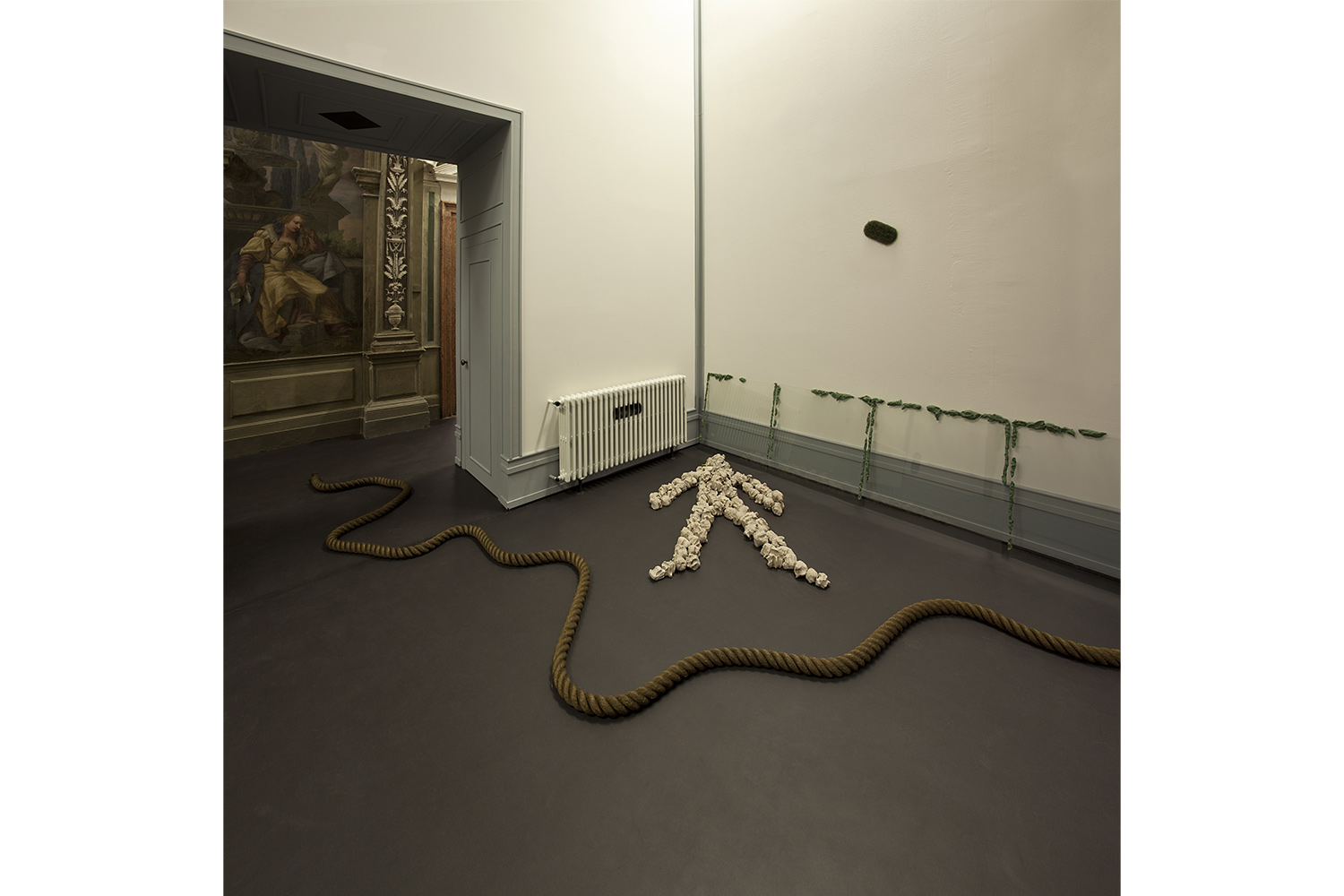

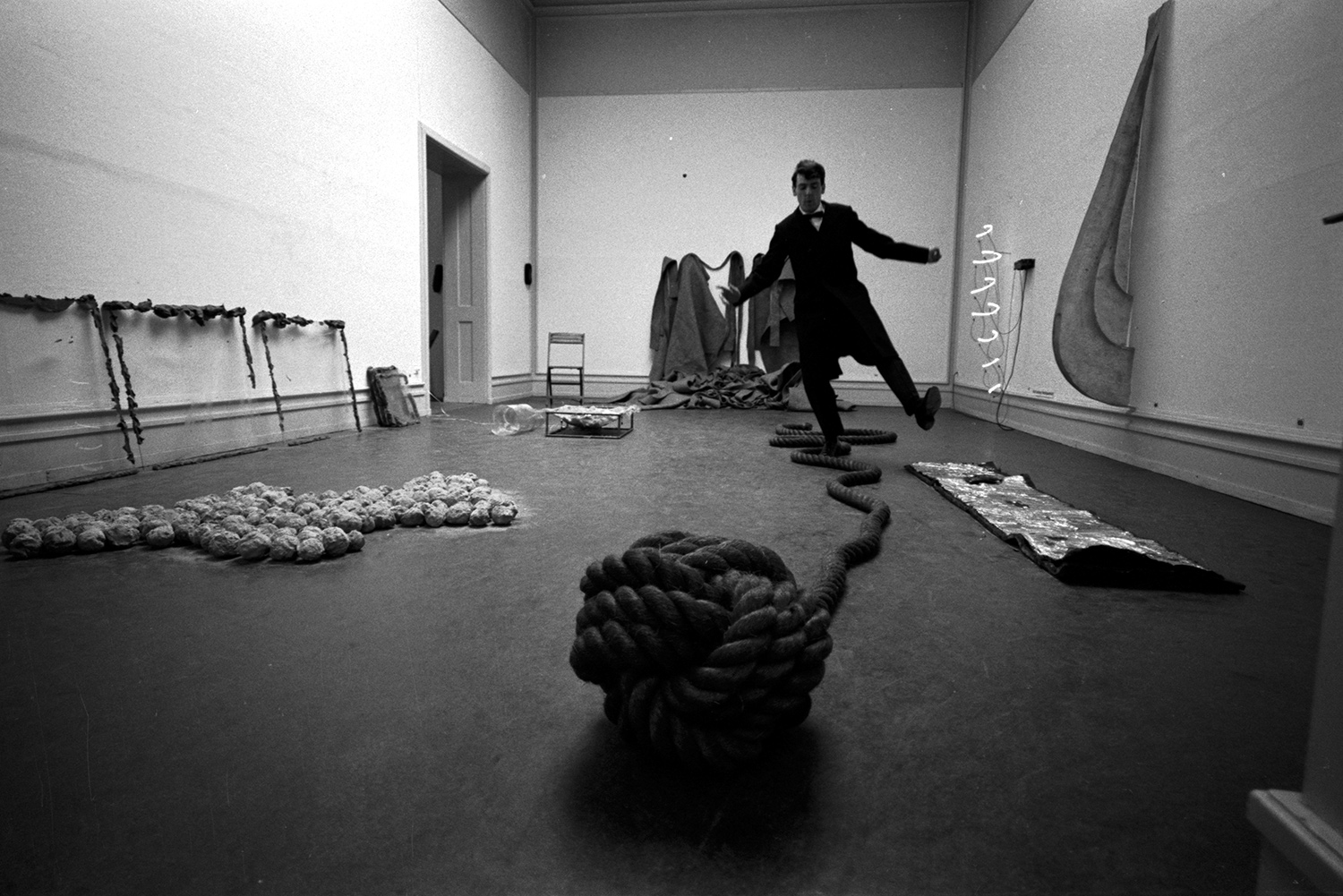

Celant laid these foundations from his first exhibition. The use of humble materials directly sourced from everyday life or nature, the unapologetic lack of formalism, the organization of the works in the space, and their processual aspect established founding principles for the era, in addition to introducing Arte Povera. Pavimento, tautologia (1967) by Luciano Fabro resulted from an azione that consisted in cleaning and waxing the floor before covering it with newspapers, in a humble gesture from the everyday life of 1960s Italy.3 1 metro cubo di terra and 2 metri cubi di terra (both 1967) by Pino Pascali seem to be made of an organic material (earth), and, like 32 mq di mare circa (1967),4 anticipate many off-site works of Earth art. Untitled by Jannis Kounellis exhibits coal, a poor material inscribed in the working-class memory, inserted into an industrial-type metal structure, etc. Their distribution within the exhibition revolves around the exploration of the extension modalities of non-sculptural works in space.5 The aim was to compel a different relationship between the viewer and the work, and to free it from its objectal confinement.

