Raymond Carver’s 1981 short story “Why Don’t You Dance?” centers on an anonymous grief-stricken and alcohol-soaked man who, in mourning his recent marriage separation, bizarrely reassembles the contents of his home on his front lawn. When a couple mistakes the setup for a garage sale, the man attempts to purge himself of his personal affects, offering discounts from where he reclines on a sofa in the grass, double-fisting whiskey and beer. It becomes clear that in divorcing himself from his house and belongings, the man is attempting to rid himself of that which shapes his identity.

“For a Dreamer of Houses” at the Dallas Museum of Art is an assembly of fifty-four works all culled from the museum’s collection, with ten being recent acquisitions. Citing its foundation in French philosopher Gaston Bachelard’s theory of the house as metaphor for mental and social development, the exhibition questions how domestic spaces and objects influence belonging, alienation, fantasy, gender, and the body: all themes again pertaining to identity formation.

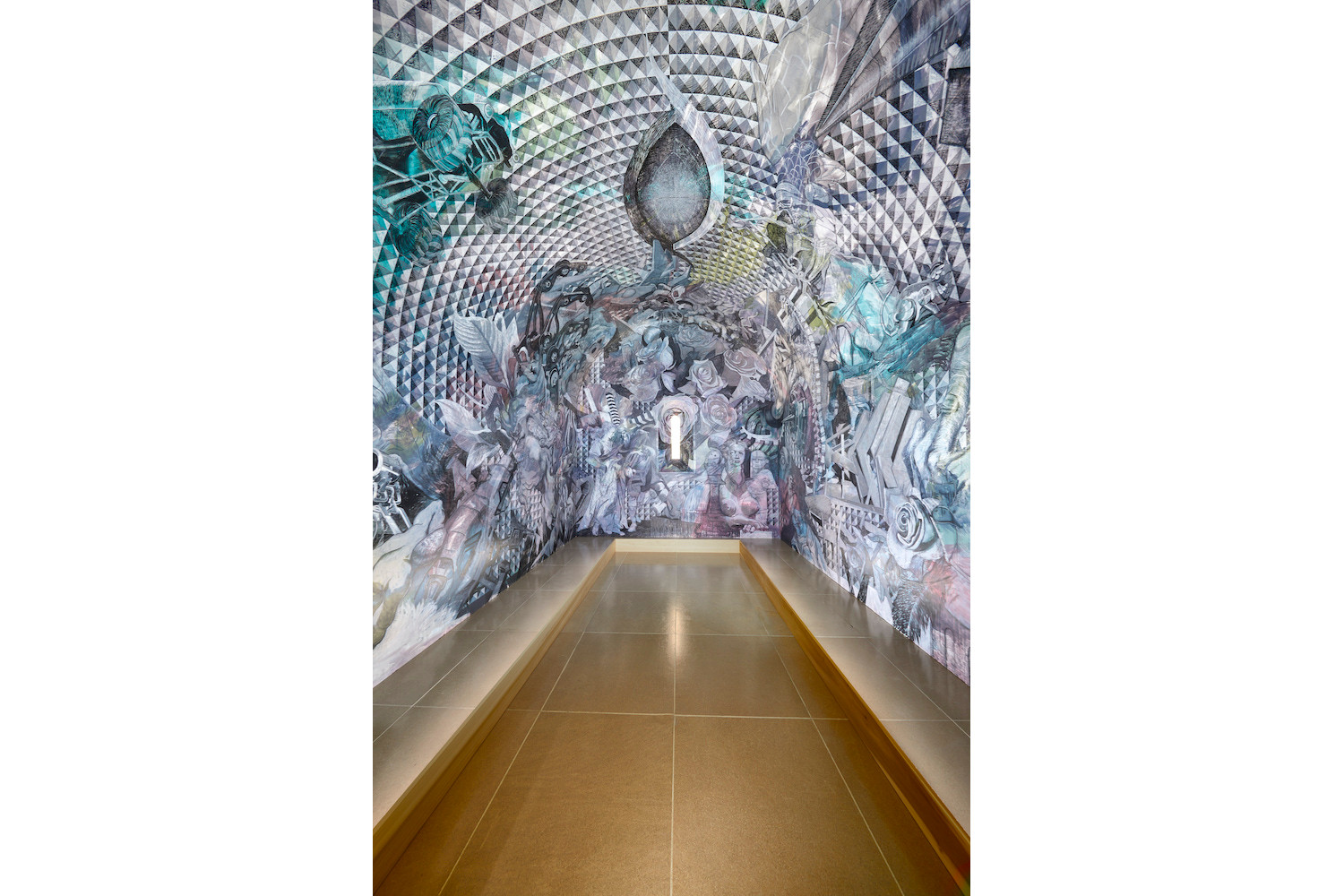

The strong relationship between the home and identity emerged in the nineteenth century following the decentralization of organized religion, at which point the “sacred” sphere shifted to the home, where “values of peace, protection, quiet, and nurture formed a domestic ideology and cult of childhood.”1 This thread between the church and home is evident in Francisco Moreno’s Chapel (2018), an immersive installation mimicking a chapel space, with an interior covered in intricate collage-like paintings reminiscent of frescoes from Renaissance and Baroque art history.

Another prominent work, Do Ho Suh’s Hub, 260-10 Sungbook-dong, Sungbook-ku, Seoul, Korea (2016) is a translucent structure that recreates architectural facets from the artist’s childhood home with polyester fabric and stainless steel. As with all of the nine works in Suh’s “Hubs” series, the installation’s meandering interior represents the increasingly messy line between public and private life, and the ongoing shifting of identity. Moreover, in the form of an eye-catching neon skeleton of a home’s frame, Alex Da Corte’s Rubber Devil Pencil (2018) also focuses on childhood experience within a domestic context. Screened on a loop inside is a three-hour video amalgamation of fifty-seven dreamlike film fragments taken by the artist and his assistants, which underscore iconography associated with childhood.

The legacy and significance of objects and materials shines here as well. A sparse section dedicated to domestic items is populated with three sculptures by Olivia Erlanger, Robert Pruitt, and Sarah Lucas; Erlanger, in particular, delights with Pergusa (2019) by marrying fantasy with the mundane via a scaly mermaid tail pouring out of a washing machine. Pruitt’s me and this mike is like yin and yang (2002) combines a vacuum, oversized doily, and microphone to celebrate the act of performing for one’s self in the privacy of the home.

Pipilotti Rist is also on view with 2010’s Massachusetts Chandelier, a colorful hanging sculpture made entirely of underwear, which evokes the abdomen as the original human “home.” Danh Vo’s Lot 20. Two Kennedy Administration Cabinet Room Chairs (2013) is a wall work displaying leather sourced from an upholstered chair that originally sat in John F. Kennedy’s cabinet room. Other works in the show include paintings, photographs, and works on paper by artists such as Jacob Lawrence, Clementine Hunter, Bill Owens, or Misty Keasler, which function like treasured ephemera.

I initially questioned the idea of “viewing” a virtual exhibition hinged on architecture, skeptical of the impact physical distance may have on a show so reliant upon the sculpturally immersive. Yet the role of the home in the ongoing development of identity is so tenderly at the forefront of “For a Dreamer of Houses” that the absence of imposing sculptures or installations does not detract from its poignancy. By exposing one’s home or belongings, one exposes parts of the self, and so the exhibition thereby remains successful, ultimately proving that constraints cannot dampen the power of memory and objecthood.