Gardar Eide Einarsson: Perhaps we could start by talking a bit about form: It seems to me that some artists of our generation are developing a practice that could border on formalism. I think in your work, the work of Oscar Tuazon and to some degree in my own work, there is the sense that artists who come from a rather rigorous critical and conceptual background where enjoyment in form was quite frowned upon are now allowing form take center stage. What I find interesting in this take on “formalism” is that the work is still able to retain its critical heritage.

Matias Faldbakken: I guess we have quite different approaches to this, but one common trait could be that you, Oscar and I have practices where a “parody” of the formal is never far away. At the same time the insistence on the physical presence of the work, the quantity of the output and the possibility of an aesthetic precision might gain enough authority for these “comedic” aspects to constantly be destabilized or overruled. This could also be true for, say, Josh Smith or other artists who clearly have a program that constantly bleeds through the largely formal appearance of the work.

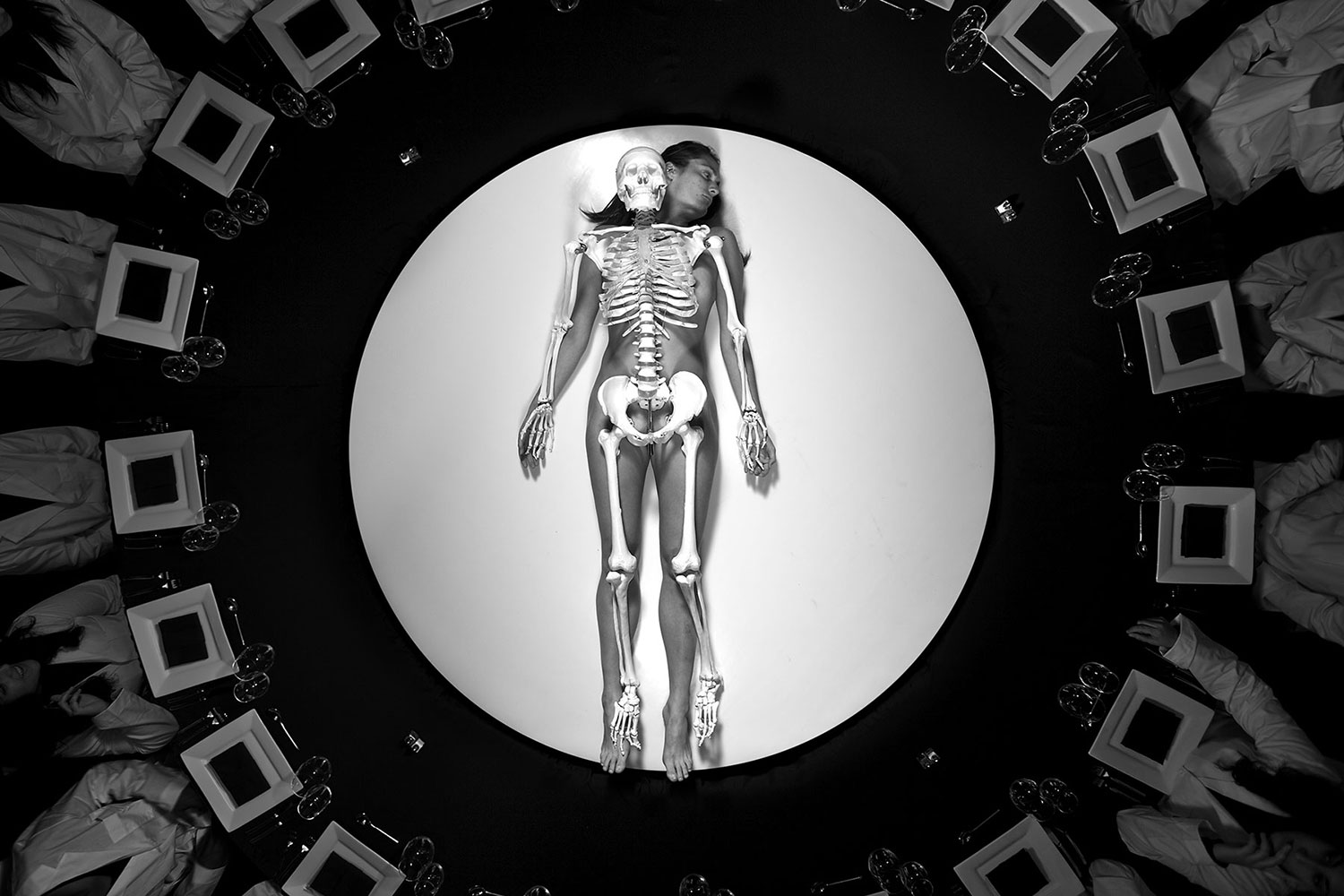

GEE: I like this idea of a parody that keeps slipping. It reminds me of the classic plotline of the undercover cop who spends too much time undercover and loses his clarity of conviction, sympathizing too much with the outlaws he has surrounded himself with and initially only pretended to befriend. This character then ends up no longer blindly doing his superiors’ bidding, what in the parlance is know as “going rogue.” In my case my relationship to painting is definitely mainly critical, perhaps parodic. I have seen (and mainly still see) my paintings as props or stand-ins for paintings, a form of zombie half-life paintings — a necromancy of painting as opposed to Steven Parrino’s necrophilia with painting. But I am aware that the host body at some point started to fly back and the original intentions started to become impure and less total because of everyday life, infected perhaps by a serene relationship to certain painting concerns.

MF: The Donnie Brasco of painting? Where painting turns out to be the mobster and the critical interest is the cop? Could it be that such an undercover operation also works as some sort of a refuge from the often cop-like characteristics of outspoken criticality?

GEE: Well, the rift between the undercover operative and his taskmasters is usually over the latter’s lack of ability to see beyond their own agenda and into the complex morality of the situation at hand. The ’60s, the era of the bone-dry critical artist, was of course also the era of the admonishment to “kill your inner cop.” I would like to point out though that what is necessary here is not only to kill one’s inner cop but also one’s inner child. As we know, “You never go full retard.”