The centrality of the notion of attitude also appeared as early as the Genoa exhibition. For its catalogue,6 Celant wrote the critical text that contained the first instance of the syntagm arte povera, intrinsically linked to notions of banality, everyday life, and attitude, which were later placed at the center of post-minimalist conceptual art theorization: “What is happening? Banality is entering the arena of art. The insignificant is coming into being or, rather, it is beginning to impose itself. Physical presence and behavior have themselves become art.”

In November 1967, Celant published in Flash Art the manifesto-text “Arte Povera. Appunti per una guerriglia,”7 which is usually reduced to its strict political dimension. A detailed analysis shows that it also laid the foundations of post-minimalist conceptual art. Running counter to Sol LeWitt’s statement that “the idea becomes a machine that makes the art,”8 Celant’s conception is that attitudes are embodied in works, and constitute the tool that makes it possible to invent a “new art” antagonistic to the fetishization of the object. The whole text revolves around this pivotal concept, which comes up seven times, and also around the notion of behavior — totaling twelve instances within the article. Celant makes Marcel Duchamp’s chess tropism the emblem of an “anti-system” attitude that he places at the foundation of this “new art.” In contrast to the “rich attitude” based on the “market,” the “poor attitude” revolves around “research” and the “identification of the individual with his actions” and “behaviors.”

At that time, the aim of this definition of what could be a “poor art” was not to define an artistic movement, but rather to construct a critical category.9 This was why it proved to be operational across boundaries.

The article was followed a few months later by Celant’s exhibition at Galleria de’ Foscherari, whose catalogue was along the same lines.10 The intensity and breadth of the debates and political fights that developed around the very notion of Arte Povera — as shown by their transcription into a special Quaderno of Galleria de’ Foscherari, La povertà dell’arte, published in September 1968 — hindered the understanding of its theoretical and artistic importance.

