Philippe Vergne: You conceive environments made out of what could be perceived as detritus, leftovers… or material “without qualities.” It ranges from sticks, plywood, garbage bags, hollow core doors, carpet… These constitute a complex vocabulary that, whether you (or me) want it or not, put a smile on a viewer’s face. It could be a smile of discomfort or a smile of complicity with your aesthetic program. I do believe that there is a provocative dimension in your work as well as a very classical attempt. Before we enter this, I am just curious to better understand what first attracted you to these materials?

Gedi Sibony: I have two clear memories from the early days of my first studio. One is a hollow core wooden door that I’d been using as a table was too long so I cut it shorter, and the other is four pieces of squarish MDF that I screwed together to use as a pretty wonky step stool. Over the next few years they both were incorporated as objects and ended up as elements in my first show. The step stool had functioned for me in so many different ways. Married to a group of sticks, I had balanced it by gluing it together and, dirty from use, it triggered a question. I felt somewhat defiant in honoring that thing at the moment it surprised me. It felt partly slapstick and flirtatious too. And it triggered follow-up moves. I also wanted soft, blank, clean things. I fell in love with one particular lightweight gray carpet. It took up space and was empty. The doors seemed to work that way too, easy to transport, leaned upright, had a good size. As spatial markers or pauses they could divert or direct attention, shifting momentum in a room. To some degree I felt the materials and the places as already made for each other.

PV: You mentioned shifting momentum in the room. Are your concerns mainly formal or mainly philosophical? Or both? Or is the question itself absolutely irrelevant because you do not fall in these categorizations?

GS: My approach is pretty informal. I’m indulging in the way things are articulated, the fabric of narrative. In my case it’s a process of compensations. I’m looking at every situation specifically, all the personal exchanges, expectations, the feeling and nature of the space, in order to direct a process of unfolding. And that happens within the structure of my own communicative disposition. So by shifting momentum I mean visually but also emotionally. Tuck things away, set up decoys, block sight lines or be straightforward. The pleasure’s in the process of deciphering this range of aspects concisely.

PV: When you were installing your room for the Whitney Biennial you told me one day that you wanted the elements, the objects in the room to be “lovable.” What did you mean by that?

GS: I thought you said you wouldn’t tell anyone.

PV: Well, what cannot be conceived clearly should not be talked about. Very Wittgenstein of you. So no, I won’t talk about it. Your background, if memory serves, is not in art but in semiotics. How does this background structure or affect your work?

GS: My education was very analytical, and I was encouraged to feel comfortable inside my own head. I found I was reluctant to really touch — in painting I was very tight and structured. Going into semiotics was a default. It probably left some imprint, but I lost interest and needed to move, physically, and became involved in Capoeira. In this Afro-Brazilian martial art, developed in the skin of a dance, there is a relatively small index of moves, enacted between two players, improvisationally, around a very basic structure. The Angolan style is slow and full of subtle shifts. Deeply expressive gestures are reduced to suggestion. As you learn the language, you see the humor, the individual personality traits emerge in relation to each other. Intelligence manifests in anticipation and its ability to shift course at any given moment due to circumstances.

PV: Do the materials you use constitute a defined language with syntax and elements of vocabulary? If so, what are they and what do they stand for?