MF: OK, the “form” we started out with is so far: parodic, outlaw, zombie, half-life, necro, host body, child and retard. Anything else?

MF: To speak for myself, parts of my practice have long revolved around the idea of resigning and the moment of resignation as a paradoxically potent moment. I’m trying to stick to that feeling of almost always resigning, if you know what I mean. One byproduct of this “strategy” or attitude is now and then to resort to a more muted, gestural, wordless, visual and at-the-end-of-the-day formal practice because it has the air of somehow being simultaneously doomed and potent.

I like that in-between quality. The half-life, the parody, the retard — they can be your allies too. (Or, as the zombie once said: “Great minds taste alike.”)

GEE: A sort of ascetic approach then, renouncing criticality and seeking refuge in the wilderness (or is it the leper colony) of form(alism)? But for it to make sense the form must present some sort of potential that cannot be fully had by applying only a critical/conceptual approach. Or is its potential purely that of escape and negation?

MF: Escape is always an important factor. But I’ve been thinking that there could be some potential in encrypting, in abstracting, in visibly shutting up, so to speak. And that this clamming up and semi-suppression of the (literal/critical) content in favor of some non-formalist “form” gives the critical and/or conceptual axiom of the work another kind of life. A not so obvious kind of life perhaps. (A kind of no-life? As in: You cannot kill what has no life…)

GEE: I have long thought that one of the strong qualities of contemporary art is that it allows for this veiling or clouding, where the viewer is aware that there is information and interpretation that is not necessarily available to him or her. The viewers reaction of “There is no there there” is perhaps supplanted by “I know there is a there there but I just can’t quite seem to pin it down.” Not having to ingratiate yourself to the viewer in the way that many other forms of popular culture require allows for the possibility of quite subtle arguments and a more autonomous production of meaning. As in most subcultural formation, access is granted in exchange for time spent and effort put into understanding. Ideally for me the production of work is a dialogue that evolves over a long period of time (spanning many works, shows, books, etc.) where information is revealed — and sometimes confused again. This is perhaps where the form becomes subservient again to a critical project?