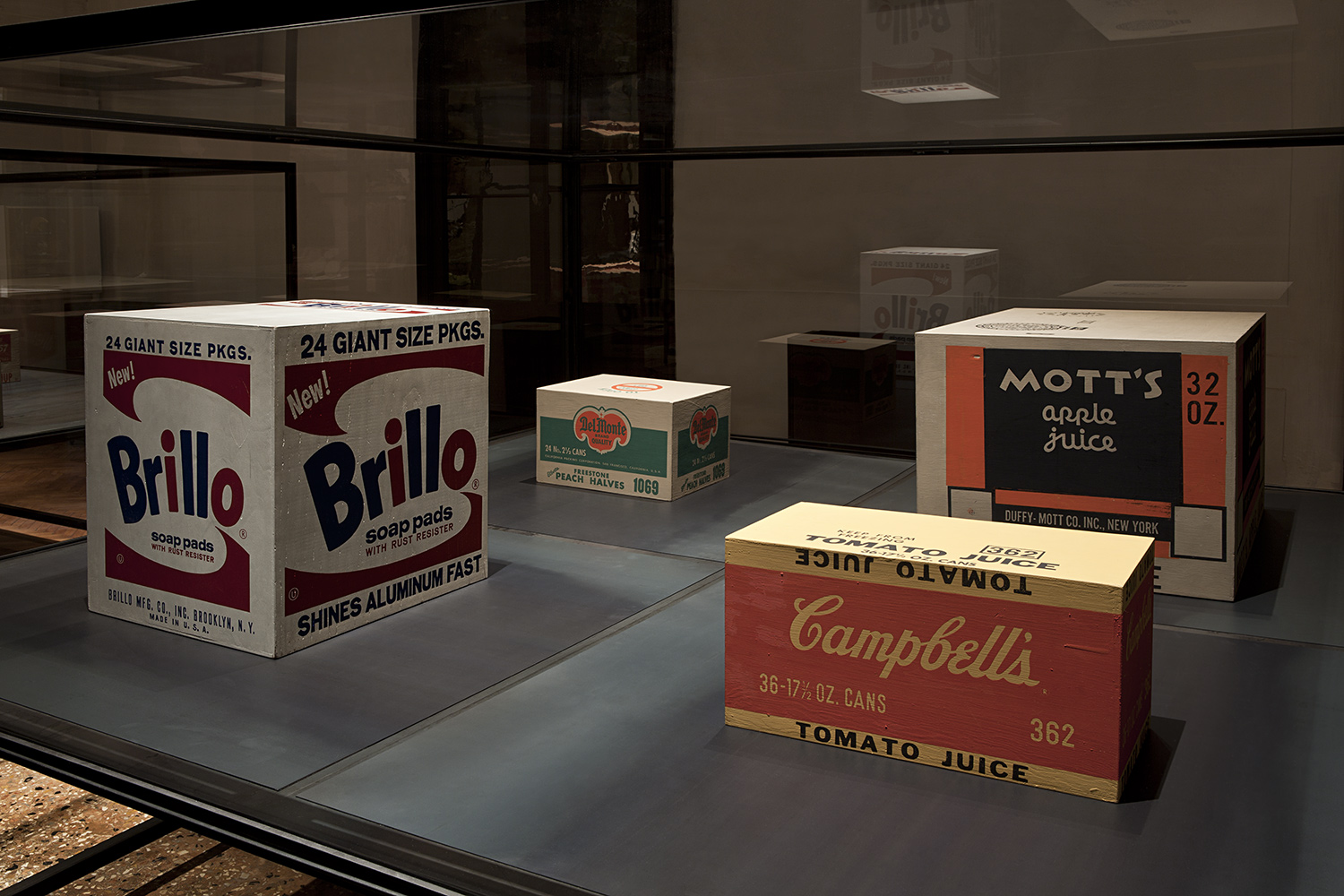

In fact, this paradigmatic notion innervated the whole conceptual art field. Flash Art magazine, along with a few critics, artists, and curators, like Piero Gilardi and Jan Dibbets, played an important role in its dissemination throughout Europe and the United States. In 1966 and 1967, the works of Robert Smithson and Robert Morris were still Minimalist. Work display modalities were still at least partly traditional even in the United States. For example, Dwan Gallery still showed most works on plinths or on the wall. Morris created his first Felt Piece, Untitled (lost) in 1968. He introduced the notion of “anti-form”11 in April, six months after the publication of Celant’s article in Flash Art. Nancy Spector has also pointed out that “Richard Serra created Belts (1966) shortly after returning from a year of study in Italy, where he undoubtedly witnessed the very beginnings of Arte Povera. Like the artists who would come to be associated with that movement, Serra employed nontraditional materials in his sculpture.”12 The off-site earthworks that Pascali and Gilardi’s works thematically or formally prefigured appeared after the exhibition and Gilardi’s journey to the United States. “Prospect 68”13 seemed innovative, but most of its specificities had already been implemented by Celant and the artists of Arte Povera in 1966–67.

