Since 1979, Ars Electronica has served as a platform for discourse surrounding the convergence of art and technology within society. Its yearly festival brings together media artists, activists, engineers and scientists to assess technology’s developing impact in order to effect meaningful social change. Its artistic director Gerfried Stocker has stressed that it isn’t technology per se that changes our world but how people use it, forecasting the next technological revolution as a mushrooming of social media into a situation of “smart” citizens within digital communities and post-cities. Here he outlines how machine learning –– coding computer programs to learn for themselves –– is changing the game.

Alex Estorick: The theme of the 2017 Ars Electronica Festival is “AI: The Other I.” How will the show frame the current debate about artificial intelligence, and how do you see that debate having evolved over the years since AI emerged as a scientific discipline in the 1950s?

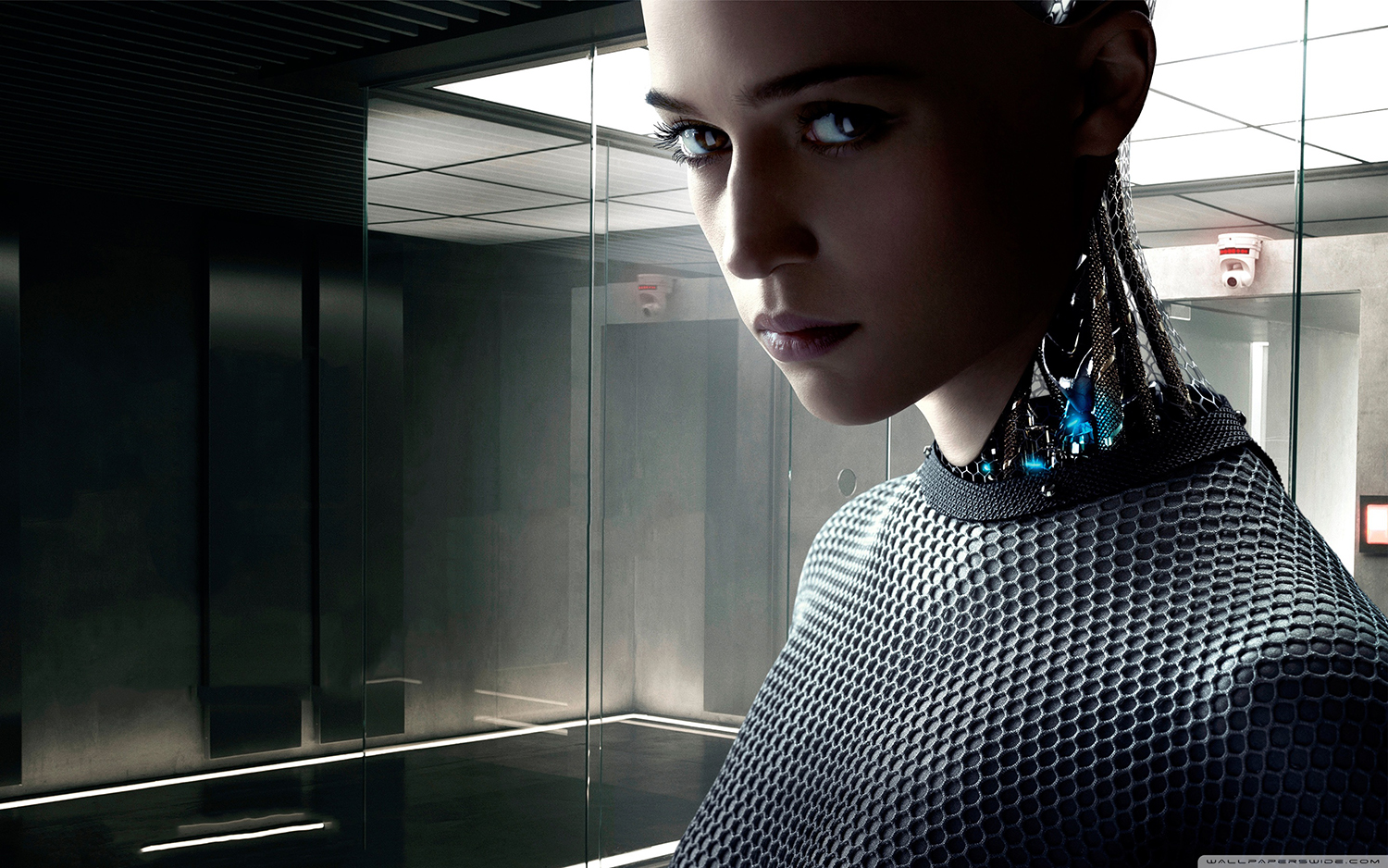

Gerfried Stocker: I think the second part of our title, “Das andere Ich” (The Other I), shows clearly that we are focusing on the cultural and philosophical questions stemming from present rapid developments in machine learning. Here we have this fascinating question of how we look at our self — the essence of being human. The festival includes an exhibition titled “Point Zero,” which divides artists’ responses according to: “Human.0” (What is the essence of being human?); “Machine.0” (What is the essence of being a machine?); and “Data.0” (What is the essence of being born from data?). But there will also be a comprehensive tutorial program suited to artists interested in working with machine learning.