MF: I totally agree. Not having to ingratiate yourself to the viewer is a key issue. And a perhaps related aspect is the intrinsic user-unfriendliness that is given space in the institutions of contemporary art; its somehow limited populist potential. There certainly are various “blockbuster” practices that draw crowds and (media) attention, but they are, in my opinion, rarely the most interesting ones. I feel there is often some kind of disappointment connected to the reception of art. Confusion, as you say. This disappointment is vital. Art seems from time to time to mediate that its own mediation is never really fulfilled or that it is even untrustworthy. The more persuasive qualities that are identified with literature, music or film are often absent in art, and that could very well be one of the qualities (or lack of qualities?) that keeps visual art unresolved — in a good way. In relation to other artistic categories I am very interested in “blockbusterism” — the tapping into the popular mind — but when it comes to art it’s the other way around. That art doesn’t make sense in the same way as other popular practices.

GEE: There is absolutely a patience with interpretative labor on the part of both mediators and audience in the art world that one would be hard pressed to find in other arenas of cultural production. I wonder too if this is connected to something we have both been interested in and working on over the years, namely the low-tech circumstances of art production. Even though a museum like Tate is expensive to build and run, and they need a certain number of visitors to make it go round; for Gerhard Richter to paint a painting is not expensive at all and pretty much requires only one guy, a roof over his head and materials that would be affordable to almost anyone. The finished art piece would also have basically the same effect whether it was shown in a billion dollar museum or a temporary storefront space — it might look (and become) more expensive in the museum, but as for its conceptual meaning in relation to painting it would work in either space. The same would be true for most contemporary (and I guess also historical) art. If we take our own work as an example, the fundamental framework of how either of our production happens seems not to have really changed since we started making art and would remain possible irrespective of economic circumstance.

MF: Yes, but it’s still very dependent on the institutional framework to retain that conceptual meaning. I play a lot with the somewhat confusing idea of value and the notion of the “pricelessness” of artworks in my own production. Many of the works that I make would not be recognizable as art as soon as you carry them out the gallery door. My so-called object production wouldn’t make much sense anywhere else, and the objects would in some cases even disappear in the wrong context. Brown packing tape… This also underlines that the conceptual premise of the work is perhaps the most stable aspect; that both the form and physicality is somehow temporary. Or exchangeable.

GEE: Yes, Marcel, but your work is still recognizable as art as long as it is within the conceptual framework of the art institution. The works are recognizable as artworks to an art crowd. Your sculptures would still have their communicative potential intact in an ad hoc space as long as the art world agreed that it was an art space. Once a collector has carried the Faldbakken sculpture he just bought it is still recognizable as a Faldbakken sculpture to his collector buddy (Aha! Packing tape!) — just not to the guy manning the local kebab stand. I too feel like there is a lot of potential in this alternative — and to some extent covert — sign register. I like the return to the meaning (or lack thereof) of form where the form here again is parodic or allegorical. A formalism where the form is exchangeable is quite good I think.

MF: Ha ha, everyone’s a critic. Well I wasn’t thinking too much about the classic readymade aspect here, but rather that the objects “crafted” by me (or you?) (yes, often with “ready-made” materials) in the gallery or the kunsthalle would sort of evaporate to other places, no matter how recognizable within the premises of art. And that this gives the “form” we are talking about a weak and ephemeral quality. As you mention, these weak or vague forms can — seen over years, perhaps even spanning a full career — add up to become one big, solid narrative, critique, concept, complex of ideas… Or one epic gesture…? You are perhaps a bit more consistent when it comes to a recognizable style than me, though.

GEE: But hopefully that style is again to some extent parodic or at the very least self-aware. The weak form is good though; it feels as if the relationship to form is often about keeping it weak, keeping it balancing in between worlds and continuously making decisions aimed at trying to undermine said form.

MF: A dimming of the form? To pursue an art whose “twilight can last more than the totality of it’s day, because its death is precisely its inability to die”? Back to the zombie…

GEE: Ha ha, Agamben!