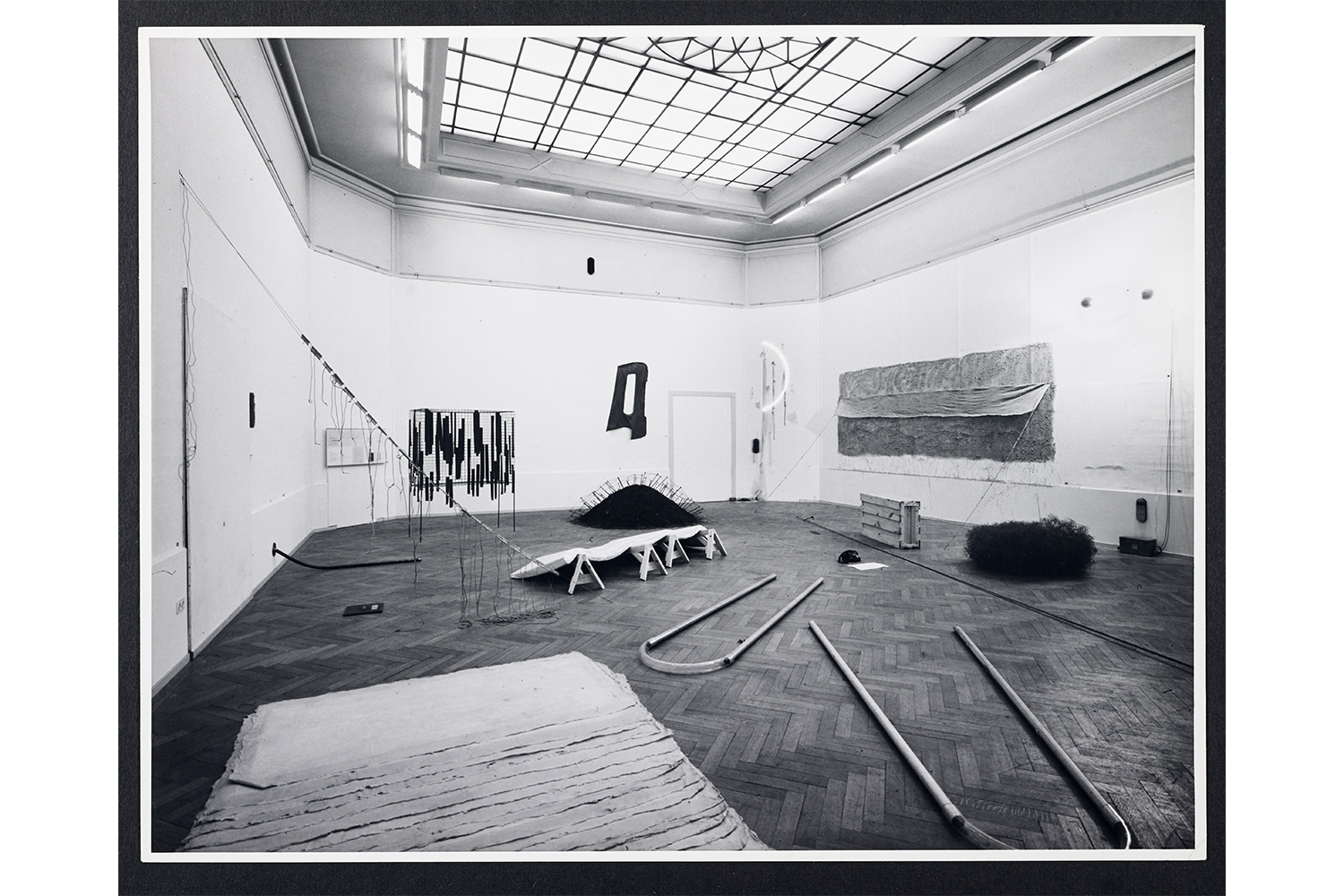

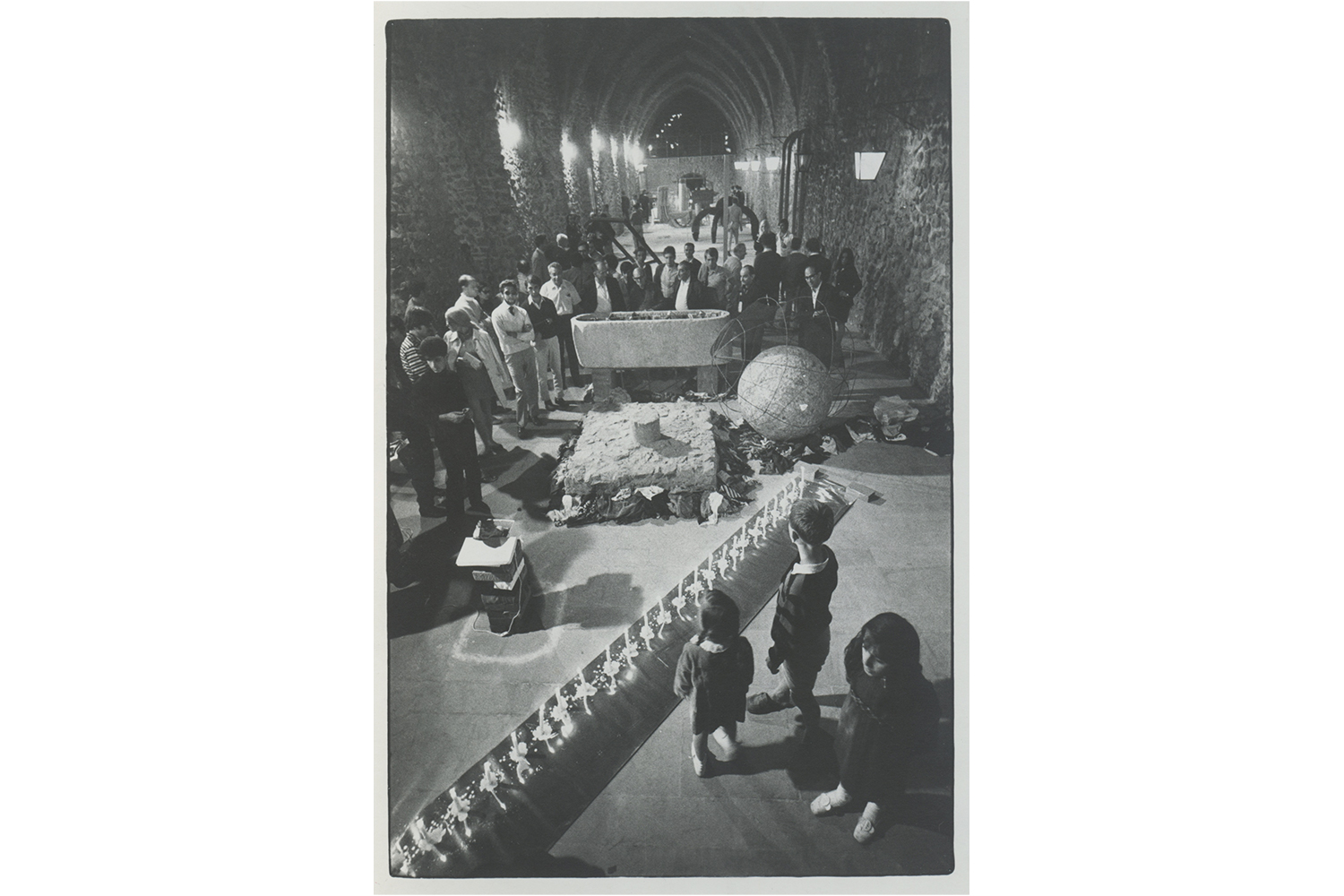

“Arte Povera più Azioni Povere” was held in the Antichi Arsenali di Amalfi and surrounding area in October 1968. The exhibition included works by Arte Povera artists, but also by Richard Long, Jan Dibbets, and Ger van Elk, whom Gilardi brought to Celant’s attention. From a formal point of view, the exhibition was similar to the one in Genoa. The use of floor space and the play with this were accentuated and erected into curatorial principles, the works including processual elements. But interventions on the building were planned, and azioni povere were intended — according to the program set out by Celant in Flash Art and in an article published in the Quaderno of Galleria de’ Foscherari — as an exploration of ways of going beyond the object’s fetishized place. The whole exhibition stressed concepts of process and attitude. As was later partly the case at the Kunsthalle Bern, the artists were invited to create their works in situ, often collectively, in line with a program that rejected “competition.” Artists, critics, and curators met as part of “Encounters,” held during the festival.

The Amalfi exhibition established the foundations of major post-minimalist conceptual art exhibitions in Europe and the United States,14 and constituted their premises. Let us look at the example of the most emblematic of these exhibitions, “When