As regards the developing debate around AI, recent advances in big data and machine learning are of course making a big difference from a technical and scientific standpoint. But with respect to our fears and fantasies almost nothing has changed, besides a growing critical awareness on the part of the media and wider public that ever more surveillance and control is fueling dystopian narratives. What is quite surprising is that the huge amount of new scientific knowledge gained over the last twenty years about brain functioning is hardly reflected in the discourse surrounding artificial brains. We mustn’t only consider the potential risk that in a hundred years machines will be outliving humans, but also focus on how we can avoid negative fallout from high-performance and autonomous control systems. We have lost our individual privacy to a great degree; we must now ask how we avoid losing our individual autonomy.

AE: Ars Electronica is based in Linz in Austria, a city with a very weighty history. Does this bring an urgency to your work in seeking socially inclusive technological solutions?

GS: I didn’t grow up in Linz, but from what I know the city has been one of those most responsible in dealing with the heritage of the terrible Nazi times. This is likely one reason why Linz has been so sensitive to the social relevance of new technologies. But I think it’s also important to recognize that the discussions about new technologies introduced by the Ars Electronica festivals have often been positioned as social and cultural challenges within an artistic frame, and not as purely technological or industrial issues. One important role of Ars Electronica has been to contribute to a more open and inclusive way of looking at new technologies.

AE: How do you understand the role of art-making in approaching AI? Do you think there is a fear of engaging with technology that marginalizes human intention within the creative process?

GS: No, in fact it seems to be the other way around. Many artists are interested in this challenge because it’s not simply an exploration of the technology but rather a journey to the origins of creativity. Reflecting on the tools we use in the artistic and creative process is something that has been very important in media art since the invention of photography; think of [Henry Fox] Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature (1844). With machine learning it becomes even more interesting.

AE: You’ve spoken recently about our increasingly liquid identities. How do you see AI modifying the debate about gender? Are there any strategies developed by artists that have particularly struck you?

GS: There are a number of artists currently considering the ways machine learning systems are replicating the cultural and gender biases in our society. This is due to how neuronal networks are being trained and is therefore technically unsurprising, though it leaves quite an impression to see our own biased value systems replicated in machines. When we think of how many decisions will be made by such systems in the near future, it’s clear that we mustn’t leave these developments up to engineers and private companies, but rather to consider them in relation to society as a whole.

AE: You’ve been critical of contemporary architectural practice for tending not to engage with digital modernity. How do you envisage AI as modifying our urban surroundings in the coming period?

GS: The first wave will be a dramatic increase in smart digital control systems which, without being significantly different, will have a dramatic effect. Of course there are numerous aspects of today’s urban infrastructure that need to be improved, but none of us can really envision the depth of transformation signaled by AI to the underlying structure of so-called smart cities. What is dangerous is that many things will still appear as they always have. The task for those working in architecture and design is that of expressing the difference between how, for example, simple traffic lights are currently controlled and how they are due to form part of a super-control (and therefore also surveillance) infrastructure. Even if they are to our benefit, we need to find ways to make these new systems and their impact legible.

AE: “AI engines” came to the fore in controlling the actions of characters within video games during the 1990s. How do you view contemporary art’s relationship with video games and Artificial Life (AL) software –– used to create characters for mainstream cinema?

GS: I like very much that “artificial stupidity” is almost as important for computer games as the “intelligence” of the algorithms behind the games’ characters. To keep games entertaining for users, developers have had to purposely implement flaws, failures and limitations within the performance of game engines. I think that there are really very few interesting crossovers between contemporary art and computer games, even though it has become very appealing to contemporary artists to use game engines and game characters in their work. That said, there is value in this kind of critical reflection on the cultural impact of computer games. I am personally more interested in how an artist’s viewpoint can contribute to new directions in gaming, digital narration and storytelling. A good example is David O’Reilly’s new work Everything (2017). Digital technologies have been important game changers in the visual creation of characters, and of course there is also motion tracking. The next frontier with AI will be storytelling itself.