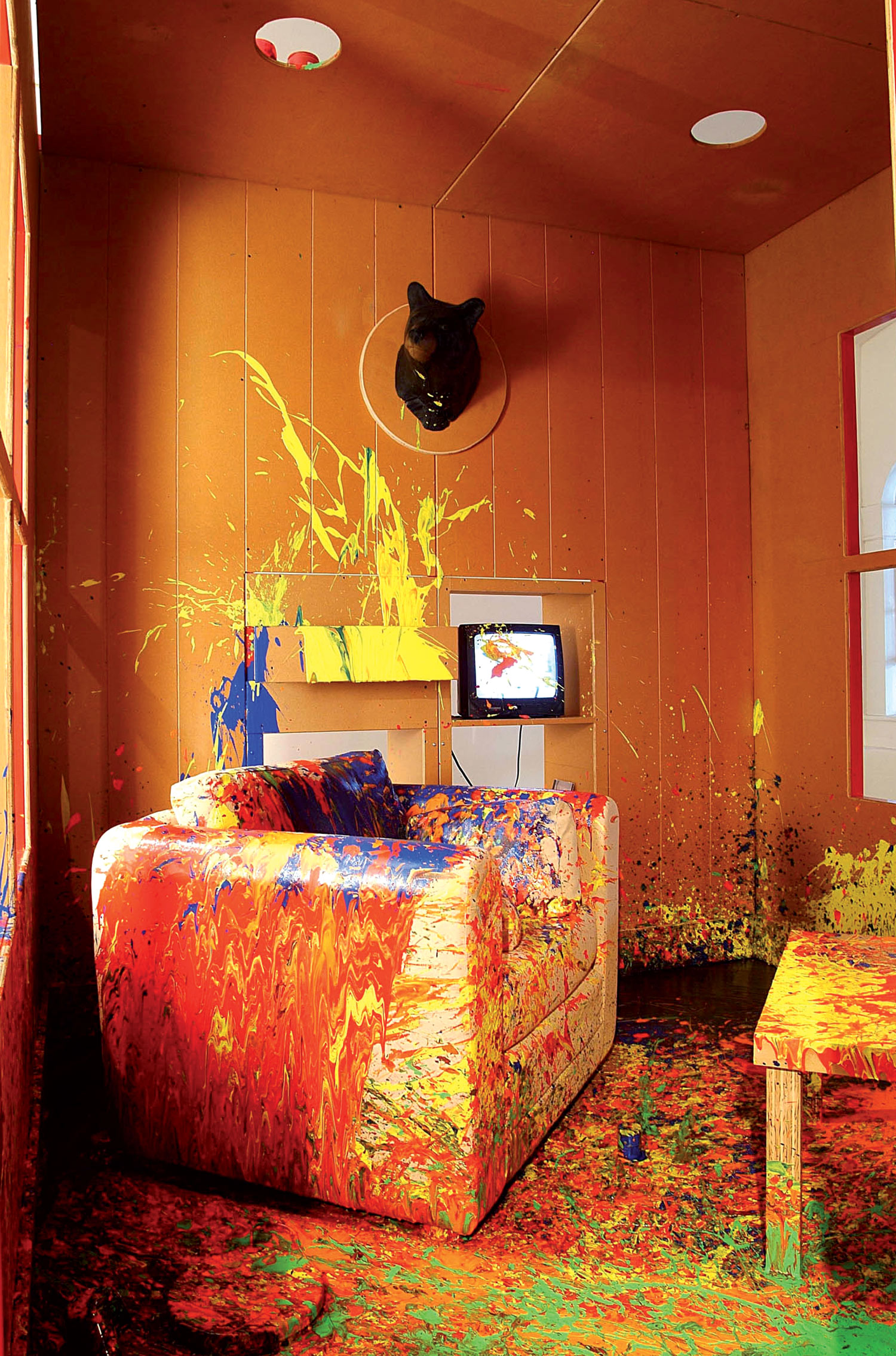

GS: Yeah, this is the most exciting part to me. There is a drama being conducted in all these different rooms and all these different buildings. For example, I cut a contractor bag to cover the surface of a door that was overworked because I didn’t want to look at it anymore. Then I draped the cut-off remains over a basic plywood post and lintel structure I had previously glued together. At the moment I didn’t think much of either thing but they grew on me. The door went to P.S.1 and the draped scrap ended up going to the Whitney Biennial. Two parts cut from the same cloth, entering the world in different costumes with different attitudes and different roles to play. The vocabulary is expanding. Different combinations, new materials yield different affects. What they stand for also shifts. I see it as note taking.

PV: This afternoon, during the talk with Adam Weinberg, you mentioned that you think of your work as drawing. Could you elaborate on this?

GS: Drawing feels active. It has a wing. It can spin out of control, progress unhinged, and still land on its feet, like Buster Keaton. Sculpture, on the other hand, tries to capture too much and sits on its own in the face of the interconnectedness of things.

PV: During the talk and once in the studio, you said that through your work you are attempting to reduce the distance between you and the world around you. For which purpose? Is your aesthetic program humanistic?

GS: In a way my language is esoteric, but it doesn’t make any demands. There is no scripted meaning or “getting it.” My mother-in-law told me it reminded her of the space of waking up. She described feeling an anxiety in leaving dreams for the fog of consciousness, but on waking up there is a realization everything is OK. That seems like an important space. In my experience, distance is ideology. It’s trying to know something from above, separating, losing sight for some idea. That’s how men are taught to survive. My son is going through this phase where he’s developing mind-space, beginning to sense that motivation lies behind action, and he’s looking to me and his mom to figure out what to feel in the face of new experiences. I feel the same responsibilities as an artist. If nothing else I’m at least trying to share my own experience as I perceive it.

PV: You explained to me that the ancient Chinese expression for the mechanics of everything was “the ten thousand things.” We are in the art community surrounded by ten thousand things and very often nothing. But thingness seems to be the rule. Nothingness seems to be part of the ethos of your work. Or “almost nothingness,” “close to nothingness,” maybe in a Zen Buddhist way. I mentioned before a provocative dimension about your work. Is it tongue in cheek?