Attitudes Become Form.” The exhibition journal15 that Harald Szeemann started on July 13, 1968, shows that he paid very close attention to the Amalfi exhibition, which Dibbets had told him about in the summer of 1968. His encounter with Dibbets on July 22 radically transformed his exhibition project. Officially due to “chance,” it made him discover “actions” based on everyday gestures: it is nevertheless likely that Szeemann already had knowledge of Celant’s writings and exhibitions. Dibbets informed him that Long, van Elk, and Gilardi would be in Amalfi, and that they were working according to the same modalities. “That same day, I inform my colleague Edy de Wilde16 I plan to exhibit this ‘new art’ instead of the new experiments with light,” Szeemann noted.

He was an indirect and attentive observer of “Arte Povera più Azioni Povere.” In October 1968, he noted that he was planning to meet Dibbets and van Elk to discuss this subject on November 19. In fact, he had communicated with them several times on the subject before that date. The meeting on the 19th took place at van Elk’s home. Boezem and Piero Gilardi participated as well.

Szeemann then traveled throughout the United States in December 1968. On the 18th, he noted that the title “When Attitudes Become Form” emerged from a discussion with the exhibition sponsor. On the same date, after a conversation with Carl Andre and Sol LeWitt, he wondered: “Should attitudes only result in soft forms?” — thus borrowing elements of Celant’s critical thought. Again the same day, he noted: “‘When Attitudes Become Form’ — this has always been the case, of course, but the process has never been demonstrated so directly.”

In January 1969, he traveled around Italy, where he made contact with most of the artists of Arte Povera through Gilardi.17 He crossed paths with Germano Celant several times.

The Amalfi exhibition was followed by the eponymous catalogue published by Marcello Rumma in early 1969. It has been well documented that this publication was quickly followed by another, also edited by Germano Celant, called Art Povera [sic], published by Gabriele Mazzotta. Planned for simultaneous release in Italy, Germany, the United States, and the United Kingdom in March 1969, it explores the work of conceptual artists from different countries, almost all of whose work would appear in the Bern exhibition. But during a visit to his publisher, Celant met Harald Szeemann, who noted on January 9, 1969: “6:00 p.m.: Visit with the publisher Mazzotta. He’s doing a book on Arte Povera and holds onto my photos for the time being. The book title is an issue. They want to use mine: Quando attitudini diventano forma (opera, concetti, processi, situazioni, informazione).” Following this conversation, the publication of the book was delayed until November 1969, after the Bern exhibition.

