It took Alice Channer a while to go to art school and start her BA. Part of the reason was economic: by entering university in her late twenties, in 2003, Channer was able to save enough money to put herself through Goldsmiths. But the other major barrier was authorship.

An author, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, is the creator of a particular, original work. Authorship, by involving an authentic creative voice, implies ownership.

Under neoliberalism, however, authenticity and authorship translate into ownership of modes of operation. Although these two separate operations — the artistic and the economic — cannot be reduced to one another, they both establish an economic and financial trajectory.

As Channer told me, she didn’t see herself as an author, because she wasn’t interested in having a “self.” She needed alternative creative models. Was it possible — or even illuminating — to work in survival mode? All of the prominent artistic models she was aware of at the time seemed to require an assertive originator — a foundational and authentic artist’s body and self.

Channer has spoken about the importance of the free party and rave scene of the 1990s, which she experienced on the southeast UK coast. For a while, this scene provided a potent, collective alternative to neoliberalism. It fostered an understanding of a complex kind of authorship, one in which each work contains multiple authors that are constantly renegotiated.

In contrast to the terminology that was widespread at the time of her artistic upbringing, one can offer a set of nonbinary notions: instead of “natural,” don’t think about the synthetic, try “multispecies.” Instead of “vertical” (forget “horizontal”), try “expandable” or “disseminative.” Instead of “foundational,” try “peripheral.” “Solid” can become “flexible” or “malleable.” “His” can become “theirs.” Most importantly, “original” can be “exilic” (rather than a fake, a copy, or a kind of binary duplication, the exiled is that which is both removed from and belonging to in a non-immanent manner). Instead of “normative,” try “deviational.” The “artist” can be replaced by a group of “agencies.” The “singular” can be thought of as the “eventful.” “White” turns “colorful” and the “gendered” is “queer.”

Departing from these definitions, each of Channer’s works adds visibility to the conditions of its polyphonic production. This slower way of working goes against the manufacturing logic of the market. Her works are composed mainly of natural objects and representations of natural elements (e.g., mussel shells, fingers, rocks). She “transforms them through encounter,” 1 a process that encourages dual contamination while focusing on mutual assistance. As someone with an injured leg might rely on crutches, so too do the artist-agents who act in the work rely on assistance from other agents. This happens in a massive, multispecies process, usually involving professional manufacturing plants that are typically not related to art production, such as can be found in the chemical industry.

