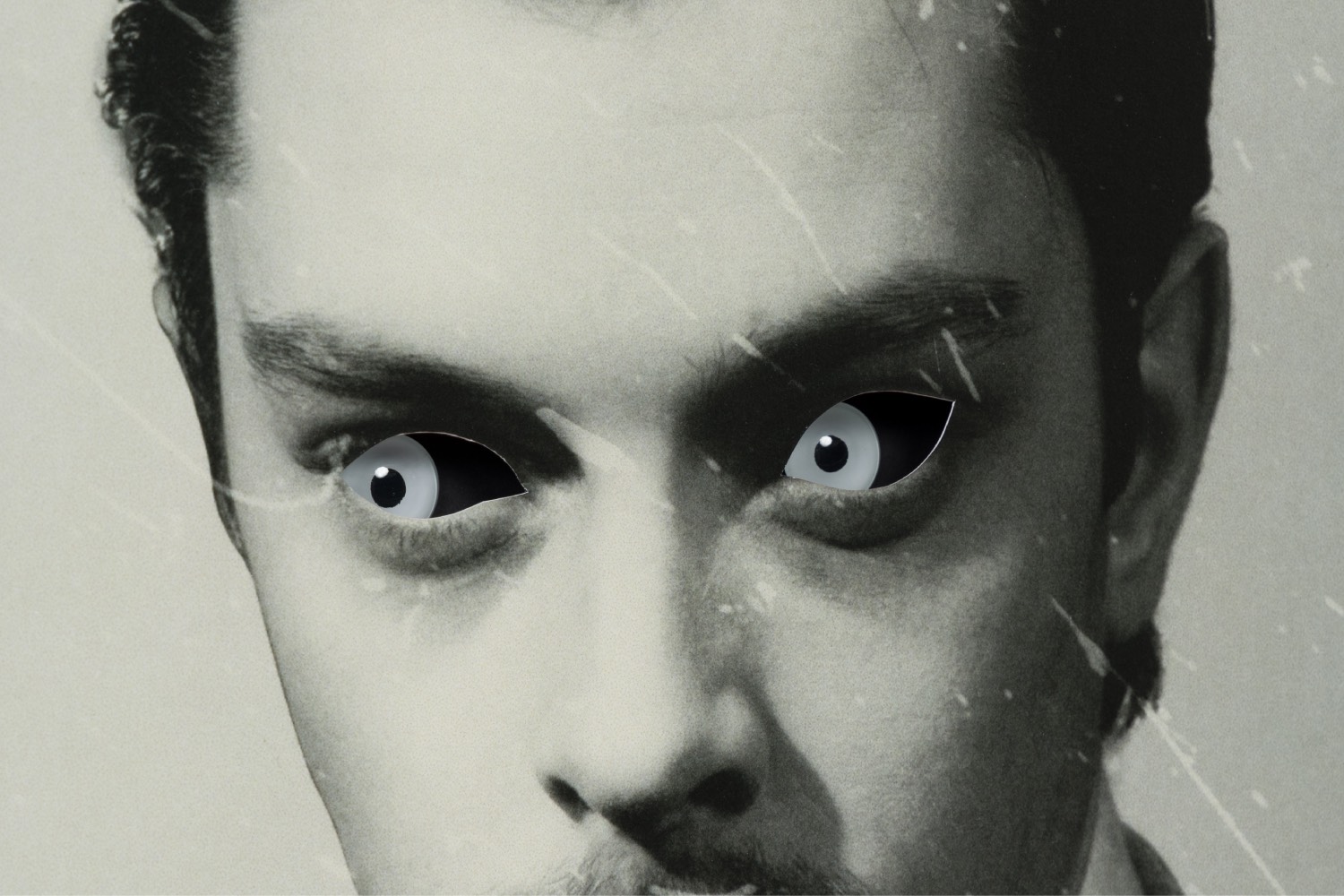

When I talk to Megan Plunkett, she’s driving across the American West. I imagine her in cheap motels, greasy spoon diners, gas stations. I imagine her having that languid feeling that comes from being on the road for hours, staring ahead, thinking about the strange vastness of the world. She sends me pictures from Roswell, New Mexico, the town famous as the site of an alleged 1947 UFO crash. Metallic and rubber debris was discovered in an army airfield that conspiracy theorists claim could only have come from extraterrestrial life. In the context of such conspiracies, the photograph becomes the most appealing form of truth. The evidence presented on film takes on the authority of undeniable fact. Plunkett’s photographic work pushes against this authority of the image, often indulging the strange in-between of fact and fiction. The work becomes more about the impulse on the part of the conspiracy theorist who imbues images with their power. I imagine in Roswell they sell T-shirts that say “I want to believe.” She’s been drawn to UFOs and their photography for their ability to create “an image problem” — a problem she says is great for artists because it’s about possibilities.