On January 22, 1969, Szeemann wrote to Celant: “I wanted to ask you today if you would like to give the inauguration speech in Bern on March 22. The task shouldn’t be too difficult after having written the text for Mazzotta.”18

This written proposal, which was made after Szeemann’s break with Gilardi, would seem to constitute recognition of Germano Celant’s underlying importance for the exhibition. The artists of Arte Povera held a prominent place within the exhibition, accounting for eight out of the sixty-nine artists, or nine if one counts Prini, or twelve with Long, Dibbets, and van Elk. Anselmo, Boetti, and Merz presented four works each: out of the hundred and twenty-seven works in the exhibition, twenty-seven were by artists exhibited in Amalfi. Their real importance extended much further, and their place there appeared to be essential. Io che prendo il sole a Torino il 19 gennaio 1969 (1969) by Boetti, and Acqua scivola (Igloo di vetro) (1969) by Merz, became emblematic of it.

The distribution in the space, the spotlight on processual aspects, the importance of performative works, the “collaboration” between artists, critics, and curators, and the revolving of the exhibition around the notion of attitude, confirmed the anticipatory role played by Celant and the Amalfi exhibition.

Szeemann’s text for the catalogue partially took up the structure and reasoning of Celant’s article in Flash Art, which he augmented and amplified. Basing his argument on the tutelary figure of Duchamp, he placed the concept of “attitude” at the center of the exhibition, as one might gather from his choice of title. He took up many other key elements of the article. He characterized the exhibition as a whole using words that Celant applied to the concept of arte povera: “The displacement of interest from the result towards the process, the use of ‘poor’ materials, interaction between the work and the materials, Earth as a work material.” Also: “The artist’s activity as a human being is now the main subject.” “The title of the exhibition […] must be understood thus: never before has the artist’s inner attitude become a work in such a direct way.” He preserved Celant’s analysis of the rejection of the object in favor of attitude: “The artists in this exhibition are not object makers. […] They seek freedom beginning with the object, and add its processual dimension to its various strata of meaning. They want this processual dimension to be visible in the work itself, and in the ‘exhibition.’”

This reinterpretation leads one to wonder if Germano Celant’s reenactment of “When Attitudes Become Form” in 2013 (“When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013,” Fondazione Prada, Ca’ Corner della Regina, Venice, June 1 – November 3, 2013), beyond its historiographical and curatorial importance, should be understood as a dual historical mise en abyme. This meticulous reconstruction, necessitating several years of “archaeological” research,19 made it possible to revisit the initial exhibition; and forty years after “Ambiente/Arte, dal futurismo alla body art” (Italian Pavilion, 37th Venice Biennale, 1976), it led Celant to reconsider the theory and practice of exhibition reenactment,20 which he now viewed as readymades that could be reactivated or displaced.21 But the systematic use of the notions of displacement and reinterpretation, and his repeated references to his own historical role in the Bern exhibition during the interviews he gave at the time,22 lead one to wonder if these should be seen as clues calling for a reconsideration of the Ca’ Corner exhibition as also containing a final, and perhaps involuntary, reversal of meaning: a reinterpretation of the reinterpretation.

Analysis of other major exhibitions of post-minimalist conceptual art, like “Op Losse Schroeven” or “Earthworks,”23 goes along the same lines. It is therefore striking to consider — on a chronological, programmatic, theoretical, and curatorial level — the anticipatory role played by Germano Celant and, more broadly, by the artists of Arte Povera. A systematic and detailed analysis leads to a reversal of some of the statements and mythologies of that period, in a new perspective that proves to be heuristically fruitful. It also makes it possible to question the conception of Arte Povera as constituting only a subcategory of a broader international trend, and shows that, on the contrary, it should be seen as a paradigmatic notion that, hinging on the notion of attitude from the time of Celant’s first writings, permeated the whole of post-minimalist conceptual art, making this critical category both more intelligible and more homogeneous. Art historian Giuliano Sergio has highlighted Germano Celant’s “anticipatory role”24 in the evolution of the formal aspect of exhibition catalogues and his use of photography: in fact, it is to his practice as a whole that one can apply this paradigm, as the results of this research show.