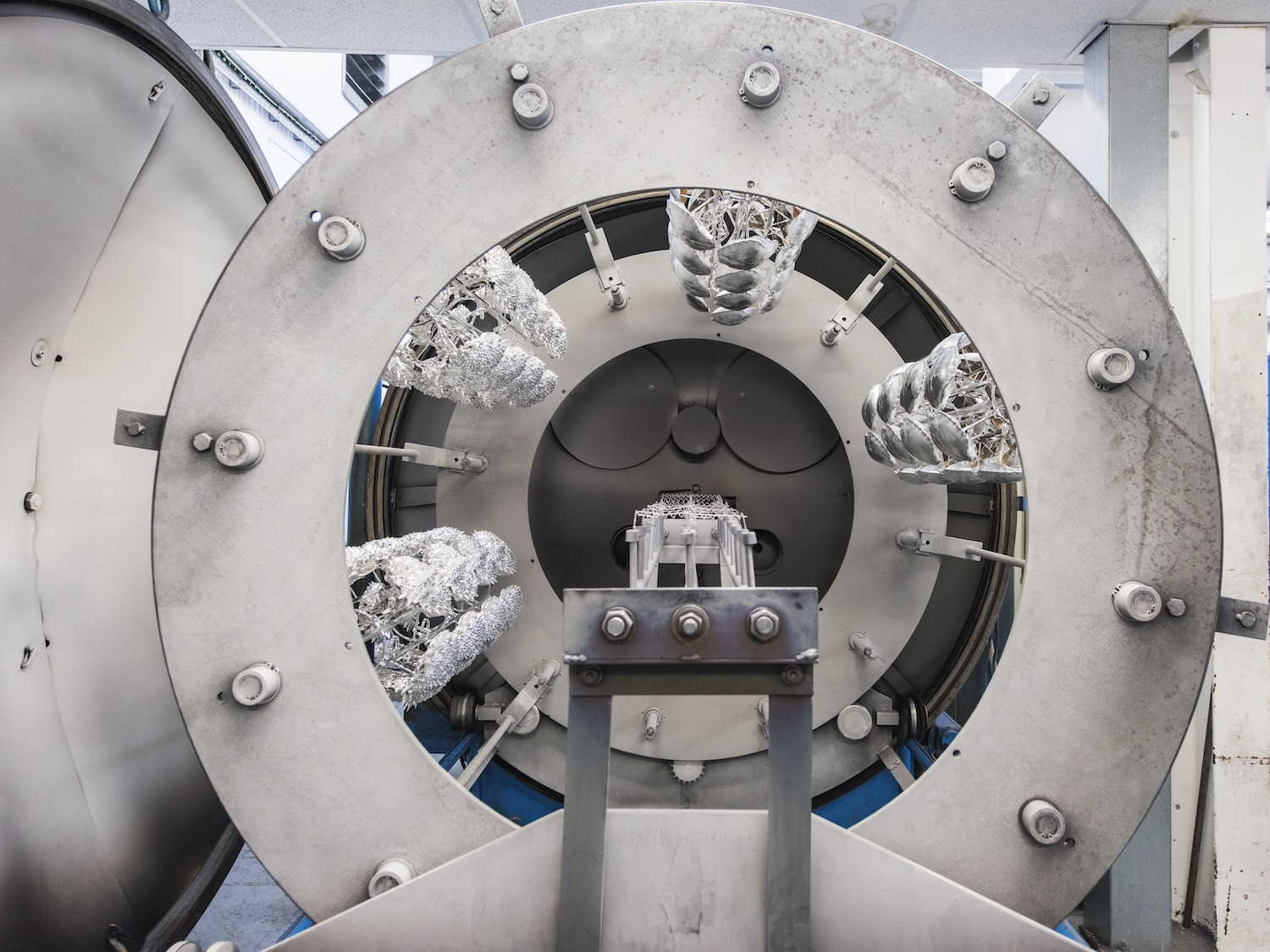

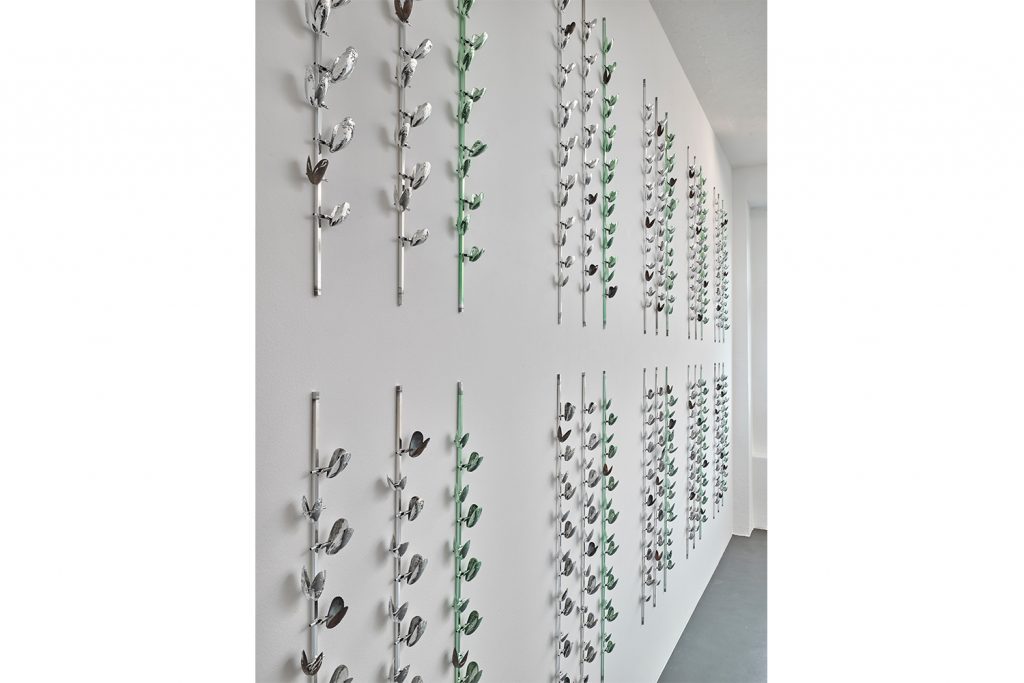

For example, in Mechanoreceptor, Icicles (red, red) (triple spring, triple strip) (2018), Channer created a cast of her right index finger. After making a 3-D scan of the cast, Channer stretched the scan and created a 3-D print of the image. She then cast the print in aluminum, dipped the fingers in liquid PVC, and, with the help of a metal manufacturing company, created a support structure that could hold the fingers in the dipping process. This structure, which is incorporated into the final object, consists of frames with a customized strip and spring attachments for the 210 aluminum fingers. In the object, we see standard industrial accouterments, which were customized to hold the fingers in the machine. These adjustments were necessary to enable the dipping process, to make it safe (it’s a toxic environment), and to create the object as such, since the support structure is not usually made to hold “fingers.”