Gracie Hadland: When did you get interested in UFOs? Has this always been a fascination of yours? I like this idea that UFOs are great for artists because of some kind of impossibility.

Megan Plunkett: I’ve always been into UFOs for as long as I can remember. I’ve always been interested in stuff that is unexplainable. The first time I showed UFOs was at Sweetwater in Berlin in 2022. I’m doing a two-person show in the fall with John Divola in Los Angeles. He’s showing his “X–Files” series from the ’90s and I’m showing my UFO photos. I think I’m interested in them because they create this image problem that is related to the challenge of impossible thinking. It’s just another object in so many ways, but also, what even is “it”? It could be anything or nothing, we truly don’t know. I tend to like to work reductively, and it suits me in that way because it’s just light and reflection. So, finding weirdo avenues that I can push the work through. There’s also this relationship to the image as an object that I’m still trying to articulate. And, of course, it has this weird and specific pop- cultural aesthetic history of its own, which becomes our internalized cues and expectations.

GH You said you found some good alien merch that you want to make something out of. What is it?

MP Oh, I took a picture of my favorite thing that I bought in Roswell to show you: it’s an alien basketball! I think I might try to make a scarecrow out of it. I’ve been wanting to make one for a while, and when I saw the basketball, I thought, “Oh, maybe I just found my scarecrow?”

GH Why do you want to make a scarecrow?

MP It’s an object that’s been on my list for a while; it ticks the boxes

of what I’m interested in. A scarecrow is this homemade thing that’s cheap and weird. And it’s also an anthropomorphic object. I love that it’s nonhuman but is based on human objects at the same time. I’ve never shot images of real people, but I see the scarecrow as a sort of portraiture anyway.