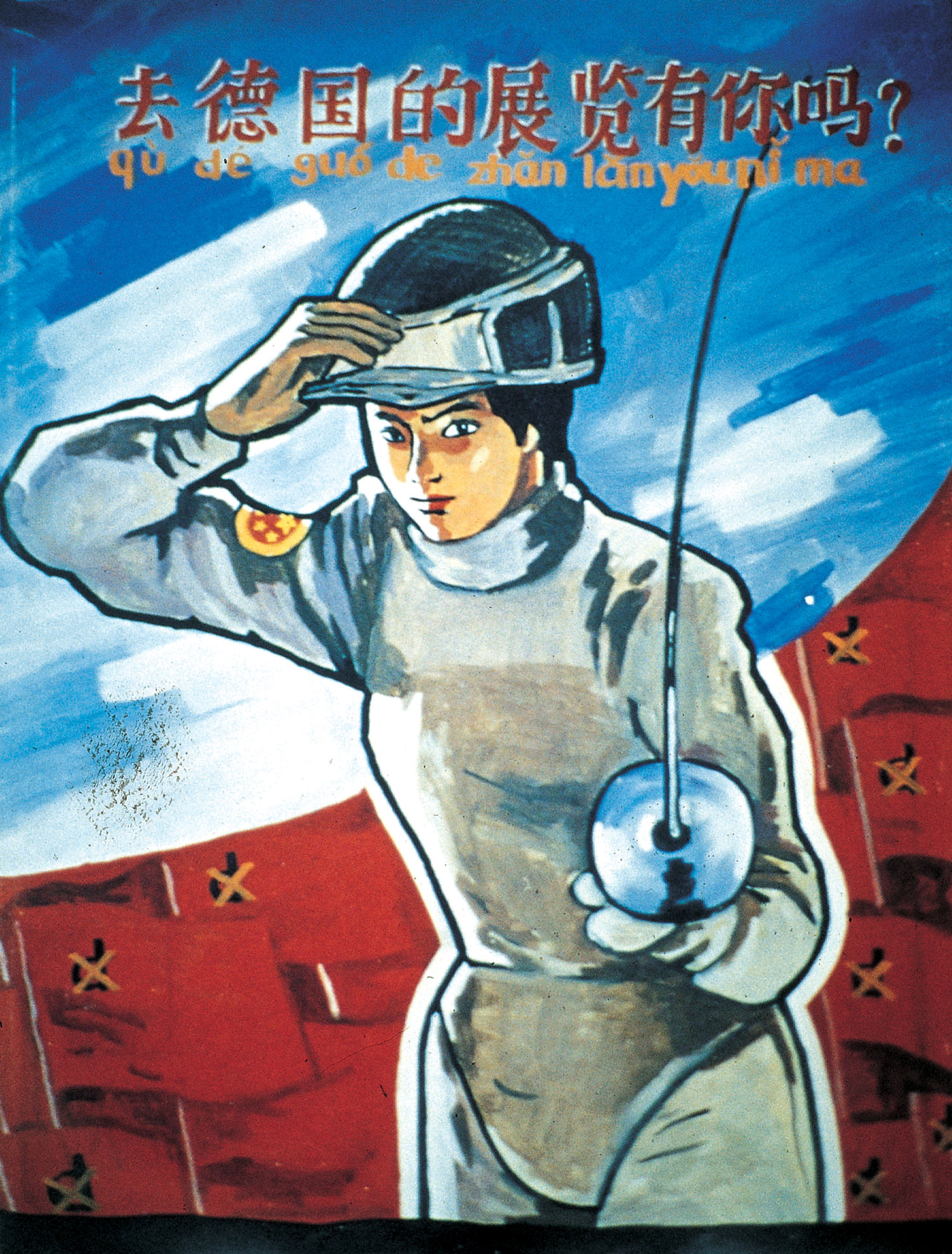

GS: I first came across “the ten thousand things” reading the Chinese philosopher Chuang Tzu, which is full of loopy anecdotes, non-sequitors and ridiculous, flat-footed humor. Language is used as a chisel to break down assumptions: silly and serious keep changing sides. So you ask if the provocation is tongue in cheek. I see that in your work too — in the way that you and Chrissie [Iles] used things to serve some affect. At the Whitney I took my cues from the two of you. In general I get distracted and hindered by things—I’m always tripping over them. But I know they make space possible, so I use them too, almost reluctantly.

PV: When you look at one of your sculptures or environments, how do you know it is done?

GS: When time runs out.