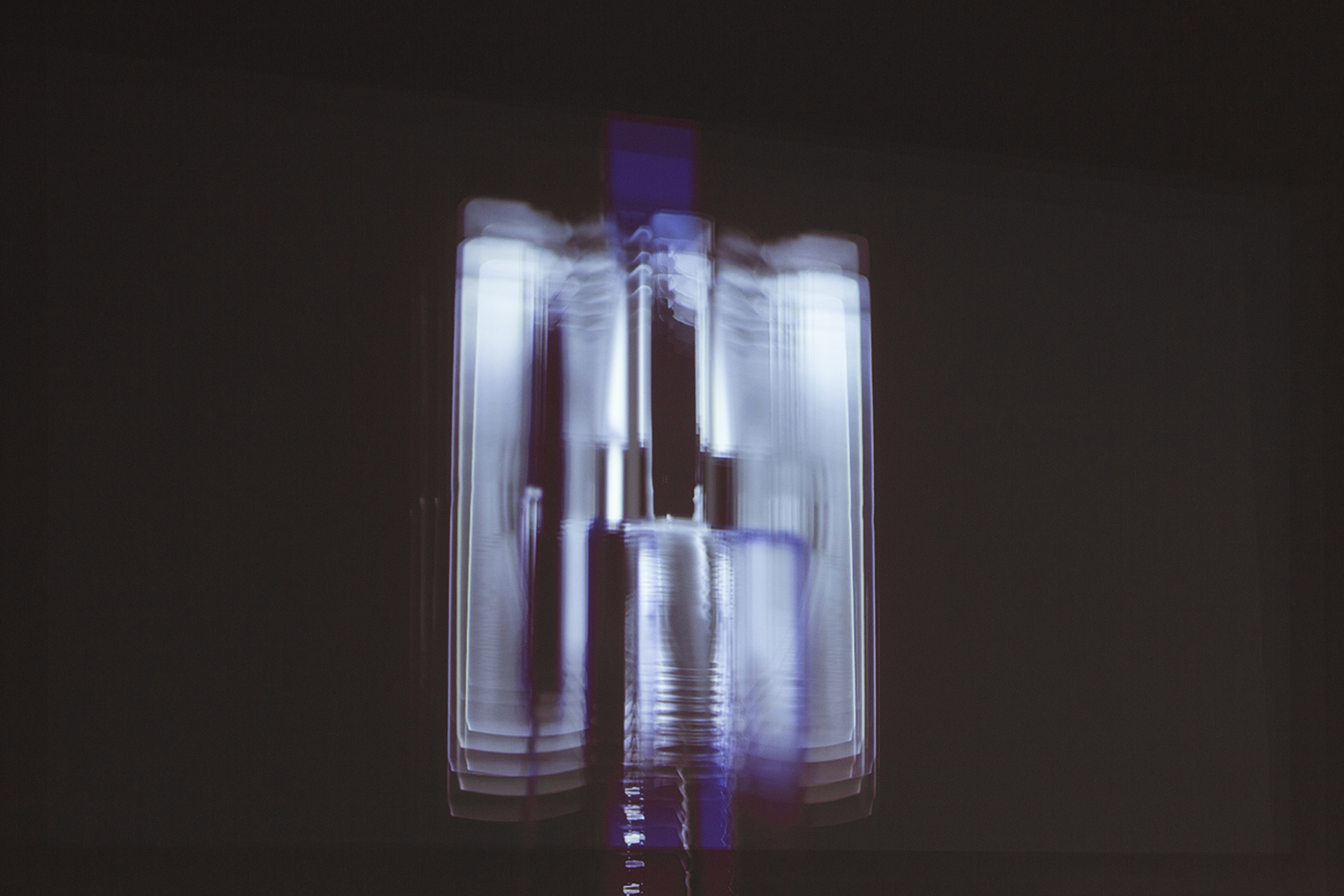

Similarly, in other works “by” Channer, both the machine and the human directing it leave significant traces: a production tool, a support structure, or a carousel become integral parts of the final work.

These inclusions, resulting from the nature of a rhythmic and mechanistic industrial production, constitute the new object. The human creator is included in them by her presence or absence. This creator is not necessarily the artist. Rather, it is the laborer, the factory worker who works on that particular production line. She will not be privileged over the other actors contributing to the formation of the work.