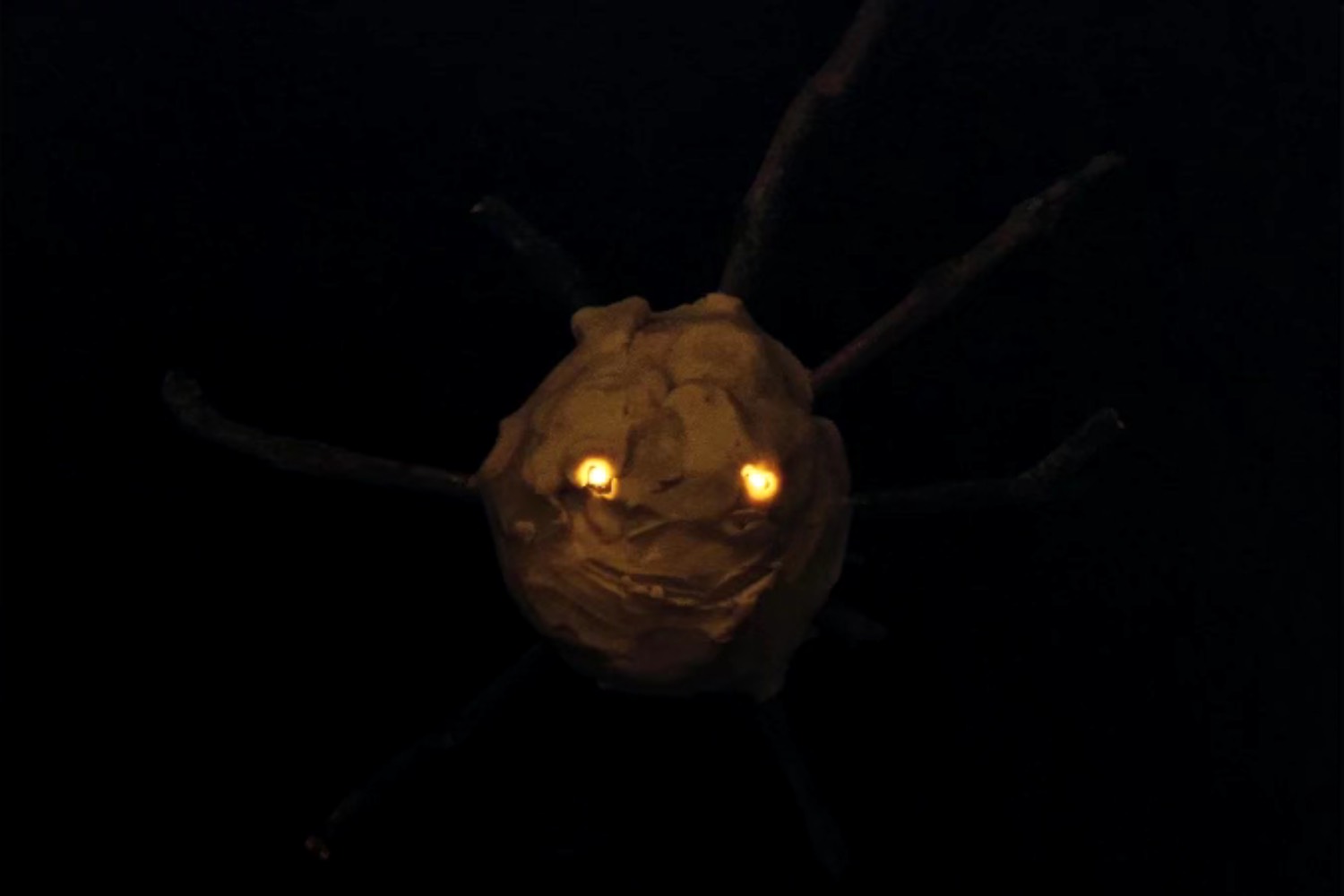

GH Can you tell me about the sun portraits and how they relate to this other work of cans and UFOs? I like this image of this object/creature with the beady eyes. What is it?

MP It’s a little sun. It’s called The Answer Man (2023). I’ve been interested in anthropomorphic cosmo stuff for a while; it’s an object world that I like. It’s a little crafty and homemade, and a little spooky too. I made it myself in the fall, while I was working with molds of some old brooches that were suns. It was like a little piece of foam that has putty over it and sticks. I have these little lights I use all the time in the studio to make eyes or just cast small shadows that are very tiny — they’re like little balls maybe like a quarter inch in diameter, and they just come in all colors. I like these controlled light conditions. So, here, I just used them as eyes.

GH Sometimes you manipulate images afterward, but also a lot of the ways you alter your subjects are just with light. Most of these cans are just shot with controlled lighting. What is it about the cans that you were drawn to?

MP I did this CSI training at UC Riverside where I did this photo forensic course. It was great for me, but I also realized how much I loved photographing glass and cans. I think I started really honing in on certain ways that I was relating to the object in terms of the image I was trying to get out of them. The photos of cans started around the same time. When I shot the first cans I did no manipulation or editing. The photos are all digital: I just shoot them with lights. The first ones were those alien cans, which were an actual Budweiser promotional product for Storm Area 51, an event that never happened. They made these weird cans that were black with aliens on them. I went and bought a bunch of them, and I started using them when I was doing my exercises about photographing fingerprints for the CSI program. And then it just kind of gathered. I feel like maybe that was the first moment when the seal was lifted. Since then, I’ve shot objects that are props, or off-branded things. You know, sometimes they’ll make fake brands just for movies. Like this fake beer called American Colonial. I’ve shot that one a couple of times.

GH The CSI training makes a lot of sense in relation to your practice because of this interest in different uses of photography. This crossover between art photography and other fields or types of thinking. Because these are real images, right? They’re often not what they claim to be. Or maybe they are?

MP In forensic imaging, there’s a term called a “matching image,” which is really interesting to me. I think about a lot of stuff that I do being like that. It’s a sort of faked photo to create the narrative of what happened for someone on the outside. An example of a matching image in forensic terms would be, like, you find a broken hammer at a crime scene, and you photograph the two pieces at the crime scene. But you also take it back to the lab and then photograph it with scales in a proper setup with a ruler, showing it together. Then you could show these in a courtroom and be like, “image one, image two,” and without having to defend it, the jury would say, “Oh, my God, that was one thing, and it broke at the crime.” It’s this very flat-footed kind of faked yet also legal fake of an event. It’s about the way an image ricochets back and forth.

GH It’s about the relationship with the viewer, persuading them of something. It relates to UFO imagery. These real images exist, but they’re often not of the thing that they claim to be.

MP Yes, it’s a way to very clearly establish a narrative for people. The matching image idea is about something that happened, but it’s usually just related to an object. It’s like, “the window broke,” and then creating and showing images so that a jury is like, “Oh, yeah, the window did break.” But I guess it’s not really manipulation. It’s this weird, slowed down version. I think it’s also interesting how you arrive at some idea through accumulation of images. They just pile up — some are fake and some are real — and you’re in this weird nether zone when you’re in the soup of it. Then through each other they gain some power. It’s like the image gains some ennui just by its relationships with the other.