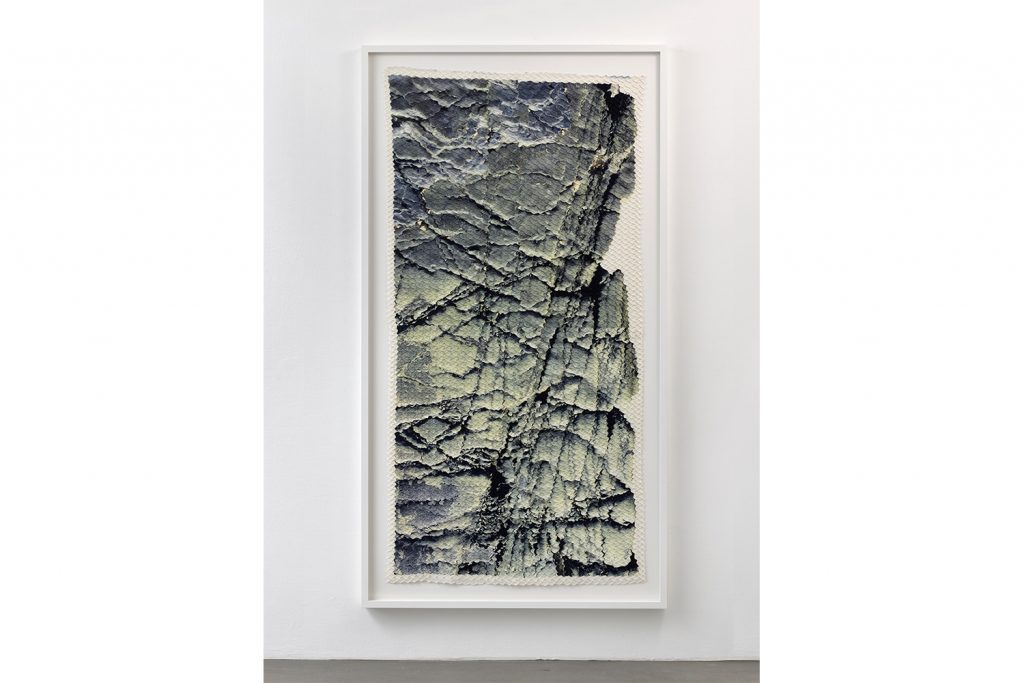

Looking at her pleated, couture-like works, we find a line of printed text that contains various details about the work’s lack of originality. It reads: “THEIR DOUBLE CREPE: [the fabric type], Alice Channer Studio: [the name of the client or customer], 11461: 1539793470: -Alice-Channer-Own-Fabric-HCDC-R500-Printer-136-x-290-cm-17-10-18: [name of the file to be printed] 2.9M: [amount of fabric that will be printed] R500DEC16: BPC%%FINISH%%.” This apparently menial and routinely informative line adorns Channer’s glamorous works, and as such undermines the unique value and nature of the work. This inclusion emphasizes the lack of a single, authentic creator and enhances the work’s authorial polyphony. The “signature” at the bottom of every print “by” Channer is a key to how she imagines authorship and its operations: as the mark of multiple, equal authors (e.g., a machine or several machine operators, an incorporated company, a client, an artist). Channer never knows what color the signature will be. Typically, in other contexts, this printed line of information would be cut from the fabric. Sections of this signature are always slightly different in Channer’s work, and since the signature does not belong to her, only parts of it are legible to her.

These objects, pulled out of industrial and postindustrial production processes, convey glamour. Glamour, according to Channer, rules out authenticity. It acts as a false wish, pumped by market forces that transform us into goods.

The glamour, which can manifest itself in small tweaks — for example, the glittering, electropolished stainless steel in Mechanoreceptor, Icicles (red, red) (triple spring, triple strip) (2018), or the mirrored aluminum surfaces of the many crab and mussel shells in the sculptures Planetary System (Kolzer DGK63”) (2019), Crustacean Satellites (2018), and Linear Bivalves (2018) — smooths out everything. It’s a kind of weaponized glamour that flattens any request for an authenticated object.

Glamour, then, irons things over, makes them look simple while disguising their complexity. It has a particular relationship to surface and depth (a quote from an unknown source tells us, “Glamour is not easy or straightforward. It is a hard, shiny surface. Things slide off it; it deflects and reflects”). Metals, which are found in abundance in Channer’s work, are shiny partly because of the free electron that moves around in each atom. The idea that a shiny, glamorous surface is a consequence of the substance of a metal on an atomic level is seductive: these surfaces are fundamentally energetic rather than static. “It is metal, bursting with a life, that gives rise to the prodigious idea of nonorganic life.” 2 Jane Bennett amplifies this idea further by claiming that the structure of metal is full of holes, mainly due to the shifting atoms recomposing a piece of metal. These molecules constantly travel to reformulate different tools, instruments, and machines. Bennett reminds us that metal is defined by its self-transformations and by its ability to connect, reshape, and reformulate other objects. 3 In this sense, metal accumulates in Channer’s work to become a complex instigator of glamour. It betrays essentialist notions of authorship and of singular or foundational origins — in short, it undercuts authenticity.

That is not to say that Channer’s work in inauthentic. Since we’re trying to leap out of binary discourse, we can call her work unique. It is unique because of its modes of operation and production, which make it a site of communal actions. Each action or actor originated in its removal, in its random exile.

In her seminal book The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing explains the idea of transformation through encounter. Persons and things, uprooted by the forces of twenty-first-century globalization, are transformed into atomized, mobile assets. This removal into another utility-based, profit-generated framework sends multispecies things and beings into exile. To survive, Tsing suggests focusing on “liveable collaborations” 4 : mutual work and contamination across and within species and geographies. This kind of collaboration results from displacement, owing to imperialism and financially driven extermination.

Exilic beings do not “privilege origin” of any sort. 5 Channer brings together often-contradictory ingredients to form a body in which the exiled act in common, in one place. It is almost as though she gathers banished elements and puts them back together in such a way that allows them to find common ground.

In this sense, the concept of critique by Walter Benjamin becomes useful. Like Benjamin, Tsing proposes an alliance between testimony and survival that involves a unique reconsideration of both temporality and spatiality. Benjamin’s aims are not to explicate what constitutes an experience per se. Nor does he seek to situate conceptual unity, essence, or objectivity in lived experience. Rather, Benjamin’s project targets and undermines the conceptual determination of experience and is suspicious toward its objectifying language and its essentialism, which so rapidly transforms discourse into a jargon of authenticity.

The question of “belonging” to a geographically and historically determined site invokes the countless detours, contours, and forms of expropriation and abstraction that are specific to exilic experience. In Channer’s practice, the question of “origin” leads to exile; Channer reforms the size and ratio of the interior-exterior relations we ordinarily have with the world. They become alienated and glamorous, but also intimate and multispecies.